Designer-turned-fighter struggled with his sexuality after fatal fight.

July 24 2013 11:37 AM EST

May 26 2023 1:40 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

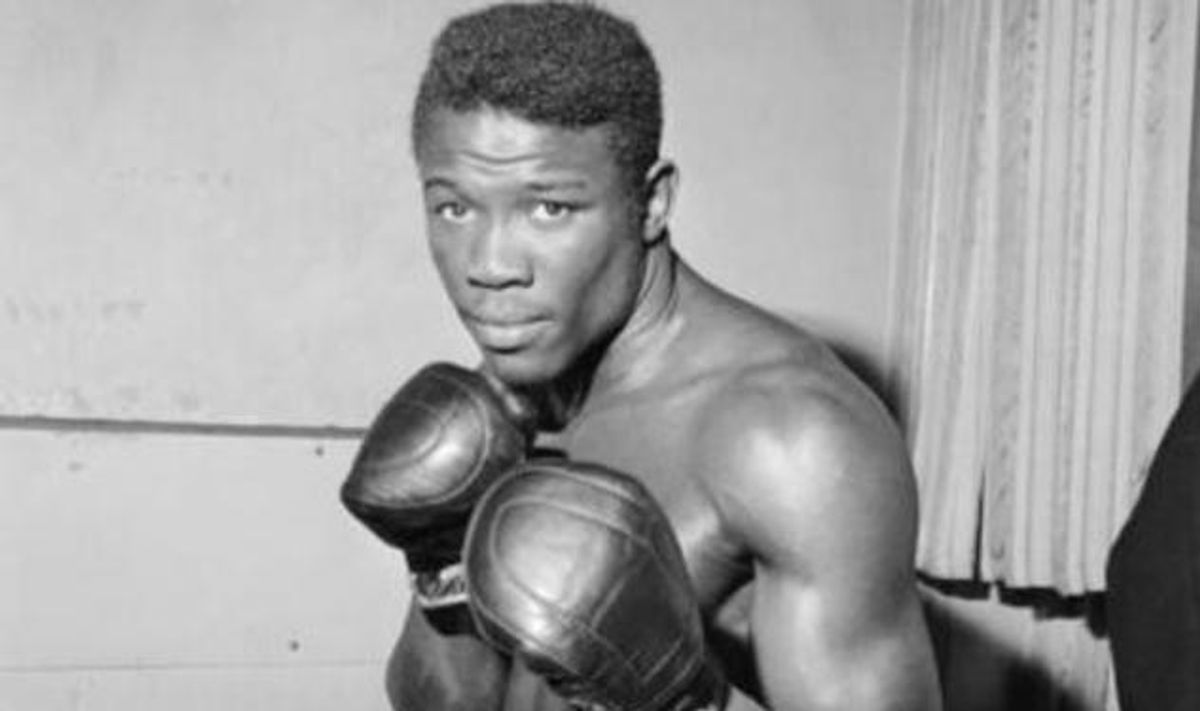

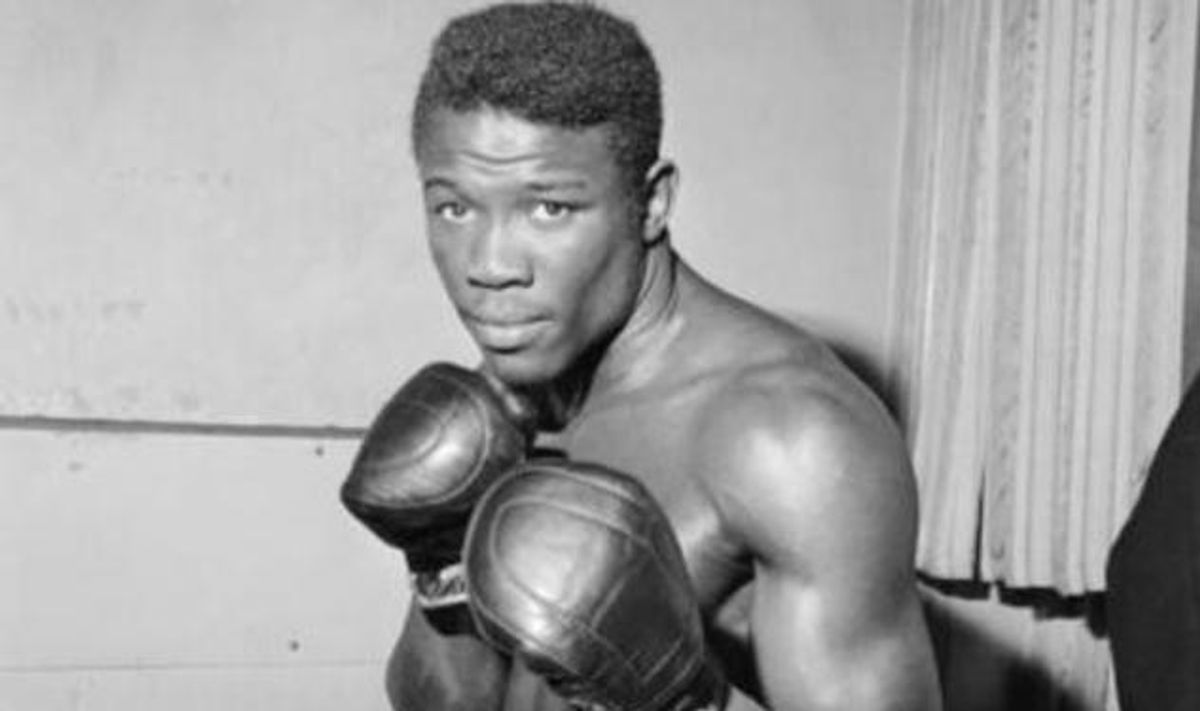

I knew nothing about Emile Griffith until recently. I don't follow sports and somehow over the years I missed the story of the designer-turned boxer who, only a few hours after being called a maricon (faggot) by a rival, delivered the blows that would lead to that rival's death. And I was too young to take note in 1992, when Griffith was severely beaten after leaving a gay bar in New York City, nor did I read the 2005 Sports Illustrated article in which the fighter, long hounded by gay rumors, admitted, "I will dance with anybody. I've chased men and women. I like men and women both..."

I didn't know any of this until I read The New York Times' riveting obituary of Griffith, who died yesterday at age 75.

Griffith, born in 1938 in the Virgin Islands but raised primarily by relatives in New York City, started his working life as a hat designer and didn't turn toward boxing until the late 1950s, when his employer, a former boxer himself, suggested he get in the ring. Griffith did and in 1958 he went pro, rapidly winning welterweight championships and becoming one of the most talked about athletes in the world.

Then, on March 24, 1962, at the weigh in for their third fight, Griffith's rival, Benny "Kid" Paret, called him maricon in front of everyone. Some reports say Griffith lunged at Paret right then and there, but in the end the fight unfolded in the ring, where, at the start of the 12th round, Griffith dealt seventeen punches in 5 seconds. Paret went down, knocked out cold. When he was taken to the hospital, Griffith reportedly said, "I pray to God -- I say from my heart -- he's alright." Paret wasn't alright, though. He was in a coma and ten days later he died from blood clots in his brain.

Griffith returned to the ring after that incident and though he won a few titles, he lost more often and in 1977 he retired. He would later tell Sports Illustrated, "After Paret, I never wanted to hurt a guy again. I was so scared to hit someone, I was always holding back." Griffith was also holding back on his sexuality and it wouldn't be until much later that he began peeking out of the closet. "I don't know what I am," Griffith, who was once married to a woman, told Sports Illustrated in 2005. "I love men and women the same, but if you ask me which is better ... I like women."

But New York Times columnist Bob Herbert, who spoke with Griffith that same year, said that though Griffith told him he wasn't gay, the fighter appeared "agonized" over his denial.

"I asked Mr. Griffith if he was gay, and he told me no. But he looked as if he wanted to say more. He told me he had struggled his entire life with his sexuality, and agonized over what he could say about it. He said he knew it was impossible in the early 1960's for an athlete in an ultramacho sport like boxing to say, 'Oh, yeah, I'm gay.'

But after all these years, he wanted to tell the truth. He'd had relations, he said, with men and women. He no longer wanted to hide."

In that same article, Herbert says Griffith's explanation for the Paret fight was "I got tired of people calling me faggot."

As he hoped to come out of his shell, Griffith's health, in decline since that 1992 attack, kept him homebound most of the time, cared for by his adopted son and companion, Luis Griffith, and helped steal his memories, which, for a man haunted by another's death, may have been a blessing in disguise.

Griffith's life story inspired Terence Blanchard to write Champion, an opera that just premiered last month in St. Louis. Here's what the Times said about it:

"The comic interludes are in contrast to the many poignant elements of the narrative, like Emile's abandonment of his wife (expressively sung by Chabrelle Williams), his confusion about his sexuality, and the dramatic duet between Emile and Benny Paret (an effective Victor Ryan Robertson), seen here in a coma on his death bed after the match.

George Manahan conducted the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra in a confident performance of the jazz-inflected score, woven through with bluesy harmonies and Afro-Caribbean beats. The music at times sounded thin and the dramatic pace sometimes flagged, but over all the score's cinematic flow aptly complemented the action on stage."

And here's footage of Griffith, his friends and family discussing his life, his career, and Paret's death:

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays