Could Andrew Haigh’s new HBO dramedy, Looking, be that rare thing — a gay TV show about the rest of us?

January 14 2014 8:27 AM EST

May 26 2023 1:54 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Could Andrew Haigh’s new HBO dramedy, Looking, be that rare thing — a gay TV show about the rest of us?

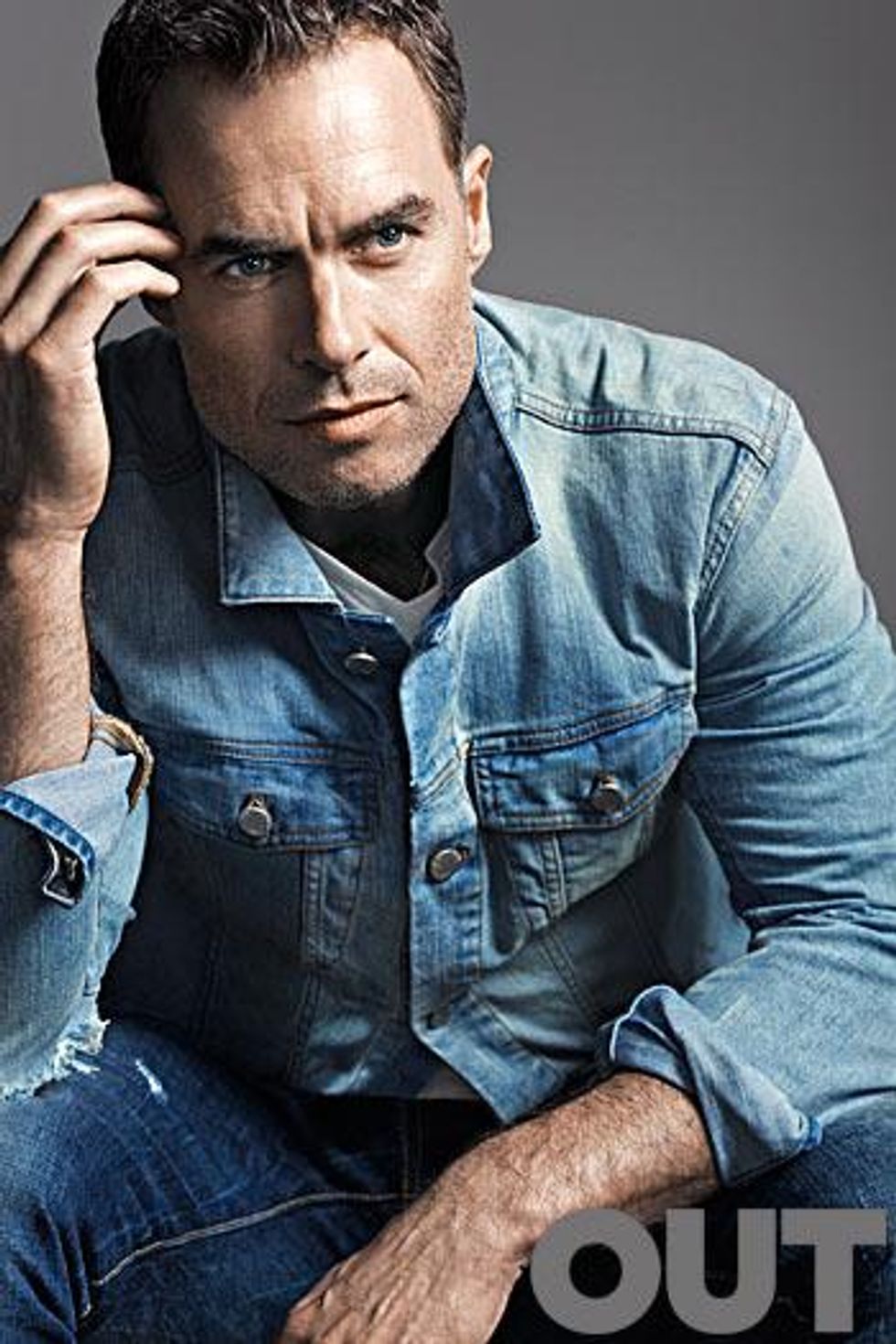

Pictured: Jonathan Groff | Photography by Nino Munoz

For nearly a year after the premiere of Girls, when the words "Lena Dunham" began to crowd out all other conversation topics, thousands of gay men in New York City and Los Angeles began walking around with the same half-written treatment for a television pilot in the back of their heads. It stood to reason that someone would get rich and famous by making a gay version of Girls. Last May, HBO announced that person would be Andrew Haigh, the little-known director of the critically acclaimed 2011 gay indie-romance film Weekend.

Finally pulling the trigger on an idea that had been batted around for years, HBO ordered eight episodes of a dramedy about a group of gay friends living in San Francisco. The show would air on Sunday evenings, directly after Girls. Contrary to expectations, it would not be called Fags, Queers, 'Mos, Gays, or Boys; in a nod, perhaps, to straight viewers' relentless fascination with the lingo and mechanics of gay hook-up apps, the series would be called Looking, a word that usually appears on Grindr followed by a question mark. To those familiar with Weekend, which chronicles 48 hours in the life of a mismatched gay couple in the dreary East Midlands city of Nottingham (a city most famous for a nasty sheriff from the Middle Ages, sometimes depicted as an animated gray wolf), it was clear that the characters in Looking would be, in the words of the show's adorable star, Jonathan Groff, looking "for love" instead of "for right now."

For legions of would-be project developers, a gay-themed HBO comedy has been a holy grail for decades. Way back in 1982, the network acquired the rights to Armistead Maupin's Tales of the City -- a cycle of novels set in late-'70s San Francisco -- with the hope of adapting it into a weekly sitcom. The concept went into pre-production, but executives eventually determined audiences would not accept a show celebrating gay sex in the face of the worsening AIDS crisis (the novels were eventually turned into a miniseries by Britain's Channel 4 and aired contentiously on PBS). Then Queer as Folk, based on another U.K. series, premiered on Showtime in 2000, proving that a gay sex drama could attract viewers somewhere on the raunchy fringes of premium cable.

BIG GAY TV TIMELINE: HOW THE EVOLUTION WAS TELEVISED

HBO, though, was in a class by itself. It had courted major controversy -- and major ratings -- by launching Sex and City in 1998, a show based on the column by the New York Observer's Candace Bushnell. The rap against Sex and the City, which stirred passions even as it upended the culture, was that it was already deeply, monstrously "gay." Summing up a view popular among concerned mothers, the critic Lee Siegel wrote in the New Republic that Sex in the City made a mockery of femininity by portraying women as cock-obsessed sociopaths. "Running through Sex and the City," Siegel scolded, is "a manifesto for a certain kind of raw, rough, promiscuous, anonymous gay male sex." Siegel's complaint boiled down to a single observation: "None of these women is hurt by sex." Therein lied the show's immorality.

It's difficult to predict what mothers will think of Looking, whose earnest, struggling characters share little in common with Carrie, Charlotte, Samantha, or Miranda. Instead of taking place in New York or Los Angeles, the show is shot in sleepy San Francisco, a city with a storied gay past and a booming high-tech present, but which hasn't hosted a major TV show in nearly a decade.

For Groff, who first visited the city two years ago, San Francisco feels like "the gay Oz." He says he was particularly struck by the legend that San Francisco became a gay haven for sailors returning from the Pacific after World War II: "It was the last port of call for all the guys in the Navy, and the ones who were gay just stayed there because they didn't want to go back to their lives." Groff adds that the show's three-month shoot, which took the characters to well-known San Francisco haunts like the Stud, the Cafe, and El Rio, was like a dream. "The street where I was staying smelled like jasmine," he says. "I rode my bike every day to set. I was in heaven."

For Haigh, Looking's director and co-executive producer, making sure the show was actually shot in San Francisco was his first order of business. "When I came on board," he says, "it was still unclear whether we'd shoot in L.A. or San Francisco -- everyone always says it's easier to shoot in L.A. -- but for me, it was like, 'We have to shoot in San Francisco. It needs to be about that city.' " Haigh also made sure the crew was drawn from locals. Like Groff, he speaks about the city in metaphysical terms: "Maybe it's the trams -- there's a melancholy to it. Fog coming in. Something wistful."

At left: Frankie J. Alvarez

Looking follows three gay friends living in the Mission-Castro district as they navigate relationships, careers, and friendships. Patrick, 29, played by Groff, is an affable video game designer with sexual hang-ups. His slightly older roommate, Augustin, played by Frankie J. Alvarez, is an artist's assistant who hasn't made work in years. Australian actor Murray Bartlett plays Dom, their mutual friend, a well-built waiter edging on 40 who has dreams of opening his own restaurant ("Dom has coasted by on his looks," says Bartlett, whose last major gig was on CBS's daytime soap opera Guiding Light. "He's at a point where he wants more depth in his life"). None is an heir, a genius, or a supermodel. Each has a lot of feelings. Unlike the stars of Girls, the men on Looking are not the emperor's children -- they don't hail from dynasties of artists, musicians, playwrights, or prime-time news anchors. They aren't trying to date celebrities or become the voices of their generation. In part, they're too old.

"Our show is less about people at the beginning in their twenties figuring out who they are," says Groff, "and more about people stepping into their lives in their thirties and forties and finding their place in the world."

Haigh says he didn't want "hyper-successful" characters, betraying an interest in ordinary people that is more common on television in the U.K. than in the United States, where viewers tend to favor aspirational plotlines. "All the characters are from different socioeconomic backgrounds, different ethnicities -- that can happen a lot more readily in the gay community," Haigh says. "What you connect to initially is your sexuality, not your age or where you've been to school." The characters in Looking, he says, are "not aspiring to be rich. They're not aspiring to have lots of sex. They're aspiring to have happier lives, more fulfilled lives."

In comparison to Girls, says Alvarez, who was doing regional theater in Louisville when he mailed in his audition tape, "our show is sweeter."

In the opening scenes of the first episode of Queer as Folk, the groundbreakingly graphic Showtime series about a group of gay friends in Pittsburgh, a tall, virile advertising executive named Brian goes to a club, picks up a blond twink still in high school, takes him home, and lingually deflowers his virgin ass. "I remember watching it -- I wasn't even out then," Haigh says. "I was at a friend's house and it came on and it was, like, so exciting. I was like, 'This is on television?' "

Though 10 years Haigh's junior, Groff -- who was roughly the same age as Justin, the rimmed twink from the QAF series premiere, when it aired -- had a similar experience. "I was in high school," he says. "I remember I was visiting people who were in college and we went to a party and it was on TV. The scene I saw was somebody fucking somebody in a steam room. I remember thinking, Oh my god! It was very salacious to me. I knew I was gay at the time, but I was still in school and totally in the closet. It was like 'Whoaaa, that's a lot. That's a lot to see.' "

Looking also begins with a graphic sexual encounter, but without the disco-thumping atmospherics that propelled Queer as Folk. "The very first scene of the pilot is me going out to the woods to get a hand job," says Groff, simply but accurately summarizing a sequence in which the innocent Patrick goes cruising for the first time in a San Francisco park. The scene starts with a close-up of Patrick's fresh, wonderstruck face -- he's like a cuter, muscle-enhanced Michael Cera -- peeking through lush foliage. The camera then turns to a rugged older man, similarly wonderstruck, who reaches for Patrick's crotch. (Patrick's expression is sweet and somewhat fearful; on his graying counterpart, the same look comes off as lecherous and slightly demented.) The characters seem destined for a silent encounter in the bushes, but Patrick squanders the moment by first whispering awkward small talk, then attempting a kiss, and finally taking a call on his cell, which erupts with an explosive ringtone reminiscent of a Super Nintendo sound effect. In the next scene, we see him walking down a sidewalk with Augustin and Dom, awkwardly reliving an awkward moment -- "It was a very, very small hand job, like two seconds long, and the guy who gave it to me was very hairy -- not even hipster hairy... like, gym-teacher hairy" -- as he endures the teasing of his more sexually experienced peers.

On most shows, if a character mangles an attempt at cruising, it's an occasion for uproarious slapstick. But Looking, whose hyperrealism borders on cinema verite, doesn't contain "jokes." As Haigh explains, "It's slice of life. Instead of 'Here's a joke, here's a joke,' you're watching these people's lives. Sometimes it's funny; sometimes it's not so funny." Whereas most comedies use awkwardness as an engine of humor, embarrassing a character to get a laugh, in Haigh's hands awkwardness becomes relatable, even erotic. Patrick's fumbling is not simply endearing -- it's what makes him an object of desire.

"For me it's not about, awkwardness, really," Haigh says. "It's that real life is... awkward, I suppose," which sounds like an appropriately awkward response. "It's the difference between people, the lack of clarity, all those things that make people gently butt up against each other -- that's what's fascinating and sexy. It's not about big conflict or high drama; it's about all those little things in life that make us embarrassed or uncomfortable." Looking does not rely on glittering wit, slick fashion, or edgy transcendence to power its storyline. It relies on the joy of recognition that sometimes accompanies viewing a well-calibrated reproduction of daily life.

As with Haigh's earlier work, the show has no score. "I told HBO in our first meeting that I don't like having a score," he says. "There can be music, but it has to be playing in the scene. I wanted a naturalistic approach. I also didn't want it to be super cutty -- I wanted to do longer takes." Looking is drenched in blues -- the whole series looks as if it's been run through the Nashville Instagram filter -- a palette appropriate to its slow-moving, somewhat somber lilt.

The first time I saw Weekend, in the fall of 2011, I recoiled from its indie sensibility. This was not an art film, I huffed to friends, but artisanal cinema -- an orthodox translation of a sentimental format to a dismal gay context. The film was contemporary without being cutting-edge, slavishly beholden to a boring, now superseded ethic of authenticity, which made it a perfect sell for global Brooklyn's "artisanal everything" hipster apocalypse. I didn't see what the Chris New character -- attractive, funny, articulate -- saw in his larger, lumbering screenmate, played by Tom Cullen. At the time, I had recently moved to Chinatown from Fort Greene, where my artist friends and I used to make fun of the gay "beardos," Brooklyn professionals who had adopted Vice fashions without ever embracing a Vice lifestyle. Didn't these mumblers know that indie was over? That it was time to wear cheeky athletic wear, get high on ketamine, and watch The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills? There was, of course, a bitter edge to my denunciations. Happy people don't make fun of beardos.

SLIDESHOW: TOM CULLEN ON DOWNTON ABBEY

When I recently watched Weekend again, I found it much more affecting. Was it because I was two years older and almost out of my 20s? Was it because I had moved to Los Angeles, where people aren't interested in anger and elitism the way they are in New York? Had I developed a more generous propensity for love?

Watching the first minutes of Looking triggered all of my nervous defenses. The characters were boring, it seemed to me. They were terribly dressed (costumes were procured from vintage shops on the Lower Haight, Alvarez told me, which looked about right). They were recognizable as the type of earnest gays I would see out at bars singing along to bad music, the sort that aspire to domestic triviality and read as "straight-acting" not because they are macho but because they are so sensitive. Once I let my guard down, though, I warmed to the characters and became invested in what Haigh and his cast members each described as their "journeys." "I'm not interested in angry, bad people," Haigh says. "I like stories about nice people. They get left out sometimes."

Looking is a show that will be watched religiously by millions of gay and straight people around the world. Many of them will like and look forward to it. Others will dread it but watch anyway. "It's always hard when you make a show about gay people because you just cannot -- no matter how hard you try -- represent every gay person in the world," Haigh says. "Because there's so little out there, everyone wants it to reflect their own experiences. All you can do is focus on a set of characters and who they are."

The way you feel about Looking may well line up with how you feel about life in general. Do you like most people? Do you appreciate the everyday? You can be a perfect misanthrope and still love Sex and the City. Looking, like life, is more demanding, but even snobby viewers will likely rise to the challenge. After all, if you can't bring yourself to like a show starring Jonathan Groff, your quest may never end.

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays