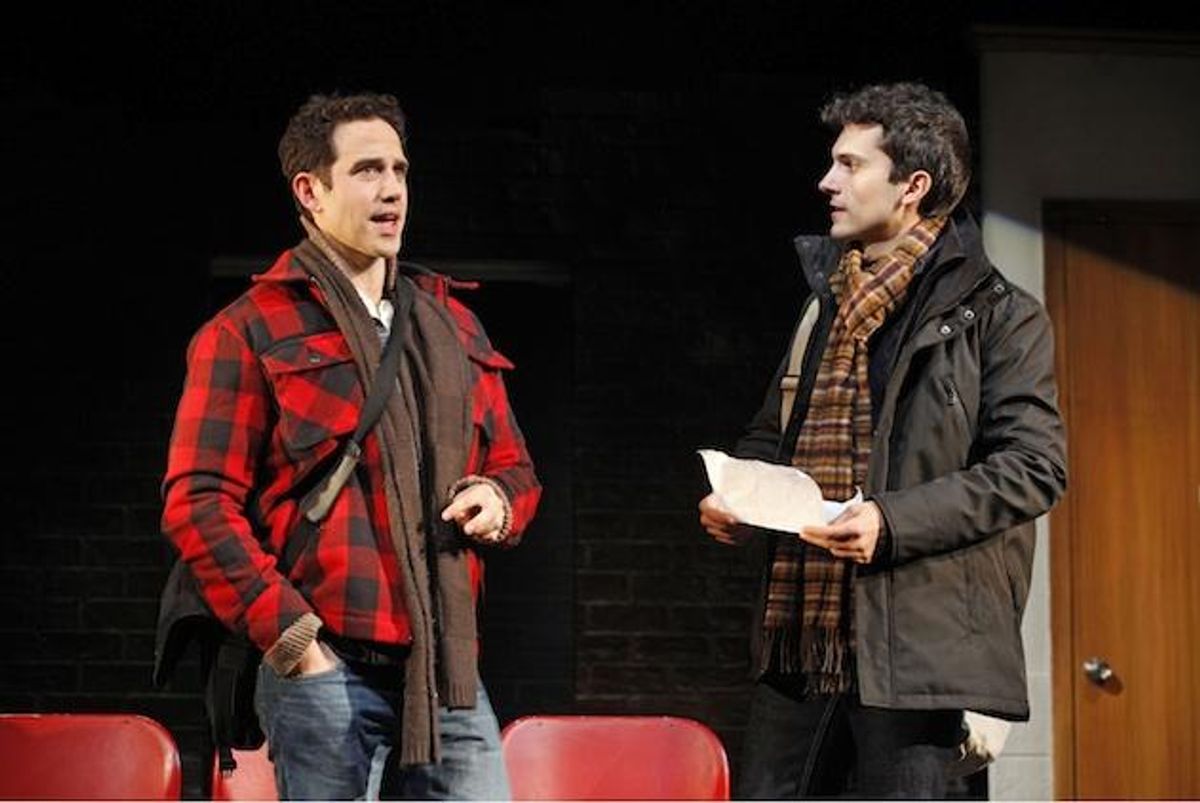

From left: Santino Fontana and Charles Socarides in Sons of the Prophet/Photo by Joan Marcus

The writing in Stephen Karam's play Sons of the Prophetis brilliant. Currently being produced by Roundabout at its Laura Pels Theatre Off-Broadway through January 1 (with rumors of a potential Broadway transfer), Prophet sneaks up on you with its layering of unusual characters, felt emotions, and collection of observed details. It's only afterward that you might think, Why did this playwright take so many risks by loading so much "difficult" material--having three gay characters, so many dark neuroses, and tragic (in the true sense of the word) circumstances--instead of crafting a simpler, more "marketable" play. Say, with one less gay brother--and fewer ailments. "I certainly had many, many people tell me I should change the gender or the sexuality of the characters," Karam admits, speaking about the play before a technical rehearsal for his other project, Dark Sisters, an opera by Nico Muhly for which he wrote the libretto.

His first professional length production was Speech & Debate in 2007, which also featured a believable young gay character (played by the actor out gay actor Gideon Glick in the Off-Broadway run). With two plays with such honest portrayals of gay men under his belt, we spoke to the playwright--and recent Out100 honoree--to see what it takes to stick to one's vision and create such incredible works of art.

So you have had two plays produced by Roundabout and have just received a commission for a third. That's significant! Tell me how it all happened.

It's my second commission, and my third Roundabout production. We brought the finished play to them and, from Speech and Debate they commissioned my next play, which was Sons of the Prophet. With Sons, of course this is on a bigger stage, I jut felt more pressure. It's a scarier prospect when you realize, I can't fill this theater with friends and family. I think they were so proud of the show, and they really liked the way audiences were reacting to it, so halfway through previews, I think they thought that, regardless of what critics thought, they were just really pleased and excited about the play that was being put on.

And then the critics loved it.

I get nervous talking about critics because... you know.

But you do read the reviews I assume?

In time. I can't read them the day or night of, nor can I read them the next day or two. If I get word from friends and family that they're not so good, I usually wait a month. I mean, they're going to be there forever. And almost anyone other than you can read the reviews and understand them. But I think it steals the focus from celebrating the work to suddenly to changing the focus to what other people think, instantly. And you cannot process what is being said; your mind dwells on anything negative. You do feel like it's someone is making fun of a relative or, like, my child. I realize you need a little bit of space before you can process it any right frame of mind.

One of the things that I'm curious about is that, while I was watching Sons of the Prophet, I suspected there was this gayness in it but it wasn't obvious and I was trying to figure it out. But I think a lot of the matinee audience, who weren't gay, they had no idea and were shocked when it suddenly came out.

Yeah, the subscribers were shocked. [laughs] Well, it's also playing with rules, this notion that, if your lead character is gay, you need to know from like the third sentence. I think there's this notion, even in dramaturgy discussions about the play--that he has to do something with his hand or talk about being with his boyfriend. I think, the only reason I could do something like that and let it come out at the end of the second is, by that point it's just someone who they know. During the matinees, you always hear someone say, "They're BOTH gay?" That's a line that's almost added in to every matinee performance.

But that's what I mean, it's a risk. It's not something you had to do.

The only reason I can do something like that is that I'm standing on the shoulders of a lot of brave writers who blazed a trail. Like Larry Kramer to Terence McNally, Tony Kushner, Craig Lucas. I just think the reality of our generation is that we all know someone who is "post-gay," who came out by just bringing their boyfriends home in middle school. I'm in my early thirties, and I know there are people who came out 18, 19, 20. It's a conscious choice to not shy away from what I know. It's also not to think about it too much. There are organizations like Exodus, but we've also come so far that we have kids who come out and it's a non-issue.

I think in this family, I sort of stacked the deck. I grew up across the street from the Duwahis (which is the name of family in Sons of the Prophet) and two of the girls who lived there were my role models and heroes growing up. They were seniors when I was a freshman; they were sisters and lesbians. So I think what was even riskier in getting the audience to accept was having two gay brothers and also having that be something that just is.

And there's an extended family that also seems able to cope and handle it.

Which is a reality for a lot of people. The love is so deep and unspoken that, although the uncle is both heavily prejucided, he would also do anything for either of his nephews. I think you sense that he's on their side--even when he's driving them both clinically insane. I think you sense that they're a functional family, in a way that I think gets overlooked because there is so much dysfunction going on in the family because of health issues and work issues. Everyting is falling apart--literally--throughout the entire play. But one thing that isn't up for question is whether these brothers love each other and that their uncle loves them. I like that that's cemented. The rest is, How are we going to get through the day or how are we going to get through the year. But it's not necessarily about the family being torn apart and having to be put back together.

The play does feel like it must be intensely personal. But it sounds like it's based on things that you know, but it's not based on you.

It is and it isn't. It would be a lie to say it's not based on me. I'm half Lebanese. My grandfather and my oldest aunt and uncle--my dad's brother and sister--were born in lebanon. And my dad's one of 10, he's the second youngest. My grandfather came over in his mid-twenties and was a tailor. So yeah, there are these sprinkled little bits of truth.

I'm fron Scranton [in Eastern Pennsylvania], which is close to Nazareth.

So, yeah, I'm drawing on my experiences. The best way to describe it that isn't a lie is that it's deeply personal but not autobiography. For me, I can go deeper and put more of myself on the line by having a shield of fiction. It just allows me to better ask the questions that are on my mind or just explore whatever the spark was that got me writing. Plus, my life's not that interesting.

I think why it's so appealing to a more mature audience is that it seems like the work of someone much older than yourself. For example, you're talking about The Prophet, which is something that I think a lot of younger people aren't as aware of. I will admit, however, that I was aware of it because when I was in high school I did have a theater teacher who gave it to me as a gift.

It's a great gift. You find it in a lot of bathrooms, like there in the toilet basket with the magazines. A lot of people don't even know he was Lebanese. So I guess he loomed large for me in that capacity. But he really is one of the bestselling authors of all time. The thing is, once you know about him, you start seeing him everywhere. His quotes are everywhere. I think I saw one on a bus on some MTA ad.

Also, you aren't following the formula many others seem to follow if they want a "gay play" to be popular.

What sort of gay play is that?

You write a play that has the gay scene, the sexy scene, in the first scene because the gay guys are gonna come back for the flesh. The nudity or kissing or whatever is loaded up front. So I thought it was interesting that you buried it.

I don't think I buried it. It just wasn't on my radar to exploit it. It was just the story I was trying to tell--but that's when the shirt came off. I mean, should Joanna Gleason done the first scene in a bra?

I guess an argument that doesn't interest me is, "Is this a gay play?" I mean, look, I'm a gay writer and I wrote a play with three gay characters in it. If you think that's a gay play then... There's a part of me that goes, "Yeah, that's a gay play." But I don't think of plays with straight people as heterosexual plays. I don't walk away from Death of a Salesman thinking of it as a straight play. I find it uninteresting because I don't care. If people want to call it a gay play, that's fine, but what I'm excited about is that I think audiences experience it as something... I think you get on the ride not with some marketing angle-- come to see Sons of the Prophet and you'll get some lovemaking in a Hampton Inn-- that's not the reason to see this play.

I do think it's a wonderful moment of transition. You get the older brother undressed and then he ends up in the hospital room. The way it was directed, it was really really well done.

It's one of my favorite moments of the show. It's something me and the director, Peter Dubois, had talked about, and he exceeded all of my expectations. We had talked about butterflies of sex the first time you're seeing someone undress. You know that feeling; they have all that build up in the bus station. It's where you first feel some sort of chemistry and attraction. To go from those butterflies to the butterflies of a doctor's visit. Those are the kind of ideas that may sound good and then fall flat. And Peter has given some of the most beautiful transitions. Nico Muhly's music is so perfect. It's one of my favorite moments in the show: when the motel goes away and you really don't know what's going to happen. And he just reaches behind the door and puts on a hospital gown. And everything shifts. That's what I love about theater. That's something you can't do in TV.

So tell me how it's different in the collaboration with Nico Muhly and Dark Sistersrather than writing a play.

It's a lot less lonely. It's more fun. It's more fun to have a partner in crime.

So did he contact you to work on it?

Well it was his commission, so the producers actually put us together. We had not met before, and they saw Speech & Debate. And they were looking for a librettist, and we just hit off. He's just so smart and so much fun. Not only did we hit it off, but his music is in Sons of the Prophet. It's a great collaboration where, his incidental music plays sort of a supporting role in the play, and I feel like in opera, it's just shifted around. The words are important but definitely take a backseat to the music.

I was curious: I read something you wrote something years ago for The Advocatethat dealt with the idea of coming out and how one must continuallycome out. It came up during the Out100 photo shoot when Senator Tom Duane said something similar. I wondered if your thoughts have developed any more on that topic. And I wondered if that seeps into the plays, if there are producers who say, "Why don't you just tone that down a little bit. Make it a little less gay."

Yeah, I feel that a lot. It's gotten easier I think. People were like, both of them? It's like when one of the schoolboard members says, "Gay and hearing impaired?" But I feel that I'm older now, and I'm in control of my craft that I could say, "Anyone who doesn't connect to this story, is not going to connect to this story no matter what the brother's sexuality is." Anyone who sees Sons of the Prophet and doesn't like it, they would not be won over--and I'm so positive of this--if it were about two straight sisters or two straight brothers. I just don't feel that's where the heartbeat of the show is. I don't know, maybe I'm giving people too much credit. But I just felt confident that it wouldn't make a difference.

But there comes a point where people are asking you to compromise something, and you have to say, "No." Right?

Yeah. And, I would say in their defense, they aren't even thinking of it as a compromise. They're basically thinking this isn't a play about the boys' sexuality, so, since this isn't a play about a coming out story, you could change it. But to me that was such a crazy idea because, as I told another interviewer, The Three Sisters is one of my favorite plays and I have never once read it and thought, You know, if these were three lesbians, I'd have more of an in to their thinking and be sucked into the story. And if I write a story with predominantly gay men, well, we've been connecting to stories with straight people for a long time.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right