Photography by Pierre et Gilles

"He toss my salad like his name Romaine, and when we done, I make him buy me Balmain," raps Nicki Minaj on "Anaconda," last year's hip-hop banger with the least subtle metaphors. Kanye West also name-checked the French luxury fashion house with his song "New God Flow," and Kid Cudi went so far as to title one of his tracks "Balmain Jeans."

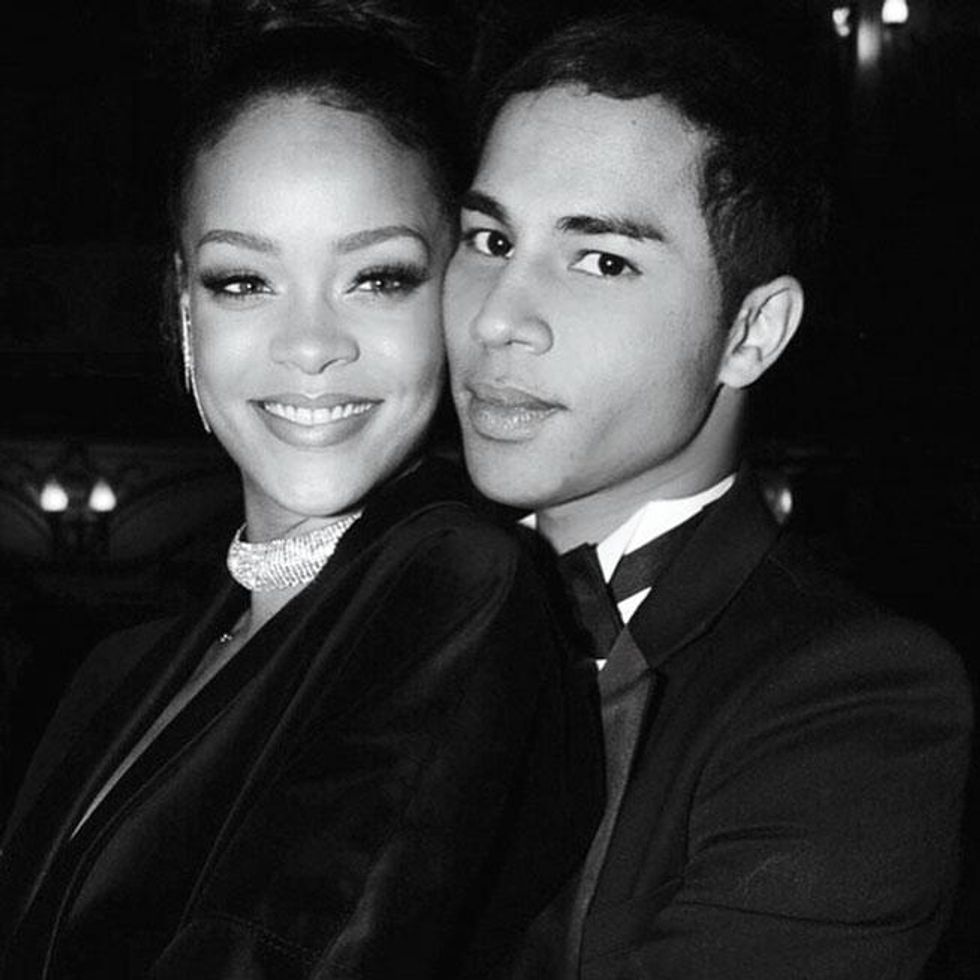

"When I heard Balmain in a rap song, I thought, We made it," says the label's 29-year-old creative director, Olivier Rousteing.

His astute statement sums up the stature Balmain has achieved since his appointment as head designer in 2011. No longer a label relegated to in-the-know fashion insiders, it has seeped into the collective consciousness. The current stars of the men's campaign are West and Kim Kardashian. Last year the face of Balmain was Rihanna. The two most memorable visuals at this year's Grammy Awards were Beyonce in a shimmering black dress and Jane Fonda in an emerald bell-bottom pantsuit. Both were designed by Rousteing. For the first time since its launch by Pierre Balmain in 1945, the brand has crossed the gulf into pop culture.

The same can be said for Rousteing himself. He's joined the pantheon of fashion designers -- such as Calvin Klein, Halston, and Versace (both Donatella and Gianni) -- who are nearly as famous as the celebrities they dress.

This is a Herculean achievement for a designer still in his 20s. But therein lies Rousteing's strength: youth. His social-media savvy is a main reason for Balmain's crossover. The company has 1.3 million Instagram followers, and Rousteing's personal following is just shy of that. To tail his comings and goings is to glimpse into a lifestyle that is just, well, fabulous: Rousteing with his razor-sharp cheekbones hobnobbing with the likes of Karl, Naomi, and just about every other celebrity cool enough to dispense with a last name. But Rousteing is quick to point out that his cyber presence is less a reflection of his life than a perfected version of it.

"Instagram is selling a dream," he says. "My Instagram is my perfect life, and I suck my cheeks in. Of course, I cry and have family or personal problems and am heartbroken, but I don't need to show that. It makes your life look cooler than it is. My job is to give a happy message about the brand to interest people. But at the same time, I keep it real. I don't fake my life."

It is a Saturday morning in February, and Rousteing is sitting in his office in Paris's affluent Eighth Arrondissement, just off the Champs-Elysees. He worked late the night before on his women's collection, and he's wearing a black T-shirt, a velvet suit jacket of his own design, brown Saint Laurent boots, and a Rick Owens snow cap. "I'm not taking it off because my hair is terrible," he says.

In many photos, Rousteing wears trench-deep V-necks and shirts unbuttoned almost to the waist. One would think that the part of his body he is most proud of is his chest, but that's not the case.

"My favorite part is my butt," he counters. "My face is getting older, and my chest is hard to work on, but the butt is the easiest thing to actually make look great. No one complains." Actually, the powers that be at Balmain have grumbled about his ass before and asked him to delete one of his Instagram photos.

"When I was in Mykonos, I posted a selfie in my bed almost naked," he says. "You could almost see my butt. But I love my butt. Why can't I take a picture of my butt? They said, 'Next time it's going to be your willy in the picture.' I said, 'No, just my butt.' "

Rousteing is sipping a coffee behind his glass-topped desk, sitting in a roller chair one would buy at Office Depot or Staples. The observation makes Rousteing laugh. "I don't need a gold throne," he says. At his fall men's presentation a few days earlier, he showed a collection of enormously baggy trousers (some in velvet and leather), louche belted smoking jackets, tasseled loafers, and beaded sport jackets. It had an haute-hip-hop meets chic-playboy-bachelor vibe. He says he found inspiration in '90s boy bands, like East 17 and Backstreet Boys, and rap. "It's badass but at the same time super aristocratic and royal," he says.

During Rousteing's tenure at Balmain, menswear has grown to account for 40% of the label's total revenue, and next season will see the brand's first men's runway show (as opposed to a by-appointment presentation). In July, the men's fragrance Balmain Homme will be released. When Rousteing spots his clothes on guys on the street, it triggers more complex emotions than the elation he feels seeing women in his designs.

"It's amazing with women, because I'm not a woman," he says. "It's a fantasy. I dream of the woman who wears the clothes. With men, I'm more picky, like, 'Oh, he shouldn't have worn it like that,' because that could be me. With men, I'm way more hardcore."

Rousteing, who is of mixed race, was adopted at the age of 1. "I don't see myself as black or as white," he says, "just human. When I was 11, I didn't realize my [adoptive] parents were white. My parents taught me when you are their child they love you. People in school told me, 'You are a bastard. You are black, and your parents are white.' I didn't know there was a problem."

Rousteing was raised in Bordeaux in southwestern France. "It's aristocratic, bourgeois, and religious," he says, "more so than Paris. It's really old French with castles, and writers like Mauriac come from there."

His father managed the seaport, and his mother was an optician. He speaks with them often. "They don't understand what I do, really," he says. "They say, 'Oh, I saw you on TV. Nice.' I go home and fight with my cousins, and they talk to me like shit if they want to. They don't care if I stay in a five-star hotel and have a driver."

Rousteing excelled in school, especially in math and languages (he speaks French, English, German, Italian, and some Greek). He wore Ralph Lauren and played soccer. His parents dreamed of his becoming an international lawyer. After finishing high school at 17, Rousteing studied law. He lasted a month.

"I think I would be a good lawyer," he says, "but it wasn't for me. I could do it, but it wouldn't make me happy." He transferred to an esteemed fashion school in Paris. He doesn't have fond memories of the faculty.

"I thought, You are teaching me shit. You look like a frustrated person," he recalls. "I was usually saying aloud what I was thinking, and they would say, 'Get out.' "

"I thought, My parents paid a lot of fucking money for this shit. I just felt that my teachers were rude and gross, and didn't understand what fashion was. They were talking to us like meat: 'OK, you dream of Dior and Versace? But fashion is not only that. You can be a designer of underwear.' Yes, but you can still be a designer for a big house! What do you do when you know you want to be part of the 2% and not the 98% who are going to do bras for supermarkets?"

Rousteing left after six months and at 18 moved to Rome. He briefly interned at a now-shuttered couture house and got his first boyfriend. "I know some words in Italian that I don't know in French," he says, "especially sexual ones. My sexuality was in Italian and not in French."

Soon he arrived in Milan to intern at Roberto Cavalli. For spending money, he danced in a nightclub. "I was dancing on a cube," he says. "I was not naked -- it was a glamour club. I'm a good dancer, and I had a huge Afro. We were doing fittings until midnight, and I would go straight to the club and change and dance. I'd finish at the club at 4:30 and go to the train station and go to Rome to see my partner, and Monday morning, I'd be back at 9. Just for love."

He stayed at Cavalli for five years, eventually becoming an assistant and then a designer.

In 2009, he joined Balmain, which was enjoying a fashion world renaissance thanks to then-creative director Christophe Decarnin and his skimpy dresses and exorbitantly priced skin graft-tight jeans. Rousteing worked his way up to head of the women's design team. In 2011, Decarnin didn't come out for the bow following his autumn show, which led to rumors about the circumstances of his leaving.

"The reality is that for the last couple of collections he was not feeling well, and I was taking care of them," Rousteing says.

Hiring a marquee name to helm a fashion house was derigueur then, and there was much speculation on Decarnin's successor. The establishment was surprised when several weeks later the then-unknown 25-year-old was announced as creative director. But it wasn't just his age and under-the-radar status that generated news.

"People were like, 'Oh my God, he's a minority taking over a French house!' " Rousteing recalls. "For me, I'm just French. Yeah, I'm black, but go out into the street -- there's black, white, Chinese, Arab..."

Still-rampant racism is all the more glaring in an industry based upon image. It is most evident in today's all-white runway shows and campaigns, but the underlying problem is the corporate and creative structure behind the scenes. It's one thing to have models of color on the runway, but a bigger stride -- and rarity -- to have a non-white creative director. Whether he wanted the responsibility or not, Rousteing had the duties of role model and groundbreaker foisted upon him. It has made him think about race in fashion conceptually, and also about his place in changing the status quo.

"Look at perfume campaigns," he says. "You never see black girls, and if you do, they use Photoshop so much that they almost look white. It's just wrong. People post on my Instagram that they are so happy to see black boys and black girls. I'm happy that they see it and don't think that fashion belongs to white people. Comments on my Instagram are more important than what critics say. It's deep. I don't care if you think my shoulders are too big or too small this season. I don't care if you think my coat isn't oversized enough."

He pauses and adds: "It's going to sell anyway."

It seems that Balmain was expecting a continuation of Decarnin's profitable cult following. Initially, Rousteing adhered to the previous design DNA and carried the torch. "When I got the job, I was trying to please the entire world: my president, the customers, my front row," he says. "But after four seasons, I realized if I want to keep my job -- or let's be honest, if I don't want to quit -- I need to wake up in the morning and please myself." To its great benefit, in Rousteing, Balmain got an outspoken game-changer and a star. A privately owned company, Balmain won't release exact figures, but it says that growth of the brand is between 15% and 20% in the last three years.

"Without doubt, the biker jean is the runaway success," says Tom Kalenderian, executive vice president for menswear at Barneys New York. "It is the icon of the brand. Olivier Rousteing's Balmain is a world of deconstructed opulence. There's something magical about the irreverence that makes these clothes coveted."

Rousteing leaves his office, drinking water and lemon juice, a recommendation from his boxing trainer, whom he sees each morning before work.

Walking down the sidewalk, he says, "The cool thing with Paris is there is nothing to do, so you stay in, sketching with a glass of wine instead of going to the worst club ever. We make beautiful collections because we have nothing else to do. It's a museum."

Balmain is a quintessentially French brand, and I point out that there's a disconnect in having American royalty like Kim and Kanye as campaign stars. "I don't think so at all," Rousteing says. "French people think I'm less French than before, and I think I'm way more French. Kanye and Kim have this new French taste. They are the new French couple. They love Alaia and Jean Paul Gaultier. They actually wear French designers."

He continues, "You need to have someone from outside to make you want to rediscover Paris. I needed to have Americans in my campaign. She is American and Armenian and has a mixed-race baby. That for me is what I want to show. They're global. Paris and Balmain need to go global."

A Balmain store opened in London in February, and the first New York outpost is coming in the fall, all part of a broad campaign of rollouts. We go into the Balmain flagship a few blocks away, on Rue Francois 1er, a marble temple of luxury that Rousteing visits once a week. "You see the real customers," he says. "Sometimes they want a selfie. You actually see what they buy and how they react to a collection."

He greets a saleswoman -- "Bonjour, vous allez bien?" -- and walks up the grand staircase to the second level, past an intricately hand-beaded mini-dress that sells for 16,000 euros and through the men's section (a T-shirt is priced at 315 euros).

"Balmain makes people dream," he says. "When they can't afford the dress, they'll buy the pants."

He sits on a velvet couch, and a staffer brings him an espresso. "Nobody teaches you how to face success," he says. "That's something you have to learn when you get it. It's pretty hard."

Rousteing dates casually, but he hasn't had a serious boyfriend since he lived in Italy. "I don't know how to manage a private life," he says. "I don't know how to wake up next to someone. I don't know how to share my private life with someone. That's something I need to work on. It's important to trust someone and laugh and cry when you can."

Relationships in general have become more complex. "I can see some friends who didn't care about me before, but now they love me," he says, "even though they haven't spoken to me in three years. You get some new friends, and you don't know if they're true. And relationships -- you don't know if they like you because you are you or because you are the Balmain man. That's the most difficult thing in my life. My job is OK. My private life is what's complicated. I can't use Grindr. This is something I avoid. I mean, I could. What's the problem? Everyone wants to have a sex life, but it's not something that excites me."

He continues: "Some of these burnout designers who get crazy, they are not connecting to the world. With Instagram you have the chance to connect to real people, not just the critics and 10 employees who will lick your ass to keep their job. With social media, you get comments that sometimes help you to grow as a real person. There are so many examples in fashion where people get crazy. If I get crazy, I want to be happy crazy, not a sad person."

Overall, Rousteing exudes a grounded, upbeat vibe, and seems devoid of the pathos, self-flagellation, and destructive tendencies that can lead to designer meltdowns. "I want people to be real with me," he says. "Designers sometimes don't want the truth. That is what makes you feel like shit -- when everyone around you is not true. I need people around me to say, 'fuck you' when they need to. It's really easy to become a beast when you get everything. I'm very young for what I've got. Everything that's happened to me at 25 usually happens at 40. I'm scared I'll become this rude, selfish beast with no patience. I'm really scared of myself."

He takes a sip of his espresso and sets it down on a silver tray. "Being connected in every sense is the most important thing," he says. "You have to be connected to the world."