The first time Aaron Levine visited the Abercrombie & Fitch corporate campus, 20 miles outside Columbus, Ohio, it was spring. It's easy to see why he fell in love with it. At that time of year the compound is surrounded by lush greenery, strewn with bleached-wood cabin-style buildings, like a quaint storybook village nestled in the woods. The day I was there, in May, the verdant backdrop was practically glowing, and at lunchtime, local food trucks filled the parking lot where cargo-shorts-wearing guys and girls in flirty camisoles and denim cutoffs lined up for artisanal tacos. It had the appearance of an idyllic liberal-arts college--or an Abercrombie & Fitch advertisement come to life. For Levine, the appeal was powerful enough to make him ditch his fancy New York job with Club Monaco and move with his wife and twin daughters to take up a position as head of men's design at the ailing teen retailer.

"It's not what I was picturing," Levine says as we meander one early afternoon while employees casually whiz from building to building on Razor scooters. "But more than the campus, the most seductive aspect was the people you talk to. The people that you interact with here are super intelligent. Nice. Calm folks." He stops, before adding, somewhat obliquely, "We've got complex challenges to solve, but you're doing it with smart, nice people, so it makes a difference." Of his commute to work, he says, like an awestruck city slicker gone rogue, "Literally there are days when I don't see any other cars. I pass cows!"

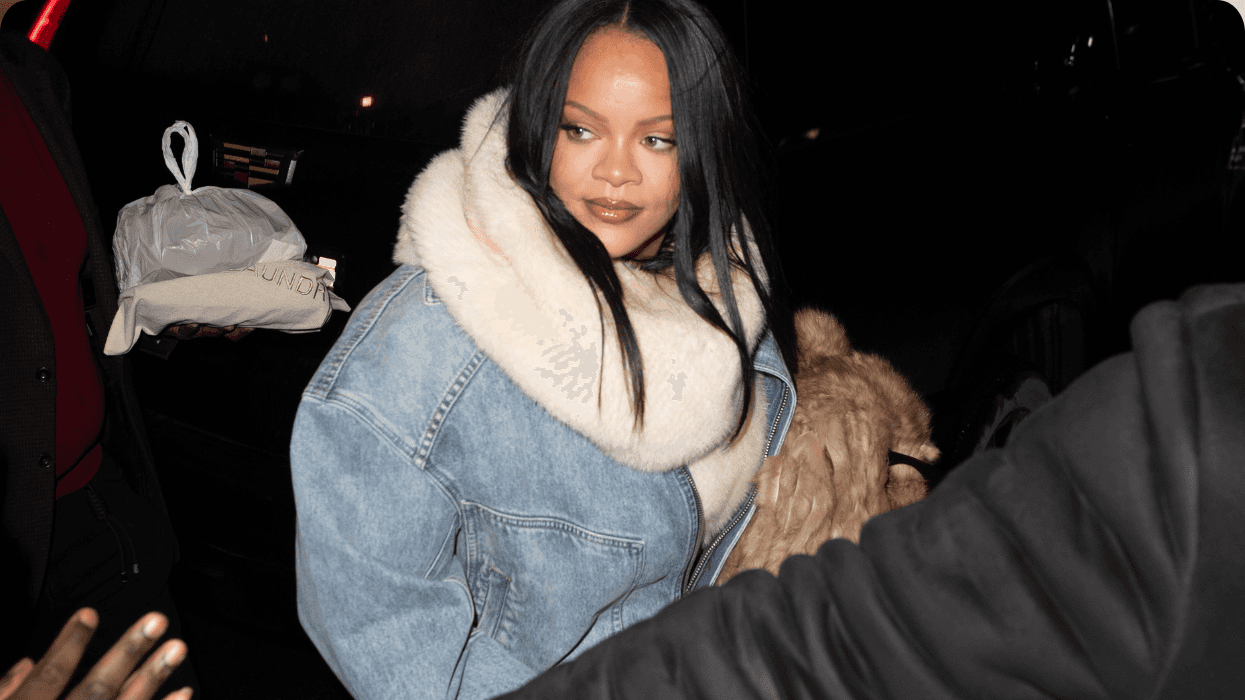

Levine was hired in June 2015 as head of men's design, but was promoted last year to oversee the brand's entire offering. He has a dopey but curious energy and sports a dark, bushy beard shot through with gray, and thick, expressive eyebrows that almost touch. He's a big fan of the Grateful Dead. When we meet, he's wearing all Abercrombie: a dusty-gray T-shirt, light-wash denim, an army-green button-up shirt jacket, and a beanie over his long hair. The one exception: a pair of suede Birkenstock clogs, which he somehow pulls off. In 1999 he was an assistant store manager in Richmond, Virginia. A far cry from the archetype of the imposing fashion designer uttering dictates in some glass-and-steel Manhattan tower, he's more of a cross between that hippie kid who was always hanging out on your college's quad and a really cool camp counselor.

Aaron Levine

Over the past few years, though, Abercrombie has struggled to find its footing, as a new generation has come of age in a vastly different era, one in which the internet has replaced magazines, social-media influencers hold more sway than celebrities, and inclusivity and a fine-tuned awareness of social issues--being "woke"--has elbowed out the idea of selling desire, which has long been a tenet of Abercrombie's once-landmark business approach. Fast-fashion brands like Zara and H&M have been able to replicate runway trends quickly and cheaply. Malls have been closing at an alarming rate in recent years, and millennials and Gen Z shoppers now prefer to spend their money on experiences--a road trip, or a weekend at a music festival--over clothing. Teen retailers, in particular, are struggling to stay aligned with their consumers' ever-changing desires, fed by endless streams of visual information fueled by Instagram and Snapchat. American Apparel filed for bankruptcy last November. Investors are offloading shares in Urban Outfitters. In April, J.Crew said it was cutting 150 full-time jobs, and the vaunted creative mastermind Jenna Lyons announced her departure. "I've never seen the speed of change as it is today," J.Crew CEO Mickey Drexler acknowledged in June. "If I could go back 10 years, I might have done some things earlier."

In May, Abercrombie reported a first-quarter loss of $62 million, with rumors swirling of an acquisition--possibly by its current rival, American Eagle. The financial news can be harder to decipher. Stocks have been trading higher, thanks to the acquisition rumors, but the company recently reported that same-store sales fell, albeit at a lower percentage than expected. In such tenuous times, any wrong step could be catastrophic. Case in point: An effort to show its support for Pride this year failed horribly when the retailer posted a tweet quoting an employee announcing that "The Pride community is everybody, not just LGBTQ people." Social media was quick to respond--and merciless. (To its credit, the company has received a 100% score on HRC's Corporate Equality Index for the past 11 years).

While Levine, on first appearance, may wear his responsibilities lightly, he carries a heavy burden: shepherding Abercrombie into the future. "There's some sleepless nights," he admits. "But only because you want it to be as good as you know in your guts it can be."

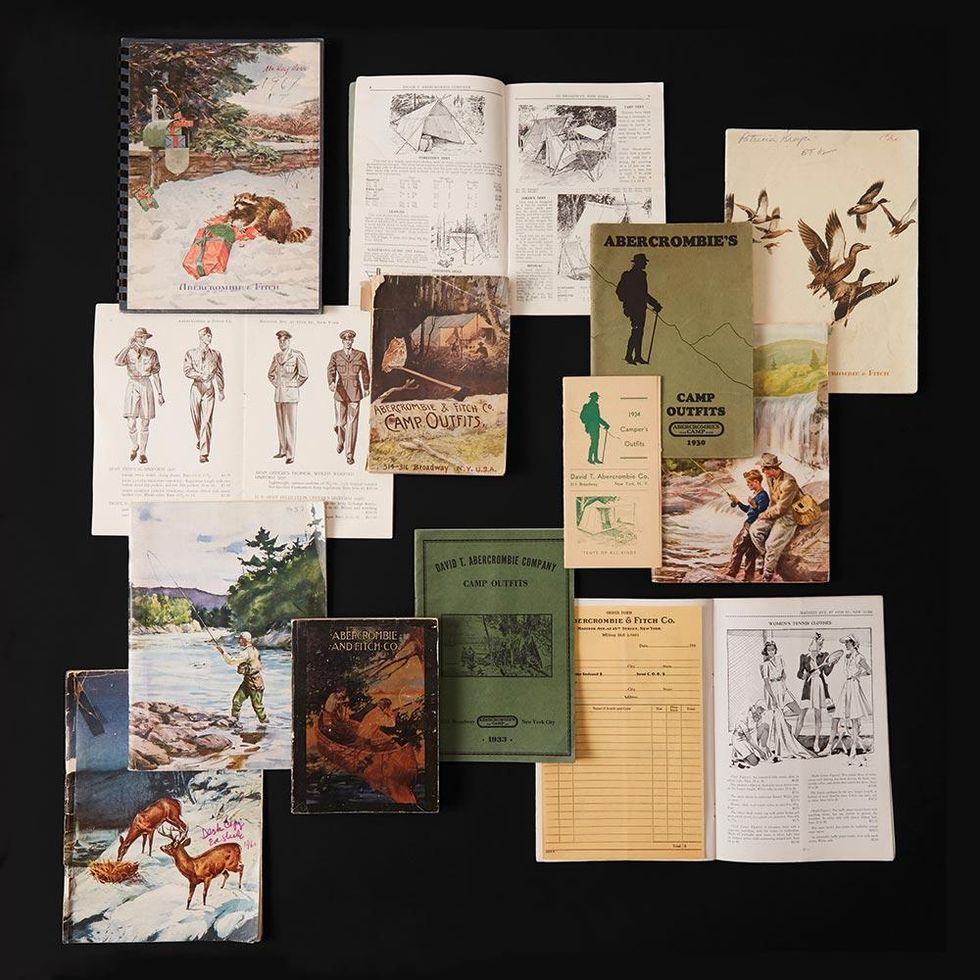

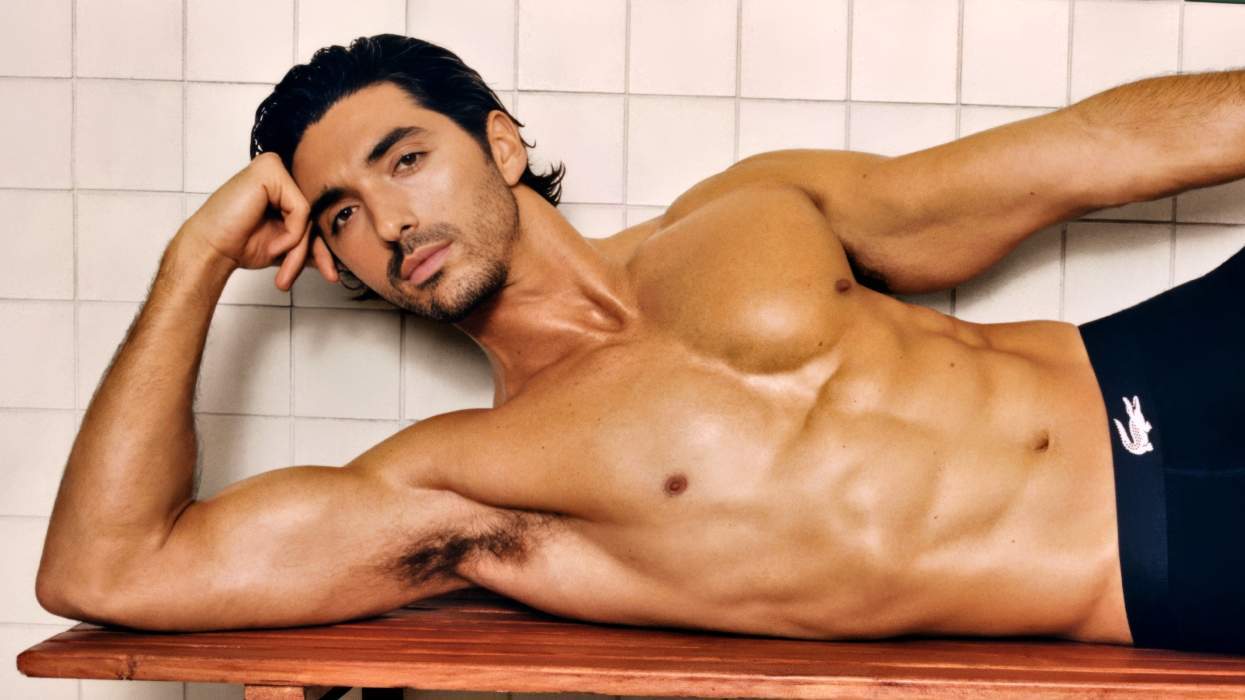

Abercrombie & Fitch is an $876 million business with more than 250 stores in 20 countries, a teen retailer known for selling a certain type of wholesome casualwear imbued with a knowing wink. Founded in 1892 as a purveyor of camping gear, it's a true American heritage brand with a rugged history: Teddy Roosevelt and Ernest Hemingway wore its clothing on outdoor expeditions. Amelia Earhart had a custom A&F jacket made for her. In the early 1990s, when the brand was transformed into a fashion powerhouse by then-CEO Mike Jeffries, that history was instrumental in recasting it as a paean to athletic American youth, selling suburban ennui and the dawning sexual possibilities of adolescence manifested as slouchy, sun-faded hoodies or artfully worn-in denim. For people of a certain age--early 30s, say--Abercrombie immediately conjures images of dark, cavernous stores filled with thumping club music, polo shirts adorned with moose logos on the chest, and wall-size black-and-white photos shot by Bruce Weber of men with rippling abs.

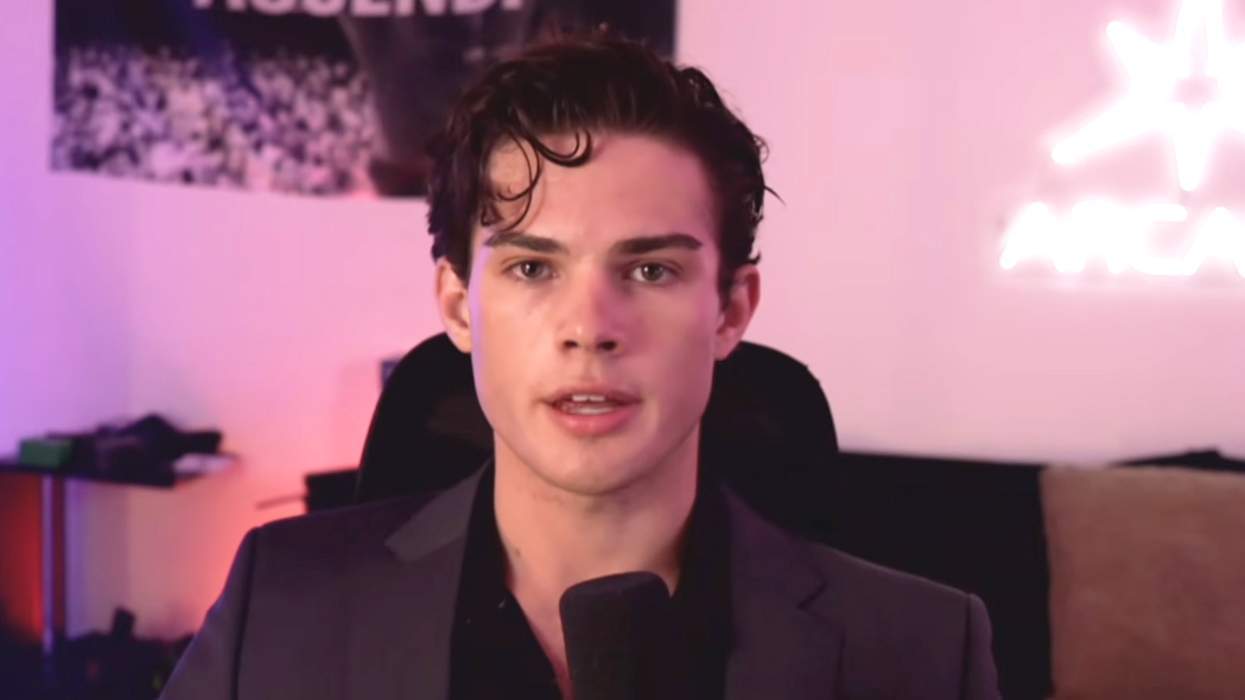

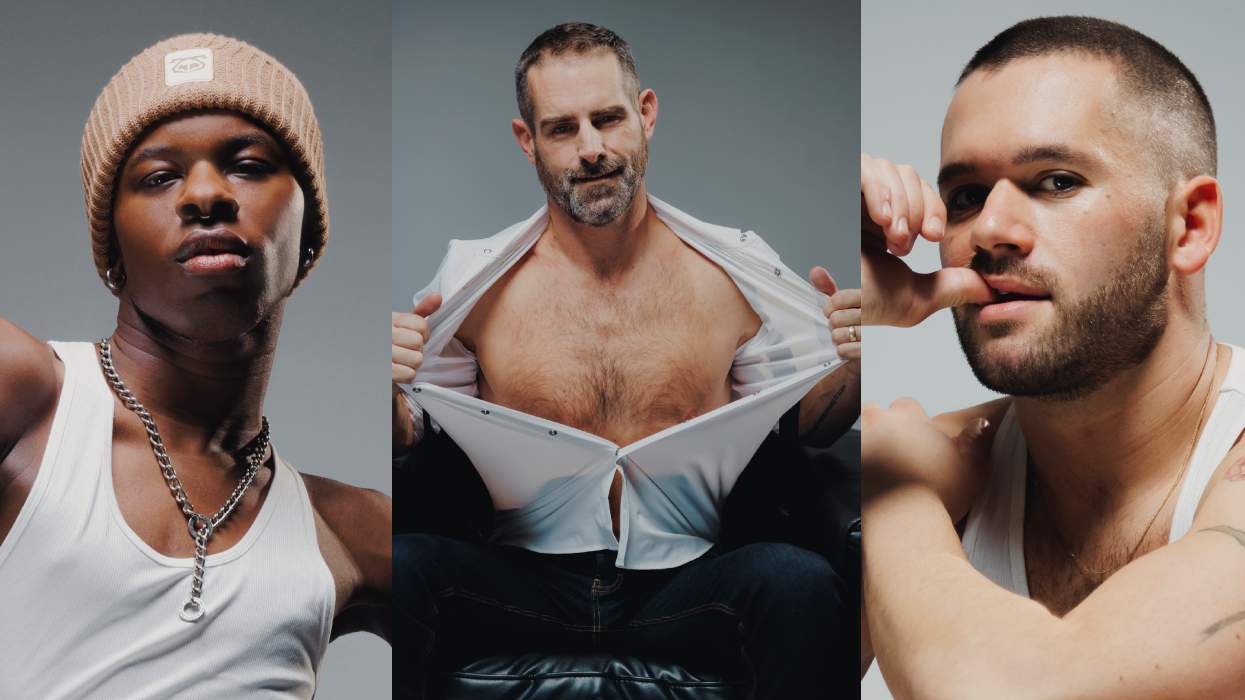

A&F's new brand

If Calvin Klein represented sex and Ralph Lauren represented romance, Mike Jeffries should be recognized as a man who took the two and blended them into pitch-perfect marketing that spoke to the aspirations and anxieties of an era. But fashion is a business built on change, and Jeffries failed to evolve with the times. His eccentricities--frosted hair, ripped jeans, flip-flops--were at first novel, and then finally irksome. Remarks that once passed without censure now faced the scrutiny of social media. Jeffries had a liberating attitude toward sexuality--a 2000 issue of the A&F Quarterly even included a lesbian wedding scene--but his A&F was also exclusionary, ageist, and very white. "We want to market to cool, good-looking people," he told Salon in 2006. "We don't market to anyone other than that." It's telling that his quote only came back to bite him in 2014, when social media exhumed it from the past. Jeffries stepped down shortly after.

So where is A&F heading now? "Our point of view is that we're trying to make the ultimate casual luxury brand experience, right?" Levine says. "It needs to feel intrinsically American, and easy and lived-in and animated. It needs to have attitude. Our pillars are vintage military meets prep meets varsity athletic, and then mix those together. That's what gives us our aesthetic."

Attempting a turnaround at this scale is no small feat. Luxury labels--the Diors and Louis Vuittons of the world--oftentimes have limited real-world influence compared to their high visibility. A brand like Abercrombie, however, dresses large swaths of America and, more important, young people in America. "I think you build things with honesty and integrity and beauty and then that resonates," Levine says. "The stuff that we're putting in stores right now is exceptional, and the value is incredible." A rack of four-figure clothing at Barneys available to the one-percent is nice, of course, but having hundreds of stores across the country means your pieces can touch the bodies, not to mention the lives, of many, many people. "There's a lot we want to do, and we want to do right by our customer," Levine says. "It's very freeing and it's very exciting, but at the same time there are people here who are very serious about their craft and about their profession and about evolving this brand and making it iconic again."

Legacies are a tricky thing. It's both a blessing and a hurdle to work for a brand with such a rich history, learning when to rely on it and when to let it go. The past can serve as a springboard for the future, but it can also limit your creative freedom. Levine's job is to help his team find a balance that feels both retro and fresh. "We're going back into our history and pulling out elements and then mushing them together," Levine says later, surrounded by gauzy vintage photos of rock stars and artists in a drab, windowless room that serves as the incubator of next season's big ideas. It's here that he and his crew--he's very clear that this is a team effort--start the months-long process of designing a seasonal collection, of shaping the way teenagers will dress in the future. "This is the room that it starts in," he says, gesturing broadly to this unexceptional space crammed with pictures and piles of clothes lit from above by fluorescent lights. "It's a big brand, but it doesn't feel like that. It feels like it comes from a place of love and inspiration and honesty."

Vintage A&F

Under Levine, Abercrombie's aesthetic has been streamlined, moving away from the flashy logos that were once at the heart of the label, toward something more sophisticated and simple. For summer there are some tab-collar linen popover shirts that fall somewhere between a tunic and an oversize Henley tee, and a fleece-lined denim jacket that looks like it was plucked from the local thrift store. They're bits of quotidian Americana, rendered with a certain studied insouciance. Many pieces are garment-dyed, which gives them a mellow richness. Cargo pants, a brand staple, are trimmer than they were, a savvy update. Levine and his team have even embraced athleisure, with a sportier line, though Levine points out that he wants to keep it "crunchy." What's striking is how undesigned it is, how plain and straightforward and, in its way, sweet and earnest. It is free of overt references. It's clothing for Anytown, USA.

The best place to see Abercrombie's future in action is at Polaris Fashion Place, a mall some 14 miles out of Columbus's city center. It's where the retailer's new store design has been fully executed, and it's vastly different from its previous incarnation. In the late '90s and early '00s, Abercrombie stores were known for their imposing energy, with aloof, attractive salespeople and a moody, exclusive atmosphere, like the VIP section of a cool club. Jeffries thought of the store as integral to the brand's identity and mapped out every detail. "It became an experience," says Robert Burke, the founder of Robert Burke Associates, a consulting firm that specializes in retail. "Between the darkly lit stores and the loud music, the fragrance spray, the shirtless boys everywhere, and the lines outside, it became something that you had to experience." New York's flagship Fifth Avenue store often had a line snaking out front. Today the store is a colossal expense that has long ceased being the magnet it was designed to be. It's a showpiece, but the show is no longer filling the house.

The way we sell things and the way we shop is, in many ways, the story of who we are. The swaggering confidence of the turn-of-the-century American retail scene has mellowed into a quieter, more introspective mood post-9/11. The new store concept reflects this mood and lacks the hard-nosed commercialism it once possessed. At Polaris, the store welcomes with light patinated wood floors, cool blue walls, and a central runway with mannequins sporting easy, casual outfits. The A&F logo has been reimagined in a subtler, whimsical cursive and is emblazoned on the dove-gray ceilings among bronze accents. The space is airy and has a calm, upbeat vibe. To appeal to tech-savvy, younger shoppers, the dressing rooms are now the center of the store, with charging stations for phones, adjustable lighting (for that perfect selfie), and shared spaces to make the shopping experience feel more social.

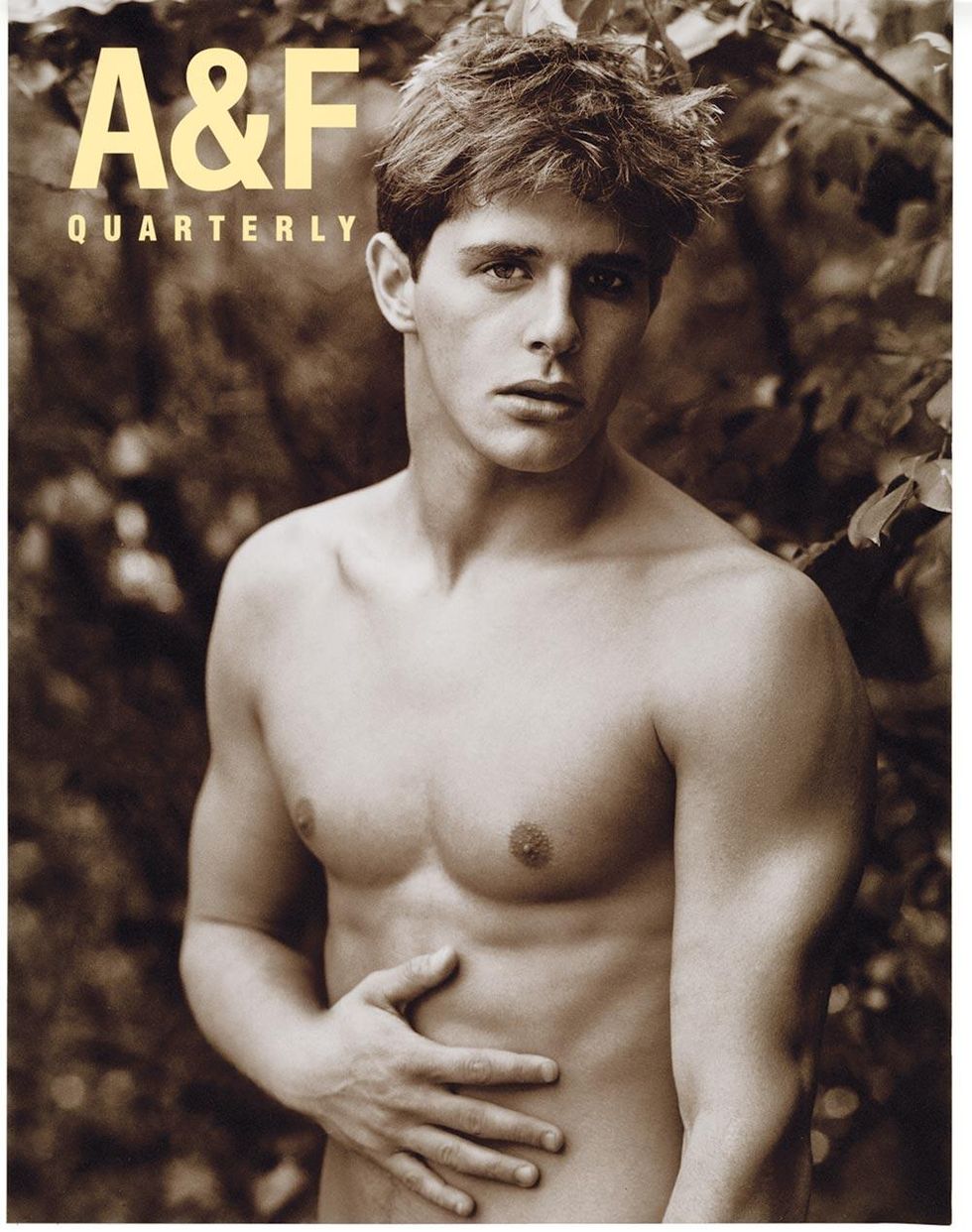

A&F Quarterly

For another glimpse of the new Abercrombie, look to its recent ad campaign, titled Made for You. In the 1990s, A&F's advertisements, plus the supplementary branded magazine-cum-look book known as the A&F Quarterly, were iconic and oftentimes controversial totems of the era, lush picture books printed on thick-stock paper. These playful, hyper-sexualized photos of scantily clad men and women with a fresh-off-the-farm cornfed look were seared into the minds of teenagers of the time (countless gay boys no doubt felt their first sexual stirrings while flipping through the catalog's pages) and set the tone for advertisers of this period. "We couldn't wait to see what we did next," says Sam Shahid, who served as the art director of the brand at that time and credits Jeffries's strong leadership for helping to create such iconic images. He remembers getting hundreds of letters each week, submissions from people hoping to model in the catalog. One time during a photo shoot in Times Square at 2 a.m., a group formed and started screaming, like some second coming of Beatlemania. "It was about connecting to what kids want. It was like movies. We were telling stories," Shahid says. "It was very free--we never thought it would shock anyone." Taylor Swift, Channing Tatum, Jamie Dornan, Jennifer Lawrence, and Ashton Kutcher all starred in these campaigns over the years, long before they were household names. As Burke puts it: "Bruce's photos were about running around campus and getting laid."

Related | Gallery: 5 Iconic A&F Quarterly Covers

The new campaign features street-cast young people, as opposed to professional models, from across the country, sharing their memories of the brand, which Abercrombie hopes helps to leverage its cultural imprint and entice a new generation. "People have a lot of emotions about what the brand was, but they don't have as much emotion about how that will connect with them today," says Stacia Andersen, Abercrombie's brand president. Andersen is a Midwestern gal with wavy blonde hair, a broad smile, and a friendly way of talking. She joined the brand after 23 years at Target.

"I came here because of the story we all want to make here," she says. "Look, I was the kid in the ad, I grew up with Abercrombie. I believe this brand deserves a comeback."

But what's a comeback to a generation that doesn't have fond memories of the label? They come to the brand with fresh eyes, no hang-ups, but no context either. When I had a conversation about A&F with my 15-year-old niece recently, she said it was in her top three brands, along with American Eagle and Hollister (which Abercrombie owns). I asked her why, and she thought for a moment and said, plainly, that it didn't try too hard.

Teenagers, too, don't want to try too hard. Looking cool is, in part, doing so effortlessly. Because as long as there are teenagers, there'll be people who want to forge their own path and find a style that defines them. Abercrombie is planning to make it through these challenging times long enough to still be there to help them.