To most outsiders, gay Manchester is known for one thing: Queer as Folk. The seminal and slutty drama premiered in 1999 and centered on three gay men living and cavorting around the city's Canal Street before being adapted for America and relocated to Pittsburgh. For many Mancunians, though, the TV show's success was double-edged, because as well as celebrating the scene, it arguably hastened the death of the gay village.

"Queer as Folk had a massive effect on Manchester," says Jamie Bull, one of the city's prominent DJs. "Almost overnight you could feel people turning up as tourists. The secret was out."

Setting foot in Manchester as a student the year after Queer as Folk debuted, I expected a gay utopia, but instead found mainstream gay life to be a grim mix of 2-for-1 binge drinking, bachelorette parties, and terrible music. Luckily there was an antidote in the form of Homoelectric, a new underground gay party that played everything from deep house to Destiny's Child and had a framed photo of Martina Navratilova behind the bar. I had arrived!

The strapline on Homoelectric's flyers screamed that it was "For Homos, Heteros, Lesbos, Don't Knows," and the hosts gave out badges bearing the command-cum-invitation: "Be Ugly." The whole production was in the same radical vein as the "queer as fuck" flesh parties that took place in the city's legendary Hacienda nightclub in the early 1990s. Homoelectric reminded Manchester's LGBTQ community that putting music first and sex second can make for a safer and more sustainably ecstatic experience, and it went on to inspire parties like Bollox, High Hoops, Meat Free, and Body Horror.

It's these nights and the communities that have built up around them that Stephen Isaac-Wilson explores in Fleshback: Queer Raving in Manchester's Twilight Zone. We spoke with the London-based filmmaker about the city's underground, cultural appropriation, and "the politics of ugly."

Why did you choose to spotlight Manchester?

What interested me was the anything-goes nature of these queer nights, compared to London. There was less interest in who people know, it was very intergenerational, the music was by resident DJs who knew their stuff, and it didn't feel elitist. A lot of these nights were run by people with an innate interest in music, and they didn't want to become DJs to leverage a different type of media career. They worked regular office jobs, but their aim was running a really cool party for their friends, rather than trying to be an Instagram superstar.

I always found that the nights in London revolved much more heavily around fashion and aesthetics, like Taboo and Boombox, than those in Manchester did.

That's the whole thing. It's not about what you look like. People just want to have a good time. [In the film], they also talk a lot about the politics of being ugly at Homoelectric, where it's not about having a dream body. It's not about looking hot.

There is such a strong local mythology around clubbing in Manchester, but when you come to London, you realize that no one is aware of it.

Because none of the nights are branded, people don't realize how avant-garde they are. They're just making it happen, rather than marketing it as such. These nights don't have big social media followings. There aren't pages and pages of articles about them.

Musically, there's a long-standing relationship between Manchester, Detroit, and Chicago, and this constant back-and-forth between the gay and black music scenes.

I think there's definitely something tricky about the way Manchester borrows or repurposes music forms, like when Northern Soul happened and influenced how people dressed and what they wore. You could say that some things blur into cultural appropriation, but I thought it was quite interesting to watch it, because they're trying to create a really interesting space and time. I think that's something that London doesn't do. People there recognize where a lot of their stuff comes from.

When I lived in Manchester, cultural appropriation wasn't deliberately on the agenda. Everyone was celebrating the idea of mixing cultures, so I wondered what a younger generation's take on it would be.

I definitely saw things where I thought, This wouldn't wash in London, but the thing is, I don't think anything was done with malice. Their stories were more important than the clothes they wore. Also, this is a documentary, not a music video where you can control the image. Documentaries are about people telling real, authentic stories.

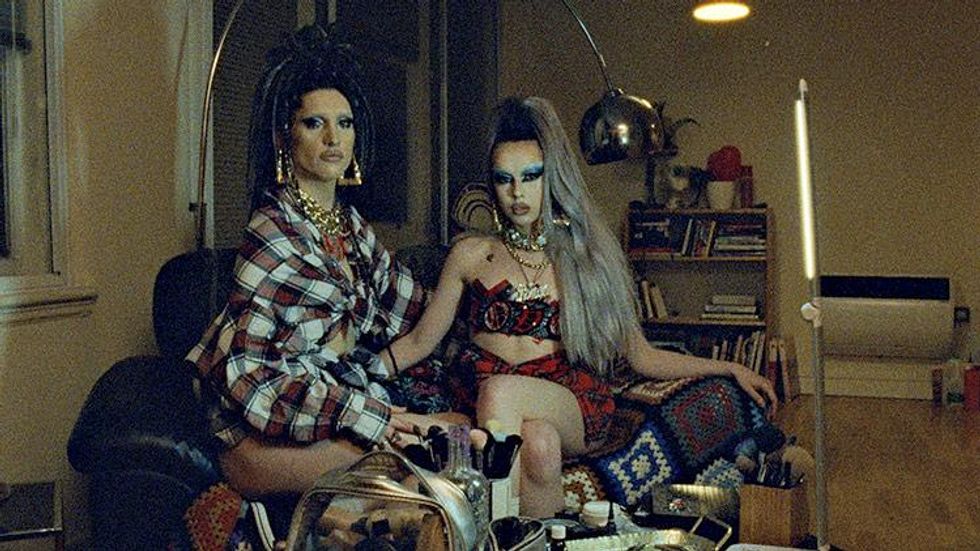

Courtesy of Stephen Isaac-Wilson