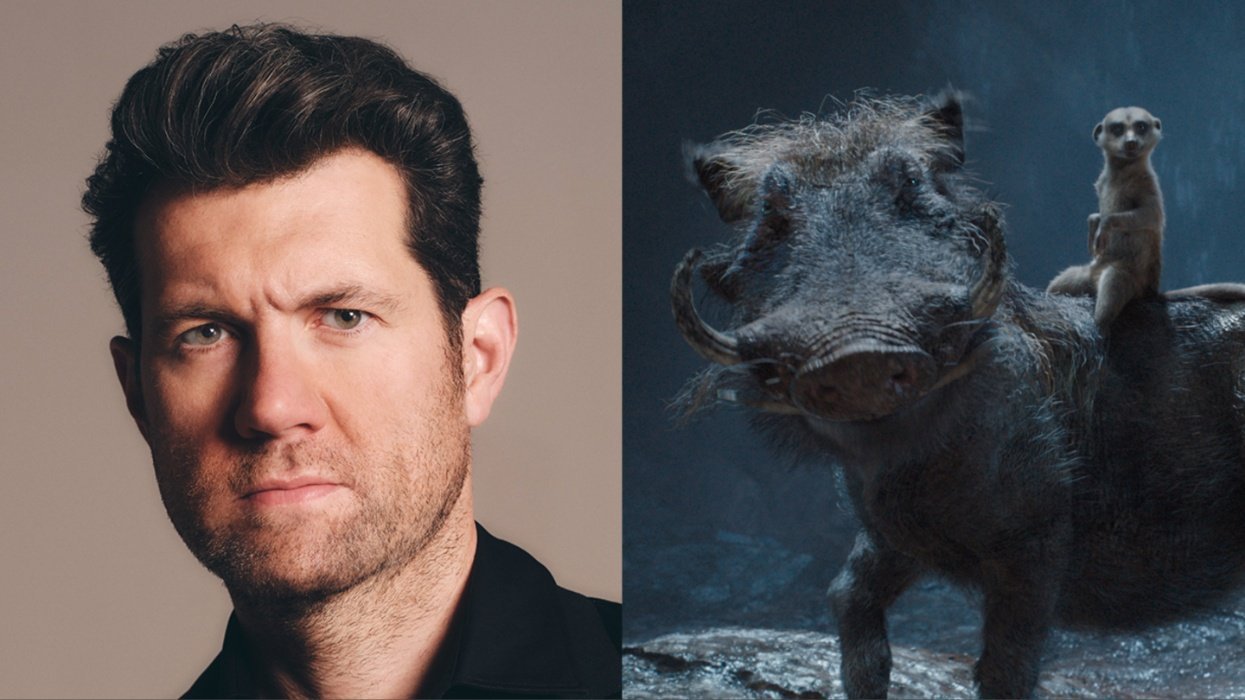

Pictured, from left: a Pieter dress for spring 2015; J. W. Anderson's crop top for spring 2015; Thom Browne's voluptuous silhouette for fall; Prada's sheer knits for fall. (Credit From left: Andrew Urwin/Courtesy of Sebastiaan Pieter; Courtesy of J.W. Anderson; Catwalking/Getty Images; Courtesy of Prada.)

How much does fashion really impact our attire? As received opinions run, menswear doesn't fluctuate all that much. Womenswear is subject to oscillating hemlines, vagaries of fit and flare, to ever-perambulating erogenous areas. Shifts in menswear, we are told, are tectonic, stately and slow: they mean something. They're allied with events like war and revolution. Think of the Great Masculine Renunciation, the term coined by the psychoanalyst John Carl Flugel to denote a general eschewing of extravagance in male dress at the turn of the 19th century. It was a revolution in cloth, a sartorial equivalent to the upheavals recently wrought in the Americas and France. In fashion terms, it swept away the restrictive layers of finery, slicing off embroidery as Robespierre cleaved off aristocratic heads, in favor of stripped-back tailoring in black and navy blue.

That's the sort of heavyweight stuff that changes the course of menswear, we like to think, rather than the flimflam of the biannual catwalk circus. The shows are, by and large, very much like the courtly attire of the ancien regime, where tinkering with outward trinkets of embellishment hid a lack of evolution in cut. How dishonest. How dull. How wrong.

"There is an influential new guard of designers who are questioning the fundamentals: gender identity and sexuality, the roles and position of the postmodern male"

Today, however, a menswear revolution is being wrought on the catwalk -- admittedly, by relatively few. Many cling to the accepted stock characters of men's wear, jiggling prints and trims on stalwart but staid suiting, or sportswear basics barely tweaked from their track and field origins. But there is an influential new guard of designers who are questioning the fundamentals: gender identity and sexuality, the roles and position of the postmodern male. There was a similar upheaval 20 years ago (really, that long ago) when designers like Alexander McQueen, Helmut Lang and Martin Margiela broached ideas of power and masculinity, of uniformity and modernity, and of luxury, respectively. Come to think of it, those ideas were addressed in women's fashion by Rei Kawakubo and Vivienne Westwood a decade earlier. Womenswear today, however, is safe. Its provocation is superficial: the juxtaposition of this season with the last, the jarring of fashion following fashion. And the relentless speed.

Menswear, without the churning rate of precollections and the occasional interruption of the high camp, high art and highly irrelevant haute couture, is breeding the talents truly questioning the status quo. Arguably, that's because menswear quo is far more static; it's easier to rattle cages in menswear. Jonathan Anderson, who designs for men and women under the labelJ. W. Anderson in London, as well as for Loewe in Paris, agrees: "Especially in menswear, which is just a flat line of rehash and nonmodernity, you need something modern to happen." Anderson is responsible for plenty of ideas that may, generously, be called modern. They're certainly thought-provoking. In his fall men's show, every model teetered out atop stack-soled platform brogues, and many clutched undersized purses or sported bowed blouses like parochial schoolmarms. This is par for the course for Anderson: A year ago, he cut a sequence of ruffle-hemmed shorts to sit flat across the groin because "to flat-surface that area is kind of disturbing for people." The collection also featured an intarsia-knit silhouette of shears. Anderson stated they were "castration" scissors. For womenswear, while Anderson does clever stuff with texture and bonded fabrics, the confrontational edge is often missing. It's about the surface, the material. Literally. They should be more. Clothes are politicized objects, a sartorial billboard, a manifesto on your back. You can still be arrested for wearing the wrong thing in the wrong place -- and, beyond the laws of basic public decency, that's because people often don't want to hear what your garments are telling them.

"Today, designers actively court the effeminate. Why? Because it's a reflection of the reality of the lives they, and many of their customers, lead"

That isn't specific to men, of course. But, as Anderson's work aptly demonstrates, the boundaries of menswear are easier to transgress, and the clothes often incite far more excitement and outrage when their conventions are challenged. Maybe that's because the standards are white, middle-class and heteronormative -- established by the people who most frequently throw up their arms in despair when fashion throws down an especially extravagant gauntlet. Anderson's oeuvre only adds to a provocative whole. London is a breeding ground for such aesthetic affronts, all the more outrageous given the city's reputation as the birthplace of the three-piece suit.

Pictured: Astrid Andersen spring/summer 2015

In addition to Anderson, there is the London designer Craig Green, whose fall menswear collection featured intricately patterned floor-skimming skirts and coats with a ceremonial air, and sportswear-focused designers like Astrid Andersen. These designers are still suiting men, but in alternative gay apparel. Quentin Crisp outlined that men of the '20s "searched themselves for vestiges of effeminacy as though for lice." Today, designers actively court the effeminate. Why? Because it's a reflection of the reality of the lives they, and many of their customers, lead. Not all fashion designers are gay; however, a large proportion are, and a fair number of their customers are, too. There's a honesty to, for instance, the work of the young London-based designer Sebastiaan Pieter. He creates collections under a label he's named Pieter, inspired by saunas and the gay dating app Grindr. He does a neat line in dresses: one, in flesh-toned wool jersey, has a fly zip because it's a dress for a man, he explains. At first, that irked me as a deliberately titillating point of emphasis; not that men don't emphasize their groins in all kinds of ways, but this seemed a little extreme. Then, the practicality convinced me of its validity. It's a clever fusion. Pieter himself wears his own dress styles as well as those created by Rick Owens. The lack of a fly was an impediment. He offered a practical, albeit provocative, solution.

This is excerpt from "Sign of The Times: A Men's Wear Revolution" at T: The New York Times Style Magazine. Read the full story here.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right