Film

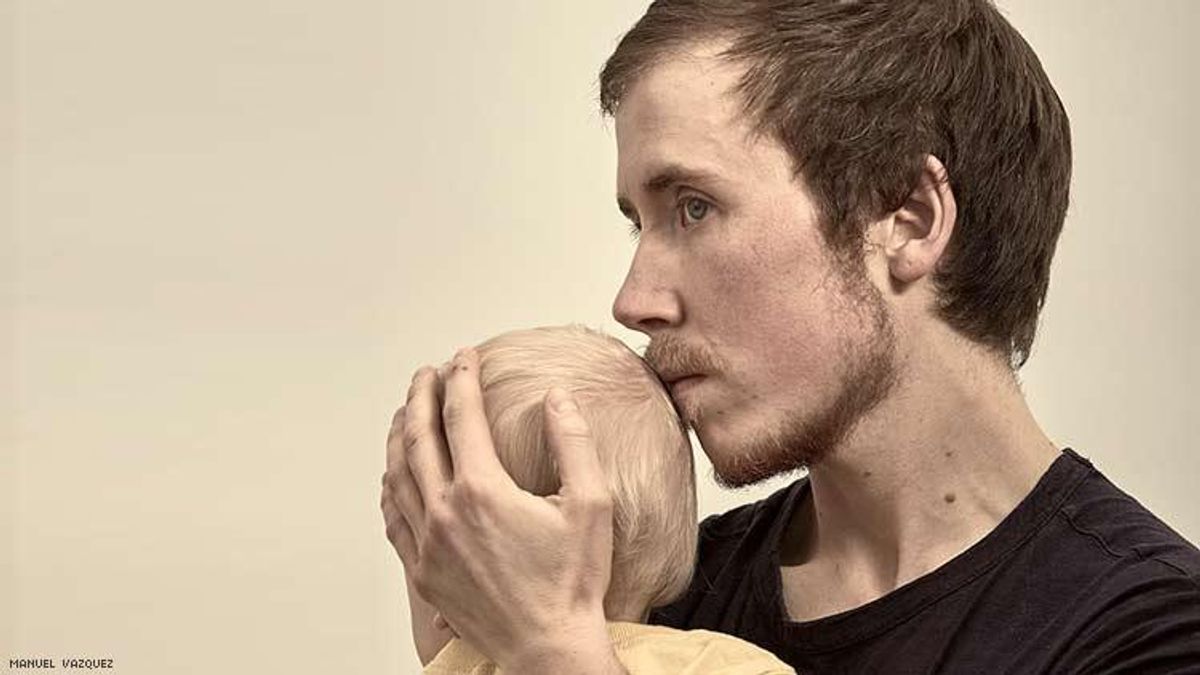

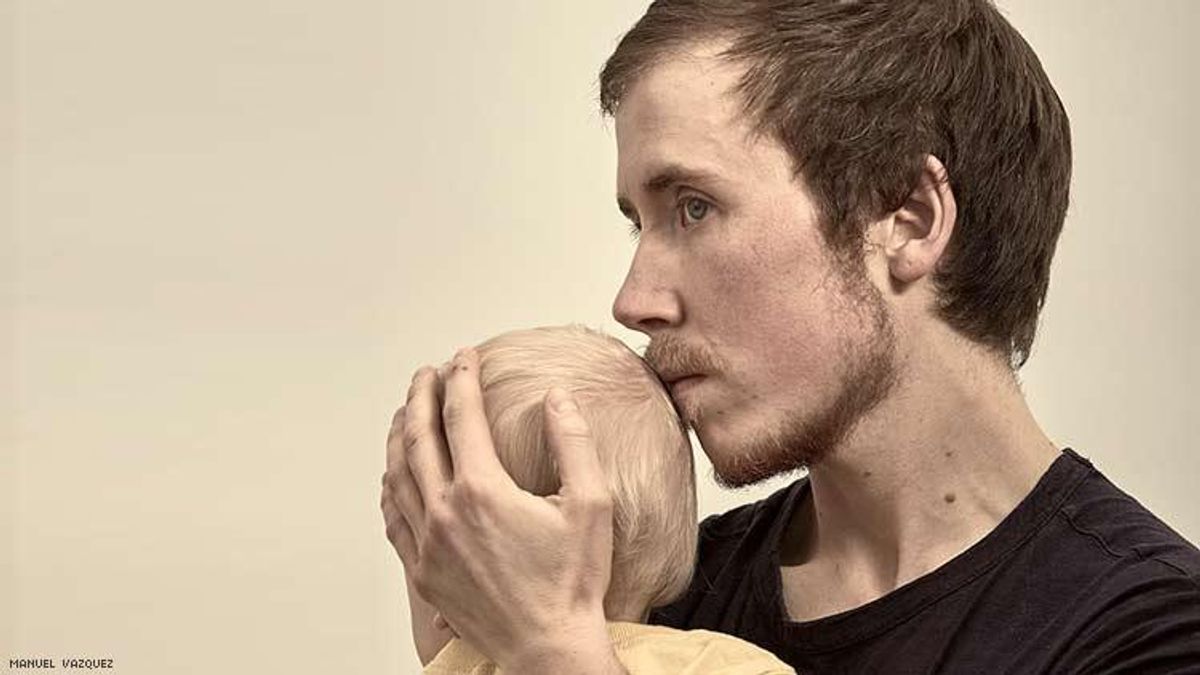

How And Why This Trans Man Carried And Gave Birth To His Own Child

Thanks to the documentary, ‘Seahorse,’ you can follow along.

April 28 2019 1:09 PM EST

April 28 2019 1:27 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Thanks to the documentary, ‘Seahorse,’ you can follow along.

"Finally, other people can see who I am."

These are the words Freddy McConnell uses in the documentary Seahorse, which premiered Saturday at the Tribeca Film Festival, recounting the early moments of his transition. Though a simple declaration, the way he expresses it, and how early in the film he says it, is the only signal I needed that this 89-minute journey would be worth it. Granted, the documentary's logline -- "Director Jeanie Finlay charts a transgender man's path to parenthood after he decides to carry his child himself." -- had me intrigued from the jump. But all too often, trans stories told by cis people result in sensational, half-baked narratives, so I was wary.

So, too, was McConnell, a journalist by trade, when he began seeking out filmmakers to document this part of his life almost four years ago.

"It was very important for me to find these people that I could trust because I've seen lots of trans stories being told before, and not being told particularly well the majority of the time I have to say," he tells Out. "And I've heard, frankly, horror stories from friends -- not that I had any fears of that happening because I just knew that I wouldn't let it."

Finlay is known as one of Britain's most distinctive documentarians with projects including ORION: The Man Who Would Be King, The Great Hip Hop Hoax, and Sound It Out. She also did Game of Thrones: The Last Watch, a doc about the making of the titan HBO series' final season that will air May 26.

With Seahorse, Finlay's created an intimate and revealing interrogation of masculinity and gender presentation through the eyes of a pregnant man. Tender and compassionate, the doc takes us on McConnell's emotional, (extra)ordinary journey to start a family. (In case you didn't know, the doc is named as such because seahorses are the only species in which males give birth to their offspring. Thus, trans men who give birth to children are called "seahorse dads.")

McConnell and Finlay spoke with Out just hours before the doc's premiere about the process of chronicling this experience. They discussed their lessons learned, the differences in being trans in England than in the United States, and what they hope others might take away from the film.

Freddy, talk to me a little bit about making the decision to not only start a family, but carry your child yourself.

McConnell: Firstly, I've always wanted to have kids. I've always wanted to have a family, as you say, not that I always wanted to be pregnant, but I always thought one day that I would be a parent. And then, in the U.K., when you want to medically transition you go to a clinic and there's kind of a particular pathway you're expected to follow. One of those things is that you basically sign a consent form to start testosterone, and within that consent form it talks about the fact that you will therefore be infertile. It doesn't give any detail or nuance or anything like that, it's just so you understand that you're kind of signing away your ability to have biological children.

I did that in my early 20s, and I just thought, "I'll figure that out at some point in the future, it doesn't feel particularly relevant right now." A few years passed and I'm thinking about my options and I saw on YouTube a couple of trans guys who were documenting their pregnancy, and it kind of blew my mind and it was exciting, but also really scary. I wasn't sure if I would feel able to do that or if I was allowed to do that... It was another good two years until I had come down on the side of thinking, "Well, this feels like the right thing for me to do. I have the right support networks in place. I live in a small town where I'm surrounded by friends and family. I have a good doctor." And my family members have talked to me about pregnancy and having children in a positive way, in a not-especially-gendered way, which is just my luck I suppose to have people like that around me.

And also, the other options [for starting a family] didn't seem any less difficult potentially. As a single, trans gay man pursuing adoption, I was very intimidated by that. I felt like I could be exposed to, you know, transphobia, and homophobia, and gatekeeping, and all sorts of things. So I just wanted to do something that I would feel more in control of.

Jeanie, Freddy mentioned how some of the stories that we've seen told, particularly about trans folks, have a tendency to either not be done well or to be salacious. What steps on your end did you take to help prevent that from happening?

Finlay: [This is a] film that we've made with Freddy, not about Freddy, and that was really, really important. I needed to have autonomy as the filmmaker, but I was always mindful of the tropes. We talked about it, and I didn't want to make a film where we would have Freddy holding a picture of him as a young person, like side by side, and then talking about his dead name... I wanted the film to feel domestic and ordinary, and amazing and extraordinary, and messy... I wanted to reflect the fact he is a life, not just be a tabloid headline, or something that was simplistic, because human beings are complex... I wanted to make a film with empathy and tenderness.

One of the things that stuck out to me about the documentary is, for you Freddy, as you are going through this process it seemed like, all of the medical professionals were very supportive and competent in trans-related healthcare. I'm not sure I can say the same of the U.S. healthcare system. Describe your experience.

McConnell: I want to acknowledge that my experience was unusual, I would say. Unusually positive. I think I got very lucky. Coming from a small town where I knew my midwife's residence -- she's a family friend -- I could be quite careful about who I did and didn't encounter along the way, because she formed a bit of a protective barrier for me. And I've heard lots of experiences from other trans men in the U.K., and trans people in general, that relates to the fact that their healthcare is not great and it has all the same problems that I think folks in the U.S. have. I should say, lots of stuff happened that isn't in the film -- that's the nature of a 90 minute documentary. And one of the things that happened was the doctor that I had seen for years reacted very badly to the idea that [I was] planning to carry my own child and then discharged me. That left me unable to access any kind of counseling or mental health support throughout the process.

I didn't really realize until after the fact how terrible that was. I did have one negative encounter when I went for one of my scans, but like I said, it was mostly very positive... I felt like I was very careful about how I presented myself and how I spoke. I was very conscious of that and that was stressful but that was just something I felt I had to do in order to stay safe and it kind of worked for me.

And I think it worked for me, in large part, because of my race, and my class, and other things like that. And my maleness. Even though I was going through pregnancy, I was definitely experiencing male privilege all the time. I want to acknowledge that for sure. So, I think it shouldn't be about luck, but I think it was to a large extent for me.

Jeanie, as the filmmaker, the person observing this entire process unfold, what did you learn?

Finlay: I learned so much. I've made films with large teams, with small teams, and I think one of the things I learned from this was to trust the process. It's really significant for me to trust what was going on -- to trust my own ability to find the best way to articulate the story. I think that that was really an interesting moment for me. Some of the films I've made have been more reconstructing things that happened in the past. So for me, it was certainly very interesting and exciting to be making a film in present tense, to observe the moment, and to be able to, you know, go for a run, and think about "What did we talk about today? And what was said?" And also, "What does it mean to be a man? And what is the dynamic between me and Freddy? What does my gender bring to this conversation? What does that look like?"

I think making films is about disruption, so in lots of ways it's a catalyst, and so hopefully we're both left with questions. The reason why I said "yes" to this film -- I say "no" to everything. I've said yes to Freddy and Game of Thrones and that is it in my life as a filmmaker -- is because I didn't know what was going to happen, but I was interested by the question, so that was important to me.

McConnell: The fact that Jeanie was interested with the unknowns, and also the parenthood aspect, that was important for me and, not necessarily what I was looking for, but the fact that my transness wasn't the main event I suppose, like right from the word "go," that resonated with me. Because I wanted to make a film about the unknowns, so that worked well.

Freddy, in the doc, you speak a number of times about how you think the conversation around gender, around bodies, around pregnancy, would be different if more men had the chance to experience being pregnant. What did you learn through the process that you think other men can stand to learn?

McConnell: I think it's for me more a case of realizing how little we talk about pregnancy in our culture, because it is usually an experience that women go through, 99.9 percent of the time. I just hadn't realized how true that was, and how shocking that would feel. There's all of these things that lots of people experience when they're pregnant, and it's not just that they're hardly talked about, I don't think that even most women who go through pregnancy know about it. It's so absent and that's shocking. If men went through it, it would be the subject of canonical literature. Right back as far as we were creating art and communicating, knowing about this experience, the upsides and the downsides, would just be something that you are aware of from the earliest moments of your awareness of anything.

I also struggled with the identification. I wanted to feel a part of a community, but I had to go online to find that. I did, and that was absolutely wonderful and I now have great friends through that, but to be in a room of women who have been pregnant sharing their stories, part of me was able to get something from that, but a bigger part of me found it very difficult because I did feel like my experience was different in quite important ways, and that was hard to talk about and hard to explain, obviously. And it's not that I think men in general could benefit from understanding what it's like to be pregnant, because I don't think that's particularly realistic -- in the same way that it's really probably not a good use of energy to try to explain to cis people what it's like to be trans -- and that's fine because as a dad who's given birth, that feels really special.

I was talking about this with another seahorse dad, it feels like a super power, and it's fine that it's really unique and rare, and that's just the way it is and that's not a bad thing and it's not a weak thing. It's just more about acknowledging the dynamic, the gender dynamic, and what it has meant for discussions of pregnancy, and awareness. It hit me like a ton of bricks. And it's not a very helpful observation for me to make as a man, that this thing that women experience generally doesn't ... "I didn't realize looking after a baby is really hard." Millions of people collectively groan.

So can I get an update on your child? How old is he now?

McConnell: He's doing really well, and life is really good, but it's kind of a different story that isn't one that we're telling right now... I feel like that's for him to decide when he's older if he wants to.

RELATED | This Doc Is A Worthy Tribute To A Los Angeles LGBTQ+ Icon