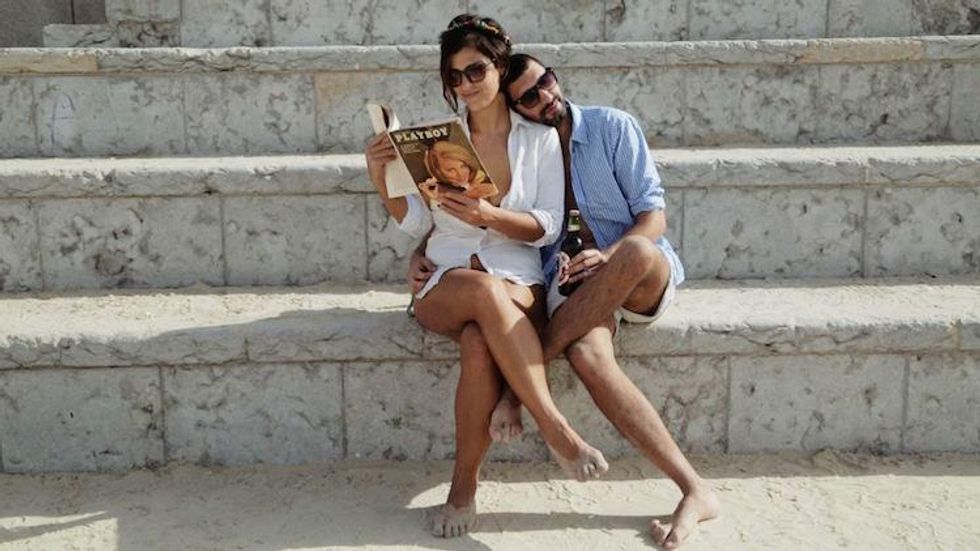

Photo (above) courtesy of Khader Abu-Seif, Jake Witzenfeld (left) and Khader Abu-Seif | All other photos courtesy of 'Oriented'

Within the wider discourse of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, that there are Israeli-Palestinians is a fact that often goes unnoticed and unappreciated. Here in America, we like to think of ourselves as a melting pot. But nowhere is that term more apropos, more tangible, than in the Middle Eastern country barely the size of New Jersey. For religious and political reasons, the narrow strip of land has always attracted a disparate array of visitors, but especially since the nation's founding in 1948, nobody's identity can be taken for granted in Israel. Israeli citizens can be Jewish or Arab; the Jews can be from Argentina, Spain, Russia, or Iraq; the Arabs can be Muslim or Christian, Palestinian, Bedouin, or Druze. In a society where so many cultures coexist in such close proximity, the questioning of one's own place, of how one fits in, or where one doesn't, is natural. It is the confusion that such probing elicits, arising from the confluences and conflicts of self-identity, that lies at the heart of Jake Witzenfeld's debut documentary, Oriented.

Over the course of 15 months, Witzenfeld, a straight, British Jew, followed a group of three gay Palestinians living in Tel Aviv: Khader Abu-Seif, Fadi Daeem, and Naeem Jiryes--a handful of the 1.7 million Arabs that make up roughly 20% of Israel's population. They hold Israeli passports, vote in Israeli elections, speak primarily in Hebrew, and yet they can't and won't call themselves Israeli, because they are Palestinian. Identifying with their stateless people, who live scattered mostly across the Occupied Territories, Syria, and Lebanon, theirs is a confused position, straddling societies, lying both within and without.

Ahead of the New York City premiere of Oriented at the Wythe Hotel in Williamsburg, Out sat down with Wiztenfeld and Abu-Seif. Over iced teas-turned-G&Ts, we discussed life as outsiders, rising tolerance within the Arab world, and what needs to be done to end the interminable stagnation of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process.

From left: Khader Abu-Seif, Naeem Jiryes, Fadi Daeem

Out: Where did the idea for Oriented come from?

Jake Witzenfeld: Well. I'd quit my job and was looking for a story. I saw a video clip of Qambuta Productions, this young collection of Palestinians making a point of gender politics in their own community. I thought it was so fresh and so new, and then I found out about Khader and his boyfriend [David, a Jewish Israeli], and I was curious about them--

Khader Abu-Seif: Ex-boyfriend.

JW: Sorry, ex-boyfriend. But I was curious about this video, and I was super curious about their relationship, and what Khader's perspective was--I felt like he would have had a vantage point, in a way, on the city. So we met up for a drink and got to talking.

KA: OK, do you want to hear how it really happened? Jake told me he really wanted to make this movie about our relationship--the Arab Palestinian activist and the Jewish Israeli producer--about our lives and how we handle all the things around us. And I looked at him and I said, 'Oh my God, that's so '90s. I have another proposal, let's do something on what's happening right now among young people, among the LGBTQ Palestinian society in Israel.' It only took a moment, and Jake was on it. He didn't have to think, it was just, 'Ok, let's figure about how we can do this.'

It's funny, in the beginning, I was sure that I would have a bigger part in this movie--no no, not in a diva way! Just, the cameras were following me so much. But when I watched the final cut, I was amazed. My friends are so strong, and their parts in the movie are so strong, and in that moment I knew I was right in telling Jake to make it about us all. Fadi says so many funny and stupid things, and he owns it all up to this day, and Naeem's story is really the the typical coming out story. And so, seeing the whole thing emerge, I thought to myself, My God, next to these guys, I'm so vanilla [he says, waving down a waiter in a vibrant magenta jumpsuit].

And the name Oriented?

JW: Came from a lot of grueling. From the beginning, it was always called 'The Misfits.' But then, over time, I realized that, not only is it a really overused title, but that it wasn't really what this film was about. It was about these people's identity, about not fitting in on several different levels. The spirit of the film that emerged was about them finding their direction, searching for their direction. 'Misfits' suggests victimization, it suggests otherhood and outcasts. 'Oriented,' on the other hand, suggests a transcending of that, I think. It's a more positive understanding, it's coming to terms with your identity.

KA: And, it's kind of like, turning a map in the right way. Plus, before they accuse us of Orientalism, of this British guy filming a bunch of Palestinians, we just went and put it in the title.

JW: Precisely. And, I think that 'Oriented' as a title also refers to the collaboration that was oriented between a straight British Jew and a bunch of gay Palestinian-Israelis. At the end of the day, I directed the movie, I took lead, but it was always about working together to depict their characters correctly.

Early on in the film, Khader, you're giving a talk at the LGBT Center in Tel Aviv, and you say that you want to introduce a new generation of Palestinians. What is this new generation?

KA: First off, I want to say that in Israel, when you ask someone where they are from, they will say Morocco, Iraq, Poland, and be really proud of their ancestors. But in the minute that you say Palestinian, they freak out. They cannot hear it. The minute you say Palestinian, you become their enemy. Speaking in that setting [LGBT Center in Tel Aviv], I just wanted to break the stigma of gay Palestinians. And you see in the movie the response I get was, 'Well, what do you want from us?' I say, 'I don't want anything, but you need to understand that I am a Palestinian living inside this country, and you need to respect that.' The most common response is for people to say, 'Oh, go to the Arab world and see how they treat you.' These Tel Avivian gays think they are the only ones who are openminded, and it's crazy to see how irritated they get when this compact Palestinian guy stands up and says, 'Hey, I am gay, I am open about it, and my family knows.' People expect Palestinian gays to have suffered because of it it--well, I haven't.

Why do you think things are changing now?

KA: We have been 60 years under occupation, and I think that people under occupation will take more time to develop. For example, there are people only 10 years older than me, who never thought about learning graphic design or something artistic. It was always the expectation that they would become a doctor or a lawyer, and today, the Palestinian generation has opened up to the artistic world, to singing, to dancing, to being gay. The generation before us didn't even have the ability to think about creating something bigger than themselves, creating a change in the perception of the world. This is a new generation, we have amazing bands that play against occupation, about sexuality, we have amazing artists--and I'm not talking about 20, I'm talking 10 years ago, it didn't exist.

Fadi Daeem in Amman

In America especially, when people think of the Arab world and gay people, they think of ISIS throwing people off buildings. But then there's that incredible scene of you all partying in Amman. Do you see a generational shift across the region?

KA: I can only enter Egypt and Jordan, because I have an Israeli passport, but I can tell you that in Amman, it's crazy. Right now, everything is open. They have great concerts and they have this amazing gay magazine--I think the scene is opening up. And Beirut. Beirut is crazy with gays and lesbians.

I think that people are really narrow minded when it comes to Arab culture. In Los Angeles, I was wearing a shirt with lyrics from a popular Arabic song on it, and the reaction was so ridiculous. I heard two gays like, 'Oh my god ISIS ha ha ha'--no no it's true! And then we were in this gay private member club or something, it felt like the gay Republican Party, and I hated every moment. Behind me there was kind of famous gay, and he was talking about how he had just come back from rehab, and everyone was clapping for him. And I was just like, How is this a problem? How is this challenge? He just came back from rehab--I wish that was the biggest problem I had, I wish I could see Arabic writing and immediately think, Oh haha ISIS. Not all Arabs are Muslim, and not all Arab culture is religious. The Arab world is opening up a lot right now, but nobody is going to tell the story of gay Palestinians. It has to be ISIS, the threat to Europe, to America.

JW: I just want to add that I think that it's incredibly irresponsible of the media and of storytellers not, at this moment, to be engaging with intersections between 'the West' and 'the other.' We need to smash this clash of civilizations bullshit narrative that is obviously being sustained for someone's own interest. Now is the time, because if we don't start blurring the lines and creating a global assimilation, the repercussions, I think, are going to be horrendous. If Europe and America, the godfathers of liberalism, don't open the door to engage with liberal people from other cultures, those people will eventually turn to the extremist factions within their own cultures, or they'll just do their own thing, but define it in opposition to Europe and the US. With the internet and cheap air travel, why are our attitudes the one thing lagging behind?

At one point, before filming your second video, you talk about how your national and sexual identities cannot be separated. Can you talk about that?

KA: Our first video was totally about sexuality. But it's all Arabic symbolism, so Arabic people get it right away, but people from the West couldn't really understand.

The bride and the groom are really sad, they don't want to get married. The guy who puts on the keffiyah, who represents the nation and strength, is in the front hugged by a woman in the niqab. The guy who's sitting in the back with the cigarette and wearing nothing, he's in the back because he doesn't matter. The two lesbians, of course, are separated, they cannot be next to each other. It's so amazing, because Arabs get it in a minute. They're like, boom, it's about gays and lesbians.

The second video, we made it during a difficult time [after the kidnapping and murder of the three Jewish teens, during the lead-up to the Gaza conflict], and a lot of Arab people were getting attacked. And I thought, Ok, we need to bring back our nationality, and Fadi said that we can't separate them, that they come together as a package. What evolved was a really amazing discussion of what the key symbol means, because it really is the symbol of Palestine. When people left their homes [in 1948], many kept the keys. And today, there are a lot of women who are passing them onto their sons, because there is this hope that they will go back home someday.

There were a lot of people who didn't like this video so much, because it was political, because it was dealing with the separation, but I think it's so important. Every time there's a war, this happens. I wish that all I had to fight for was my sexuality, like people in Germany or the United States. Most gays in the world, they are not living in these difficult places. To define myself just on my sexuality would be great, but I cannot. Every time there is a war, every time something happens politically, automatically, all I am is an Arab, the enemy. It's so frustrating. Fadi is right, the social and political cannot be separated.

One of the most intense, if understated, moments in the film was when the sirens were sounding in Tel Aviv. There you were, a Palestinian living in Tel Aviv, hearing the explosions of the Iron Dome intercepting rockets from Gaza... you must have had so many conflicting feelings.

KA: That was a really hard time. It was really extreme, really intense. At night, lots of right wing radicals would run past our apartment screaming, 'Death to the Arabs!" At a certain point, I said to David that I wanted to remove my last name from the mailbox. And David said, 'Never! What are you talking about? Never. Let them do what they will.' But when you're a minority, on the one hand, you understand why people are so irritated. They don't want to live their lives afraid [of rockets from Gaza, of kidnappings]. But from the other side, they aren't aware what they are doing. They aren't aware that they are terrorizing me, that they terrorize Arabs living inside Israel. It's crazy. It's exhausting. In this moment, you feel useless, and that you can do nothing to change it.

Do you feel hope for a future for Palestine, for peace?

KA: Hey, I'm still there. I think, inside of me, even though I'm still so tired and so sick of it, and every time I leave for a month or two weeks, I feel like this place is so small and I am so much bigger than it, it's my home. This is the only place I can really call home. This is my friends, my family... oh my god what is wrong with me, why am I crying in this interview? I never do it! Like, this is home, and sometimes you just need to try to change it no matter what. I want to change it, I want it to happen in my lifetime, but I don't think it will. I am the biggest believer that Jews and Arabs can work together, like look at us [he says, referring to Jake and himself], look at me and David. It's unreasonable that these people can actually live together, can be friends, can be partners, can work together, and yet not figure this out. I mean, we can love each other. I know it sounds really cliche, but it's happening. For four and a half years I was with a Jewish guy, and I'm not ashamed of it, I'm proud of it. If we can do that, we can live in peace together.

Nagham (left) and Fadi Daeem in Jaffa

Of course, there are still many who have difficulty spanning the divide between cultures pitted against each other for so long. In the film, there's that really incredible discussion between Fadi and Nagham at your sister's wedding. Fadi was feeling like a hypocrite for falling for a Jewish Israeli soldier, and Nagham's response was 'life is not just an ideology.' She then goes on to say: 'It's a fucked up world, we live in fucked up world. As Arabs, 1948 Arabs, Palestinians... no one knows where we belong, who we are and where we are going. It's a whole fucked up world, but it has nothing to do with love. So at least, have fun.'

KA: A lot of people thought that Jake wrote that for her, but he didn't.

JW: I couldn't believe it. When I got the translation back for that scene, I was just like, this is ridiculous. They're so emotionally intelligent it's insane. To be able to speak so objectively about your own identity, I think, speaks volumes about how much you think about it, how hard it is, how draining it is, constantly. But Nagham, she's an amazing woman.

So far, you've had screenings in the United Kingdom and Los Angeles--what have reactions been like?

JW: So good. We've been so lucky, and it's been quite universal, which is nice. I was very happy that we had a good population of Arabs at both. In the UK we had a Jordanian girl, a woman from Gaza, and a couple of Israelis. And then in L.A. we had a Lebanese guy and a gay American Palestinian--and those are the moments for us where we're just like, wow.

KA: The second screening in L.A., that was was the time I cried. Like, I died on the stage, I couldn't speak. Because, from the beginning, I always told Jake that I want just one gay Palestinian to watch this. And at the end of the movie, there was this guy sitting in the crowd, and he said, 'I don't have any questions, but I want to tell you that, I'm American, and I'm gay, and watching this movie, this is the first time that I'm also proud to say that I'm Palestinian.' And I was like, [wiping his hands] bye. Because for me, this was the purpose. For me, it was always to represent Palestine, it was to represent the LGBTQs inside of Palestine. And without him [he says, referring to Jake], I could never have experienced it.

You've not showed this film in Israel yet, but looking forward, what are your hopes for Oriented?

JW: You know, since my time at Cambridge, I've been trying to find a place for this kind of dialogue. I ran the Israel Society, and we co-curated this week of discussions between Israeli and Palestinian speakers. And then four days before the event, the Palestinian Society decided to pull out of our event and hold an Israel Apartheid week on campus. The irony is, I had to go to Tel Aviv-Jaffa, away from those middle class white boys from Surrey thinking they're doing good in the name of Palestine by sustaining this stark narrative, I actually had to come to the heart of the conflict in order to find people that I can have a genuine, open conversation with.

Whenever people consume content about Israel-Palestine, they immediately expect this stark black-and-white. That's what people are comfortable with, right? 'I am Jewish and I think this' or 'I am Palestinian and I think this.' People are so emotional about this. It is, I think, the most loaded conflict globally, and that's the problem. If it was as fucking simple as a two-sided, dichotomous argument, we'd have solved it by now. So, maybe there's a lot more paradox and complexity than that. I think what's so amazing is that, with this film, we managed to create a gray space. I want people to be confused, to question what they had believed and question what this film has made them come to believe. This film is about Palestinians, but we're not asking our audience to pick sides; we're just sharing their reality, their lives. I don't think an Israeli Jew could have made this film. I think that's the special thing about the relationship behind Oriented. Like Khader, I was an outsider.

Everything that we've been talking about, I feel, is something you've probably already felt, and I think this film really addresses those feelings. I hope that this movie, both outside of Israel and within, validates opinions and questions people might have thought were taboo. And for those who aren't into this, for people who hold these close-minded, dogmatic beliefs, I want Oriented to be the mouthpiece of shut the fuck up--through kindness, of course, by melting these hardened beliefs with portrayals of very human experiences. Beneath it all, I want Oriented to be the kick in the knees that gets people talking, because we need it.

For more information, and to learn about upcoming screenings, visit their website. Watch the trailer below:

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays