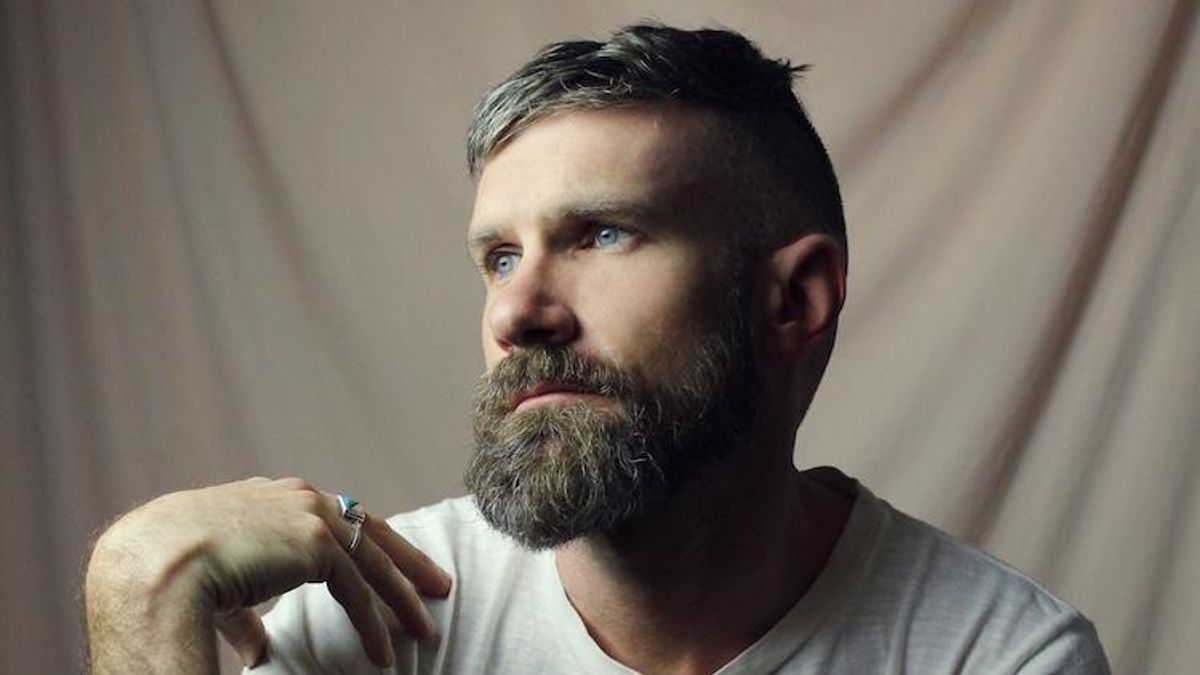

Queer Brooklyn/ Seattle-based dearm-folk quartet Tenderfoot first captured our attention with their soft, melancholy album Red Coat. Today, the band has announced that their back with a new record, Break Apart, out February 2 via Porchlight Records.

Coinciding with the big news, Tenderfoot today drops the title track from the album, and if it's any indication of what we can expect from the rest of the LP, we're in for a delightfully folk-rock soundtrack to our winter that's somehow simultaneously mournful and resiliently hopeful.

"Break Apart is about the painful process of disentangling from all of the forces (real and imagined) that tell us we are doing great, or that we are failing," explained lead singer-songwriter Adam Kendall Woods in our exclusive interview. "I think especially as queers, we live these faceted lives where we are hungry for acceptance. Maybe it's easier now for some folks to come out to their family and friends and take steps towards a truer identity, but then they enter these social constructs of what it means to be a f****t, or queer, or butch, or femme, or an artist or a successful person. I'm getting closer to being able to define my own facets of existence, and writing this song was part of that process."

Woods is joined in Tenderfoot by Jude Miqueli (drums), Gabriel Molinaro (keys), and Darcey Zoller (strings).

"We've moved all over the city to different practice spaces, made vision boards together, smoked out and skinny dipped on warm summer nights, cried together over break-ups and health scares and lost loved ones," Woods explains. "They are definitely my musical family."

Take a listen to "Break Apart" below, then read our revealing interview with Woods about heartbreak, forming a queer family, writing from an honest place, and the social constructs of queerness.

OUT: Can you walk me through the story behind writing "Break Apart"?

Woods: Break Apart started out as more of a verbal realization than a song. I didn't know it at the time, but I was in the middle of a codependent relationship. After a fight over the phone one night, I took a bath and lit a candle and just started humming and singing notes like I usually do in the tub. The first verse came to me almost entirely intact: "I lost the part that always told me that everything is gonna be OK." That's exactly what it felt like in my life at that time. I jumped out of the bath and grabbed my guitar and the song was fully written in an hour or so. I recorded it on my phone immediately and sent it to the rest of the band, mostly as a way to just share with my family what I was going through. The song felt so explicit. They really liked it and we started arranging and shaping it that week at practice.

You've said it's about "the amount of power we put in other people's hands to make our dreams come true or to destroy them." Can any of you elaborate on that concept a bit more?

I think a lot about agency and choice in my life, and how I've given it up at different points with different partners. The idea of "breaking apart" though, isn't just in the sense of a breakup, or a removal of oneself from an unhealthy situation, as much as an unfastening from the cultural norms of love and power. The relationship you have to your life, your relationship to your own creativity. We all wait for a gatekeeper or a leader to allow us to do what we know we want to do anyways. We passively ask for permission from someone else. Break Apart is about the painful process of disentangling from all of the forces (real and imagined) that tell us we are doing great, or that we are failing. I think especially as queers, we live these faceted lives where we are hungry for acceptance. Maybe it's easier now for some folks to come out to their family and friends and take steps towards a truer identity, but then they enter these social constructs of what it means to be a f****t, or queer, or butch, or femme, or an artist or a successful person. I'm getting closer to being able to define my own facets of existence, and writing this song was part of that process.

You were in a relationship, on the road, and ended up in Seattle, where you met Jude, Gabriel, and Darcey. How did each of these meetings go, and how did the band ultimately come into formation?

Seattle is a small city, relatively speaking, and the art and music scene is even smaller. If you are a queer person creating things and searching for companions, you eventually meet every other person looking for the same thing. It's a really fertile city in that regard. The first year I lived there I just wrote songs in my bedroom all the time. I finally got a job as a barista at Stumptown, which opened me up to a whole world of creatives and also got me out of my room. I met Gabe at a barista competition and we hit it off immediately. He's the longest running member of Tenderfoot, and my musical brother in a lot of ways. He's a songwriter as well, under the name Health & Wellness, so we send bits of new songs back and forth, or make mad libs out of our lyrics when we need help filling in the blanks. He can play almost any instrument, and has been integral to Tenderfoot's sound and evolution along the way. His style is intuitive and spare and he can really identify what a song does and doesn't need.

Jude, our drummer, has been in almost every rad queer band in Seattle since I moved there. I met her when we shared a bill at Pony, which is an awesome queer bar in Seattle. She was in a band at the time called Wishbeard and I had a crush on every single member in that band. We became friends and admirers of each other's work and then one night, at her partner's birthday party (which was a Smashing Pumpkins themed party where I dressed up like an ice cream man and sang Disarm) we started jamming in her backyard. I had been working on some newer song pieces and she knew just what to do with them rhythmically. I looked up at her and was like "Do you want..." and before I could even finish asking her to be in the band she said "Yes!". We used to joke that I was band Mom and she was band Dad. We even had a joke band for a minute called Mom & Dad. She's in a new project now called Moon Palace that is exceptional.

Darcey, our cello player, literally walked up to me after a performance at a house show and said "I want to be in your band". At the time I was already playing with a violin player, and wasn't sure about having another string instrument in the project. Her energy and style was awesome though, and we kept tabs on each other for awhile. A year later after my violin player moved on to focus on her solo project I called up Darcey and she was still on board. Darcey's cello timbre is like a weathered singing voice and I oftentimes feel like I'm in a duet with her on stage.

This version of Tenderfoot has been together for about 3 years. We've moved all over the city to different practice spaces, made vision boards together, smoked out and skinny dipped on warm summer nights, cried together over break-ups and health scares and lost loved ones. They are definitely my musical family. When I made the decision to relocate to Brooklyn, it was really tough. But we're working out the bi-coastal relationship.

Sonically and thematically, how is this new album different from your first?

My first album Red Coat was very spare. All of the songs were recorded in one day, and then my recording engineer Aaron Schroeder and I pulled friends in to play and sing different pieces here and there. I didn't have a band to support the songs yet. The album reflects the year I spent on the road with my partner. I wrote songs to encourage and inspire us to keep going, songs during troubled times along the trip, and I wrote a lot of songs lamenting the relationship after we broke up. The album is very insulated in that way. I was listening to a lot of sad folky love songs back then, and I think you can hear that reflected back, but in a queer idiom. I wanted to encapsulate the intensity of the trip, this person that I loved, and all of my evolving feelings about relationships into those songs.

Break Apart was entirely different. It was extremely collaborative and benefited from years of accretion. We recorded slowly for over a year, workshopping songs during practice and at performances until they felt ready and then bringing them in to Aaron. I wanted to get away from myself for a lot of the content and just feel a part of a band, so a few of the songs on the album were created by recording jam sessions and structuring the pieces we liked and adding lyrics later. We'd get stoned and listen to Laurie Anderson's "O Superman" and then see what we would make afterwards. I started listening to almost exclusively women and queer artists and felt inspired by the experimental sound shifts of artists like Grouper, Angel Olsen, St. Vincent and Lower Dens. I was interested in creating an album that wasn't just lyrically-driven, but also had an intentional sonic texture.

Break Apart felt like the perfect overarching title for the album once it was finished, since we were pushing our sound further away from straightforward folk.

What about the recording process? In terms of location/ collaborations/ producers, how is this album different from your last?

We basically adopted Aaron Schroeder of Pierced Ears, our engineer and producer, into the band. We sent him demos and laid down tracks in pieces and really pushed everything. I knew I wanted soundscapes in a lot of the songs, and Aaron helped create those. He would tweak ambient sounds from a demo, like a truck passing by, or the band laughing after a false start, and weave them throughout the songs. He worked to push my voice till I would be screaming or almost whispering. In the studio, he would make us all play our parts over and over again and encouraged us to mess up or try new things on the fly. He was gleaning all of the pieces he wanted for his collages.

We recorded the album in a few different studios in Seattle, some famous ones like Hall of Justice and Laundry Room, and some friends' live-work spaces we rented because the timing was right. Aaron had his own studio called BLDGS but was priced out as Seattle started to draw more tech folks into that part of town. Two of the songs from the album were recorded there as well, and you can hear some of the grit of the cranes outside working on all the new condo construction. We wanted to keep some of it in there, treat it like documentation of space and time and sound instead of just a pristine recording. The razing of our neighborhoods was hard to witness, and it feels like one of the thematic backdrops to the album.

Can we expect more in the vein of "Break Apart" on the new album, or is it a more eclectic record?

The album feels diverse. There's a solo piano ballad on there called "Other Side Of Love" and a garage rock song called "PALMS." There's also a trippy instrumental called "Getting There" that's pretty impressionistic. But also some straight-ahead narrative songs that are akin to the writing style of Red Coat: songs about getting older and acknowledging death, songs about addiction, songs about losing love but having hope. I like to think of the album as just long enough. There were some songs that didn't make the cut, but these ones really earned their place in the constellation. The single "Break Apart" definitely feels like that center star though, connecting to all of the other songs both thematically and sonically. A little bit of every track on the album exists inside that one song.

Did 'The White Lotus' waste Lisa's acting debut?