As the Silver Screen's New Leading Man

September 12 2013 9:39 AM EST

May 01 2018 11:43 PM EST

aaronhicklin

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

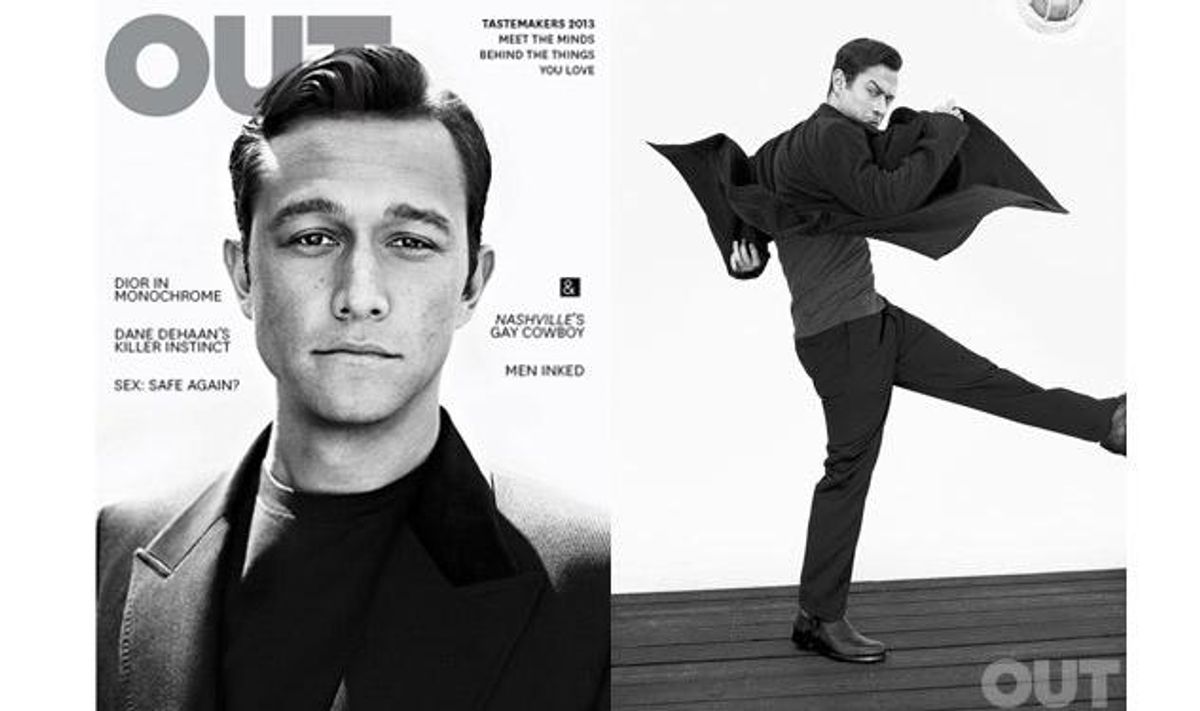

Photography by Kai Z Feng | Styling by Grant Woolhead

Watching Joseph Gordon-Levitt's short movie Pictures of Assholes is deeply instructive. In a virtuoso example of table-turning, the young actor channels his camera on the paparazzi that are hounding him and a friend in New York City. When Gordon-Levitt politely asks their names, they bristle with injury and insult, responding with "Asshole" and "Asshole Jr." Gordon-Levitt is undeterred, politely interrogating them as they pile insult on insult. Finally, the younger paparazzo comes clean about their motive: "We saw a young star with another guy, and it's implied that there's something going on," he says coyly. "The whole gay thing -- it intrigues people."

Contrary to many celebrity-paparazzi encounters, no punches are thrown, no voices raised. Gordon-Levitt does not even bother refuting the gay innuendo ("That would be really tacky--they would win if I had to clarify," he says). Instead, the video--which has been viewed more than 1,000,000 times on YouTube -- wraps up with a polite handshake as the men separate. For budding Justin Biebers everywhere, it's a textbook example of how to disarm your enemy without making a fool of yourself.

Pictures of Assholes, now almost a decade old, tells us a lot about Gordon-Levitt's feistiness and creativity, but most of all it illuminates his complicated relationship with his own celebrity. Many people -- like those entitled paparazzi -- have mistaken his ambivalence to fame as the hallmark of a spoilsport; in a world in which celebrity is currency, the famous person who doesn't want to play ball, who insists on boundaries, can feel like a slap in the face. But for Gordon-Levitt, it's always been about self-preservation.

"It comes from a really young age," he concedes. "It can be really awkward and difficult to be thought of as this thing on TV. Before understanding it or being able to analyze it, I just knew it made me really anxious." Regularly recognized in his teens as "that kid from 3rd Rock From the Sun," his reflexive response was denial. "I wouldn't just say 'No,' " he recalls. "I was way more convincing than that. I would first act confused, and then I would try to understand what they were saying. I would play the part."

Gordon-Levitt is a little more sanguine about his fame today. He even manages a gracious smile when a woman approaches our table at a cafe in Atwater Village, Los Angeles, to press a folded scrap of paper in to his hand. "I almost never lie anymore," he says. "I've learned that it's not useful at all, and it actually just exacerbates the situation." He's also learned to distinguish between people who connect to him through his craft -- "love that" -- and those who are interested only in his celebrity -- "a word that makes my skin crawl."

SLIDESHOW: Joseph Gordon-Levitt Up Close

Obviously, then, we are here today to talk about the former, starting with his new movie, Don Jon, which Gordon-Levitt wrote, directed, and stars in, and which might as well be subtitled Pictures of Assholes 2. Although very different from the guerilla style of that earlier film and leavened with whip-smart dialogue and funny, energetic performances from Scarlett Johansson, Tony Danza, and a mesmerizing Julianne Moore, it's fueled by a similar critique of a society that struggles to see beyond arbitrary labels.

Gordon-Levitt plays Jon Martello Jr., a New Jersey knucklehead and porn addict struggling to make real life match the expectations set by his X-rated pastime. Even a bombshell like Johansson's Barbara Sugarman can't manage that -- but then she has her own issues, trying to turn Jon into a cipher for her own hopelessly romantic ideals. Both are on a merry-go-round of perpetual disappointment.

Gay men steeped in a culture of Grindr and Xtube will undoubtedly find parallels to their lives in Jon's compulsion, but Don Jon is only superficially about porn. "I wasn't interested in making a movie about pornography," Gordon-Levitt says. "I was interested in making a movie about how people treat each other like things, and all kinds of media can contribute to that." In that sense, Don Jon can be viewed as an allegory for the way Gordon-Levitt has sometimes felt defined by his own celebrity. "I've been working as an actor since I was a little kid, and I've always been fascinated, and a little horrified, by the way people relate to images they see on screen," he says. "Sometimes I feel I am seen as a thing more than a person, and I don't think that's unique to actors. I think everyone is subject to that kind of pigeonholing."

Before our meeting, I had been warned by an editor at another magazine that Gordon-Levitt could be a diffident, reluctant subject, but it turns out not to be true. He is thoughtful and considered, and takes his work seriously. You get the feeling there is another, more playful Gordon-Levitt lurking beneath the surface -- the one who likes to pal around with the boisterous Channing Tatum and turn stalker on the paparazzi -- but it's not a version he wheels out for just anyone, and that's fine.

"He is not an emotional lightweight by any stretch of the imagination, which I think is delightful to find in someone in Hollywood," says Moore. She recalls being sent the script with a warning that it was about porn. "I took a deep breath and said, 'Okaaaay,' and started to read it. I was on a plane next to my husband, and I looked up and said, 'This isn't about porn!' I thought it was going to be salacious, provocative, prurient, whatever, and it's none of those things. It's an amazing meditation on what it means to be alive, and to be truly intimate, and to live without any expectation of who you think you should be."

It's also a movie about grief. Moore's character, Esther, is a widow whose loss is all too palpable. "For those of us who've experienced extreme and sudden loss, I feel like it's sometimes offensive how it's depicted in movies, because there's always an expectation that by the end of the movie everyone will be healing," says Moore, whose own mother died unexpectedly four years ago. She describes Don Jon as "the most honest depiction of grief in a film ever." There's good reason for that. Gordon-Levitt's older brother, Dan, died in 2010, apparently of a drug overdose, and it's clear that his absence is keenly felt.

When the subject of his brother comes up, Gordon-Levitt talks about him freely and tenderly, crediting Dan as the guiding spirit behind hitRECord, a website the two brothers launched in 2005, initially as a space to host their own projects and then as a place for anyone and everyone to contribute creatively.

"He was so overwhelmingly positive and warm," says Gordon-Levitt. "One of my favorite things about hitRECord is how positive it is, especially compared to most of what goes on on the Internet, which can be snarky and cynical. I credit Dan with that. He couldn't help but get swept up in it, and it makes me so happy that the momentum continues today. I'm on the site every day, and the fact there's this warmth to it, it reminds me of him every time."

I'd read that Dan was a fire-spinner, and wondered if the two brothers had inherited a free-spirited, free-thinking outlook from their left-wing Jewish parents, Jane Gordon and Dennis Levitt. They met while working at KPFK, a donor-funded radio station in California liberal enough to have received a copy of the Patty Hearst tapes from the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974. Gordon ran for Congress for California in 1970 on the Peace and Freedom ticket, and Levitt dallied with anarchy in his youth ("My dad never blew anything up, but he probably had friends who did," Gordon-Levitt once told a reporter from The New York Times). Gordon-Levitt's grandfather, Michael Gordon, had been a successful Hollywood director until he was blacklisted during the McCarthy trials in 1951, a calumny that must have shaped the family's attitudes to mainstream media and the entertainment industry.

"I think they both instilled into me and my brother the feeling that we're part of the world, and that that's important -- that we're all connected and everyone's well-being is tied to each other," says Gordon-Levitt. "They're hippies, but they were not so much about being flower children as getting something done, trying to stop this war, or changing civil rights or the feminist movement -- and they still are that way."

Today, hitRECord is a full-time operation that Gordon-Levitt describes as a direct expression of his brother's personal transformation from an "introverted and sort of shy dude and a computer programmer by trade... into this extremely extroverted, swashbuckling superhero and artist." Recalling his brother's favorite book, Dr. Seuss's Green Eggs and Ham, his elastic features break into a smile. "You know, 'Try it!' " he says, paraphrasing the book's imperative. "That was what Dan was all about. We tend to pigeonhole each other and pigeonhole ourselves and believe that 'Oh, I'm not that kind of person.' When Dan first saw people fire-spinning he didn't think he could do it, but eventually he tried it, and it had such a huge impact on him."

Easy as it is to forget in the light of the career he has built for himself, Gordon-Levitt went through his own transformation after 3rd Rock, taking time out to study French at Columbia University before landing a role in Gregg Araki's Mysterious Skin, the film that first broadcast the actor's post-3rd Rock intentions. As Neil McCormick, a young gay hustler in denial about the sexual abuse he was subjected to as a child, he was bewitching to watch, not least for the way he balanced vulnerability and imperviousness. "At that point, I so badly wanted to act in a really good movie, in a really creative, challenging role that I could sink my teeth into," says Gordon-Levitt. "I auditioned for lots of little movies and no one wanted to put me in their creatively challenging roles because they didn't think I could do it. And I don't blame them. I was known for being on a farcical television show."

For those familiar with him as an alien in a boy's body, his metamorphosis into a hard-boiled, languid cock tease was a revelation that put him at the vanguard of a new generation of young actors willing to take risks in return for creative reward. Other movies soon followed, including the noir-ish cult fave Brick, the crime film The Lookout, Kimberly Peirce's Iraq drama Stop-Loss, and the romantic comedy (500) Days of Summer. "It was really interesting to watch Joe's transformation, literally blossoming into a movie star as people took notice after Mysterious Skin," says Araki, who remembers Gordon-Levitt flying to Kansas on his own dime to study the local accent. "He's a very serious and very thorough actor, and has always been that way."

It's clear that Gordon-Levitt does not do things by half measures. Jared Geller, a partner on hitRECord and Gordon-Levitt's companion the night he turned his camera on the paparazzi, recalls introducing him to the renowned Russian clown Slava Polunin, whose show, Slava's Snowshow, he had produced off-Broadway. Gordon-Levitt was so impressed that he ended up training as a clown under Polunin and his son, Vanya. "He trained for years," says Geller. "It's not like he was training on stage -- he would get into the makeup and do the physical stuff offstage for years before Slava invited him to perform onstage with an audience. It was a really beautiful teacher-student relationship to watch."

That relationship flourishes on hitRECord, albeit with Gordon-Levitt in the mentor role. To listen to him talking about the possibilities of social media and the web is to marvel at his faith in the digital age's ability to bring us all closer. Has he read Sherry Turkle's Alone Together, in which the MIT professor dialed back some of her original enthusiasm for technology, arguing that it was shrinking attention spans and creating a false sense of intimacy? He has not. "I'll be honest, I rarely finish books anymore," he confesses. "Usually, I'll read a book until I've gotten what I need to get out of it, and I won't finish it. I like short fiction better."

But he makes a cogent and compelling argument for why the anonymity of the web can foster greater intimacy, not least because "you're purely connecting to the thing they created--you don't know what that person looks like, you don't know if they are male or female, you don't know how old they are." Last spring it was announced that hitRECord would reinvent the variety show format for the newly launched cable channel Pivot TV, drawing on content from the site, with Gordon-Levitt as compere. If it works, it will represent a whole new way of creating and sourcing television content.

Of course, whether hitRECord would be the draw it is without the celebrity cachet that Gordon-Levitt brings to the table is another matter. "When confronted with this terrible beast of celebrity, instead of running from it, he decided to see if he could actually tame it and get it to do his will," says Rian Johnson, who directed Gordon-Levitt in Brick, as well as the 2012 sci-fi thriller Looper. "He tried to harness it, as opposed to rejecting it, and to see him create this force of good out of hitRECord, using celebrity as its engine, I really find fascinating."

It's one irony that the unwilling cast of Pictures of Assholes might appreciate. Odd as it may seem, the wide arc of Gordon-Levitt's adult career, fueled by his restless quest for authenticity and connection, owes much to them.