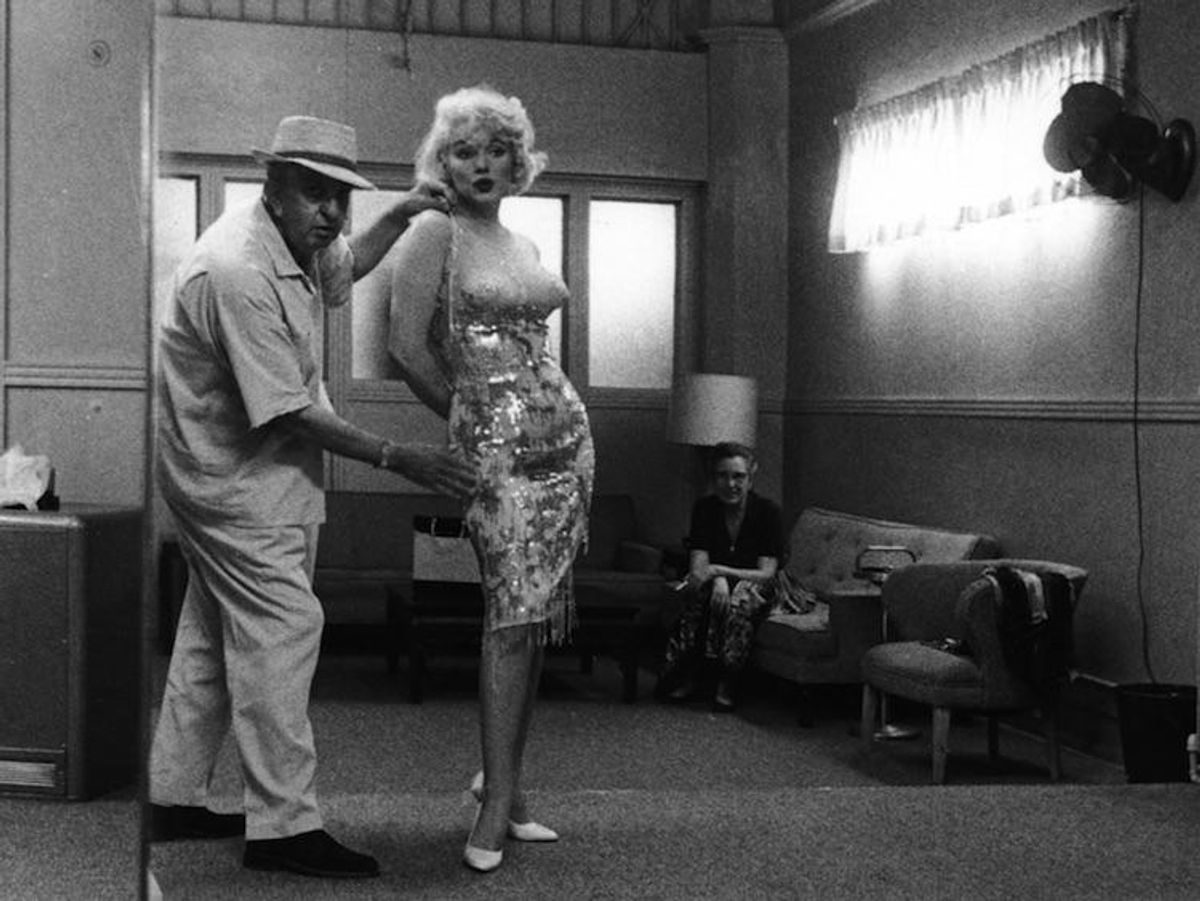

Kelly fitting Marilyn Monroe for 'Some Like It Hot' | Photographer Unknown

How is it that the genius behind Ingrid Bergman's jet-set noir in Casablanca (1942), Bette Davis' dowdy to demure transformation in Now Voyager (1948), and Marilyn Monroe's strategically tightened, nude dress that offended all of Middle America in Some Like it Hot (1959) is practically anonymous?

Australian filmmaker Gillian Armstrong answers this question in Women He's Undressed, which screens Sunday, November 15 as part of the DOC NYC film festival. The documentary traces the prolific career of enigmatic costume designer Orry-Kelly (nee Orry George Kelly) and his hidden life as a gay man in homophobic golden age Hollywood.

"I couldn't believe that this man's extraordinary body of work had been overlooked," Armstrong tells Out. "He had such immense talent, and I became interested in exploring what it was that made it possible for him to succeed in that particular time in Hollywood."

Kelly's career began as a tailor after arriving in New York City from his hometown of Kiama, an off-the-radar surf village in Australia. Abridging his moniker to "Orry-Kelly," he climbed the social ladder going to Greenwich Village speakeasies and nightclubs during the 1920s, and eventually met Archie Leach (better known as Cary Grant). The film traces their tumultuous relationship as roommates and rumored lovers.

The documentary is informed by representations of Orry-Kelly in his early interviews in which he gave no indication of his sexual orientation due to his careful discretion and "hetero" hobbies.

"Writers were amazed that he liked to go to fights, and he had a sort of rugged look - a slightly broken nose, and in interviews, writers would say that he doesn't look like a costume designer, but a director or architect," Armstrong says.

After moving with Grant to Hollywood in the 1930's, Orry-Kelly found success fashioning the careers of then unknown actresses like Kay Francis, Dolores del Rio, and Katherine Hepburn with intricate craftsmanship and painstaking attention to detail. Grant followed his own trajectory as a leading actor, lauded for his embodiment of ideal masculinity.

"During this time, gay men specifically were portrayed unfairly, as lesser than and as jokes for so many years in cinema," explains Armstrong. "There was such a pressure to conform to what was considered an ordinary, normal life," Armstrong says referring to Grant's highly public failed marriages to women. "Orry refused to hide his sexuality with a fake marriage. He had such a great sense of personal integrity, and we wanted to capture that sense of bravery in the film."

The biopic takes liberties with flamboyant, surreal-looking enactments, drawing from Orry-Kelly's posthumously published autobiography (Women I've Undressed) and letters to his mother. In interviews, surviving muses Jane Fonda and Angela Lansbury reminisce on his acerbic proclivities on film sets (on the set of Some Like it Hot, he told Marilyn Monroe that Tony Curtis had a better ass than her).

Women He's Undressed features spectacular clips of Orry-Kelly's Oscar-winning work, from Ava Gardner's Grecian gown in her breakthrough role in One Touch of Venus (1948) to Shirley MacLaine's lacey, Fellini-esque negligees she dons as a Paris prostitute in Irma La Douce (1963).

Women He's Undressed is as much about Orry-Kelly as it is fashion in film.

"I'm a huge fan of costume design and history," Armstrong explains. "The art of costume design is underrated. This is about Orry and his life, but I also wanted to give a greater understanding of how much genius goes into great costume design," says Armstrong.

Orry-Kelly's work made a lasting impression in both black-and-white and Technicolor. During the height of his career, actresses requested him by name. Armstrong says that it was his unprecedented talent and commitment to authenticity and sophistication that cemented his friendships with Hollywood's monolithic starlets.

"Since Orry came from a theatre background it was always about the story and what was right for the character," Armstrong says.

Armstrong outfitted Bette Davis for over 30 films, including Jezebel (1938) and The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939).

"He didn't dress her up and paint her as a sexual icon," said Armstrong. "He supported the fact that she wanted a sense of authenticity and historical accuracy."

Orry-Kelly went on to win five Oscars for best costume design, holding the title of most decorated Australian costume designer until 2014. Struggling for much of his life with alcoholism, in 1964 Kelly died of liver cancer in Los Angeles. He had a star-studded funeral (Grant was a pallbearer), but he had no surviving relatives. Orry-Kelly's awards and other film effects were archived

Women He's Undressed is a testament to the designer's forgotten influence on cinema, and 51 years after his death, he finally receives the acknowledgment he merits.

Women He's Undressed screens as part of the DOC NYC festival Nov. 15 at 9:15 p.m. at the SVA Theatre, NYC. Watch the trailer below: