Browsing in a secondhand-DVD shop in London, I found my fingers straying into the "epic" section, something they normally don't do. As a boy I loved Spartacus and The Ten Commandments, but a taste for epic cinema did not survive puberty. Yet who can resist a title like Waterloo? I didn't recall any such film ever having been made, and so I pulled the case from its shelf and turned it over. What I read there decided me; I bought it.

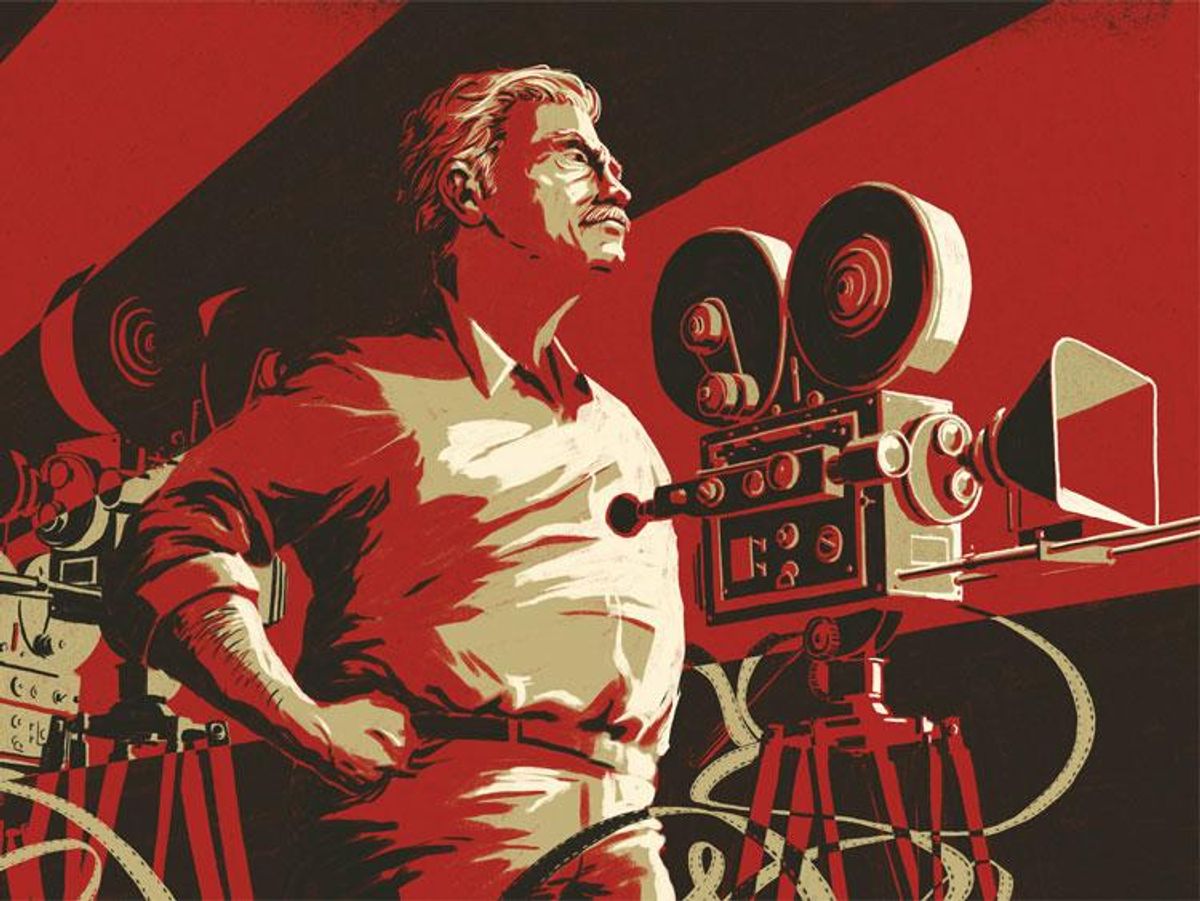

For on the reverse I'd seen a name whose romantic contours took me straight back to a snowy morning in early December 1991 when a black car had arrived in the slush to collect me from the Savoy Hotel in Moscow. That name was Sergei Bondarchiuk. In transliteration the i is usually omitted from his surname these days, but it shouldn't be; the last syllable is pronounced "chyook," not "chuck." You won't come across many people who can say they've met Bondarchiuk, and few would realize it if they had, because he wasn't known in the West. Even in the Soviet Union his career was an on-off affair, dependent on the capricious flatulence of Communist Party winds.

Yet both his life and work have something of the heroic sentimentalism of The Lord of the Rings and the colossal outlandishness of Gormenghast. Official sources tell us that Bondarchiuk was born in 1920 in Bilozerka, in what is now the Kherson oblast, Ukraine, and spent his childhood in the cities of Yeysk and Taganrog. He was discharged from the Red Army in 1946, took to the stage as an escape, and greatly distinguished himself in Shakespeare. At the age of 32, he became the youngest actor to receive the People's Artist of the USSR medal, and in 1959 he directed and starred in his first film, The Destiny of a Man, about a soldier fleeing from a Nazi concentration camp and returning home to find his family members killed.

Bondarchiuk mysteriously doesn't resurface for many years, and the reason, it turns out, is that he's directing the Russian War and Peace. And again, starring in it. It took seven years to make and was nearly nine hours long: a wobbly monster. In 1969, it won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film on stamina alone -- Hollywood's favorite epic, Gone With the Wind, is cabaret in comparison. Having learned to manipulate a cast of thousands, plus manifold explosions, Bondarchiuk tossed off Waterloo (1970) in a mere year or two. It was his first attempt at directing an English-language film, and it flopped.

His second English-language film, And Quiet Flows the Don, was over 20 years later, and this was the reason I'd come to Russia. After a snow-dabbed spin along the massive boulevards of the city, the driver put me down at the Mosfilm studio, an astonishing spectacle in itself. I stared uneasily past the burly gatekeepers, from whose mouths the breath streamed like jets of cigar smoke. Huge, dripping, rusty, pierced with broken windows, the complex looked like the set for a dead space colony in Dune, rotting and collapsing. There had been built within it, I soon discovered, whole villages of plaster and plywood whose purpose people had lost track of.

It was among these cathedrals of terminal decay on the outskirts of Moscow that Bondarchiuk was attempting to proceed with the last grand project of Soviet cinema. His idea was to adapt Sholokhov's four-volume novel of Cossack life during the revolutionary upheaval into a 10-part television serial and, cut from that, an international feature film; and to this end the enterprise had joined forces with Dino De Laurentiis, the Italian producer. I was urged forward into the forbidding labyrinth. It was suffused with the mingled odors of gas, oil, urine, and gravy. I traversed long corridors once decorated in the grim non-color schemes perfected by totalitarianism, now peeling, cracked, and mildewed, but still heated by vast archaic systems, which shuddered and hissed. The soundstages were infinities of vastness and utter darkness, for only essential lighting was, at that time, possible. One might have expected Chaliapin or Diaghilev to boom at one from the impenetrable depths, but actually it was Rupert Everett who trotted towards me. I gave a little wave. We smiled in wry disbelief.

"Good God, you're here," he'd said, calling my hotel a day earlier to check. "I'm amazed -- because it was a forgery."

"What was?"

"Your official letter of invitation."

"A forgery? Forged by whom?"

"By me."

"By you."

"There was nobody here who could send one, so I sent one, in Russian, full of spelling mistakes."

"Oh -- will we be sent to prison?"

"I don't think so. Everyone's been on strike. I don't know if I'm working tomorrow. The Italians were on strike because they'd not been paid, the studio was on strike because they'd not been paid. It's chaos."

An Italian-Russian production in chaos? What a surprise. Plus the little matter of imperial Soviet collapse. Only this could answer the weird question of why Rupert Everett was in the film at all, as well as playing the male lead, the young Cossack soldier who elopes with another man's wife. In the final whimper of the USSR, it seemed that anything went. As an actor he was also doing his best to rise to the epic occasion. During the day, for example, Rupert wore a false mustache. On reflection it is odd that he didn't simply grow one. But yes, he was "working tomorrow"; and the car had come for me.

Rupert didn't have a dressing room, but he did have a bed in a nook adjacent to the set. "Do sit on my bed," he said. He's very tall and was dressed in a Cossack outfit. "It's a tragedy -- all the Cossacks get wiped out. Bondarchiuk is very famous here. He's the Russian David Lean. This is Tania."

"How do you do," she said. "But I should say that Bondarchiuk is not a Russian but a Soviet director. There's a difference, you understand?"

She was the liaison officer, with that ethereal and pearly Russian look, and she gave me some English-language press releases, in which the great director's surname was indeed spelled with an i. "That's Bondarchiuk over there," whispered Rupert, rather as the naturalist David Attenborough might indicate an orangutan in the shadowy Borneo forest.

I looked across. In a distant corner of the set, pinioned by a rare shaft of lamplight, stood an old man with thick white hair, conservatively dressed in a brown jacket and dark trousers. Bondarchiuk's only striking feature was that he wore black-framed spectacles exactly like those of Michael Caine in The Ipcress File.

"Come and meet him," suggested Tania, who added, "He is old-fashioned, and many people are now against his work. How do you find Moscow?"

"I find the Russians fantastically attractive. I don't know why. It's a crazy place, but it touches me," I added.

"I understand the crazy part," she replied, giggling. Clambering through the murk, over poles and boards and indecipherable blocks of stuff in random disarray, she led me into the presence. The director gave me a brief, genuine smile, then switched it off as though somebody had pinched his bottom. Rupert told me Sergei didn't waste gestures. Even his minimalism was epic. Some minutes later shooting began, and the maestro uttered a curt, "Action," which I believe was the limit of his English.

A maiden of the steppes in her simulated log cabin declaimed, "I wasn't expecting you. It's a long time since you were here." Rupert, a greatcoat thrown over one shoulder, mumbled something surly and inaudible in response. Then they all stopped. It was the first of many, many takes. This was the old Soviet spaciousness in which a production would be given a starting date but no completion date. At lunchtime, the Russians went off to their cabbagey canteen. The Italians had their own cook and eating place, and I joined them in a passable mock-up of a trattoria in Bologna. Rupert disappeared. A bowl of spaghetti later, someone asked me, "Have you seen Rupert? Everyone's looking for him." His assistant, Bruno, trundled across with palms upturned and said, "They've lost Rupert." So I had some more spaghetti. There's something about hanging around for hours in those old concentration-camp studios that leaves you starving. "What do you miss most in Moscow, Bruno?" I asked. "Small talk," he replied.

Tania later showed up to announce, "Rupert has been localized!" There was a satisfied relish in her voice, which made it sound like some KGB specialty. He'd been doing pictures with our photographer. Later on I interviewed him about his life in Russia -- yes, he said, the filming was so slow he'd had to move there. He loved going to clubs, but there were no gay clubs in Moscow -- no bar or cafe life of any sort -- so he simply shared a flat with Bruno. (A full account of this interview appears in my book 20th Century Characters).

But And Quiet Flows the Don sank without trace.

Courtesy of Desiree Corridoni-Hair Designer HOD

Soon after working with Everett, Sergei Bondarchiuk had a violent altercation with the Italian co-producers and the miles of Don tapes were locked in a bank vault, after which, in 1994, Bondarchiuk promptly died from frustration in the form of a heart attack. Did he take the vault key with him? Were the tapes still in the vault? How could they be salvaged? It was President Putin who eventually asked these questions and took up the cause (Putin has an unusual interest in cinema and personally effected, for example, the financing of Alexander Sokurov's avant-garde film Faust). In consequence, the Don tapes were extricated from their impasse and edited by Bondarchiuk's son, Fyodor, and shown eventually as a reduced seven-part television serial in Russia, to horrible reviews. Rupert, in particular, got it in the neck for being, let us say, lukewarm in his performance. A feature-film version, also cut by Fyodor Bondarchiuk and a paltry three hours long, was released on DVD in 2011. It is a "selection" of scenes from the television series. The drama is elusive, the acting and dubbing worse than in Oklahoma, and even Rupert, whose gift for deadpan ridicule has become his second career, is lost for words in recollecting it -- but the Bondarchiuk touch is notable in the work's dizzying panoramas.

As for the director's Waterloo, which I'd purchased secondhand in London, I discovered that this is cinema of a different caliber. In fact it is Bondarchiuk's masterpiece, with a dreamlike control of silence and noise, psychological intimacy and Cyclopean spectacle, and -- surprisingly -- a fine, lean script. The battle itself is filmed to authentic scale and gaspingly choreographed: Bondarchiuk was able to deploy the cavalry and infantry skills of the Soviet Army in empty Ukrainian landscapes against vast blue or flame-painted skies. Christopher Plummer and Rod Steiger are riveting as Wellington and Napoleon respectively, as is Orson Welles (whom I once met in the King's Road, Chelsea -- but that's another story) doing a dropsical Louis XVIII. The Reggia di Caserta, a gargantuan wonder near Naples, stands in for the Tuileries Palace, and also for Fontainebleau Palace, and outplays them both. Try to find a DVD of it, because even viewed on the small screen Waterloo is an overwhelming experience and its like will never be made again.