Before Alex Anwandter brought his first feature film to the Seattle Film Festival in June, the Chilean musician wondered if a U.S. audience would connect with a movie about the murder of a gay teen. After all, the openly gay writer-director thought homophobic violence wasn't as prevalent in certain areas of the U.S. as it once was.

Then, just days after Nunca Vas A Estar Solo (You'll Never Be Alone) was shown in Seattle, Omar Mateen killed 49 people and wounded 53 others at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

"It was an open wound," Anwandter said. "You'd think with the [awareness] existing, we would have advanced in protecting our fellow citizens, but it's just not the case. It's incredible."

Nunca Vas A Estar Solo (You'll Never Be Alone) was inspired by the 2012 murder of gay teen Daniel Zamudio, but Anwandter emphasizes that the film is not just about the Zamudio case. Instead, it is the fictional story depicting how the murder of gay teen Pablo (Andrew Bargsted) affects his father, Juan (Sergio Hernandez).

The film, which won the Teddy Award during the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, had its theatrical debut Nov. 10 in Santiago.

During a recent interview over Skype, the 33-year-old artist spoke about his film, his latest Latin Grammy-nominated album, Amiga, and the activist spirit of his art.

Out: Your film makes me think of the Matthew Shepherd case in Wyoming back in the 1990s.

Alex Anwandter: The boy who was murdered was, for Chile, our Matthew Shepherd. One of the things that most disturbed me when the murder happened, beyond the specific violence, was the lack of quality in the debate that came afterwards. The murder inspired homophobic discourse in mainstream media and eventually in fictions. Namely, newscasts reported that the boy had been murdered "because he was homosexual," as opposed to because he was attacked by a homophobic gang. It kind of guided me toward the necessity of transcending this one boy and exploring the context and the values shared by the society that shelters this type of violence.

Why did you focus a lot on the fictional victim's father?

It's a way of me saying it's not one boy that got murdered, one time, four years ago. It's something that happens every day in many places, not just a specific neighborhood and street corner, or a country, city, continent.

One of the main narrative devices to shift the focus of the analysis toward this context was to focus on this symbolic figure of the father, who is the person in charge in most societies. What is it to be a man? Or what isn't a man supposed to be? As a symbol, I thought a father figure would be a powerful way to transmit that.

Did Daniel Zamudio's real-life case change anything in Chile? Was there new legislation or new legal protections for gays?

We got our first ever anti-discrimination law passed after his murder, but I really have to emphasize that not much has changed otherwise. Still, other kids were attacked and even murdered, and those cases are not famous. It's very hard to measure the progress when violence still exists.

When something like this inspires you to write, what made you decide to go with a film as opposed to a song?

No one really identifies themselves as the perpetrator of violence or with the perpetrators. No one really says of themselves, "I am extremely homophobic. I discriminate so much." That thought just doesn't exist. I thought a screenplay for a fiction movie would be more like a deeper vehicle for this type of reflection. And I can't write a novel or anything, so I wrote a movie.

How did the experience of making your first feature differ from making music?

It was extremely different. I had directed several music videos and I thought that would have been helpful. [Laughs.] But it wasn't because it's such a huge endeavor, really, to make a feature film. What I did get from my previous music video experience was gaining an awareness of how important it is to create powerful images that stay with the audience even after they leave the theater. It needs to be sensory and visceral and emotional. That's why I purposefully made such an emotional movie, because I don't think people will identify themselves with the oppressors. They have to identify themselves with the people who suffer this type of violence. Emotion and images are an extremely powerful way to achieve that.

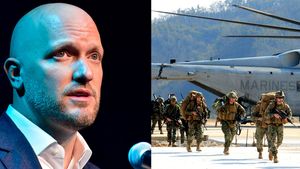

Writer-director Alex Anwandter. Photo by Rod at Rod Photography.

Is your hope to teach possible oppressors a little bit of love, understanding? A little bit of caring, tolerance?

I try not to think about it in that way, because I think it's not the smartest strategy. I think my empathy is very clear, that it's with the victims of violence. But at the same time, I think it's very important to not point fingers. I think it's a healthier community exercise to think together, as opposed to having yet another person telling people what they should be thinking.

Are you bringing your honesty and your beliefs to your art?

Absolutely. I think people appreciate art that transcends. We have an expression here, "Looking at your belly button." It means preoccupying yourself with only your intimacy and not seeing that even in intimate fears, politics are at stake. I'm very aware that here in Chile, me holding hands with a man in the street is a very intimate activity or gesture, and at the same time it's permeated by a political climate that hasn't allowed that to happen here. In the U.S. it's been allowed legally, but a cultural climate there still sometimes punishes it in certain areas. I think audiences really appreciate--and I appreciate as an exercise, as a person, as an artist--trying to connect those spheres.

Film aside, you recently received a Grammy nomination for your album Amiga. What's the story behind the title?

The whole album is a musical poem and reflection on what it is to be a man, as opposed to a woman. There are a lot of ideas regarding that and regarding femininity and how that connects with biographical or more personal stories of mine. There's a lot of commenting on how you perceive and define yourself. Amiga is like saying "girlfriend," but when two men could say, "Hey, girlfriend," to each other. It's also used like that here. It's a word very open to interpretation, just like the album.

What inspires your style of music?

That's a very good and difficult question. I think what I strive for the most is connection. A connection with myself and my context and with my context's struggles. I really tried to make a wholeness in those areas of me and my life. I think it's very important and I think part of my style or aesthetic stems from that--to visualize who you are and the ways that you are different and unique. Not because of some megalomaniac instinct, but because I think it's very healthy for all of us to accept one another and appreciate the richness of diversity. A very powerful way of doing that is being authentic and forthcoming and honest with the audience and yourself.

What artists influenced you?

I really like pop music and dance music, especially dance music that's been connected historically to gay communities or queer communities. I really like female singers, like Grace Jones or Nina Simone. Maybe even more than musicians, I'm attracted to these powerful, icon-type of figures. I also like David Bowie and Prince, who did not conform to norms. Their art is as much about musicianship as identity.

You've been outspoken and political on your albums. Is that the norm for Chilean artists?

Oh no, not at all. Chile, as much as any other country, has tons and tons of issues and all sorts of people that are being oppressed by either culture or the state or whatever other groups of people. For me as an artist, it's a strange exercise not to include that in your art. When I get asked, "How come you're doing this?" My reaction is thinking, How come other people are not doing this?

Do you consider yourself a spokesperson for LGBT issues?

No, because I don't think I know enough from other people's lives to anoint myself as a spokesperson. What I do consider myself is an activist of some sort, but in the sense that any citizen can be an activist, use their own work as a platform for making wherever you live a more accepting place.

Watch an exclusive clip from Nunca Vas A Estar Solo (You'll Never Be Alone) below:

Nunca Vas A Estar Solo (You'll Never Be Alone) is now playing in Santiago and will be screened this weekend at the Latin American Film and Art Festival in Los Angeles. Find more information here.