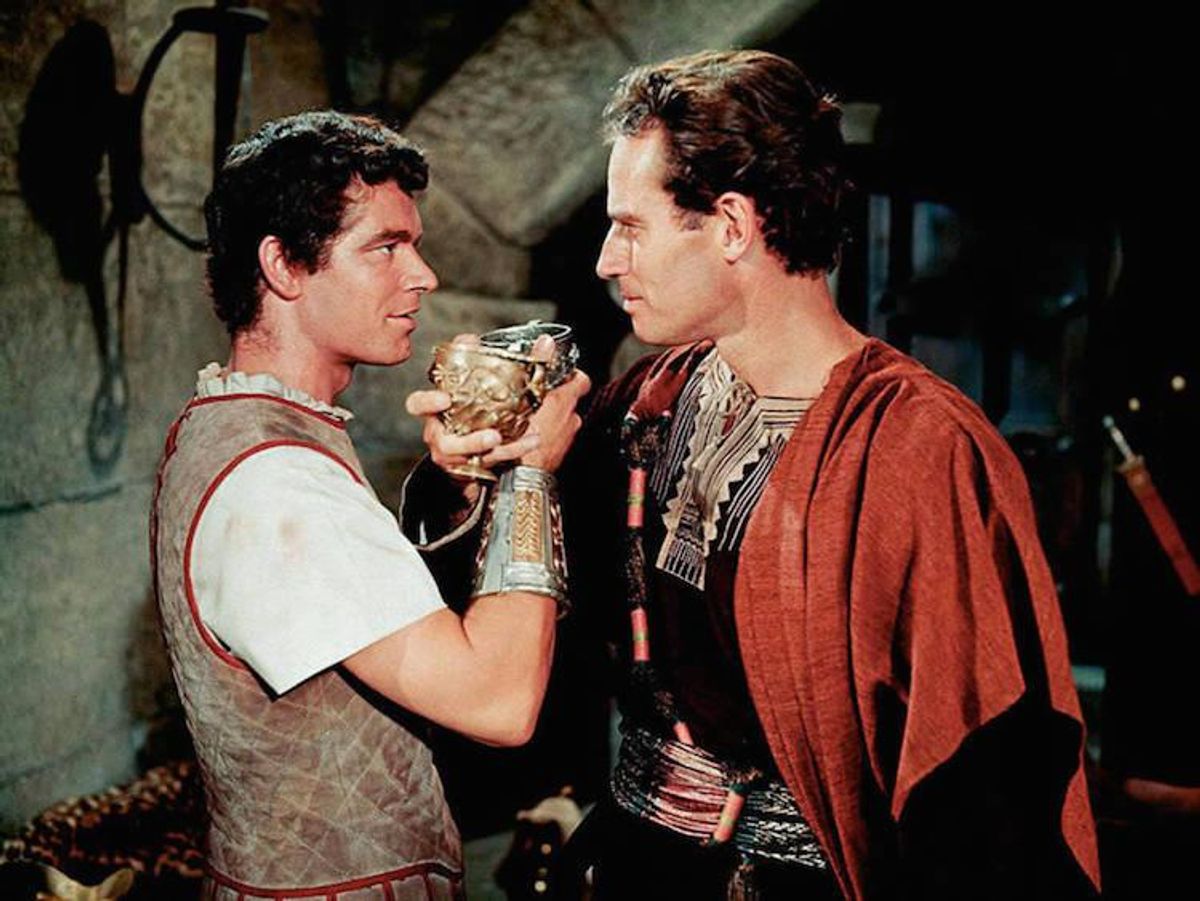

Stephen Boyd (L) & Charlton Heston (R) in Ben-Hur (1959)

We don't really do subtexts in the see-through, digital 21st century. Sexts, definitely. Subtweets, possibly. Subtexts, not so much. Who has the time? Who can even be bothered with having a subconscious? Subtexts are so analogue.

Toby Kebbell, who plays Messala in the 2016 remake of Ben-Hur with Jack Heston as Hur, announced recently that there is "no gay subplot" in the new version, explaining that it's "not necessary today."

But back in 1959, when William Wyler's Technicolor version of the chariot-racing, Jesus-praising epic was unleashed (scooping up a record 11 Oscars) repression and subtexts were all the rage. They made High Hollywood what it was. And Ben-Hur, a story about two boyhood buddies who dramatically fall out as adults, has one of the most famous--and bitterly contested--gay subtexts in Hollywood history.

As Gore Vidal, an MGM screenwriter in the 1950s, put it in the 1991 documentary The Celluloid Closet, navigating the mores of the time meant "you got very good at projecting subtexts without saying a word about what you were doing. The best example I lived through was writing Ben-Hur."

Vidal claimed that he had convinced an initially reluctant Wyler that the only way to justify several hours of widescreen, living Technicolor hatred between Jewish prince Judah Ben Hur, played by Charlton Heston, and the Roman Messala, played by Stephen Boyd, was to have an unspoken homoerotic backstory--and that this was, in effect, an epic lover's tiff.

Vidal's plan was to suggest in the beginning scene of the movie, when the boyhood best buddies are reunited, that they were once lovers, and that Messala very much wants to pick up where they had left off, but is jilted by Hur.

According to Vidal, Boyd was told the subplot idea, and loved it, but Heston was spared the knowledge, Wyler advising: "Don't say anything to Chuck because he will fall apart."

A prescient warning.

Heston, close friend of Ronald Reagan and former president of the National Rifle Association, reacted furiously to Vidal's interview and denied everything, essentially calling him a liar and a braggart in a letter to the papers: "Vidal's claim that he slipped in a scene implying a homosexual relationship between the two men insults Willy Wyler and, I have to say, irritates the hell out of me."

Naughty Gore! 'Slipping' homosexuality into Heston's biggest, butchest picture!

Vidal of course responded. This time, no Vaseline. Even more "irritatingly," he quoted from a letter the publicity director for the film had sent him: "The big cornpone [the crew's nickname for Heston] really threw himself into your 'first meeting' scene yesterday. You should have seen these boys embrace!"

Certainly, when you watch that scene now, Vidal's account makes perfect sense. Boyd has a look of total love on greeting Heston, his eyes roving hungrily all over his beloved's face and, almost imperceptibly, his body. While Heston looks slightly nonplussed.

Quipping in reply to Hur's suggestion that the Emperor's interest in Judea is not appreciated by Judea, Messala even speaks the line: "Is there anything so sad as unrequited love?"

Wyler however claimed not to remember the conversation Vidal reported, and that the scene he wrote was rewritten by another screenwriter (though there is evidence that a significant amount of Vidal's input survived into the final version of the movie script).

But whether or not Vidal was having some mischievous fun slipping in a homoerotic subtext at the time or decades later, trying to detect it is now the most interesting aspect of the often tedious, pompous movie.

A year after Ben-Hur, Stanley Kubrick's sword and sandal epic Spartacus (1960) was released, minus a bath scene in which the Roman general Crassus, played by a middle-aged Lawrence Olivier, attempts to seduce his "bodyservant" slave Antoninus, played by Tony Curtis in his doe-eyed prime, through a heavily suggestive dialogue about "eating snails" and "eating oysters."

Preview audiences expressed their moral distaste and the scene was cut (but restored in the 1991 rerelease). Lord knows what they would have made of the recent TV series of the same name that featured some very explicit snail-eating.

Sword and sandal movies had a snail-eating reputation anyway: all that muscle, leather, slavery, and pagan license. The 1950s underground gay mag Physique Pictorial often used Greco-Roman imagery.

Although male homoerotic subtext had served Hollywood well from the '50s to the '70s in classic movies such as Rebel Without a Cause (1955), Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid (1969), and Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974)--giving them both universal appeal and psychological depth--by the 1980s the increasing visibility of gay people and the growing influence of gay culture on the mainstream meant that homoerotic subtext was having more and more difficulty staying sub.

Tony Scott's flyboy blockbuster Top Gun, released in 1986--about halfway between now and 1959's Ben-Hur--starring Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer as rival Navy pilots slathered in hair gel and smugness--saw the gay subtext, intended or not, swallow the script.

The official, patriotic, heterosexual storyline is completely eclipsed by the steamy sexual tension between rivals Kilmer and Cruise, frequently acted out in changing room scenes that look like a Roman bath-house. Or maybe a Matt Sterling one.

Top Gun is an airborne, way gayer Ben-Hur, but with a happier ending.

Although most of the people who went to see Top Gun in 1986 probably didn't notice, by the beginning of the 21st Century we had all become far too knowing for gay subtexts to stay sub. In its place, Hollywood was offering us out gay storylines, and self-conscious, chaste "bromances," in which, almost by definition, anything physical would be a kind of incest.

This history of gay subtext makes me worry how the Ben-Hur remake can dare to erase its queer undertones. But perhaps to ward off any attempt for a gay reading, the reboot has made Hur and Messala "adoptive brothers," instead of boyhood pals. A literal, legal, "bromance"--albeit one that goes very wrong indeed.

The Ben-Hur remake hits theaters on August 19. Watch the trailer below:

Read more of Mark Simpson's writing at MarkSimpson.com.