Movies

How D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms Originated the Gay Film Hero

How D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms Originated the Gay Film Hero

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

How D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms Originated the Gay Film Hero

Most queer film historians cite the 1919 German movie Different From the Others (Anders als die Andern) as the first gay cinematic landmark, but released that same year was an American movie, Broken Blossoms, by the legendary D.W. Griffith, that captured a gay essence. It was in sync with the understated discretion of the times but, today, reveals a wealth of telling and affecting emotional detail.

It starts with an outsider, Cheng Huan (played unforgettably by Richard Barthelmess), a Buddhist who leaves China and travels to the West "to take the glorious message of peace to the barbarous Anglo-Saxons, sons of turmoil and strife." Sensitive Huan, in his flowing robes, is contrasted with a gang of "jackies" -- roughhousing sailors who resemble Tom of Finland and Bruce Weber hunks. In London's impoverished Limehouse district, he encounters crude machismo in the alcoholic boxer Battling Burrows (Donald Crisp) and then beholds fragile, enchanting beauty in Burrows's teenage daughter Lucy (Lillian Gish). These virtuous-brutish-virginal types might seem corny, but they're actually poetic ideals. Griffith's silent films used sentimental archetypes found in Shakespeare plays and Charles Dickens novels. That's what enables our modern sophistication to recognize the codes that make Cheng Huan a gay paradigm.

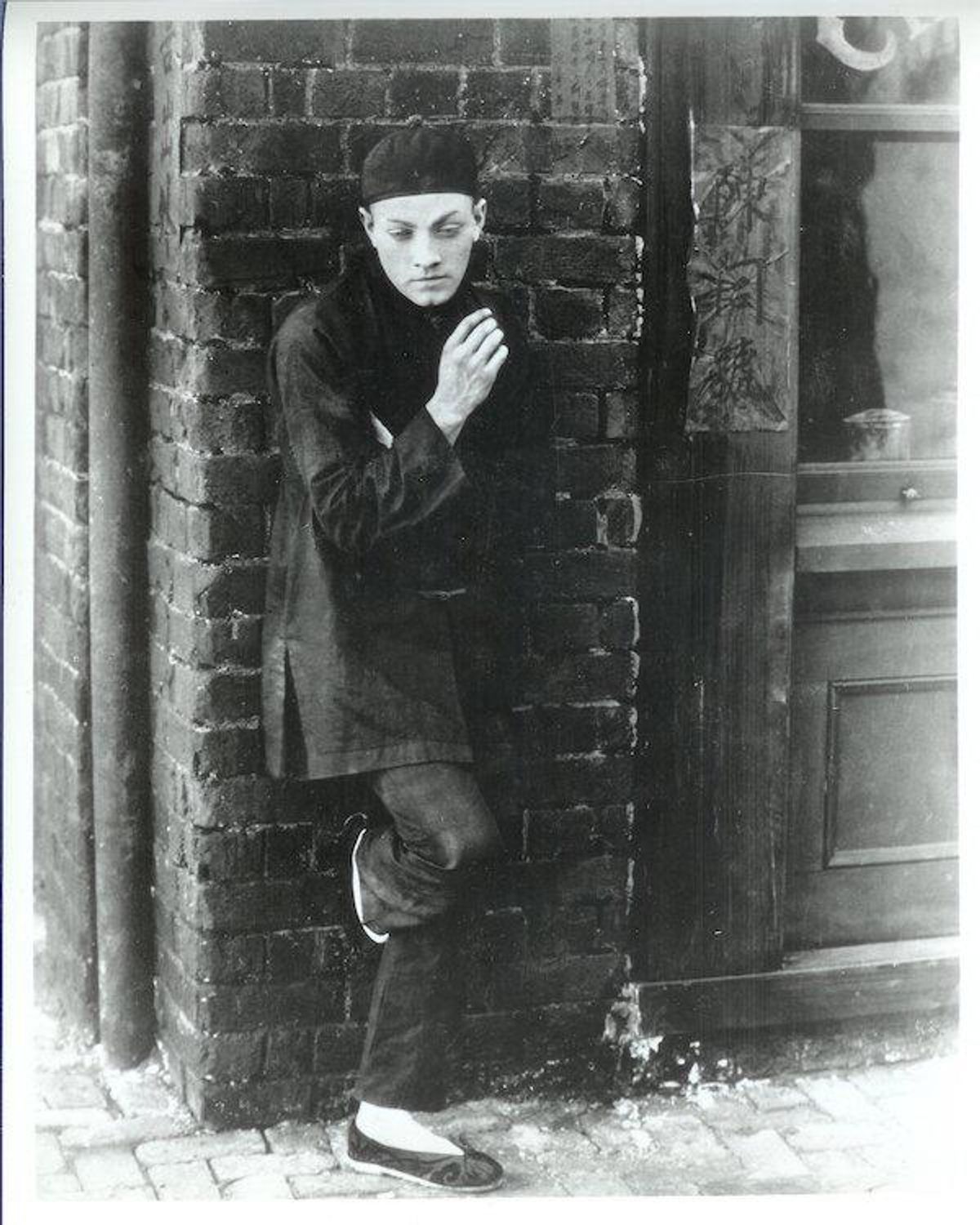

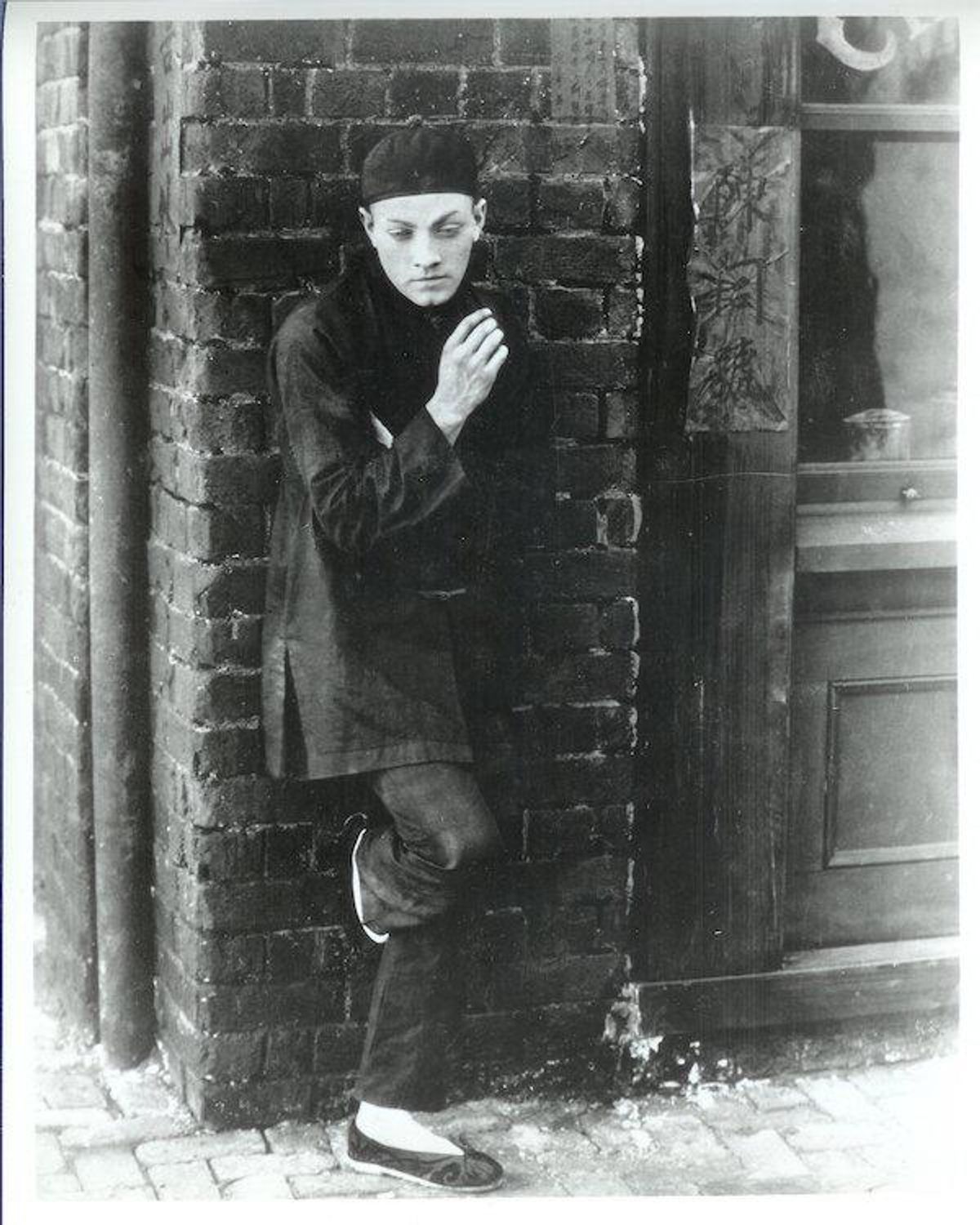

Barthelmess's Huan is both a pacifist response to World War I and the first on-screen instance of the Sad Young Man, that solitary figure whose misunderstood gentility and loneliness hid his elegant taste and discreet eroticism. Barthelmess exquisitely mimes Huan's delicate personality. The iconic image of him huddled on a London street corner with his languid, slanted eyes, and his long and shapely fingernails and left knee crooked to steady himself (almost a concubine's stance), is the farthest thing from a racist caricature. Who can doubt that Griffith knew exactly what he was doing while pushing male portrayal this far toward femininity?

Griffith's empathetic vision is reflected by the purity of Huan's infatuation with Lucy. This is an interracial love story not in the sexual sense but in terms of gender identification. Huan rescues Lucy from her hellish home life and builds a shrine to her. Intertitles tell us "The beauty which all Limehouse missed smote him to the heart. The child with tear-aged face." It is cinema's first instance of pansexual empathy. No matter the controversy of Griffith's The Birth of a Nation, the filmmaker knew more about the practice of racism than today's smug hindsight will admit. Huan adores Lucy (nicknaming her "White Blossom") as much as European colonialism insists on Third World servitude.

But an enlightening change comes with the intensity of a male's identification with a female -- and Griffith's unmistakable objection to bigotry and cruelty. More intertitles carry a timely lesson: "We may believe there are no Battling Burrows, striking the helpless with brutal whip -- but do we not ourselves use the whip of unkind words and deeds?" In this movie, Griffith and Barthelmess originated the Hollywood industry's sympathy for vulnerable young men that eventually enshrined Dickie Moore, Brandon DeWilde, Sal Mineo, Anthony Perkins, and Elijah Wood.

Film buffs esteem Broken Blossoms for its artiness -- dreamlike, fuzzy images project us into the exoticism of other states of being. It heightens our response to effeminacy while critiquing Battling Burrows's masculine threat. Crisp's macho sneer is on a behavioral continuum with Gish's fragility (her fright hiding in a closet was repeated in Brian DePalma's modern sexual gothic Carrie) and Barthelmess's ethereal, idealized compassion. The man and girl's idyll is crushed ("The spirit of beauty breaks her blossoms all about his chamber"), and no contemporary gay-bashing would be more heartrending. "His love remains a pure and holy thing," Griffith's titles read, but we also know this mutual sensitivity is what used to be called "the love that dare not speak its name." With its exquisite message, why hasn't Broken Blossoms been remade?

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.