Rainer Werner Fassbinder,the most prolific major gay director of the past half-century--44 films from 1965 to 1982--made only three with gay protagonists. The most accessible of them is Fox and His Friends (1975), in which Fassbinder played the leading role. As the carnival performer Fox (the nickname, a diminutive for Franz, is appliqued in studs on the back of his denim jacket), Fassbinder portrayed an unsophisticated working-class man with a cute bum and zero sophistication.

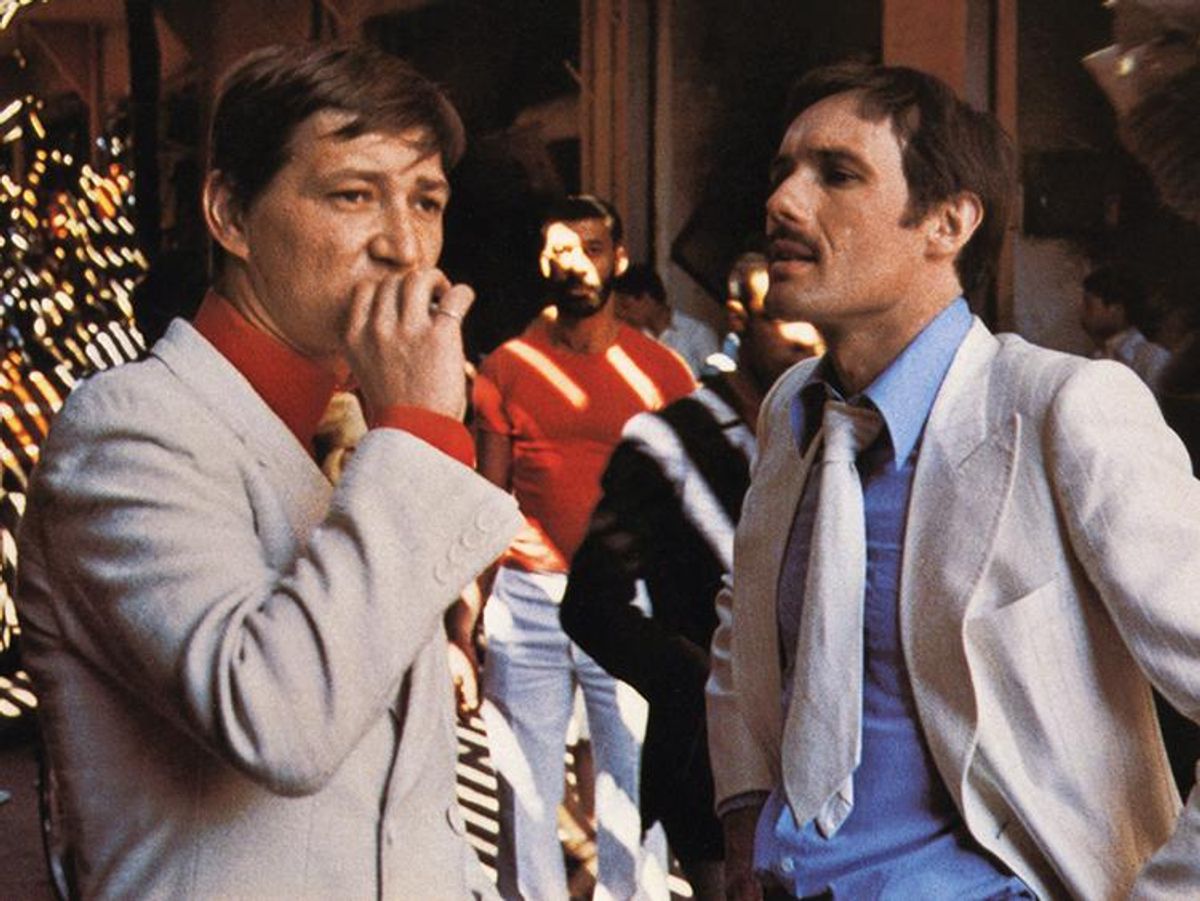

In this sexy, tragic narrative, Fox wins the German lottery but then loses everything in an exploitative relationship with a social-climbing lover, Eugen (a mustachioed Peter Chatel), who swindles him to protect his bourgeois family of publishing-industry titans.

On Criterion's newly released Blu-ray edition of Fox and His Friends, one of Fassbinder's regular cast members, Harry Baer (who plays Fox's classically handsome rival), recalls that the filmmaker was interested in "holding a mirror to society." It's a succinct explanation of what set Fassbinder apart from most gay filmmakers, and it's why he remains important and radical today.

Fassbinder's mirror reflected a deep, warts-and-all image of queer identity, unlike the flattering portrayals of social acceptance and middle-class advantage associated with many of today's movies and TV shows. That's because as early as his first full-length feature, Love Is Colder Than Death (1969), Fassbinder honestly expressed the tenor of the gay experience. He had the courage to dramatize gays alongside the rest of humanity without separating queer sensibility (conveying same-sex desire even among heterosexual characters) from his understanding of the larger world. His filmmaking was in the minority, but he never showed gays as a minority.

Fox and His Friends contains Fassbinder's most pointed social observation. It is a movie in which he critiques class--the economic, ethnic, and cultural differences that divide even gay people from each other. This should leave contemporary queer viewers skeptical about mainstream media's tendency to talk down to us with idealized all-smiling, all-successful depictions.

The original title of Fox and His Friends is Faustrecht der Freiheit, which translates as "Might Makes Right." It questions the conventional social authority that often oppresses those who, like gay, naive Fox, go through life unaware that they lack social power. In Fassbinder's selfless mirror, the tension between affluent, cultured gays and poor, uncouth gays reflects an inhumanity that queers ought to be able to recognize and resist.

Few contemporary filmmakers follow Fassbinder's bold example. Even Todd Haynes's secondhand Fassbinder imitations in Carol (copying The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant) and Far From Heaven (copying Fear Eats the Soul) lack equivalent political analysis. There are unforgettable moments that show Fox in conflict with his society's unquestioned standards, such as when he meets an art dealer in a lavatory hookup, or when Fox and Eugen are in Morocco and bargain over "package size" with an Arab hustler (played by stunningly virile El Hedi ben Salem, Fassbinder's real-life lover).

Before and after Stonewall, Hollywood often over-sensitized its closeted gay characters, portraying them primarily as victims. But Fassbinder's greatness can be measured by his resistance to self-pity. Fox's tragedy stems from his unschooled belief in a political and economic system that confuses cultural status and social acceptance with personal fulfillment.

Fassbinder's mirror revealed other tough truths, including gay men's insensitivity to each other. A scene in which Fox and a trick enjoy a mud bath at a spa while checking out the passing meat parade provides a new twist to the old saying "lie down with dogs, wake up with fleas." Fassbinder could portray Fox with such charm and pathos because he was acknowledging his own humanity and reprimanding his own flaws. His final film, Querelle, a masterpiece, would go even deeper, but in Fox and His Friends, Fassbinder's outsider art stands above the usual tropes of queer cinema and above fashionable platitudes.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.