We're living in an era when the most basic of human rights like free speech seem to be at play. But nothing compares to those who came before us, the many who died at the blind eye of a government and a society that chose to see them as deviants.

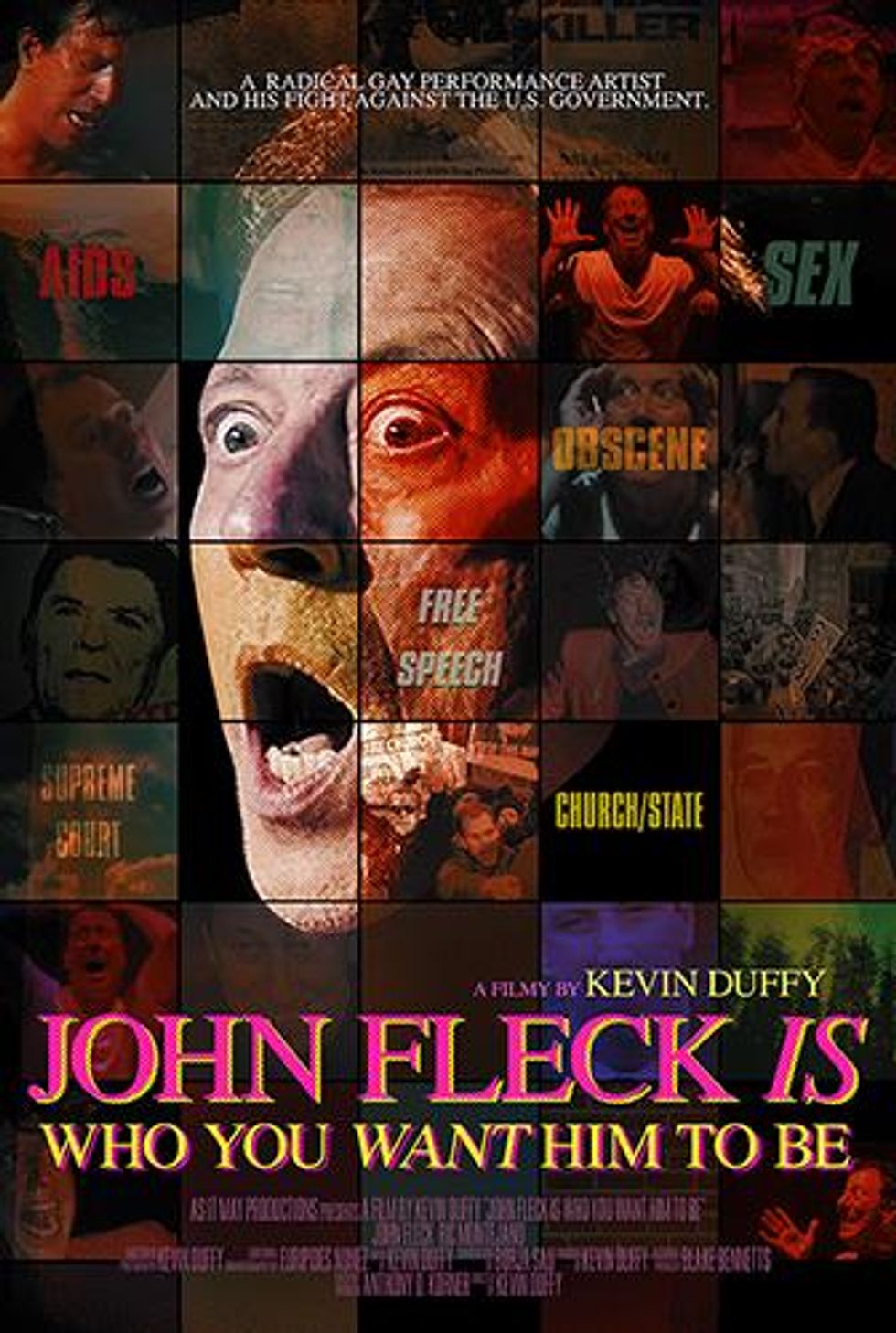

Although the AIDS epidemic has been depicted through many narratives in films, TV shows, and literature of recent years, Kevin Duffy offers an all but forgotten story. In John Fleck Is Who You Want Him to Be, Duffy draws attention to four artists who took on sexuality and AIDS in 1990, only to have their funding pulled by the National Endowment for the Arts. Years later, Duffy caught up with Fleck, a member of the "NEA 4" to shed light on a career and a work of art that was deemed too controversial.

We recently spoke with Duffy as he prepares to screen the documentary at the New York Indie Theatre Film Festival. Discussing the use of body and performance art as protest, he explains why the work of John Fleck is so relevant today.

When did you first discover John Fleck?

I was a performer, doing theater in New York in the '80s. So, I was very aware of who John was. He would come and perform in New York occasionally, and he had a reputation. In 1990, when the government reversed funding to four artists, three of whom were queer, at the height of the AIDS crisis, that of course put them all on the front pages at the time.

How did you actually meet?

We live in the same neighborhood. We both live in Los Feliz. At one point, he started talking about his archives. He was concerned about them. That was the legacy of his work, all the work he had done. So, he wanted me to look at it with him, sort of go through it, organize it, all of that. And I just got the idea when I saw it. I said, "John, we have to do something with that." That was the way the project came about, through the archives. And then I just started following him when he had a project, he had a show going on. And that is how the film came to be.

So many narratives from the AIDS crisis have made their ways into pop culture and documentaries like this. Why was this one so important to you?

Well, there's a problem that resulted because of this. I just saw Paris is Burning again, and that's a great film. That was made in 1990, and that received funding from the NEA. So back then, that was an important part of our culture, doing exactly what we needed to be doing as a culture, even when it was difficult or different. But the artists who were defunded--John Fleck, Karen Finley, Holly Hughes, and Tim Miller--again, they're all incredible artists, three of them queer. Their work all addressed issues of sexuality and the AIDS crisis in some way. Then they were shut down. There was a legal battle about the funding, which was sort of resolved in their favor. But as a result, under the Clinton administration, there was a clause called "the decency clause" that went through Congress and was upheld by the Supreme Court, but in sort of a controversial movement. And it says that funding must respect the diverse beliefs of the American people. So, when you see John's work and you see the piece that was effectively banned at the time, you can see that he was attacking the religious right because they were attacking us. So, he was trying to strike back at them, and that's what got him in trouble with the government. But no one has seen that piece since then. This decency clause made it through the entire political system. You know, as a citizen filmmaker, we can't ignore the First Amendment issues there. There's no law regarding the establishment of religion. It's something that happened in the AIDS crisis and it wasn't resolved until later in the '90s. This was just something that was left aside.

With John Fleck at your disposal, what was the research process like?

It was difficult. Dealing with the archival footage was very challenging, because I knew I had to show the piece. I knew that piece was going to be difficult, and I knew it was essential to the story. So, I had to create a film leading up to that moment, when he did that performance. It was difficult for me. I was raised Catholic. I went through the AIDS crisis in New York. The church was attacking us. There were things like that going on through the country at the time. So, it brought up a lot of memories. It was a very difficult time, and kind of difficult to go back there, through the lens of his work. At the same time, John is incredibly funny and incredibly warm. So, the film is mostly watching him, and he's delightful. It had to go to this dark place, because that is what happened, that is what we were all going through at the time.

What was the most interesting thing you learned about him during this process?

I don't want to give away the film, but the film is structured in three narrative arcs. There's the archival footage, and the most intense part of that is the piece that was banned. There's me following him in the course of his performances in LA and New York. Then, there's an interview with him, where we sit down and have a conversation. And I actually got him to reveal some things in that conversation that are things I think he doesn't say all the time. In fact, he whispered some of it, and we had to go back and work on the audio a lot. So, I think he managed to reveal himself in a way that was very surprising and very moving.

Seeing him perform so many years later, how would you say he's evolved as an artist?

I know him so well as a performer, and he has an incredible depth and an incredible expression of looks. His face and his voice and the way he sings. There's an expressiveness and a depth to his work that I think have only gotten stronger.

How would you explain the importance of using performance art, or just art in general, as a form of protest?

In the AIDS crisis, which is when this whole story started, it was literally a crisis of the body. It was a health crisis. And there were artists who were using their bodies, putting their bodies on the line, onstage to express their rage, to try to provoke a response from the government and from the media. It was a very different time because there was a lot less media, and it was much more controlled that way. So, I think it's kind of the ultimate artistic act, and it can be the ultimate political statement, because you're actually placing your body in view, in front of other people, making yourself vulnerable, putting yourself at that kind of risk. And I think that continues, we see that today in various kinds of protests. And it's also interesting because there's the cliche of "art for art's sake" but it was fun and it was entertaining, but it wasn't just about the art. There were bigger issues.

In promoting the film, would you say you've seen a parallel with today's administration coming after free speech and freedom of the press and LGBTQ rights?

Absolutely, I think this history shows us how important free speech is, how important art can be, and how important protest is. So yes, I find it completely relevant.

How would you explain the audience reactions, from activists of different generations?

For the people who were there, I think it can be very intense to go back to the traumatic times. There's a man in the film, a friend of John Fleck, Ric Montejano, a person with AIDS. They worked together, and they were great friends. You just see them going through their process of when they were staging their performances, and I think that's really inspiring to people. Unfortunately, Ric passed away right after we finished shooting. I think that's kind of a lesson for anyone to see this man so fully alive. With younger generations, it can be really interesting. We had a great showing at Cal State Long Beach, where they did a terrific job of explaining the context of performance art and the AIDS crisis and the culture wars of that time. If they're super young, there needs to be a bit of context, because it wasn't a politically correct time. It was much wilder, and the work reflects that. But if people can relax and enjoy it, they might find it funny and entertaining. They'll have a great time.

John Fleck Is Who You Want Him to Be will screen Saturday, February 3 at the New Ohio Theatre. Tickets are available online.