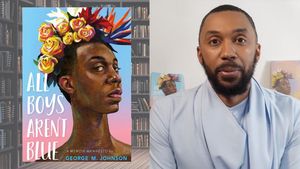

Photograph by Steven Meisel for 1984 'Like a Virgin' cover.

The image of Madonna courting a wild lion between ancient Roman pillars is one burned into the iconography of 1980s American music.

Alongside singer Cher's cannon-riding in "If I Could Turn Back Time" and Bonnie Tyler's lust for young pubescent boys in "Total Eclipse of the Heart," Madonna's gondola journey in Venice endures as an unparalleled transgressive pop culture moment.

Madonna released Like A Virgin, her second studio album, in November 1984, and today she releases Rebel Heart, her 13th. So it's worth taking a look at why her album of frank female sexual expression has remained a beacon for generations.

When her name, "Madonna," first emerged on the music charts in the early '80s, many had only heard the name in reference to the Christian Mother of God. The original "Madonna" was the matriarchal symbol of Roman Catholicism and Western Christianity. Madonna the entertainer, however, who moved languidly and beguilingly through the canals of Venice, soon proved she was unlike this original female figure of purity and divinity.

This Madonna burst onto the scene by violating all the innocent icons of religion and femininity that remained sacred symbols of Western religion. Madonna's conflation with being "like a virgin" began an uncharted trajectory into the realm of religion, politics, and, of course, sex in the world of pop music.

It was in 1984 that Madonna was pushing the envelope around the intersection of women and religion and actively mocking the cultural norms and ideologies around women and virginity. Using symbols such as the white wedding dress, rosary beads, and a cross covering her heart, Madonna articulated a backlash against these antiquated beliefs around women.

The album Like A Virgin soon defined Madonna as the seminal 1980s pop star, as she symbolically entered the culture war debates of the 1980s (sex, feminism, and career women) and helped change a generation of young girls into sexually expressive adults and alerted woman to the dated ideologies of religion and gender norms. Women idolized the transformative transgressions of Madonna, a star who wanted to be in control of sexual identity and dictate the terms of her own erotic encounters.

Like A Virgin spawned the iconic and eponymous song "Like A Virgin" that sat atop the charts worldwide for weeks. Fans of the songstress vigorously copied her aesthetic, the costume of torn cotton gloves, excessive necklaces and beads, and heavy mascara. The record also produced the song "Material Girl," which momentarily reframed Madonna as Marilyn Monroe's successor -- the blonde icon of a new generation -- but also pointed out her clever awareness of Hollywood's construction of the ultimate woman and blonde archetype.

While the album also led to the release of songs "Angel" (no doubt keeping the religious subtext of the album) and "Dress You Up" (gender performativity anyone?), Like A Virgin has since been defined by its hit single and its controversial music video.

Now some 30 later, rewatching the notorious video sees it pale in comparison with much of the explicitness of today's iconography of women, sex, and erotic excess. (Think: JLo's buxom "Booty" or Nicki Minaj's bulbous "Anaconda.") And yet there is a sound subtext of sexual awakening and self-conscious deflowering (only Madonna really gets off in the music video) that allows the song to retain its cultural potency today.

Like A Virginwas the album that put Madonna on the national map. The sight of the lithe and enticing figure cruising the canals of Italy directly engaged with her Italian heritage and placed a modern post-feminist woman in the setting. The presence of a roaring lion that soon evolved into a male figure (who is somewhat ridiculously wearing a bad lion mask) saw Madonna soon entertain a dalliance over the waters, dictating the terms of her erotic choices solely herself.

The ubiquity of that pulsating rhythmic repetition at the start of "Like A Virgin" has become symptomatic of unashamed autonomy for a woman to have over her body. Since "virginity" as a cultural construct and religious symbol had -- and continues to have -- an unparalleled hold over the sexual identity of women, Madonna's frank and ironic goading to the viewer mocks the power of the virginal girl. As virgins are to be unaware of the erotic power they had over their male lover, her wry smirking throughout suggests she knows otherwise.

Because Madonna in the video is ostensibly not a virgin, she subverts its power over her own sexuality. It would seem that she instead encourages male viewers -- voyeurs -- to believe that she retains a virginal nature, as lovemaking with Madonna would no doubt be characterised by its passionate erotic fulfilment and pleasure. At one point in the song she moans to her paramour, "Been saving it all for you/ ... You're so fine, and you're mine." The prized asset that a girl can preserve it would seem is her virginity -- and yet Madonna so wonderfully coaxes us all just as well in spite of her frankness about her own sexuality.

Of course, there are the parallel meanings between the Madonna (the Virgin Mary) and Our Like A Virgin Madonna. As the former story goes, the Holy Spirit impregnated the Virgin Mary with the Son of God, Jesus Christ. This "immaculate conception" has become a sacred story of the divinity of both god and Mary herself. Madonna has equally exploited the phrase, using it several years later for her greatest hits collection The Immaculate Collection (1990). In "Like A Virgin," Madonna intertextually entertains this connection through her name, her presence in Italy and its rich history tied to Roman Catholicism, and the potential erotic meaning that gondolas have traversing tight and narrow canals.

From a contextual perspective, another appeal of "Like A Virgin" was the way it reconstituted sex in mainstream music within discourses of religion and innocence. In a decade plagued by mass hysteria because of the HIV/AIDS crisis, and the way sex (for both heterosexual and homosexual couples) was characterized by illness, viral exchanges, and the threat of "contamination." Madonna's song moved away from discussing the seemingly abject nature of sex, in an epoch so preoccupied by the dangers of sex and illness. "Like A Virgin" told women that they could be in charge of their erotic agendas, could, should, and would enjoy their sexual escapades, and did not even have to be virgins to do so. (Maybe just act a little virginal?)

For the second single off the record "Material Girl," Madonna made a nod to a number of cultural icons, namely the cult of Marilyn Monroe. In the similarly memorable music video, Madonna re-enacts a scene from Monroe's film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) and coaxes her male lovers into giving her gifts of diamonds and jewellery. The song is a play on the careerist culture of 1980s post-feminism in which women sought to define themselves through their economic and material capital through their work and careers (and by whatever means possible). In traditional Madonna style, the song also demonstrated her fantastic ability to recreate another type of femininity -- that of the peroxide blonde of the 1950s -- and to reconstitute the image for 1980s music videos politics. This proved to be an early -- and incredibly successful -- performance that Madonna would carry with her for years to come. (Indeed she's still referred as the Material Girl in the tabloid press.)

Like A Virgin stands as a polemic for the reborn woman of the 1980s: empowered, sexually demonstrative, financially independent, and drawing on old antiquated traditions to move ahead in the world. Thirty years on, and with Madonna's new album including a host of collaborations, one can only guess how Madonna is bequeathing her notorious cultural commentaries to the new breed of women who are blossoming into pop stars.

Nathan Smith is a graduate student at the University of Melbourne Australia, specializing in queer and gender studies. His work has been published in Salon, The Advocate, and Out. He can be found tweeting @nathansmithr.