The storied legend of the Marlton Hotel, in the heart of New York's Greenwich Village, has been home to many: Jimi Hendrix, Marilyn Monroe and Valerie Solanis, the woman who infamously shot Andy Warhol. Adding his name to that list of the famous and the infamous is Natti Vogel, a Brooklyn-based piano singer/songwriter who grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In person, Vogel is an extraordinary presence with a larger-than-life personality: he speaks animatedly with his hands, his eyes widen with childlike wonder when he's excited (which is every five seconds), and he can't help but move his body sensuously, especially when he's talking about music and rhythm--you know, what really moves him.

We are here to talk about where he came from, and where he's going: currently, his debut EP, Serving Body is the focus. It is out July 26 and for an artist who's been gigging on the downtown New York cabaret scene since age 19, this is quite literally the most complete body of work he has served. The ornate, intricately arranged record is a study of early adulthood, including songs written from ages 22 to 25, replete with ironic social commentary and sexual politicking. Throughout the release, one can hear Natti's rigorous classical music training in its production, and a deep love of pop music in how sticky-sweet the tunes themselves feel.

I learn during our interview that he's also got a rebellious streak. Brought up in an academic family, he's a well-educated artist with an impressive academic and professional resume--from completing an advanced Mandarin Studies program from Harvard to apprenticing with renowned classical and Broadway composer Lance Horne. But the verbose, enthusiastic artist has never rested on privilege to carry him. The only thing muted about Natti was his choice to pair a tapered light blue jean with a velvet black and blue colorblocked blazer for our interview. And even that chic ensemble makes a statement. Like many artists before him, Natti's path has been full of colorful twists and turns, but it is one marked by his virtuosic command of music composition and a scrappy determination to be the true author of his work.

When Natti was just 17, he called the Marlton Hotel his first home in New York; as legend has it, the chic spot was both a brothel and a New School dorm during Natti's stay. As soon as he was in New York, he was was writing constantly, and playing songs in practice rooms of the Mannes School of Music and at parties. By 19, Natti was ready to leave school, becoming discouraged by composition teachers who literally told students that they would never write a hit song, while fully knowing his true potential.

Once he did leave New School, Natti hit the ground running as a performer on the downtown New York scene, booking himself shows at Pianos and the Yippie Museum Cafe. In Boston, he met Lance Horne through a mutually famous friend, Amanda Palmer, formerly one-half of punk-cabaret duo, The Dresden Dolls. As Lance took Natti under his wing, Natti gigged more around the city on the cabaret scene, learning the importance of composition, performance and impact.

"In my mind, no one works harder than New York cabaret artists to put on a show," he says. "They do everything from improv, to DIY outfits, engaging their audience. At its heart, cabaret truly is and always has been a form of resistance."

It can be argued that few artists work harder than Natti. And for Natti, now is definitely his time: "My friends have been joking with me for years saying that for someone who gigs as much as I do, that it's fucked up I don't have a proper record," he says.

OUT: What was the first song you ever wrote?

Natti Vogel: The first song I wrote was at age 11, when I scored a melodramatic student slasher film in middle school: it included this self-consciously cheesy ballad I wrote, called "Forevermore," with a ton of parallel tenths and contrary melodic motion. I made sure it sounded silly because I didn't want anyone to think I took myself seriously as a writer. I continued writing joke songs throughout high school and made my first home-recorded album, a mega-lo-fi rock opera, called Jelly! about a jealous jellyfish, as an assignment for Marine Biology class. Fun trivia: the brilliant Le1f and I struck up a correspondence on MySpace after he sent me kind words on Jelly!--particularly a track he liked, called "Cnidocyst Tryst."

Who was your first career inspiration as a queer artist?

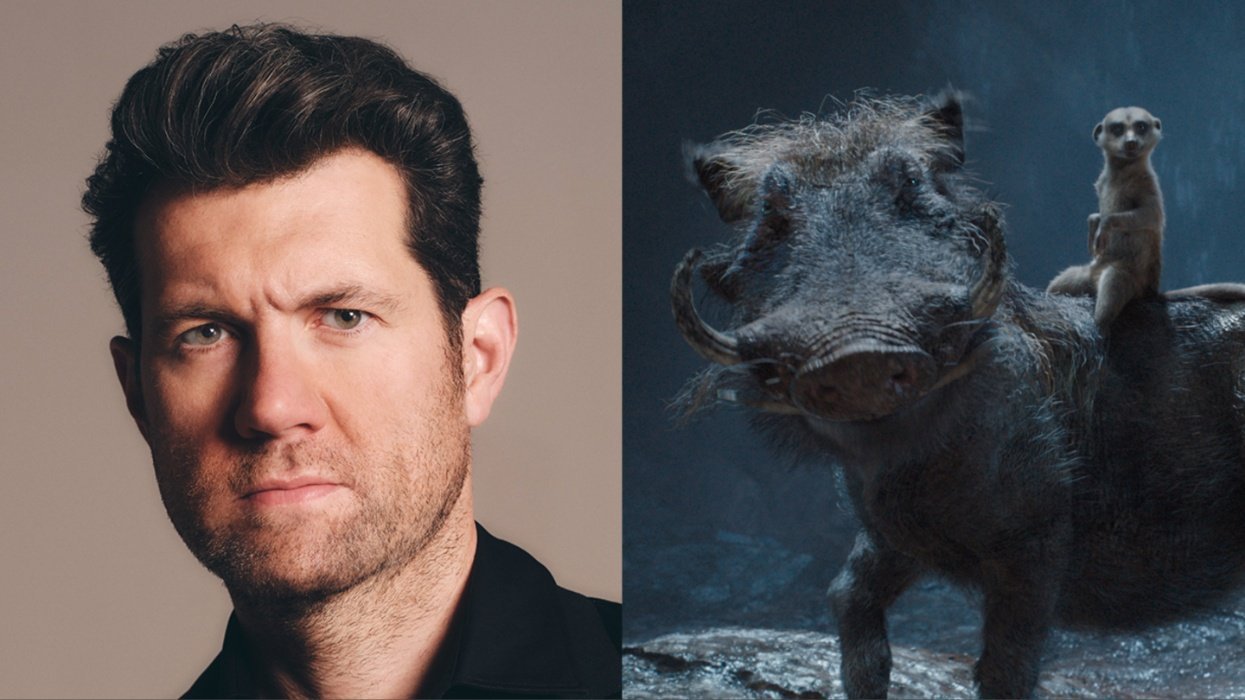

I feel like Ursula from the Little Mermaid, Hexxus from Fern Gully and Scar from Lion King were my first queer music icons. Though they were animated Disney characters portrayed as villains, they had a serpentine sensuality that felt frank and nurturing to me as a baby boy.

I wasn't able to identify with being a queer artist until later, at age 18. A dear friend of mine, now a major bridal couture designer Samantha Sleeper, had submitted a song of mine to the New School Battle of the Bands, which barely passed the censors, but we won by audience vote. After the Battle, my bandmates were off partying, and I walked alone to Cafe Esperanto--R.I.P. 24/7 cafes in Manhattan--on this weird pilgrimage where Rufus Wainwright's "Cigarettes and Chocolate Milk" happened to be playing. It was the first time I'd ever heard him, though I had heard of him and knew he was gay. I asked the waiter if it was Beck, cause it sounded like Beck but better.

It's the first time I felt really mirrored. My bandmates, my classmates, most of my friends were completely straight, but I just felt like Rufus sort of "got me." Like, "Oh, I know you bitch: all these slutty melismas, all this grandiose fantasy, the vocal leaps, the showy piano arpeggi, the decadence, that's me."

Talk about the title of the album. It feels obviously a little cheeky in several ways. The idea of "serving" is very queer.

Yes, I am serving you face, body and a whole bunch of other concepts surrounding interpersonal consumption: economic, sexual, emotional. "Moonshine Melody" is about saying no when closeted dudes try to serve you prohibition-era body, "Brown Rice" is about the behind-the-scenes self-esteem issues that come up when serving body in relationships, and so on. But this record is also about serving those who have been part of my core audience from the beginning, and serving some new ears what I am offering, which is a complete body of work I wrote from ages 22 to 25. I want to serve so much orchestral body, compositional body, literal body. Just know that if you come to my house, you are getting fed.

Saucy! And though the songs are catchy, you would shy away from calling this a proper pop album?

I mean, if it gets popular enough, it could be? I just know making it has been this messy, epic DIY thing for me and I just hope people like it.

Tell me how the release "Cannibal" fueled other songs on your album.

I first played "Cannibal" live after coming back from my first solo tour in China, and my colleague and dear friend Rafael Leloup immediately heard the whole orchestration in his head just from the piano part. When he sent me a MIDI demo of his treatment, I was jumping around my weird circus apartment for joy, like "this is my sound!" But orchestral pop takes a long time to make DIY, so fast-forward a couple years to its uber-glam single release party on the rooftop of Hotel Chantelle with full live orchestra, an open bar and cute costumes. No one knows that I was sleepless for a month in advance of that show. I didn't really have to press outlets, shuttling leftover, unopened bottles of gin from an office party to make it look like a Tanqueray sponsorship, enlisting my friend as the door person, ghetto-rigging everything. It actually worked, the place was packed, and it set the stage to be able to produce Rebecca Rojer's music video. Mind you, I am a utilitarian at heart. So, I was on this website where gentlemen can admire each other's nude form, right? I posted a picture my friend Najva took of me stomach down on a canoe with the caption "S.S. ASS", and that's how Colby Keller slid in my inbox. Instead of being like, "Hey, let's bone," I was like, "Hey, thanks, wanna be in my music video?" When it came out as a premiere on MTV, my grandpa, a Harvard professor was all like, "Congrats! Is that your butt we see?" And I had to think quick, so I told him the truth. I said, "Grandpa, I'm not at the stage of my career where I can afford a butt double." He was like "Well, did they spell your name correctly? Bravo." The momentum from that video helped me hustle to fund the other songs on the record, with help from the David Kassan Foundation and two older, more successful fans.

Aside from "Cannibal," your song, "I Don't Wanna Find the One" feels very radio friendly, while still maintaining what makes you compelling. Is there a story behind that song?

This was my conscious attempt to write a straight-up pop song. I figured, "I love pop music: I deconstruct it and reverse-engineer it all the time, it's time to get over feeling like the form is a limitation." Plus, to sort of mash-quote Ziggy Stardust and Cardi B: I could do with the schmoney. In writing it, I stuck to five chords and a rigid pop mold, but there is hella modal interchange, wacky rhythmic phrasing and a subversive message, so it ended up feeling 100 percent me. I have this image of me in a fierce black blazer and pointy suede shoes on a late night show popping my pussy out to this track.

The song that seems most like the wildcard on the record is "Moonshine Melody," which changes tempo and inverts structure a lot. Tell us about this track and how it speaks to your work ethic as a songwriter.

You're right about that. It feels like--along with "Brown Rice"--one of the boutique songs of the record that will introduce listeners to a more indulgent side of me, even though at the time I honestly thought I was writing my most accessible work. I workshopped this one a lot with friends and other musicians I admire and respect. I spent hours and hours, as I always do, on getting every second to be just right. And about songcraft in general, for me, it's always a discipline. Effort is a limited resource. There are things in life I will honestly never want to do. We all have to choose what we excel at, and what we can forgive ourselves for being idiots at. And for me, songwriting is like taking care of myself, like one would take an iron pill or pay the bills, both of which I've gotten better at doing in my twenties. I never begrudge the time I spend working on a song. Like, if I had to take care of a baby, I'd probably resent that baby, no lie. But never a song. It never feels like something I feel obligated to take care of, I just love it too much. So for "Moonshine," my ritual became jogging twice a day and poring over hourlong voice memos of material I'd rehearsed and recorded while writing it. It would scare me if I clocked all the time I spent on certain songs. But think of it this way: It's like the song itself did the diet, worked out a ton, and now it's ready to be a thirst trap

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right