Life for gays and lesbians in Russia is clandestine and convoluted. But the country is inscrutable to the West, so it may be impossible to seek civil rights advances like anything we’d imagine.

February 05 2014 9:30 AM EST

May 26 2023 2:38 PM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

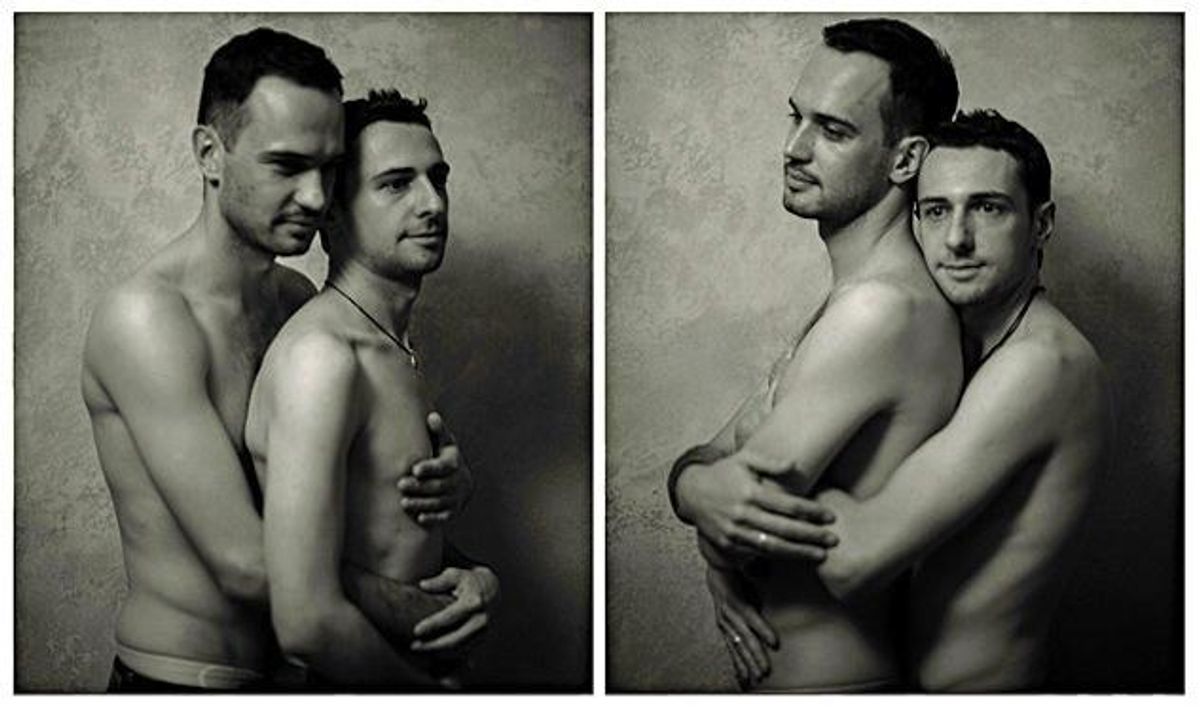

Above: Ghibi Shavgulizdze & Ortem Viktovskiy, Moscow, 2013. | Photography by Davide Monteleone

From 12 stories up I see the sign "Gay Bar Entrance" above the barbed-wire gates through which two gunmen have just fled. It's a night like any other in gay Moscow: some violence, some tears, and a cold rain. Beyond the railway station, the vast concrete morass of Soviet housing blocks extends into the horizon from the outer rungs of the city to the far-flung suburbs. To find a gay bar in Moscow without a guide is nearly impossible. The gay scene is a network of back-alley stairwells and unmarked doors. Storefronts are disguised as flower shops, trap doors lead to secret passages. There are only about a half-dozen such bars in this city of over 11 million, but that seems to be plenty.

With the West preparing to descend on Russia, determined to plant rainbow flags and deliver a message of solidarity to the country's troubled gay population, I have come on a hunch, unnerved by the media coverage that is either overly sentimental or sensationally victimizing. I've come for a glimpse into the ordinary lives of gay Russians, to understand what should be done to help -- if anything at all. I didn't expect to return with an answer.

Until this point I have not been frightened to be an openly gay man traveling through Moscow. Granted, I have two things working for me: I'm a foreigner and I'm in a cosmopolitan city. The fear only comes when I check the American newspapers and see headlines using words like "crackdown" to frame the violence here as a sort of government-driven bullet train to genocide, when I see my friends on Facebook raging about the tyrannous state of things in Russia. That's when I question my safety, when I use more discreet language in my emails, when I become suspicious of people.

Winter always seems to come too early in Russia. I sleep through daylight's afternoon cameo and drive an hour outside the city through a beaten landscape of shopping malls, scrap yards, gaunt birch forests, and a low sky to Ilya's gay dacha compound for Sunday dinner. Inside a privacy wall that gives the property a fortress-like quality are three identical houses, a communal sauna, a fish pond, and a chicken coop. Eight other gay families live in the village nearby.

Sergey is a journalist who has been writing for Moscow newspapers since the days of Soviet censorship. Like many gay people, he's "not in the closet, but also not out," largely because even in Moscow there's always the possibility of losing your job for being gay. Since the summer he has been dissecting the paradoxes created by the antigay propaganda law and the media, particularly the entertainment industry, for a Moscow daily.

"From every corner of this country, on every TV station, all you hear is 'gay.' Such public attention to this topic has never occurred in Russia," he says. "So many people are interested in gay items, even people who didn't think about this before. The people who started this antigay law have contributed not so much against, but for gay propaganda. It's a good thing."

We're by the fireplace, amidst a harem of young guys in loungewear basking about the dacha like stoned housecats. I've caught the eye of a chiseled young blond from Belarus, a soldierly beauty with shoulders like polished stone and a tribal tattoo on his arm. But he's shackled to Nikolai, a bald, extremely fat, extremely rich Russian man of few words who doesn't take his eyes from the dinner plate.

The first course stretches along the table: wild Siberian mushrooms, European blood sausages, salted sturgeon, salmon caviar, and homemade bread. Sergey has known Ilya since 1994 when Ilya opened Russsia's first official gay bar, and comes to this dacha every Sunday for dinner. He's an unassuming man in dark glasses who shares my passion for hypocrisy. The story du jour involves the recent Eurovision Song Contest. This year's compe- tition, broadcast from Sweden on Russian state TV, was officially sponsored by an LGBT organization, and the finale even featured an onstage lesbian kiss, but rather than refusing to air the show, an act that would certainly have caused civil unrest, the state-run network pretended not to notice.

Above: Katia Andreeva and Maria Krilova, Moscow 2013

"This gay propaganda law is absolutely, 100% a project for uniting the conservative electorate; I guarantee you won't see one case implemented under this law," Sergey says.

Ilya is partial owner of Central Station, along with a handful of other clubs in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and continues to be one of the country's three major players in gay nightlife. He's a solid man with a blond crew cut, cerulean eyes, and a paunchy, bulldog face. He brags about his parents, who were famous Soviet scientists, and his cooking, and the lithographs on the dining room wall. I like Ilya; he is warm and proud.

"Putin does not care about gays. The government only cares about maintaining power," he tells me one night as we cruise down Tverskaya Street in his red Mazda Miata past a canyon of grim housing blocks revamped in Vegas-like glitz. "This is about suppression. It's funny when the gays say, 'We have to go into the streets,' because other people cannot go into the streets either. It's not just a gay thing."

Back in the city, I take the metro to meet the publishers of the websites Gay.ru and Kvir.ru. The orderliness and precision of the subway -- a fraction of the size of New York's with twice the daily ridership -- is dazzling. Every 90 seconds trains arrive, dispelling commuters who march silent and beetle-like through buzzing, ornate catacombs of chandeliers and gilded mosaics.

Mike Edemsky, who goes by the name Ed Mishin, greets me with coffee and a bowl of wafers. His five employees have gone home for the day. The office is in a spare bedroom of Edemsky's seventh-floor apartment in a nondescript residential tower in the far northwest corner of the city tucked behind a quiet street in a neighborhood of working families and pensioners. After the gay propaganda law passed, Kvir, which means "queer" in Russian, a print magazine with a monthly circulation of 35,000, was pulled from bookshelves nationwide and now lives on as a website.

Vlad, its editor-in-chief, looks a bit like a handsomer, able-bodied Stephen Hawking and Edemsky is grey, equally academic-looking, standoffish and wiry. Vlad's embarrassed of his struggling English, though it's still far better than my Russian, and insists Edemsky does the talking for him. During Soviet times the gay scene, absent any legal protection, looked virtually the same as it does now: a network of secret doors and closed parties. People talk about a costume designer for the Bolshoi who held salons in his apartment where he'd sew gowns for his friends and hold secret drag competitions. It was illegal to print the word homosexual, let alone have a gay-oriented press.

Above: Russian and U.S. journalist and author Masha Gessen (right), and family in Moscow.

Gay.ru began in 1997, when many gay Russians say the nonchalance of a newly freed people made life easier for them. They were also decadent years, with experimentation and few questions. It was a decade when average Russians believed gays existed only as a strange, bougeois Western phenomenon.

Today Gay.ru gets 50,000 daily hits, Kvir around 20,000. About every six months they might receive a harassing phone call. After the passage of the law in June, a government oversight committee investigated Gay.ru as a gay propagandizer but decided, since the site has an "over 18" sticker on its homepage, it could continue publishing whatever it wishes.

"Maybe tomorrow morning somebody will decide, 'Let's make this law more effective,' and in one hour every gay club in this country will be closed and all media shut down, and it will be absolutely legal because they have this law," Edemsky says. "We are sitting in the hole and waiting. Will the cat decide to go into the hole and eat the mice, or will it decide to keep us maybe for tomorrow's dinner?"

Tucked behind an apartment building about a kilometer from the Kremlin, a small glass storefront advertises flowers for sale. At night, the floor lifts up, revealing a stairwell that leads down to the gay club Nashe Kafe.

The club is a narrow rectangle with a small dance floor in the rear and a bar cut from the wall where a bartender rests his chin on his palm like a disaffected civil servant. The walls are black and the lights are blue, lavish red curtains frame the dining area, and the crowd is festive in silk shirts gyrating to Russian pop music. At all clubs, between shots of vodka, the gays, like their straight counterparts, eat meat and caviar all night long.

From a Muscovite's perspective the scene is rotten with provincial tourists from far-flung parts of Russia, recognizable in the ways all country people are: soft bodies, gnarled teeth, outdated haircuts, and tender smiles. From Volograd to deepest Siberia they touch down in droves, many of them very young and traveling under the guise of a cultural trip to the capital.

For the rest, an overarching joylessness, bred by isolation and familiarity, prevails. There are the cliques, petty prejudices, fistfights, and high drama that will be familiar to anyone who's spent time in rural gay bars in America. People can be aggressively inviting and highly sensitive. They are both ashamed and entranced by foreigners. They love drag queens. Darkrooms, where patrons elope for sex, are more public amenity than novelty.

A high degree of emotion is set free in the secret labyrinth of gay nightlife. There was Amin, a 21-year-old Muslim sex worker from Chechnya, a dapper, muscular, self-conscious little charmer with black eyes and acne-kissed cheeks who twice cried on my shoulder in the downstairs lounge at Central Station, a diner-like space varnished in Soviet manila. Both times were because a man had just rejected him for sex -- not the paid kind. And Tatiana, the 40-year-old divorcee, her only friends a gaggle of 20-year-old hairdressers, also cried on me while recalling her ex-husband, and spent the night asking strangers for beers.

I was invited here by Vince, a preppy, clean-shaven American who is out tonight with three expatriate friends from Western countries. Vince and his friends have lived in Moscow for nearly a decade, have white-collar jobs, and are in their thirties or forties. I stand in a circular formation with the guys listening as they discuss their gay Russian lives for my benefit.

Vince: "They don't need a gay pride. It's way too early to talk about a gay pride when most people aren't even out to their closest friends."

Mark: "Don't you think there is more acceptance of us being gay than if it were one of their own? Because, as Westerners, they already think we're weird."

Vince: "A lot of them don't go out to the gay bars, they don't want to see someone they know. I also think a lot of it is snobbery. They'll go to gay bars in foreign countries but not at home."

Paul: "I'll tell you right now, they're all bottoms and they're all under 25 and they've all got amazing bodies because they don't eat."

Mark: "One of the reasons they're all under 25 is because the people who are over 30 are all weird, because they're from the Soviet Union, they're all cagey."

Zach: "In every Russian relationship there has to be a power dynamic, one who is the man, one who is the woman. You're never on equal footing."

Zach: "The relationships are fucked up and they are fraught with complexities."

Mark: "Dating a Russian has its own set of joys."

Vince: "And notice none of us are doing it."

We order a round of beers and the bartender changes the music from a Russian pop song about not having Wi-Fi to Madonna. Vince leans into me, "He did that because we're here." The dance floor clears in a heartbeat and the rippling silk shirts mope back to their meat plates.

Zach: "Most of the people in this country are probably secretly tolerant toward gay people. But they don't want a parade -- gay people don't want a parade and straight people don't want a parade. A small group of people have hijacked the LGBT movement, and it's all ego-driven. Things change quickly in this country, and they are extremely rational, but things don't get done here by having a parade."

Vince: "You have a gay bar that is relatively openly gay just outside the Kremlin... That's activism."

Zach: "Russia is really good at enacting laws, but the people just do whatever they want. This country is lawless. There is a disconnect between society and politics. The propaganda law is disgraceful in what it represents, but the practical effect is still yet to be seen."

Mark: "Gay people have it so much worse in other parts of the world, but because Russia is a white country and we think we have white people figured out -- how they're supposed to behave -- we put European standards on them that simply don't apply. If you scratch the surface here, it's way more like China than Europe."

Vince: "And there's this huge rebirth of the Orthodox church here. I fucking hate it. This is used as justification for a lot of these laws."

Paul: "That's the whole hypocrisy of Russia. Religion was fucking banned, the most beautiful churches in this country were warehouses, left to fucking rot, and all of a sudden there's this fucking rise of religion."

Zach: "If you don't have a doctrine to subscribe to as a national identity, you have to create it. And if you wipe out 70 years of Soviet history, you need to go before then. You say, 'What were we before this?'"

Mark: "This is a country that is 96% Russian Orthodox and 100% atheist."

Zach: "The thing that's great about Russia, the reason we're all here, is that it's fucking fun. It's crazy, it's exciting, Russian people are off-the-wall. They're great and they're smart."

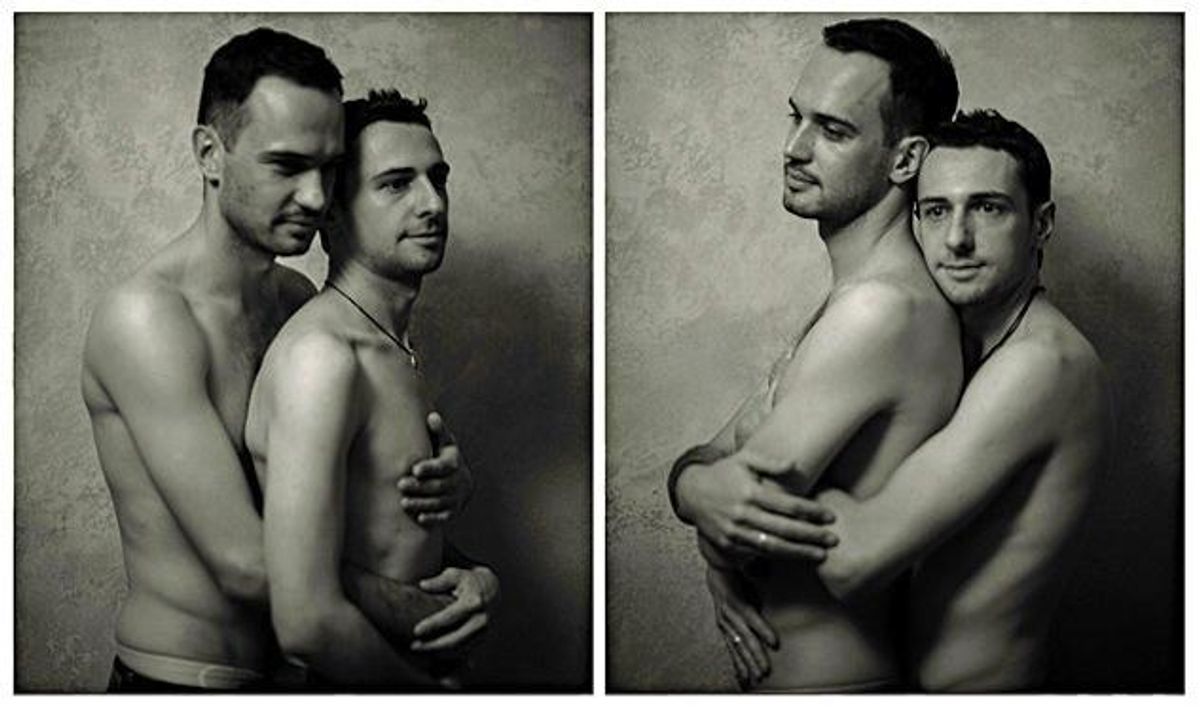

Above: Kostantin Tyutrin and Nikolay Nedzelskiy in Moscow, 2013

The night after the shooting at Central Station I phone Ilya. There were no injuries. The shots were fired into a wall at 5 a.m. when about 500 people were still inside the club. The police are investigating, but for Ilya there's no mystery: The purpose was coercion, not bloodshed. His landlords have been trying to strong-arm him into breaking his lease, which expires in 2017, in order to sell the property to a developer.

Three months ago they installed the large yellow sign that reads "Gay Bar Entrance" in Russian, and then a second sign, in neon pink lights: "Gay Bar," with an arrow pointing to the door. This was meant to intimidate customers. They intended to squeeze out Ilya financially. Instead, the signs have become a running joke for the hundreds of people who come here each week, and they're overlooked by the thousands more who pass by every day or wait for the bus across the street.

The following week there will be a second attack, this time involving poison gas, but again there will be no injuries or fatalities. Although being a gay establishment makes Central Station more vulnerable to brazen vigilantism, Ilya insists this has all the hallmarks of a business move, not a hate crime. He also has faith the police will take this investigation as seriously as any other, which may not say much.

Margret has a thing for cops. In Russian society, this makes her more perverted than any homosexual. She and I glide on a Muzak cloud through the GUM shopping mall past Louis Vuitton and Tiffany, looking for a place to eat and discuss genocide.

"There's nothing more preposterous than absurd, beastly homophobia in a country where the majority was brought up by same-sex couples, by mom and grandmom," she says.

Margret is a traumatized, petite, copper-haired woman who's lived in six war zones and done humanitarian work in over 50 countries. She's like a shell-shocked Amy Sedaris. If you crack a small joke she blinks and checks out the room before laughing.

"I'm surprised you showed up," she says to me, having already scolded me once via email for lapsed responses.

Born in the U.K. to diplomat parents (her father was the head of the Anglican church in Russia) and a demographer by training and criminology expert, Margret came to Russia just after the second Chechen war to address the sexual violence epidemic, though officially speaking there's no such thing, since the police don't keep rape statistics.

"There's no mystery about Russia's soul," she says. "It's a ghetto of troubled teenagers. If you go to a suburb of Paris populated by immigrants, or some ghettos in the United States, you see the exact same mentality. The question here is why is it on the scale of a whole nation?"

We've found a cafeteria where she's taken a sausage and a pickle, while I settle for a cup of coffee, and we go to a small table.

Above: Niuta Ginsburg and Lena Mastepanenko, Moscow, 2013

"Russia is dying," Margret proclaims. "It's like in Africa: They're all very religious and then they go and kill each other." She sees the level of criminal violence in Russia as a decentralized genocide. Ten years ago, the chief research gynecologist in Russia estimated that 250,000 women had become infertile because of sexual violence; the country has the world's highest abortion rate. Because there is embarassment around sex and a stigma in buying condoms, abortion is the most prevalent form of contraception. This also explains the country's mind-boggling HIV statistics: the infection rate is twice as high as the United States and, according to numbers released in December, 58% of cases result from intravenous drug use, 40% from heterosexual sex, and 2% from "other," which includes gay sex.

"I've traveled a lot around Russia, and the average 20-year-old, she's gone through two gang rapes and two abortions," she says. "So when gay friends tell me it's so hard for gays, I say it's not hard for gays. It's hard for anybody."

Margret moonlights as one of the most notorious gay rights activists in Russia, a movement that is dominated by heterosexuals, foreigners, and westernized Russians. She makes a hobby of sexually harassing police officers, whose slogan translates to "the competent organ of the state." She delights in asking scores of officers at political rallies just how competent that organ is.

"Nothing scares them more than being loved, because nobody has ever loved them," she says. Officers frequently get drunk and leave bawdy comments on her blog. In person they threaten to rape her, but they blush and bolt when she shrieks with delight.

It is here that I understand the incredible shortsightedness of gay civil disobedience in Russia. The country is maiming its women on a scale that connot be compared to the kind of violence seen in sporadic viral videos of neo-Nazis torturing gay people. Yet when the Olympics come there will be, inevitably, some activist waving a rainbow flag on camera. The West will cheer and pat itself on the back, while the whole of Russia will say, 'What a nice flag. I wonder what it means?'

And while it is not only women who are being slaughtered in Russia, it seems that, for a country which has never appreciated the need for a civil rights movement (after all, the premise of communism, falsely it turns out, is to treat all people as equal), protecting women seems like a viable, digestable starting point for making life better for all. If the country can be convinced to protect one population, it can be convinced to protect others. Until then, the most effective action gay people can take will occur on the grassroots level, by simply coming out to their friends, families, and coworkers. This is how change happens and continues to happen in the United States -- not with a parade, but with a tap on the shoulder.

I excuse myself to go to the bathroom. When I return, I notice the thin man in the suit who was eating lunch at the table behind Margret is now one table closer, with a new plate of food. He's been here for our entire two-hour chat.

"Do you recognize him?" I whisper.

She considers this. "Doesn't look like FSB to me," she whispers back. "But sometimes they use outsiders so you can't recognize them." The man at the table gives us a sidelong look and slowly chews his mashed potatoes. I'm convinced it's time to go, but Margret laughs it off. "They won't do anything to you," she says, "They just want information."

We head to the street and I abandon an annoyed Margret at the metro and meander a quarter-mile down the way to a gift shop where I purchase a coffee mug depicting a rifle-toting, bare-chested Vladimir Putin and a refrigerator magnet that reads "I Love Moscow." I thank the lady and, without looking behind me, go through a passageway to the Russian state library. I take self-portraits in front of the statue of Dostoevsky, to appear as dopey and unthreatening as possible. I admire the concrete and photograph the lawn. I look over my shoulder. The thin man in the suit is nonchalantly there, gazing off into the granite sky.

DAVIDE MONTELEONE started his photographic career in 2000, moving to Moscow the following year as a correspondent for agency and publishing house Contrasto. Since 2003, he has lived between Italy and Russia, working on long-term projects. Monteleone has published three books: Dusha, Russian Soul (2007), La Linea Inesistente (2009), and Red Thistle (2012). He has won numerous awards for his work and shoots for a wide range of prestigious magazines and foundations.