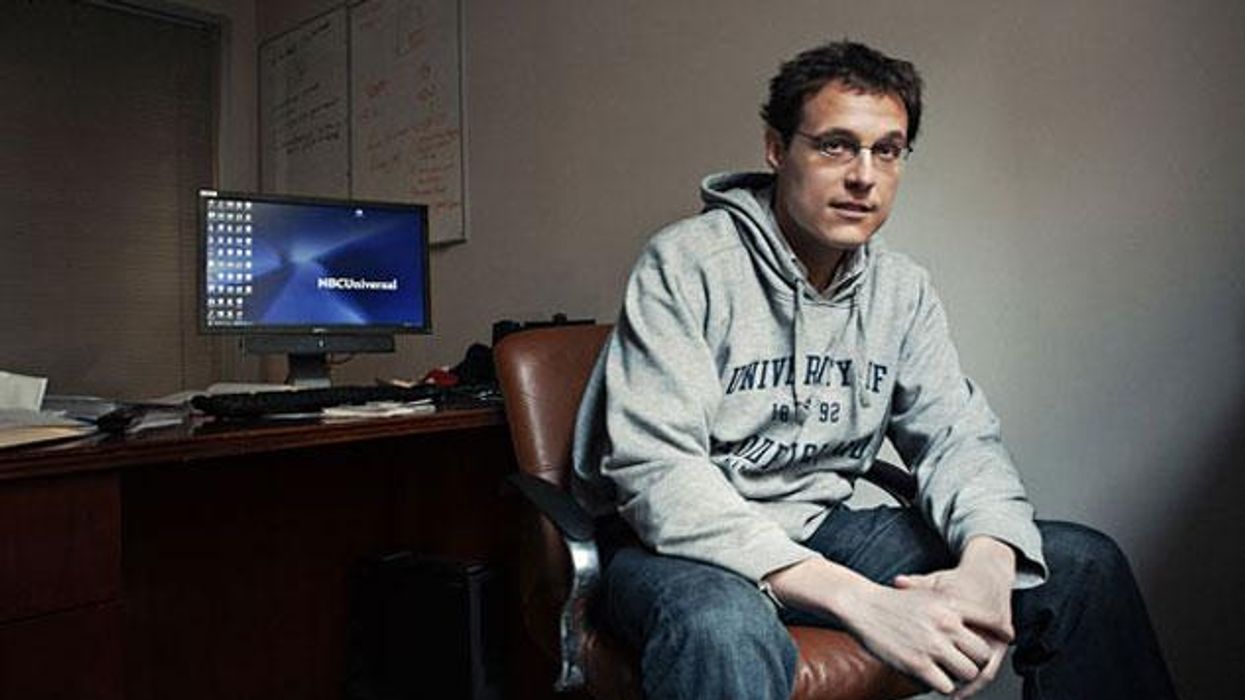

Kornacki is still nursing a hangover when we meet for dinner at a Midtown pub the next day. And that's OK, because it's Kornacki's day off. When you spend your week furiously mapping out a newscast only to wake up at 4:35 a.m. every Saturday and Sunday to shoot it, you deserve some downtime.

A lifelong politics wonk, Kornacki inherited the early morning slot from Chris Hayes, another bright young thing on a roll, a little over a year ago. Hayes made the show a hit in the hinterlands of weekend morning television, especially among the kind of millennial viewers who make advertisers drool. Kornacki's now building on that momentum.

That he's doing so through a mix of nerdsmanship and old- fashioned shoe leather, as opposed to partisan zeal, makes him a curious specimen of cable news, where the loudest, most opinionated pundits tend to win the most eyeballs. "He's doing something unusual on TV," says Josh Benson, a close mentor and one of Kornacki's former editors. "He's a natural facilitator of conversation, but at the same time his reported analysis is so good that he's actually leading coverage of national stories."

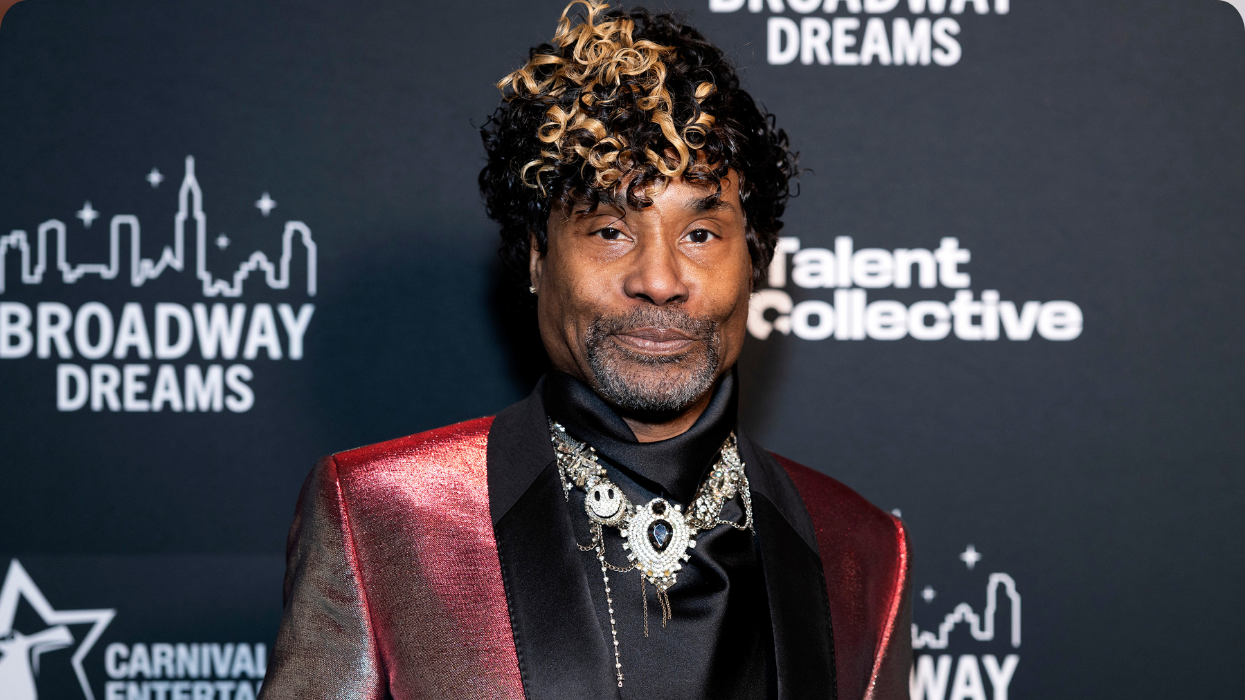

Kornacki fills another role: He's one of a growing lineup of media figures who are dispelling the tired myths of what it means to be a gay man or woman. Can you be gay if you're a politics nerd who loves sports? The answer is yes. (See also: Nate Silver, the star statistician who now has his own slice of the ESPN empire.) You can, in the same way you can be gay if you're a muscular dude like Thomas Roberts who never looks out of place talking current affairs with resident MSNBC man's man Joe Scarborough. Or if you're a glamorous morning show star like Robin Roberts, whose audience on ABC largely consists of Middle American housewives. Or if you're a stylish, flirty prime-time anchor like Anderson Cooper who also parachutes into war zones and natural disasters.

"Most people used to be exposed to only a select cross-section of gay people," says Kornacki. "But the atmosphere has changed so much, and so quickly."

At 6-foot-2, with flawless skin and teeth that look like they were ripped from a Colgate commercial, Kornacki is nothing if not telegenic. Lots of girls would love to bring him home to mom and dad. But that was never in the cards.

"I was the All-American kid, or so I told myself -- good grades, never in trouble, bright future, well-respected by my peers," Kornacki wrote in a coming-out essay for Salon in November 2011. "After a trip to Cape Cod with a friend and his family, the kid's mother said her favorite moment was watching 'straitlaced Steve' struggling to make sense of all the hedonism around him when we drove out to Provincetown. I remember seeing drag queens and men dressed in skimpy attire and thinking to myself, Get me out of here so I can watch a baseball game."

It wasn't until his sophomore year of high school, at a basket- ball game where the guys he was with were ogling cheerleaders, that Kornacki began to wonder: "Why wasn't I looking at the cheerleaders that way? And why was I sometimes noticing the players instead? My heart rate quickened and a thought surfaced: This is what it means to be gay."

The seeds of Kornacki's TV news career were planted at an even younger age. "The earliest thing I ever wanted to do was just be, like, the next Brent Musburger," Kornacki says, refer- ring to the legendary sportscaster. The politics obsession was full-blown by the time of the 1992 presidential race; 12-year- old Steve was utterly crushed when Massachusetts Sen. Paul Tsongas lost the Democratic nomination to Bill Clinton. "He's always rooted for the underdog," says his sister, Katie.

Kornacki's path to the small screen was circuitous. After graduating from Boston University in 2001, he rented a car with two friends and drove to Los Angeles. (An inveterate hypochondriac and notoriously picky eater, he also has a fear of flying.) There they booked an extended stay at a Days Inn. Kornacki counts game shows among his various obsessions, and he'd hatched an ill-conceived plan to make money as a perennial contestant. After many unsuccessful tryouts for The Weakest Link, Win Ben Stein's Money, and Smush, he came home empty-handed and started writing news copy for a regional TV network. Dozens of applications for a full-time- reporter job later, he finally landed a gig in 2002 at a New Jersey politics website. He moved on to jobs at Roll Call, The New York Observer, and Salon, where he was hired in February 2010. Guest appearances on the cable news circuit put him on the radar of MSNBC brass. By 2011, he was a regular on The Rachel Maddow Show and The Last Word with Lawrence O'Donnell.

Behind the scenes, however, there was some inner turmoil. Kornacki had finally found someone he was ready to be in a serious relationship with -- he just wasn't ready to tell everyone that the someone was a guy. His Salon piece was both an intensely personal public disclosure of his sexual orientation and a bold attempt to save a relationship that had crumbled under the weight of his closeted life. He'd written the story and filed it to his editor but there was one caveat: He still had to tell his family. He wanted to do it in person, and had a weekend to pull it off. With his sister's help, Kornacki hatched a plan to meet his parents -- a social worker-turned-homemaker and an executive search consultant -- in Hartford, Conn., a midpoint between Kornacki's apartment and their home in Brunswick, Me. As bait, he planted a white lie about work-related news. When the four sat down in a restaurant that afternoon, Kornacki passed around a copy of the text.

Photography by Clayton Cubitt

"I've read stories from people who say they always knew they were attracted to the same sex, or that they figured it out at a young age," his article began. "I'm not one of them." Kornacki's pulse raced as his parents pored over the confessional. After a few minutes, his parents broke the silence with words Kornacki was hoping to hear: "We're proud of you." His shoulders felt lighter. "He was so careful not to let anyone in on this secret," recalls his sister. "Whenever you keep something a secret for so long it becomes bigger than it really is. There was a lot of relief that he was finally comfortable enough to be open with us." The icing? Kornacki's imperiled relationship got a second try. (They split upa gain six months later, but remain friends.)

Kornacki was happy at Salon, where he enjoyed the freedom to write about all manner of political arcana. But the more cable news hits he did, the more he hoped it would turn into something permanent -- "Or at least some kind of paycheck that would get me out of debt," he says. Then, in June 2012, Kornacki did get some big work-related news to share with the folks: MSNBC hired him full-time as part of the cast of a new afternoon program called The Cycle. It was a chance to prove his value as a talking head, and he nailed it. Eight months later, when Hayes made the jump to prime time, MSNBC tapped Kornacki to host Up.

Kornacki immediately distinguished himself as an idiosyncratic anchor. In addition to his encyclopedic knowledge of political history, he also has a propensity for monologues. "He can bring you from zero to 200 miles per hour in a very succinct amount of time, and in a super heroic way that I'd put up against anyone else on our network including myself -- or anyone at any of the other cable news networks," says Rachel Maddow. (Along with Kornacki and Roberts, Maddow is one of MSNBC's three openly gay hosts.) "I think he really is the next big thing."

On the morning of Jan. 18, Kornacki's ascent went from measured to meteoric. Ten days earlier, the "Bridgegate" scandal that was engulfing New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie had erupted into the national media. Kornacki had been covering the saga closely. Now he was about to blow it up even more with a major newsbreak of his own: He had learned that the mayor of Hoboken, N.J., was accusing Christie's lieutenant governor of bullying her into a development project by threatening to withhold Hurricane Sandy relief funds. Pen in hand, sleeves rolled up, eyebrows raised, Kornacki delivered his scoop with the giddy intensity of someone who lives and breathes political drama. The segment went viral, ricocheting around the media sphere and eliciting head- lines for much of the following week. "Steve Kornacki...is at the center of one of the most consequential political stories of the year, [with] the potential to eliminate Chris Christie as a contender for the Republican nomination for president," gushed the local newspaper in Kornacki's hometown of Groton, Mass.

Career-wise, Kornacki isn't entirely sure what the future holds, although he confesses he's not enamored of the idea of spending his life waking at the crack of dawn every Saturday and Sunday. MSNBC President Phil Griffin says Kornacki's ratings are strong when he fills in for the network's evening hosts, most of whom also started out as humble contributors. For his part, Kornacki says he still has a lot to learn before he's ready for prime time, and a lot more work to do with the show he already has. "I don't want to be on TV for the sake of being on TV," he says. "I think we're still kind of figuring out what we are, and what we can be."

Kornacki wrote a weekly politics column when we worked together at The New York Observer in the late aughts, one that offered a sharp dose of inside baseball for the power brokers who read the paper. He struck me as quiet but affable, maybe even a little shy -- nothing like the commanding, loquacious, presence I'd see on my TV screen a few years later.

He can be really funny, too. In a hokey recurring bit called "Up Against the Clock," he pays homage to the classic game shows that have capti- vated him since childhood. "I would watch these shows at 8 years old and feel like the most important thing in the world was about to play out," he says. "The drama, the pace, the race against the clock..." The segment is deliciously campy -- a paradox for some- one who once recoiled from P-Town drag queens. Kornacki usually plays host, but in a special Jan. 4 installment, those duties were handed over to a graying Marc Summers, of Nickelodeon's Double Dare fame. Kornacki put on his contestant cap, laughing sheepishly to the sounds of '70s-esque theme music and the hyperbolic announcer who introduced him: "He's come a long way since wearing the same sweater three times in a week on national television. Here is a clearly uncomfortable Steeeeeeeeeeve KooorNACKI!"

Coming out was a huge change for Kornacki, but it didn't change who he is. He's still that guy you see watching baseball with his buddies in a bar. He's a sporty prep who loves comedies like Airplane, has musical tastes that skew more Motown than modern and can drop knowledge about Mondale and Hart's 1984 primary battle as if he hadn't been 5 years old at the time. This makes Kornacki precisely the type of guy who does not match the reductive image of a guy who's into other guys.

"I'd say the old stereotypes never really applied," Kornacki tells me when I ask him about this contradiction. "People who don't necessarily fit the stereotypes now feel less or no pressure to conform. I think of the small town I'm from and wonder how things would have turned out if I'd been born, say, 20 years earlier. I'm not sure I would have reached adulthood with a willingness to even start exploring this side of me, and I can imagine ending up getting married to a woman, having kids, and settling down just because that was the only thing to do."

For someone who spent nearly 15 years suppressing a core part of his identity, Kornacki finally feels comfortable being himself in every aspect of his life. "The biggest revelation has been just how much of a nonissue this is to just about everyone else," he says. "It used to be that when I was around people, I was constantly on guard not to say or do anything that would make them suspect I was gay. It was a little scary to realize just how ingrained in me that kind of deception was. It's a pretty big relief not to think like that anymore, and now I understand what I just couldn't believe for all those years: that it really isn't a big deal."

Photography by Clayton Cubitt