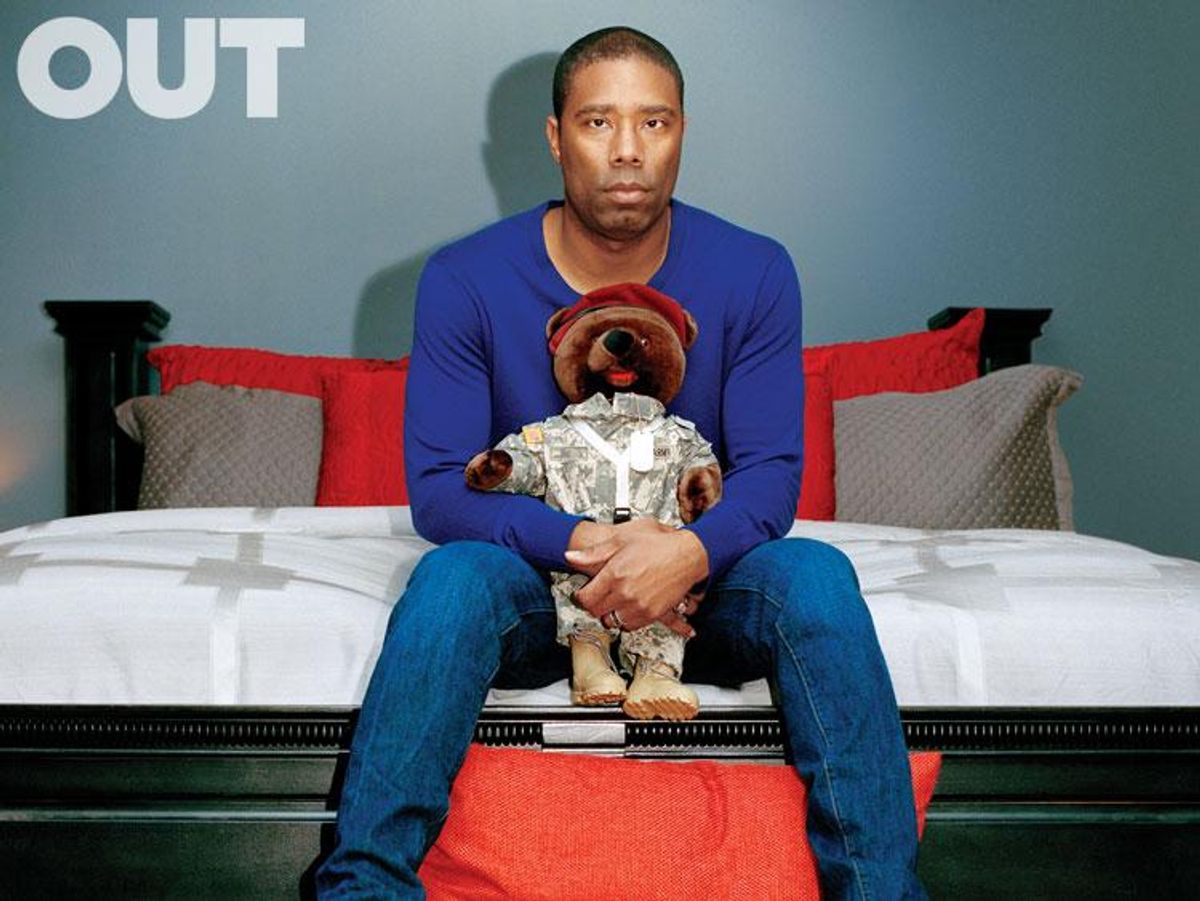

Pictured Above: Alex Teal believed his future with Stephen White was secure, now he says there's nothing left for him in Greensboro, N.C. | Photography by Zachary Krevitt

On November 8 of last year, Garry Gupton entered Chemistry Nightclub, shortly before the first drag show of the evening had ended.

"He seemed uneasy," recalls Jim Olive, a small man with striking blue eyes. Olive has worked at Chemistry since it opened two years ago. "I went up and introduced myself, and asked if he'd been to Chemistry before," he recalls.

Gupton, it turned out, was making his maiden voyage, not only to Chemistry, but also into the gay scene.

Driving down Spring Garden Street, in a residential neighborhood of Greensboro, N.C., it's easy to miss the single-level building, which looks more like a BBQ restaurant than one of the city's most popular gay clubs. The entrance leads straight onto the dance floor. To the right is a stage that hosts drag performances and go-go dancers. In the back, a U-shaped bar is overhung with TV screens, one tuned -- permanently, it seems -- to the Food Network, the other to the CW. The room is scattered with cocktail tables and a few love seats.

Chemistry Nightclub is a run-of-the-mill spot that could be in Anytown, USA, but for Gupton it was something else: his first time exploring a gay bar. To mark the occasion, Olive poured Gupton a drink and gave him a tour. It was still quiet enough to move easily through the venue.

Eventually Olive and Gupton made their way to the back porch bar, where patrons hang out smoking and drinking. There, Gupton caught the eye of a drag performer, Kymberli DeLorean, who had just finished a number. The two connected, and Gupton quickly settled in next to her. "Nothing about him seemed odd. He was normal," she says.

As the night wore on, Gupton kept up a steady pace of drinking. DeLorean and her friends who arrived later would ultimately ditch him, leaving him alone at the bar.

And then Gupton met Stephen White.

On the security tapes supplied by the nightclub, the moment of their meeting seemed ordinary enough. The bar was near closing and Gupton -- a younger, stocky guy with light facial hair on his cheeks -- appeared reluctant to leave. He tried flirting with one of the other bartenders, leaning over and shaking his hand many times, even whispering in his ear. The bartender, used to these kinds of come-ons, was cordial but detached. Gupton eventually left the front bar to float around drunk, attempting to talk to whoever seemed interested.

During all of this, White sat at the bar, entertaining another younger man, who eventually kissed White on the cheek and disappeared, leaving him alone at the corner of the bar until Gupton returned.

At 2:12 a.m., Gupton and White were among the last people at the bar. After Gupton finally introduced himself, White shook hands with him, and they hugged. Before long, they were deep in discussion. Their subject was that most reliable of gay conversation starters: coming out.

Olive was closing down the front bar for the night and stood close by. "I had my head down in the beer cooler, and Steve said, 'Isn't that right, Jim?' " he recalls. "And I pulled my head out of the beer cooler and said, 'What?' "

White leaned in closer to him at the front bar: "It's OK to be who you are, isn't it?"

Olive, now interested, stopped cleaning and said, "Yeah, but it depends on if you're comfortable with who you are. If you are comfortable with who you are, then yes, it's OK to be who you are."

Shortly after, the bar lights came up, and White asked Olive to call him a cab while he finished his drink.

Olive, who has made a habit of getting to know everyone who comes to the bar, would typically walk people to their cars, but tied up with cleaning, he said goodbye at the door. Hugging Gupton, he asked, "So you hanging with my friend Steve tonight?" Gupton replied that he was. "Take care of him...I like Steve," said Olive. Gupton nodded and left the bar with White in a cab, heading for the Battleground Inn.

Two hours later, fire alarms blared through the inn. Garry Gupton was found and arrested in the parking lot, charged with assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill. White was rushed to a hospital, where he'd hover between life and death for nearly a week, with 52% of his body covered in burns, before finally giving up the battle.

Kymberli DeLorean first found Garry Gupton, White's alleged murderer, to be a "genuinely cool person."

Alex Teal is tall, with glasses that seem glued to his face. In a Greensboro cafe one afternoon, he places two large photo

albums belonging to White across a table, and invites me to browse through them. Arrayed through those pages is a photographic

diary of White's life, from graduating boot camp to saying goodbye to his parents as he prepares for a stint abroad.

Part of White's time overseas included a stretch in South Korea, where most of the photos are not of White, but of other men -- men wrestling in barracks, men grinning at the camera, men lounging in armed vehicles. In the images of men in male social spaces, like the Army, you can sense something more -- something that White would repress for two decades.

White grew up in a conservative family in North Carolina. Until he signed up for the Army, following in the path set by his father, Greensboro was all he knew. After spending four years in South Korea, he returned to Greensboro to attend college, but no sooner had he graduated than he was back in uniform, first as part of the U.S. Border Patrol, working the U.S.-Mexican border, and later as an air marshal. Then, in 2005, on the eve of heading to Iraq to take up a new job with Blackwater, a private security firm, he told his family that he was gay.

To White's surprise, coming out wasn't as dramatic as he had feared. "His mom and dad were OK with it; his sister and her family were OK with it; and his brother who lives in New Jersey was OK with it," Teal says. "But the religious members of his family were not."

As with many gay men, White's fear of being perceived as weak or effeminate had pushed him to overcompensate for years -- leading him to act out a version of hypermasculinity as a disguise. "Stephen was the alpha male of the alpha males," recalls Teal. "He would chase down drug smugglers and arrest them and whatnot."

But when White realized he couldn't hide any longer, he opened the door and stepped through it to find that nothing had changed.

"They just saw regular Steve," says Teal, adding that White's sense of relief after coming out became an impetus for making a difference for others.

"His dream was to start a nonprofit helping guys like himself. Before 'don't ask, don't tell,' gays in the military didn't have relationships. They didn't tell people they were gay. There are some guys in the military still like that. Those were the kind of guys Stephen wanted to target."

White had only been in Iraq a few weeks after coming out, working as a private contractor, when he was almost killed during a mortar attack.

"Freak accident," says Teal. "There was incoming mortar fire, and they went to the closest bunker and closed the door. The mortar came down the stairs, blew the door off the hinges, killing one of his buddies right next to him. The guy's body fell on top of Stephen, and that's how he survived. The door and the guy's body took the brunt of the blast, but Stephen took some of it too. His jaw was partially off his face, legs smashed, arms smashed. They thought he was going to die."

But much to the surprise of his family and the doctors treating him, White survived. He returned to Greensboro months later, on disability and racked with trauma.

Before meeting White, Teal always knew he wanted to end up with another man from a military family, like him. "Army guys just get each other," he says.

Teal fell in love with White from a distance -- "a year and a half before he knew who I was" -- shortly after White returned from Iraq. He would see him playing pool and heard about his armed services background, but resisted approaching him after discovering that White had a boyfriend. That changed later, after he was told that White was newly single again, and things evolved swiftly from there -- if not always smoothly.

On November 8, shortly before White headed to Chemistry for his fateful encounter, he and Teal had dinner at Longhorn Steakhouse, one of White's favorite places. The purpose was to talk about White's alcoholism, a growing issue that had prompted them to put their relationship on hold at the beginning of August.

"We were talking about our next steps in life. We were talking about us, and how we both wanted to be together," recalls Teal. During their break, the two men had continued to sleep in the same bed, and spent ample time together. They had also agreed to keep their relationship open, but during supper they decided they were ready to take the next step towards marriage, which had just become legal for same-sex couples in North Carolina.

However, before that could happen Alex needed Stephen to get help with his drinking. White agreed. "He said, 'I want to keep you. I want to get married,' " says Teal. That Saturday night after dinner, Teal pushed White to go out one last time while he went back to their home. It was to be White's last night on the town before starting a new, sober chapter of his life.

Hours later, Teal awoke around 3 a.m. to find White hadn't yet made it home. At first he thought that perhaps White had gone to an after-party and would soon return, but after calling White's phone several times to no response, he suspected there was something wrong.

Sometime after 4:30 a.m., Teal heard the sirens.

Poolbuddies of Stephen White; bartender Jim Olive; Chemistry Nightclub owner Drew Wofford (right)

On his Facebook page, Garry Gupton's interests include women, Ford Mustangs, Ohio State Football, and quotations from the Buddha. On the hookup app Grindr, he is known in his neighborhood for having a blank profile, but sending a picture of his face with a "hey" to many people over the past year.

Gupton, who had a job with the Greensboro Water Resources Department, had attended Southeast Guilford High School, where he was allegedly often bullied for being odd, according to one of his classmates.

Aside from a simple assault charge in 2007, Gupton had no history of violence, and was described as a "good guy" by friends. This matched the initial impression of Kymberli DeLorean, the drag queen with whom Gupton spent a good portion of the evening.

"He was a genuinely cool person -- interesting," DeLorean

remembers. "You could tell he felt out of place, but through our conversation he got comfortable. I asked him if he was gay, straight, bi -- 'what are you?' And he said, 'I don't really follow labels, but I have never been out to a gay bar. This is my first time.' "

Gupton also told DeLorean that he had never had sex with

another man before, and it seemed he was ready to change that. But things shifted as Gupton continued to drink. Finishing her second show of the night, DeLorean returned to find a different man. "It was like Jekyll and Hyde," she says. "He was really grabby and putting his hands places. He got real comfortable. I think he had just drunk a little too much."

Although DeLorean had seen other patrons transform similarly around her after a few drinks, she found herself much more uneasy with how aggressive Gupton had become so quickly. So she began to withdraw. Their brief relationship, which had prompted them to exchange numbers and add each other as Facebook friends, evaporated almost as soon as it had begun.

Finding himself ignored, Gupton began to look elsewhere for someone to engage. DeLorean remembers sitting across from the U-shaped bar and watching Gupton walk up to White before she left for the night, thinking nothing of it.

Stephen White, the victim, in his military days; footage from Chemistry showing Gupton and White leaving the bar after meeting for the first time

"Hey man," a hotel worker cried through a phone to a 911

operator while fire alarms blared in the background, "I need police here." The time was 4:32 a.m., almost two hours after Stephen White and Garry Gupton had left Chemistry.

As the hotel employee was on the phone, a shirtless Gupton made his way outside to the parking lot after knocking over a computer in the lobby and screaming erratically. He was, as a Greensboro Police Department spokesperson would later say, acting "incredibly irrationally."

A few minutes later, the same hotel worker would call 911 back to report that there was a fire upstairs and that police had arrived on the scene. When firefighters finally entered the building and knocked down the hotel door on the fourth floor, they discovered the burning body of Stephen White.

The evidence suggests that at some point Gupton began

attacking White with a lamp, a television, and other small pieces of furniture in the room. A used condom was also found on the scene. White lost consciousness during the attack, at which point Gupton set the carpet on fire. Gupton stayed in the room for some time as the fire blazed, later requiring treatment for smoke inhalation, then left half-clothed.

White was ushered to the hospital, where he had both of his arms partially amputated. Teal arrived shortly after, along with members of White's family. Teal remembers it all as a blur.

For almost a week, White fought for his life, but the injuries he had sustained proved too much. Six days after being admitted, he died. Gupton faces life in prison or the death penalty if convicted. Guilford County assistant district attorney Howard Newman declined to comment on the case, but confirmed that Gupton has indeed been indicted and charged.

The day after Stephen White died, Stephen Snyder, a friend of White's from the bar scene, founded the group Justice for All -- The Stephen White Movement, with his friend Megan Hardy. Their goal: to change the hate crime laws of North Carolina to include sexual orientation.

Only 15 states and the District of Columbia have laws that cover hate crimes based on sexual orientation and gender identity. Another 15 have laws that cover only sexual orientation, 14 have laws that cover neither of those categories, and five have no hate crime laws at all. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Act of 2009 does cover sexual orientation in every state, but only on a federal level, applying to crimes affecting "interstate or foreign commerce" or in federal territories.

"[Gupton] chose to go with a gay man who he knew was gay and have consensual sex," Snyder says. "Maybe he never planned that, but that's what he told Stephen to get him there, and then he took Stephen's life because he was gay."

An alternative theory is that White was killed not because he was gay, but because Gupton was gay. And couldn't deal with it.

Snyder is among many in the Greensboro LGBT community, including Alex Teal, whose first reaction on hearing of White's murder was to label it a hate crime motivated by the assailant's fear of his own desires. There is no evidence that Gupton went out that November night with the intention of killing a gay man. Instead, it appears that he went out to his first gay bar alone and was confronted with something he wasn't yet ready to cope with.

"My fear is that because we are in the South and there is so much anger about [the legalization of same-sex] marriage, there is even more passion to hate gay people now," says Snyder. "I am afraid that if they go to trial, he will [somehow] get off."

On December 10, Snyder arrived at the courthouse for Gupton's court appearance and was greeted by the Greensboro Police Department, who told him they would be there to protect White's supporters from any backlash. The night before, he had received a phone call from a local church pastor, who told him that all queers deserve what happened to White and that church members planned to be present at the rally too.

The church never showed up. And neither did many of those who supported the cause: Only about 20 people of the expected 92 arrived. Of those, only a few identified as LGBT. For Snyder, it was indicative of the fear that paralyzes Greensboro's small LGBT community. "People are saying that this is what happens when you [legalize same-sex marriage]," he says.

Most LGBT people I interviewed agreed: Outside of gay bars or establishments, they fear showing affection with one another. Snyder, who has had a partner for many years, thinks the striking down of the ban on same-sex marriage has only aggravated hostility toward LGBT people.

In 2014, six gay men were murdered in circumstances similar to those in which White found himself, according to the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs, which refers to these homicides as hookup-related. That may seem like a small number on the surface, but as with other forms of violence, stigma may lead to underreporting.

"We often find with these homicides that law enforcement are very quick to say they are not looking at them as hate crimes, and we sometimes think this is problematic [when] they're very quickly dismissed from an investigation," says Chai Jindasurat, co-director of community organizing and public advocacy at NCAVP. Of the six reported cases from 2014, only one -- the murder of Dionte Greene -- is being investigated as a potential hate crime. Greene was shot in the face while going to meet "trade," or a man on the down low, in Kansas City, Mo. That investigation was mostly due to the efforts of Greene's mother and the Kansas City Anti-Violence Project to get the media to pay attention.

Since White's death, Teal has been slowly purging his partner's possessions as he prepares to sell the home the two men shared. Alone now, he looks west for the future, and plans to move to California once he finishes his graduate work. Kept on the sidelines by White's family, he is not even sure what, if anything, he will be left with to remind him of the life he and White shared.

"I don't know what's going on with his estate because [his family] doesn't tell me anything," Teal says. He recalls a letter that White once received from his sister, in which she blamed his problems on being gay. "And she told him he needs to get rid of me because I am the devil, because I am gay and there is no hope for me."

Teal laughed that letter off the first time, but recently it has come back to haunt him. After being shunned at the hospital, he found himself included in White's obituary almost as an afterthought, relegated from partner to a "friend." Nor was he included in any of the funeral arrangements.

"I didn't know about the ceremony," he says. "I didn't know when to show up until the day of the funeral." During the service, White's military flag was presented to his mother.

"Basically that meant I was shit," says Teal.

He sees nothing left for him in Greensboro. "I am black, Catholic, and gay," he says. "And I live in the South. I feel more comfortable in a straight bar."