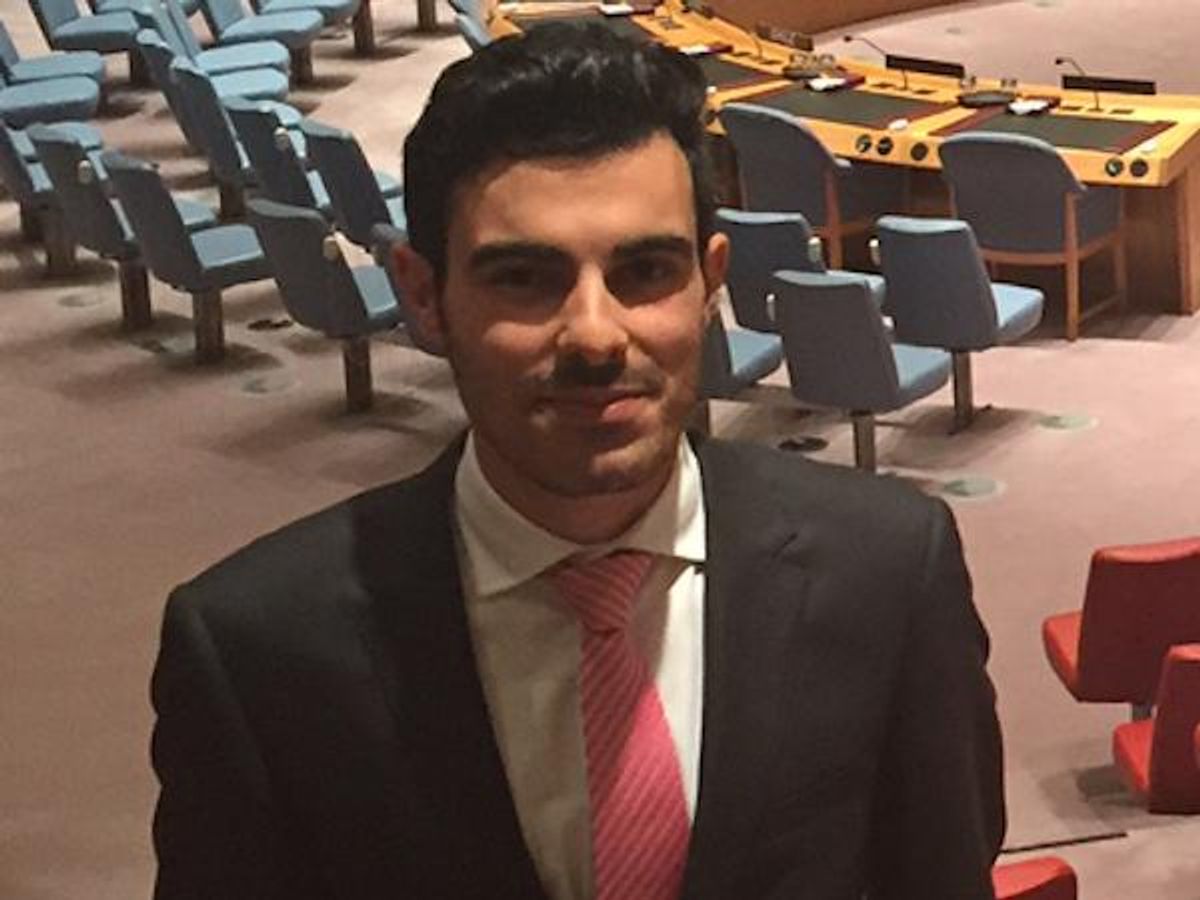

On August 24, Subhi Nahas made history, testifying before the United Nations Security Council's first summit on violence perpetrated against LGBT people by the so-called Islamic State (ISIS). A Systems Administrator and Designer for the Organization for Refuge, Asylum, and Migration (ORAM), Nahas has lived in San Francsico for four months, a situation made possible after he was granted refugee status by the United States government.

Since the Syrian conflict began in 2011, half of the country's population has been displaced, many internally. As ISIS has grown in strength and territory, however, more and more are fleeing the country, with hundreds of thousands now risking the perilous journey to Europe. While Nahas was not a part of the wave of refugees Europe is currently struggling--or, in some cases, resisting--to accomodate, he nonetheless remains a part of the wider Syrian exodus, one of the many millions who have been forced to leave their homes in the hope of finding safety.

From the city of Idlib in northern Syria, Nahas was the firstborn son in his family, a position that carries with it heavy societal expectations. He was different however, in a way that he wasn't able to understand or articulate until he met with a psychologist at the age of 15--a man who would betray his young trust, inform his family, and recommend strict measures to curb his sexuality. Life for gay men in Syria has become unendurable with the rise of ISIS, but as Nahas attests to, things were bad long before the self-proclaimed Islamic caliphate took power.

Out: What was it like for gay people before the Arab Spring revolution in 2011?

Subhi Nahas: There was never a true gay community, not even in Damascus. There was a very small group, and it was always under attack from the Secret Police. They would try to make you feel comfortable, feel like you had a safe place, and then they would raid those places, arrest people and imprison them. Homosexuality is criminalized in the penal code and punishable by up to three years in prison. Homophobia is deeply ingrained, and society takes it upon themselves to enforce the laws. If you're caught, they blackmail you, extort you, and threaten to tell your family. It's been like that for a long time. Older generations tell of being mistreated, being blocked from services, facilities, medical treatment, just for being gay.

What was your first experience with these attitudes and laws?

The first encounter I had was with regime [President Bashir al-Assad, before the revolution] forces. They were doing a routine sweep at a checkpoint while I was on my way to university, and they took all the young people, including me, out to a detention place. It was this house in the woods, and immediately you could see that there had been people there before, you could see their blood, their stains. It was really scary.

They noticed that I'm a little bit different in the way that I walk and talk, and they started to call me names. They asked me questions, about my family, about why I spoke the way I did. They started to say things that I'd rather not repeat. They released the others, but they kept me for at least 30 minutes more, and I really thought that they would rape and kill me, I had no idea what would happen. But then they just released me. I don't know why, but they did.

What happened after that?

After that, I couldn't risk going back to university, so I stayed home, and that meant things escalated with my family. Especially because, a few months later, Islamists came and things really deteriorated. My father stayed home then a lot too, which meant he was seeing me more. He didn't like what he saw, and things got violent.

How did things change when Islamist groups took control after the revolution?

What happened was, an Islamist group, an al-Qaeda branch, took over the city of Idlib. And as they gained more power, they started to enforce Sharia law. They started to put checkpoints, and they started to target anyone who was different. One day, they arrested someone I knew and accused him of being homosexual, I think because of something they found on his phone. After that, they went into the mosques and announced that they would cleanse the city of anyone involved in sodomy, which took the insecurity to a whole new level. Now, even if you looked a little bit different, wore jeans that were a little bit tight, they would target you and interrogate you for five or six hours. And even if they believed that you weren't, after being released you had to follow their strict rules for acting and dressing.

When did you realize you had to leave Syria?

Within two or three months of the Islamists taking control, I left Syria. I called some of my friends in Lebanon, explained the whole situation, and they were generous enough to welcome me to their houses. I arranged a taxi, and told the driver that he had to take care of all the procedures at the borders and checkpoints, because if I spoke, if I had any interaction with these people, they might have noticed how I am and not let me leave. It was a lot of work, a lot of planning, but it worked, and I'm very thankful for that.

What happened after you got to Lebanon?

There were not a lot of job opportunities, so I was very underemployed. After six months, I was able to get a job in Turkey for a magazine I was working for remotely. So I moved to Turkey, secured a senior position at a non-profit, Save the Children, and ended up staying there for about two years.

Why did you leave Turkey?

I was living in a city close to the Syrian border, and as ISIS gained more power and took more land, things became more dangerous. A friend of mine told me that someone we had known in high school had joined ISIS and said he wanted to kill me because I was gay, and because I was also working with an LGBT NGO in Turkey, and working on an Arabic gay magazine. And where I lived, there were ISIS operatives roaming free--it was an open border, and they passed through easily. If you were Syrian, you were never safe, they always knew who you were and what you were doing. So for a time, I was moving from safe house to safe house, until I finally ended up in Istanbul and registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR].

What has changed since ISIS took control?

Well, thankfully, I was not there to witness ISIS. But all they've done is publicize what everyone else was doing before. The killing of gays were not as brutal, but they were still happening. The Free Syrian Army, Jabhat al Nusra, I personally know at least two people they killed, but they never talked about it. They didn't want that spotlight. But ISIS does. They say that they are protecting the community from these "perverts," from people who will destroy society's morality. They can't offer water or services, but they can offer that. And it seems like it's working. We've seen from videos that if a gay person doesn't die from the fall off a building, the people watching stone him to death. ISIS is being this brutal, this public, to gain support.

What was the process of applying for refugee status like?

First, UNHCR processed my case, interviewed me, and accepted me. Then they went about looking for a country to accept me. So there were more interviews to build up my case. I was told that the United States had accepted my case, and then they set up an interview with an American legal team. Then I was referred to Homeland Security, who then sent a representative to do another interview to see if I met US standards. And I did. It all took about 12 months, and then I moved to San Francisco--I had a job set up already.

What was it like speaking in front of the United Nations Security Council?

It came about because I work with ORAM [Organization for Refuge, Asylum, and Migration], and the CEO got a message asking for recommendations for people willing to speak about their experience at this UN meeting on LGBT abuses around the world. It was going to be the first time that a voice from Asia or the Middle East was heard like that, and I wanted to be a part of it.

There were a lot of countries and organizations there, even two representatives from Syria. And the countries that spoke, they were very positive. Which was so weird. I was expecting hostility. Russia and China, for example, they were there, but they refused to speak, but of those that did speak, everyone wanted to do something, everyone wanted change. It's a small step, but one that we needed.

How typical do you think your story is?

I think my story is typical, what I went through, but many others have had to endure far worse horrors, far more hardships trying to escape. I consider myself very lucky that I had all this help, and that's what I'm trying to establish with my work: a system that allows people to get help faster, that will protect them where they are now--Syria, Lebanon, Turkey--and help them when they finally arrive in places like America. We need a system to protect these people when they are able to get out.

Cooper Koch and twin bro spark controversy with eye-popping 'White Lotus' parody