Ron Vawter,an old college friend, stood in front of me on the corner of Waverly and Sixth Avenue. He seemed to glide sideways, somehow catching me unaware, and kissed me on the cheek. We hugged each other for a long time. When I finally looked at him at arm's length, Ron seemed etched out of the crisp autumn afternoon. He had often created a strange clamor within me. So much of his work as an actor with the Wooster Group was a kind of subversion: a way to get at the truth of things. I both loved and was terrified by this part of Ron. His cadence and stride immediately captured me, and he called me by a name that no one else ever did. In his most soothing voice he said, "Jimmyboy."

It was the last week in March of 1988, and we hadn't seen each other for some time. We shrugged and walked together on this short, whimsical street toward the red brick of the Northern Dispensary. We turned left onto Christopher at the end of the block near Sheridan Square. Ron's life as a performer had begun to take off in so many ways, and I had been busy with Carly. Ron said, "Let's have a drink at Boots and Saddles, a gay leather bar on Christopher Street. There's a cute bartender who's a friend of mine."

"You know I don't drink anymore."

"Right. Do you mind if I do?"

"No, not at all. Let's go."

Ron ordered a Jack on the rocks and lit a cigarette. He loved to smoke, and we had smoked and been drunk together so often. I wished I could have joined him for a few, but I knew I couldn't.

"Jimmyboy, Carly Simon?"

"I know, it's odd, isn't it?"

"I guess. You'll tell me all about it -- everything."

"What's happening with you?"

"Well, my commercial career is finally taking off. I've made some films recently -- small but good roles."

"That's wonderful."

"It's quite bittersweet."

"Why?"

"I have just been diagnosed with the AIDS virus."

"Oh, Ronnie."

We hugged each other in the dim light of Boots and Saddles. The cute bartender looked on approvingly. I kept touching Ron, and we just kept moving closer and closer to each other. I wanted to kiss Ron down to his bones and tell him with one physical gesture how much I loved him. We were alone here for most of the afternoon. Just the two of us trying to share what had happened in our lives. We wanted to be alone just to feel and taste and see each word and gesture.

--

We rushedthrough so many people and memories -- all the nights at various gay bars and all the guys I had slept with before Alannah and I were married, many of whom Ron helped me pick up. I especially remembered a couple of nights at a gay bar in Brooklyn and a flirtation with a sexy young man named Noodles. We danced through the night in a haze of booze, pot, and amyl nitrate. Every time I took a hit of amyl nitrate, I moved closer toward him. Noodles was dressed in skintight white bell bottoms, and his legs were muscular, lithe, and sleek. As the drug took over, I so wanted him, and when the short effect of the drug wore off, I wanted him so much less. This sensual push and pull went on all night, and I felt that sleeping with Noodles would have forced me to declare something forever. I was always drunk or high on something in those days in the gay world, so nothing felt definitive, but this moment was different, as if Noodles could overturn everything within me. Something about his total commitment to his sexuality would have meant that I would have to commit also, and I knew I couldn't, just couldn't. Yet the image of Noodles's swerving body and wide smile stayed with me forever.

I would see Ron again fairly soon. Happily, he was an acquaintance of the writer Edna O'Brien, who had become a great friend to Carly. Edna had written a play about Maud Gonne and William Butler Yeats, and we thought Ron might be of help.

Edna had a sharp and trained eye, and she recognized Ron as the real deal, a true artist, and admired his work. The last production I saw of Ron's was a one man tour de force called Roy Cohn/Jack Smith: one of the most terrifying and moving theatrical pieces I had ever seen. Ron played two men who had died of AIDS while Ron himself was dying

of AIDS.

I knew Ron and Carly would like each other; they were both zany sorts of artists, and that quality was intertwined in their work and personalities. I worried that Ron in a mischievous mood might reveal some of my gay secrets to Carly, but I was willing to risk it. I was never exactly comfortable when the two of them were together. I presumed that somehow the truth would come out, but it never did. We all got busy with other things, and then Ron got sick.

I sat one afternoon with Edna, Ron, and Carly at a restaurant in SoHo. As I looked at the three of them, I felt excluded. These three had already achieved a great deal of success as artists. I knew I was just like them; I just hadn't yet put myself to the test. There was something in the three of them that I lacked: a kind of bold and vigorous assertion of self. I felt they all cared for me deeply, and yet I lacked what I felt they had assembled -- an array of tricks. My alcoholism had interrupted me. Yet in other ways, I felt more mature than all of them. I thought they were all capable of harming themselves and others in a way that I never could: They lived much more in the sway of their emotions. I felt sounder, as though nothing would ever overturn me.

I was struck by how much Edna and Ron knew about me in certain ways that Carly never would. Edna knew all about my being an Irish Catholic from a poor and violent background, and Ron knew the other stuff. These were two parts of me that Carly would never really know, and they were at the core of what I had wrapped in a kind of secrecy to protect myself.

My calls to a sex line ominously named "The Dungeon" would indicate yet another circuitous path. It was a gay S&M telephone line that appeared in ads in The Village Voice. We had set up a writing office for me in a room that Carly had on the roof at 135 Central Park West. It was a remarkable space -- soaring above the park in a pyramid-like structure that had tiny, high windows. Sometimes when I would get bored, I would call the S&M sex line and chat with guys about what they wanted to do to me. They all seemed to have growling bass voices with very particular and bizarre instructions:

"You are a worthless worm. You will be my slave."

"I will?"

"Who gave it permission to speak?"

"No one. That's right."

"It will only speak when I tell it to."

"OK."

"That is not how you address your Master. You will start every sentence with Thank You, sir."

"I will? Oh, thank you, sir."

I never remember being sexually excited by any of it. I was just fascinated that people had such unusual desires and were willing to express them to others so candidly. We had so many phone lines that it never dawned on me that someone in Carly's accountant's office would be checking the bill and report back to her that calls were being placed to The Dungeon.

Carly lived with suspicion. She had been trained in a house of lies as a child, and her many relationships with celebrities, artists, alcoholics, and drug addicts had sharpened her sense that she was never getting the truth. I knew that she would trace the calls to their source, so the only thing for me to do was to admit what I had done. I was terribly ashamed on so many levels, and I made an immediate appeal in my confession.

"Please, whatever you do -- don't make me talk about this ever again. It will never happen again, I promise you, and please let's not discuss it. It's too embarrassing."

I sobbed throughout this admission, certain that this would be the end of our brief marriage. I am not sure whether Carly actually understood that it was a gay S&M line. After a day of thinking about it, she said she would never mention it again, and in fact she never did. The last thing she said was, "I think it must have something to do with the seminary. You must be a very bad boy. Do you think you need to be punished?"

We didn't revisit the subject again.

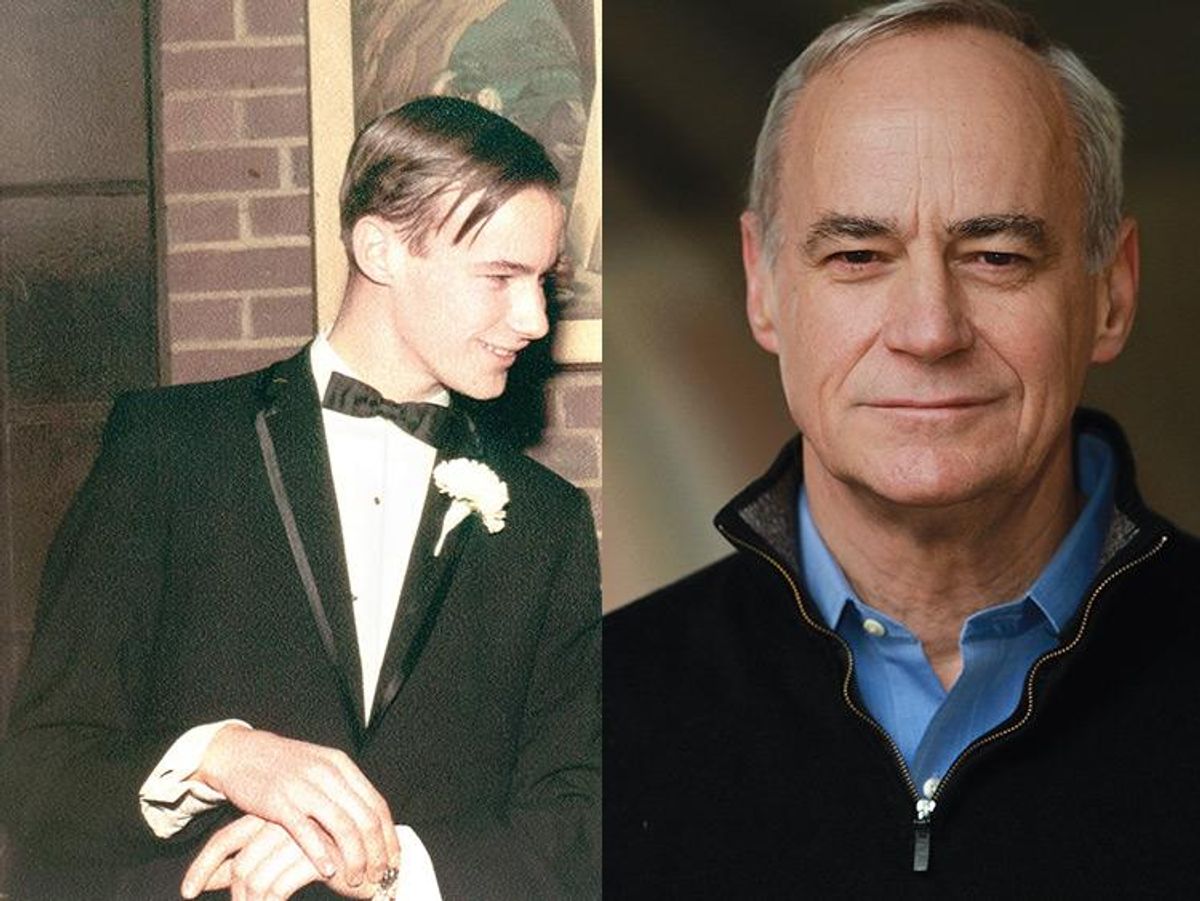

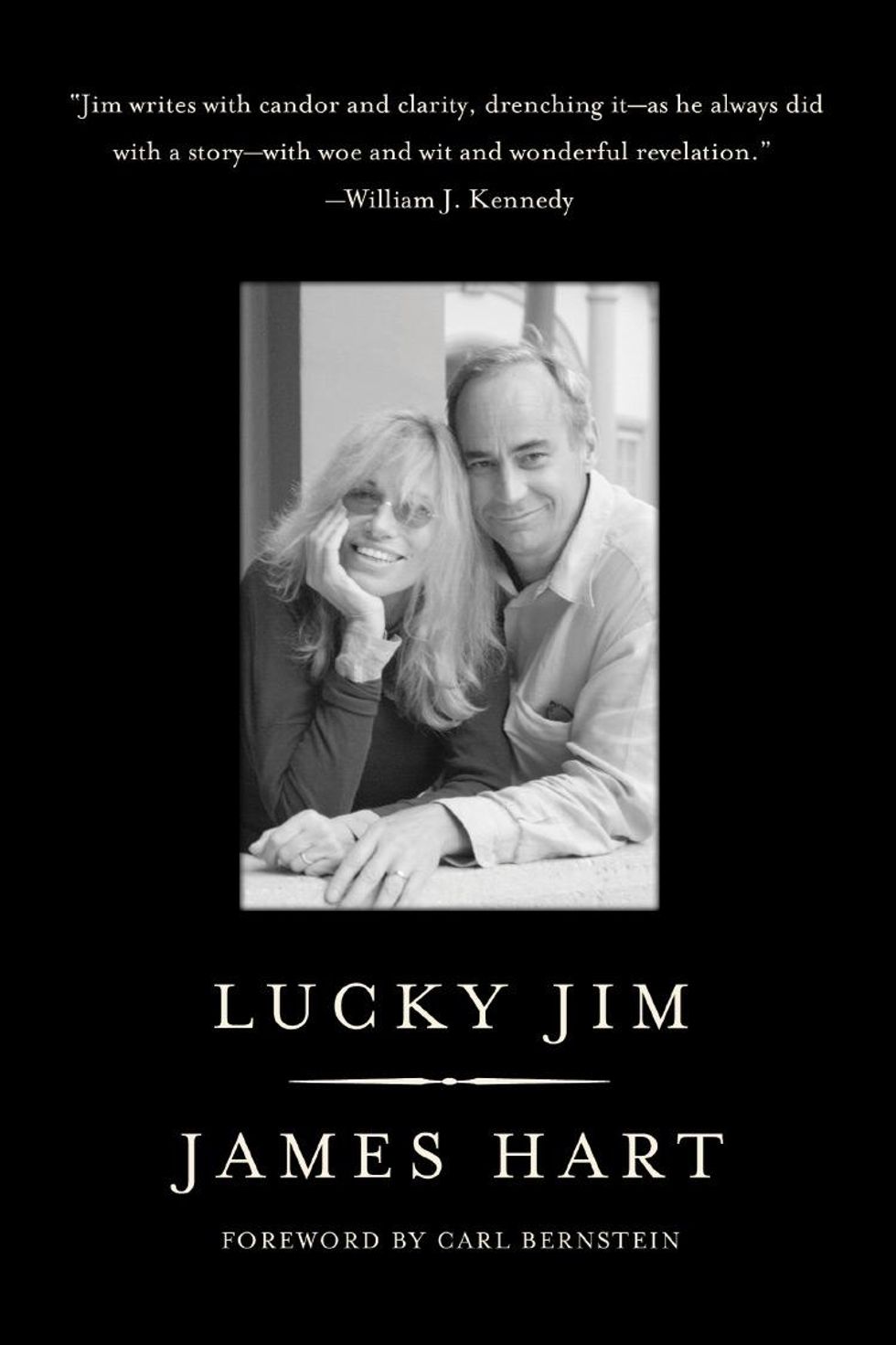

This edited extract is taken from Hart's memoir, Lucky Jim, now available from Cleis Press. Click here to purchase.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.