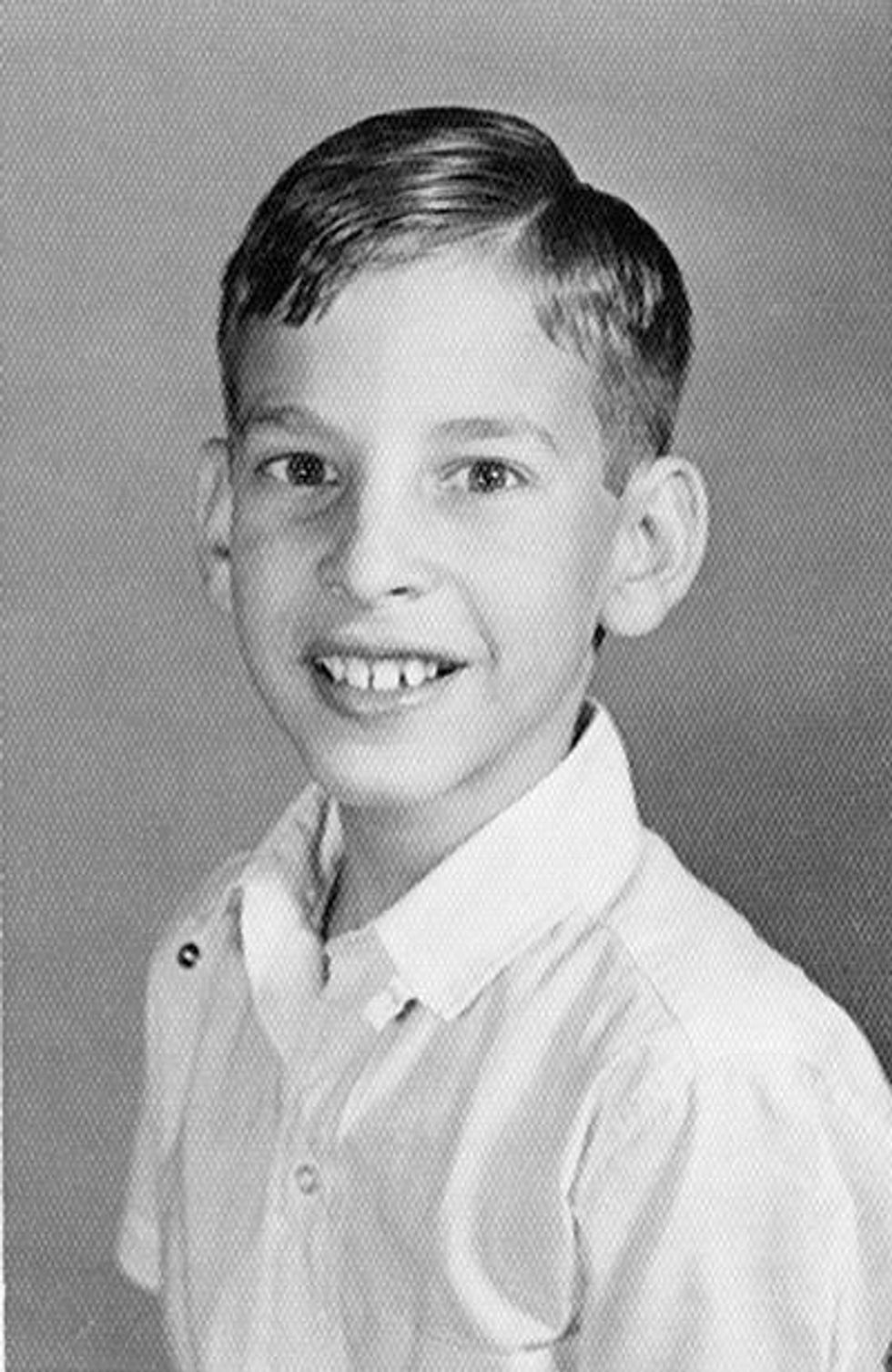

As a child,my best friend was Robby Anton. We thought the funniest thing was to telephone some hotel in the red-light district and attempt, in elevated language, to make a reservation. Or else we'd sit in his mother's Cadillac and be a couple of stars driving from Fort Worth to New York to open in a Broadway show. While others played ball outside, Robby and I would lie around his house or mine listening to Sophie Tucker, last of the red-hot mamas, sing: "Who wants 'em tall, dark, and handsome! Who cares about glamorous guys!" We loved the great indoors. One Saturday, in a corner of my bedroom, we opened an expensive Polynesian restaurant. Ordinary boys we were not. We adored theater and ceremony and pomp and pretense of every kind. We especially loved funerals. One time we put on a funeral for a bookmark.

There has been life for me after Robby, more than 30 years of it, but there was none before. His parents were the closest friends of mine, and so it happened quite naturally that Robby, three years older than I, became my first friend, a piece of luck I'll marvel at till I die: to have been granted from earliest childhood the company of a creative genius.

My earliest memory of him must be from when I was about 5 and he 8--an 8-year-old artist in the spell of his calling, which was puppetry. He had a stage his parents had brought back from FAO Schwarz (I wailed till my parents got me one like it), complete with a set of hand puppets: an alligator, a glowworm, a cockatoo, a bearded lady, a heavy-lidded ostrich, a monkey with a scarlet maw, and so forth. And how, with his effortless theatricality, Robby stirred them all to life! After a few attempts to emulate him at home on my own bare stage, I folded it up and put it away. Under my tutelage the puppets had refused to live. With glass eyes they reproached me.

Anything on a stage was rapture. Galvanized by Fort Worth Opera's Madame Butterfly, we decided to mount a version of our own and commandeered two girls from Mrs. Westbrook's class, Libby Lee and Angela Tipton, to play Cho-Cho-San and Suzuki. I myself would take the role of Captain Pinkerton. Libby and Angela were a couple of troupers. They had ballet recitals to their credit and we felt, somehow, that their tutus and tights would look Japanese enough. I'd wear my new seersucker for Pinkerton's regalia. At Record Town we bought the Angel LP set of Victoria de los Angeles and Jussi Bjorling singing Butterfly. The idea was that Angela, Libby and I would lip-synch the whole thing. Robby painted the flats and put me in charge of staging.

Angela, a fiery girl, felt miscast as Suzuki and hankered for the starring role. Midway through the dress rehearsal, that hellcat spat on us both. Robby said, "You're gonna get it, girlie!" Libby leapt in. I gave her a hard pinch. Still in their tights and tutus, she and Angela flew out the front door, roller bags clattering behind them. Libby's had a dud wheel, which for some reason made Robby and me laugh uncontrollably.

"Did you see that wheel?" he managed to say through tears.

"She deserves it!" We fell against each other.

Last we saw, Libby and Angela were waving down some car. Of a nice person, we hoped. More helpless laughter. But our Butterfly had perished in the larval stage.

Many years later Robby said: "Pathetic of us to have employed those girls when what we wanted was to be Cho-Cho-San and Suzuki ourselves."

It was with puppets that Robby began and with puppets that he ended. That he became in the last decade of his brief life one of the greatest puppeteers who has ever lived is not doubted by those who saw his work of the late '70s and early '80s. This time he made the protean characters from scratch, a cast of tiny finger puppets who broached the darkness, made alchemical discoveries, suffered and were metamorphosed from their illusions. His theater was a single-handed mythology, outside all creeds and yet systematic. William Blake comes to mind as a comparably uncompromising artist, and Blake was among Robby's fascinations.

Like the author of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Robby invented an allegory in which characters embody instincts and faculties. He drew the numinous circle around these human things in order to show, as myth does, how interfused they are with a universe of powers transcending them.

In other words, he had the religious gift (so lacking in rationalistic me). Our journey out of the little world of reason and sense experience and into eternity was Robby's mature subject. Our alleged mortality he saw as a deceit.

Everything the Romantics taught about the momentousness of childhood, about original untutored prowess as the source of art, was borne out in Robby. What happened is what always happens: Maturity intensified by orders of magnitude the early promptings and intuitions. The cabinet of curiosities from FAO Schwarz gave way to a visionary company of the puppeteer's own making.

They delighted the eye and filled the mind, Robby's homemade creatures, who would turn to the deity who'd made them with love, fear, bafflement, the whole range of feeling. His parents must have wondered what they'd wrought in this prodigal son. But along with bewilderment there was love, there was money. The hothouse flower was encouraged to bloom. He had pictures to look at, plays and musicals and movies and operas to go to, books to read, records to listen to: the art of Durer, Blake, Fuseli, Redon, and Grosz; the films of Fellini (especially Juliet of the Spirits and Toby Dammit) and Kubrick (especially 2001); the writings of Paracelsus, Saint John of the Cross, Jakob Boehme, Meher Baba, and C.G. Jung; the songs of Brecht and Weill (especially from Mahagonny) and of Cole Porter (especially from Kiss Me, Kate). The American musical theater was Robby's Great Code.

Robby's puppets lie orphaned in a trunk and will never be famous. But fame and the sublime are only accidentally related. This we must believe, or else surrender to a worldliness honoring only success. Robby's immense gifts were known to but a handful of people and it may be, given his indifference to recognition, that he'd have remained a close-held secret even if allowed to live out a long life. Once in a while, however, I still meet someone who actually saw a performance of his. It happens less and less, of course, and eventually the next-to-last and last of us who saw the thing will die. For now, though, we are a happy few, content to have sat in the long ago before a tiny stage beholding a stupendous wonder of art.

The long ago: that is to say the sunlit late '70s. Then a cloud settled down on Earth to see how many of us it could devour--the part of the story everyone knows. Robby was an early case. He fell ill in the spring of 1983. Watching my adored friend as the darkness enveloped him, I did not imagine how many more I'd see vanish in their turn.

That subtraction of wit, grace, brains, and beauty from our midst is unbearable to contemplate. How is it we did not, in compassionate horror, pull the earth up over us? How is it we who were spared have gone on creating, laughing, renewing ourselves with love? Is the appetite for life simply too great, greater than our accumulated griefs? And what, for their part, do the lost travelers under the hill think of us? Do they applaud our resilience? When I get a moment with them in dreams they tend to say that yes, they do.

George Richmond writes to Samuel Palmer, Blake's disciple: "Just before he died His Countenance became fair. His eyes Brighten'd and he burst out into Singing of the things he saw in Heaven." Justice would have Robby full of years and singing. But Robert Anton died young and alone and humiliated and frightened--and by his own hand, having endured enough--in a Los Angeles hotel room.

This is an edited excerpt from The Hue and Cry at Our House: A Year Remembered by Benjamin Taylor, available now through Penguin Books. Copyright (c) 2017 by Benjamin Taylor.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right