News & Opinion

Please Don’t Google Trans People’s “Before” Photos

Please Don’t Google Trans People’s “Before” Photos

Author Thomas Page McBee gives us three reasons.

December 21 2018 5:02 AM EST

November 04 2024 10:02 AM EST

ThomasPageMcBee

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Please Don’t Google Trans People’s “Before” Photos

Author Thomas Page McBee gives us three reasons.

A few months after I began my medical transition, my mom was still alive, and as we planned my trip home for Christmas this year she asked -- with great sensitivity and trepidation -- what to do about the photos of me that hung on her walls and her refrigerator. She intuited, rightly, that these "before" photos of my high school graduation, family Christmases, and childhood trips to Mexico, might cause me pain, and she was right. Would I like her to take them down?

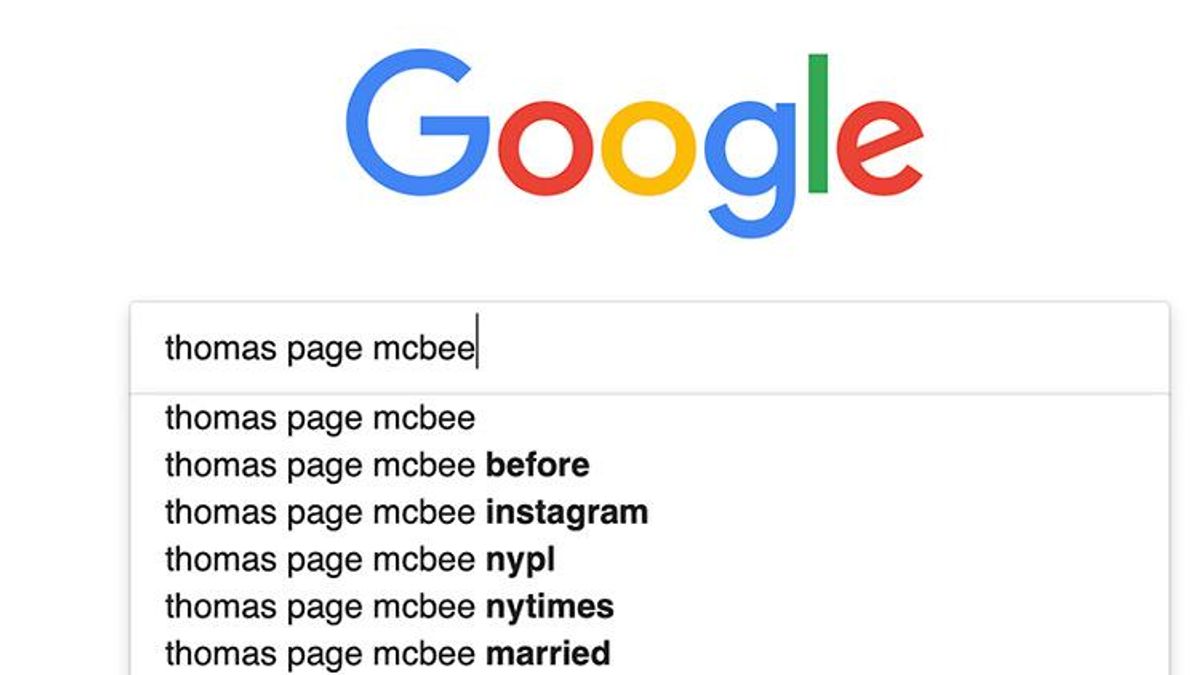

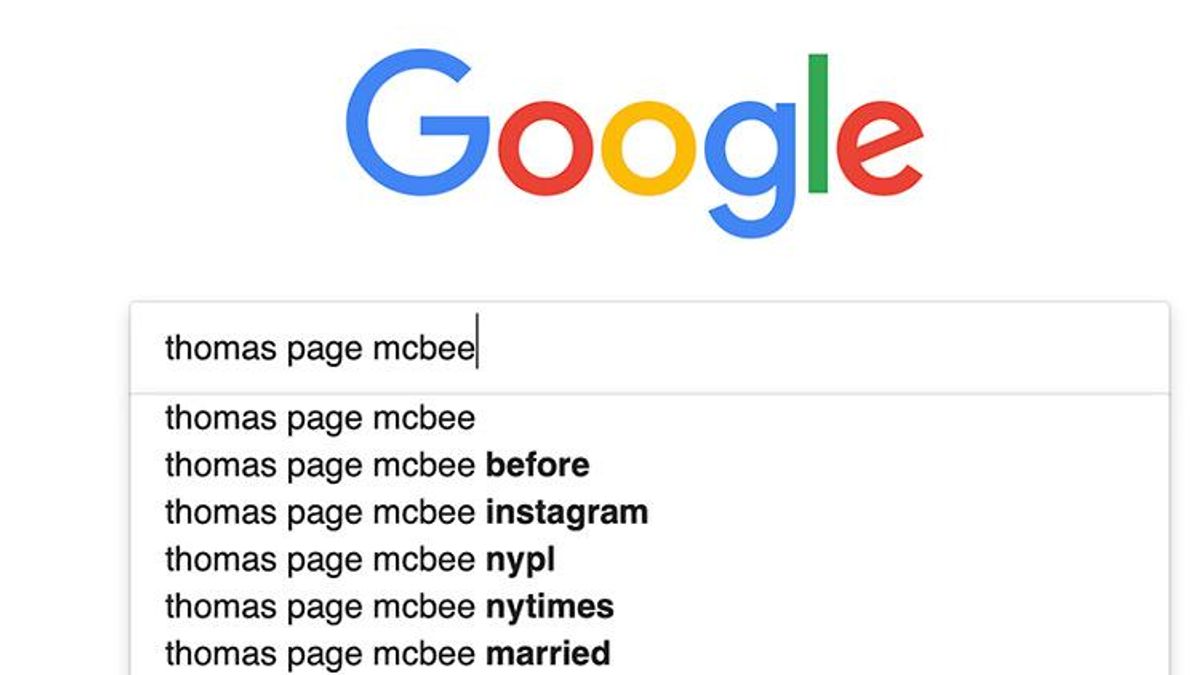

I thought of my mother the other day, when I ran my name through Google, looking for an article I'd been featured in recently. This, of course, wasn't the first time I searched my name, but doing so was a dark reminder of how others haven't been so considerate. I've written about gender and my life many times in the seven years since I transitioned, and have always been disappointed and angered to find that a top search for my name involves the word "before."

So, what's the problem? Let me explain.

For some trans people, images from our pasts bring up painful memories.

Though there is a whole genre of trans folks who have willingly chronicled their transitions on YouTube and other social media platforms, and though I am grateful to the trans men who felt comfortable doing so, because they gave me a sense of how testosterone might impact my body, I have never once been interested in doing the same. It took me a long time to even look at photos of myself "before," because it felt so painful to be reminded of the unhappiness I'd felt with my image, the creeping dysphoria that ultimately set me so on edge. I gave up everything and began my life again at 30 in order to show the world who I really was in that mirror. They remind me of the reasons why I waited: The fears I'd twinned with being myself. I was afraid of being cast out, of dying alone, of what hormones might do to my lifespan, and my health. I was afraid, also, of being a man in the world, because--as a survivor of both childhood sexual abuse and a violent crime in which I almost died--I was afraid of men. So I carried on in a body that felt like it wasn't wholly mine. To look at those images has been a journey of grief for me, one that I've only recently come to some kind of terms with, and to integrate into my holistic sense of self. I am a public person, and I've never shied away from being honest about my experience in a way I hope is helpful to people of all gender identities. But the relationship I have with my own image is for me, and me alone.

So, frustrated, I posted a screenshot of this Google search on my Twitter and Instagram, and told people that this impulse wasn't acceptable: "Don't do this." The responses varied. Many trans people screenshot their own search results in commiseration. Lots of people responded with some variation of "ugh" or "yuck." A few trans folks pointed out that they too had searched the internet for images of trans people "before" in order to orient themselves before starting hormone therapy. And several cis people, to varying degrees of belligerence, took issue with my concern and "debated" me.

Making "passing" a reward is harmful, and sets up a false binary.

Trans bodies in media are often framed in this neat narrative of "before" and "after," a practice that some trans people themselves do in celebration, which is a personal choice I respect and honor. But the practice itself first appeared in American women's magazines in the 1950s, a time when women were expected to embrace a highly gendered "beauty makeover" narrative of transformation following the independence many of them had during World War II, when women worked outside the home as part of the war effort, taking the jobs of the men who were off fighting in order to keep the country's economic engine running. After the men returned home, the US entered a period of intense gender traditionalism, designed to reaffirm patriarchy and encourage the once-independent women to confine their aspirations once again toward the domestic. Women were to focus their efforts once again on their appearance, a highly successful form of social control exemplified in "beach body" success stories, for instance, that persist today.

Susan Stryker posits in her essential text Transgender History that trans model, actor, and ex-GI Christine Jorgensen was "the most-written about topic in 1953." Jorgensen, Stryker says, "could present herself in public as young, pretty, gracious, and dignified" -- in other words, the first trans celebrity was one who conformed to the (white) beauty standards of the day and, ironically, helped assuage gender anxiety after the war.

Jorgensen's celebrity also exemplifies the ubiquity of gender anxieties during the postwar era, a tumultuous moment for the gender binary at large. In fact, a trans person's ability to "pass" was -- until recently -- the determining factor for doctors deciding whether or not to prescribe hormones or surgery. Gatekeepers historically required trans people to live for a trial period in their "chosen" gender before even considering medical intervention, setting up trans women especially for violence and discrimination. We learned, through our elders, what narrative to use to get access to medication for our dysphoria, which included the now-ubiquitous "born in the wrong body" story. Though that story certainly holds truth for some people, I personally delayed my transition for years because that framing never made any sense to me. It felt borne of shame, as if my body were the problem, and not the world's general lack of imagination about trans bodies, which have existed throughout time and space.

There is no "before" and "after."

Most meaningfully, the narrative of "before and after" invalidates my trans and gender nonconforming siblings that don't "pass" as cis. Many of us don't take hormones for all sorts of reasons. Many of us don't pass for all sorts of reasons. For there to be a "before," the presumption is that a visible "after" is the goal. While I don't fault trans people searching for models, as I once did, I do wonder about, for instance, the cis people who responded to my post to social media admitting (sometimes defensively) to having performed this exact same search.

Some, like a parent I spoke to after posting about this on social, said they were looking for ways to "explain" what being trans meant to their child. She and I had a productive exchange about how to use trans folks' own words to tell the story of who we are. I let her know that I've never had a problem explaining being trans to a child -- children accept trans bodies easily, because they have never been taught to see us as alien to the human experience in the first place. Others admitted curiosity but claimed that they were merely trying to "understand" what it was like to be trans. I suggested to them that to "understand" being trans would literally require being trans, so a better use of time and empathy might just be to connect to the universal elements of our human experience: We all know what it's like to "transition" identities, and most of us don't do side-by-side comparisons of our lives before and after, say, a divorce or birth of a child or career change in service of making our experience palatable for the invisible masses.

There were the (many) people who protested that my status as a "public" trans person required me to accept the curiosity of others about all aspects of myself, even that which I choose to keep private. These were the most difficult folks to engage with and, I suspect, the bulk of the ones doing the searching. For them I offered a genuine invitation to reflect: If empathy is truly your goal, what would it be like to read my work, and to sit with the discomfort of not-knowing what it will ever be like to be me, without rooting through my past in an attempt to "make sense" of it all? What if, crucially, I've offered all I can of myself, and I'm already making sense? The person you see, the "after," is all there is to it. I'm not who I "became," any more than you are. I am who I was always becoming.

My mom understood that, the day she asked about the photos of me, her first-born, scattered proudly around her house. I thanked her, and asked her to please take them down. That was our last Christmas together. When she died suddenly nine months later and my siblings and I cleaned out her house, I found the images she'd tucked away in closets and drawers and felt a sharp pang of guilt at the thought of her, honoring my becoming by letting go of her desire to see my face every day, to cherish her memory of it. How lucky I was, to have a mother willing to see me as I am, regardless of who I'd been. In her honor, I'm asking the same of you.

RELATED | Masterpiece Cakeshop Now Being Sued for Transphobia