The dermatologist casually called my skin "angry." He had said that, at this point, permanent facial scarring was inevitable. One night in late fall during break my senior year of college, when my face was especially red, I looked up on the Internet: "How to burn off acne." There were, to my surprise, some hits.

I needed a butter knife and open flame. I needed to see myself again.

There is a two-year window--20 to 22--during which no photos were taken of me, and if there were any photos taken of me I destroyed them or otherwise urged that they be destroyed.

For most people, acne is a fleeting nuisance, an occasional bother, a pink dot on the neck that appears and vanishes like the kiss of a mosquito. For me, it was a sudden and disfiguring force, a brutal assault on my features that arrived just as I had intended to emerge into a body and life that had some semblance of apparent maturity. My acne was by most accounts moderate until I was prescribed twice-daily doses of doxycycline, at which time my face erupted into severe nodular acne that ran up my jaw, across my forehead, settled in difficult bumps around my nose--the only skin untouched by the aggravated red nodes just under my eyes. Taken off the medication, the acne failed to subside. I looked bad, and I felt worse. For those who have not experienced it, nodular acne feels like marbles under the skin. It keeps you from looking at other people in the eyes.

This almost instant change in my face made me actively look at myself in ways I had not been looking at myself before. Ironically, looking at and physically evaluating myself for the first time also meant trying to erase myself--my acne, and what else I saw undesirable there in the mirror: my voice, my body, my queerness.We talk about hate often, but we don't talk enough about how transferable hate is, how quickly it can spread, like a dot of blood on a napkin. One moment I was disgusted by my skin--I hated it. But unlike topical creams, this hate sank in. It expanded. It corroded. It made me fall in love with trying to erase my face, trying to erase my queerness.

On the outside, I was being disfigured by pustules and red welts that, once faded, instantly reappeared elsewhere. On the inside, more was happening. I was spending nights alternately pouring over online message boards for severe acne. I took any advice too far.

I had been dealing with severe acne through my senior year of college. On the day of the graduation ceremony, waiting in line in those dark blue robes, my skin was a uniform red sunburn that hid some of the acne. My friends were in that long line, drunk already as the sun glared down.

"Group photo!" someone said, and instantly I asked for my friend's camera.

"I'll take it," I said, and instructed them all into a pose as I lifted the camera and disappeared behind the lens. The sun slanting down in a single cutting ray, the gown trapping heat until it buckled around me, sitting on that football field waiting for a diploma. The camera in my hand, the moment before covering my eye, when I could see myself reflected, my face miniature in the lens. Half those friends: Now? I couldn't tell you what they looked like--the photo is on someone else's camera. And I wish, I really do, that I could tell you what I looked like, too.

I had expected the dull knife to glow white with heat as I held it over the flame, but it stayed somewhat disappointingly silver. The rest of the house asleep, I moved as quietly as possible. I imagined justifying whatever this would do to my face to my parents and siblings the next morning--or, the thought occurred, if they would even notice. I still remember the heat of the dull curved blade next to my face as I brought it toward my skin and hesitated. I wondered if it would make a sound. Instead, I put the knife down. It actually hadn't occurred to me until that very moment the degree to which I might feel pain. That was how I had considered my acne--that my skin was so not a part of me that it might, by proxy, endure this pain for me.

An incomplete list of things I used to make face masks:

Baking soda

Honey

Lemon

Avocado

Oatmeal

Apple cider vinegar

Toothpaste

Egg whites

Set aside the fact that I didn't really know what I was doing mixing and applying these ingredients and that these things probably at times even contributed to my acne. Set aside the fact I even knew this at the time. I was desperate. I was willing to take anyone's advice. I ordered expensive creams that smelled like lime and bleach from websites with insecure payment pages. I wasn't acting like myself because as far as I was concerned I was not myself--not until I fixed my skin.

I would leave the viscous mixtures on for hours, usually at night. I would not leave my bed. I would write bad short fiction and take breaks to remove excess mask, or dab it if it got too runny. I was saying to the world: if you aren't going to give me the face I deserve, if you aren't going to give me my face back, I'm not going to show my face.

If I can't appear as I want to, I thought, I'm not going to show it.

"It has to go away," I heard my aunt whisper to my mother one night from my parents' sunroom. Christmas: tree lights, the smell of candles burning. Snow falling outside. And then, after a pause: "It has to go away--doesn't it?"

It occurs to me now that she could have been talking about either thing: my skin or myself.

There will always be someone talking about how I can change. When I was young, I had no control over the people who were around me, and they often assumed a potential for change in me where there was none. Realizing I couldn't change my skin no matter what I tried, when others told me I could, translated subconsciously into a helpful message for my queerness: I can't change this either.

The connection between my acne and my queerness has everything to do with the eventual realization that there are things you cannot change about yourself and that you will come to love these things eventually.

But it is important to see ourselves before these transformations. There is a gulf of difference between being able to tolerate being seen as gay--between "coming out"--and a self-acceptance of this queerness. In some ways coming out can stunt our growth toward self-love--it can let those around us assume we are at home with ourselves when we have miles to go before we get there, and we can tell ourselves the compounding lie that it is our fault for not feeling at home in a world that often seeks not to offer us one.

When I stayed up late--until everyone else in proximity was asleep, until I could use the shared dorm bathroom and that mirror to peel off the paper-like scabs that had formed over my face--I was trying to get to what was underneath. But what was I expecting? What was underneath?

It was the most desperate wish.

Anything else.

It is commonly thought that acne is the product of some hygienic issue--and it can be. But cystic acne has little to do with hygiene. It cannot be alleviated, often even in part, by more regular face-washing, pillowcase-changing, diet-enforcing, or topical creams. It can at times only be aggressively treated with dangerous systemic medicine.

About a year after graduating I was put on Accutane, finally accepting that this would be a necessary step in ridding myself of a force that even months prior had been deemed, regardless of treatment, to be permanently scarring.

And it worked. My lips were always dry, and I couldn't drink alcohol. But the redness faded. In the place of those awful boils, the flaky pink, the oily nose, there was an extreme disappointment: a face that was not my face. My cheeks pocked with craterous scars. I could not bear to look at myself in the mirror at all.

The world has a way of making you see yourself eventually. First in bearable ways, like in the dark reflection of a glass door at night. And when checking the rearview while driving. For months I started, slowly, and without the slightest effort, to see the face I had now. Even a pair of sunglasses on a table. The world reflects you, and you can't avoid it forever.

What happened next was unprecedented.

I stopped pressing microwaved avocado in a bowl, mixing in the lemon juice.

My scarred skin didn't change. But something in me did.

It wasn't all that bad.

I have spent two years of my life with a soapy sponge in my hands--identifying the feminine, the ugly elements--and trying so hard to scrub them away. Sometimes even succeeding to a degree. There isn't much else to say. There are things that will not change.

I had to throw away the sponge to do any real cleaning. I had to let time work itself to allow me to grow.

One difference in the narrative of learning to love my skin and learning to love my queerness is that the mirror will only show me one of these things every day. I cannot refuse the skin everyone sees, much as I may at times not especially like it. My skin is there and occasionally downright ugly and after a night of drinking I look somewhat near death. But when I drink enough water, when I am in the right light, when I am willing to see it, I now love the way my skin holds texture, how it demands to be noticed, how it is not an easy canvas for my features.

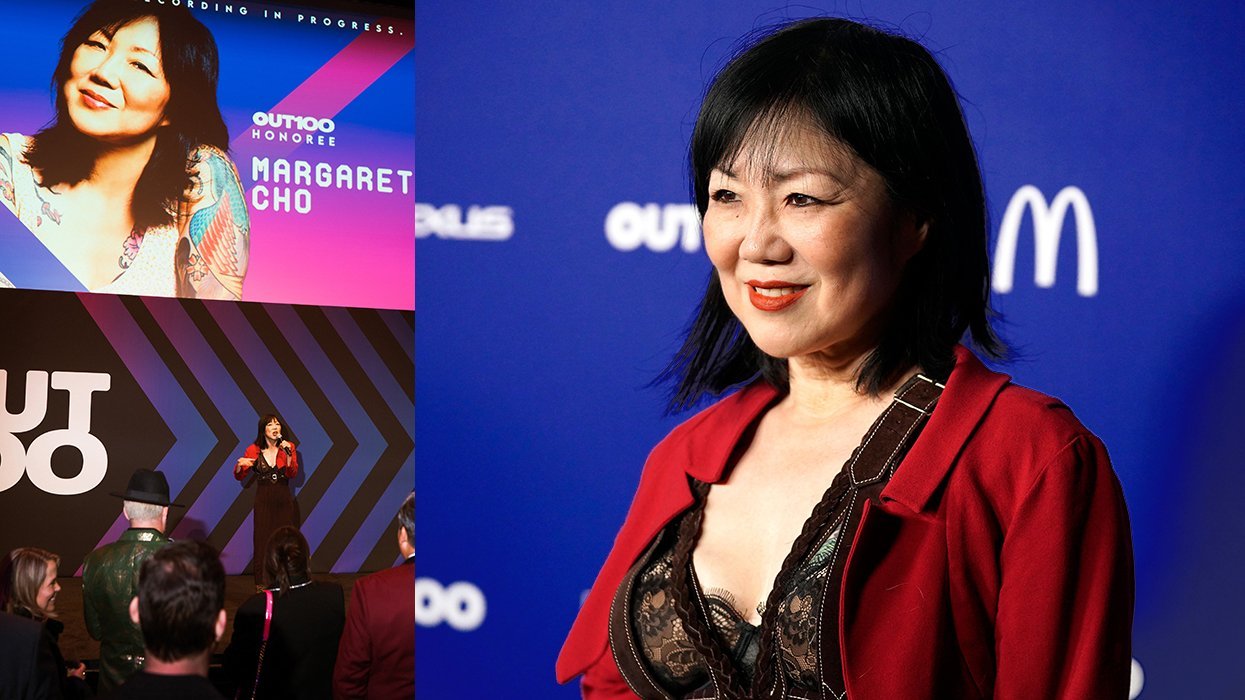

I remember once being pulled out of the bathroom at my first gay bar by a drag queen who made me introduce myself to the audience. I recall the way the light hit my face and thinking, at the time, that I must have looked awful. I was embarrassed and afraid.

As it turned out, I came to learn that my first boyfriend would have attended that very performance, and as we both laughed about the situation, talking about how much internalized homophobia we have to move past to get to ourselves, I brought up my skin.

"It gives your face character," he told me.

Which by then I believed. Because I already knew.

Peter Kispert recently served as editor-in-chief of Indiana Review and will soon attend the Columbia University Publishing Course. His work has recently appeared in Salon.com, The Carolina Quarterly, and Slice Magazine, and has been cited in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and NPR. He works with Electric Literature's Recommended Reading.