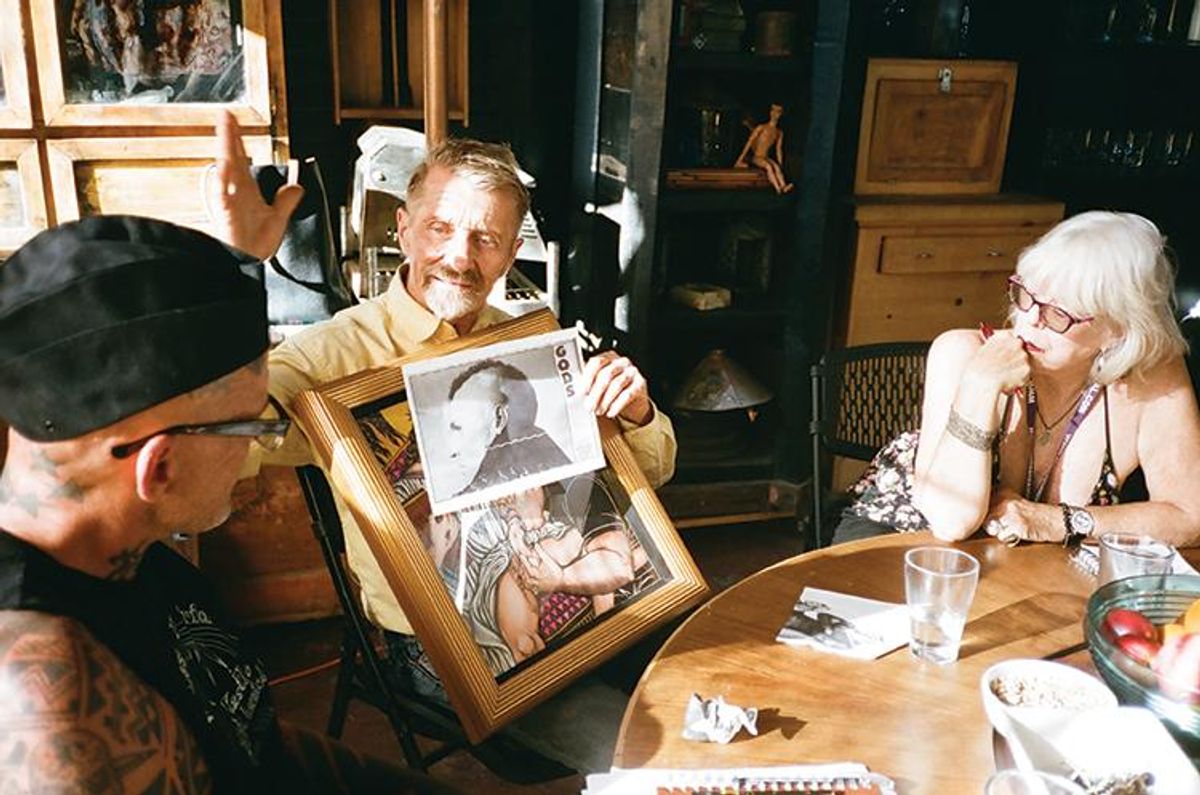

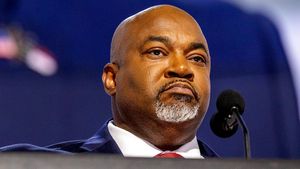

Pictured: Ron Athey, Durk Dehner, Sheree Rose. Photography by Rhys Ernst.

I was born in 1961. I was fucking in the '70s! I was aware of the cultural movements that had made me possible, but I look backwards. I never contemplated attending a Pride celebration without thinking about its catalyst, the Stonewall Riots of 1969. And being raised in a primarily black area of Pomona, I am sufficiently aware of the Black Panther Party to be able to appreciate the antecedents for today's Black Lives Matters (not to mention the style and gestures offered up in a recent Beyonce video). There were separatist movements for women, gays, and people of color. This was the era of the commune and the safe space, a time when the cruising space became affirmative in a pre-AIDS reality. For this issue of Out, I brought together a group of figures who were not only present, but also key organizers of the seminal events spanning four decades, to recall their experiences. -Ron Athey

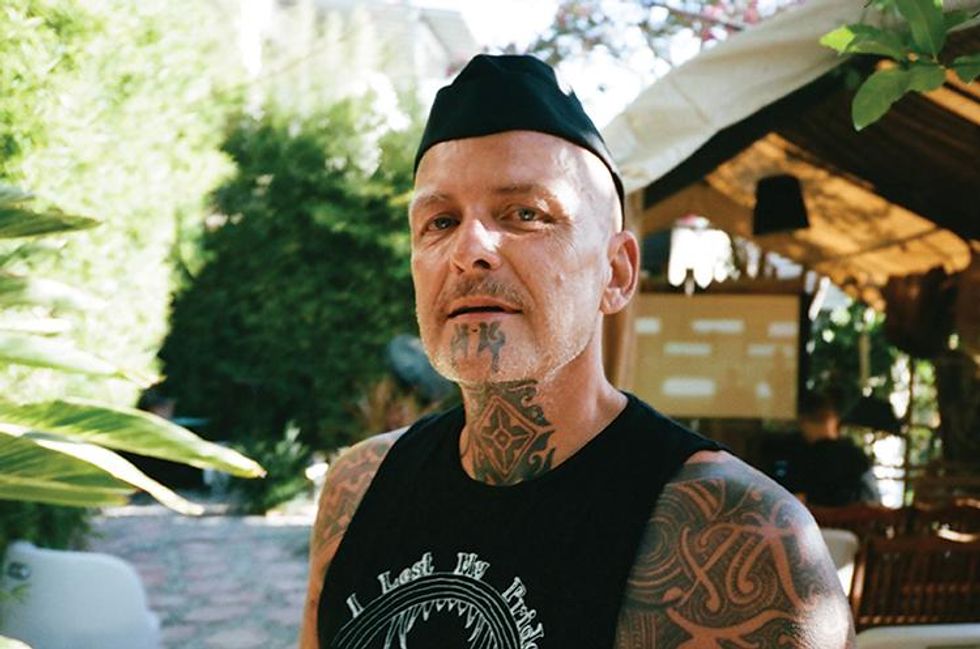

Pictured: Ron Athey

The participants include:

Toro Castano, author and co-curator of a recent show at the ONE Institute about the early-'90s phenomenon, Club Fuck!

Durk Dehner,co-founder and president of the Tom of Finland Foundation

Fayette Hauser, member of San Francisco's legendary Cockettes, and most recently involved in the Hippie Modernism show at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis

Amelia Jones, professor in art and design at USC and author of many books, including Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts

Bruce LaBruce,Canadian filmmaker and artist whose films include Hustler White and L.A. Zombie

Glen Meadmore, artist and musician, who collaborated with Vaginal Davis in the thrash-metal concept project PME

Sheree Rose,performance artist and photographer who documented the BDSM scene of the 1980s

ATHEY: I was born an abject in a fundamentalist Christian nuthouse. To understand how I could live, I had to approach literature for answers. I read Patti Smith's Babel and found William Burroughs and Jean Genet. I had to find a logic in different timelines and comprehend a foundation in order to move forward. I'm a self-educated artist and have never been aligned with an institution. I have come of age in a series of scenes starting with punk, death rock, and industrial music. I have lived through toxic drug culture, 12-step and other recoveries, AIDS/HIV support groups, and cultural movements. I want to ask you why certain social/cultural/political/identity groups start, become maximal or sublime even, and why they have such a short life span.

LABRUCE: The gay rag distributed in Toronto from 1971 to 1987 was called The Body Politic, and it was a free publication you could pick up at bars. It was hard-core socialist, Marxist, feminist -- there was such a deep political consciousness. Within five years it was replaced by the most mundane bar rag, with a lot of advertisements for local saunas, which is fine, but there was no content anymore. It wasn't a political entity. Everyone forgets that the only reason a militant movement will begin is because it has Leftist and usually Marxist and socialist roots. The black movement, the feminist movement, and the gay movement all started with those things. Then it all becomes diluted as people arrive at a position where they actually want to take over the positions of power that they were fighting against in the first place. Those roots are very strong for me. They are what united all of those disenfranchised groups.

DEHNER: If you talk to older people who lived in Echo Park and Silver Lake then, they will tell you that this whole area was called the Red Hill. That was because it was filled with artists and musicians who tended to be socialists. I was in Los Angeles in 1970, and there were Gay Liberation Front dances in the Larchmont Hall. They were like high school dances with no alcohol!

Pictured: Toro Castano

CASTANO: L.A's Stonewall before Stonewall [was] the Black Cat riots, on December 31, 1966.

ATHEY: The Black Cat is named The Black Cat again, after being Tobasco's, then Basqo's (site of Club Fuck!) and Le Barcito. The police violated a truce to stop busting gay bars that held for two years. Hence the riot. They've revived the sign and have a newspaper clipping about the history of the riots framed at the bar, but it's a nice restaurant, no longer a gay bar.

HAUSER: The people that made up the counterculture were such a tiny percentage compared to the population of this country. And yet look what happened! There was political consciousness, and a lot of print material, so we were very educated. Everybody was a socialist. No one put money in the bank or wanted to own property. The philosophy of free is not about money -- it's about sharing and equalization, equal respect. There would be a cycle of change. I first came to San Francisco in 1968, out of art school. I went to school in Boston at BU School of Fine Arts. Howard Zinn was teaching there, and Timothy Leary was doing the acid test at MIT. When I went to San Francisco, what I discovered right on Haight Street was the Body Consciousness. Everyone had assimilated all the acid experiences into their body, and they were so sexualized, it was intimidating for me.

DEHNER: I feel like I inherited that mantle you were talking about. We were creating our own culture at the time. It was very kinetic in that everybody was picking it up off of each other. I worked at an art colony in the Santa Cruz Mountains created by the inventor of the birth control pill, Carl Djerassi.

Pictured: Fayette Hauser

HAUSER: At one point I lived with John Rothermel, Sylvester, and Daniel Ware, who was my stage partner -- we were lovers. I was a funky hippie girl. If I was in love with somebody, I'd be like, OK, I'm going to live with them. The pill had just become legal, and I thought, I'm down for the adventure, man. In the Cockettes, there was no director, there was no star. If you had an idea then it was your thing. The next time it would be somebody else. It was socialistic in that way, and we shared ideas all the time. That's why it had such a quantum leap as far as the language of our genre is concerned.

DEHNER: My lover and my ex-lover and his lover, we bought this [Tom of Finland] house in 1979. In many ways it's been a communal house ever since. In 1970 I lived in Laurel Canyon and listened to Carole King. I got involved with Kundalini yoga, with Yogi Bhajan. I was doing the 5 o'clock meditation and yoga with him, and that was a weird thing, because they were not cool with homosexuality. I was doing yoga down at Melrose at Robinson, and then at the same time there were so many great cruising places. The north back alley of Melrose was all cruising. Selma Avenue was a throng. There were hundreds of guys. Griffith Park on Sundays was a ritual -- to go there and to park and to actually socialize. It was our place. Greg's Blue Dot became church on Sunday mornings -- we were looking for a spiritual base. And there was a leather bar called the One Way.

Pictured: Bruce LaBruce

LABRUCE: But at that time there was no contradiction between a spiritual path, a sexual militancy, and a political cohesion. It was all mixed together.

MEADMORE: The One Way used to play all the underground music that nobody would play. That's how I heard about it. It was a sexual bar, all black -- I got to be chums with Jim Van Tyne, and he told me about his Theoretical parties, and I just thought maybe I could perform there. I had no band.

ATHEY: Theoretical was a monthly party started by Jim Tousling and Jim Van Tyne in 1982. It was a strong mix of hard-core leather men, queer punk boys, and art-damaged people from the post-punk scene. It all clashed and meshed and then you started having these leather-daddy and punk-boy couples. It was where Vaginal Davis and Sean DeLear did their first performances, where people would try out things, like Lily Tomlin, Edie the Egg Lady, and a list of local bands.

Pictured: Glen Meadmore

MEADMORE: Lotus Lame and the Lame Flames, Edith Massey, John Fleck.

CASTANO: It was at the end of a street, kind of by itself, like a set of industrial storefronts. A guy had a warehouse there that people would go to after the One Way closed. I was 15 when I started going there, and the owner knew it and didn't mind, because the customers liked it. It was really dark and scary. The One Way was actually scary, for me.... You'd have to be really careful getting out of the car because people would beat you up all the time. It was a rough area.

DEHNER: Yes, there was a lot of killings.

ATHEY: Two blocks away, in 1989 at the Olio space on Sunset Boulevard, Bob Flanagan performed the pivotal Nailed performance, wherein he took a hammer and nailed his scrotum to a two-by-four. This was the release party for Re/Search's Modern Primitives book, a publication to which you could directly credit the massive international interest in tattooing and piercing. But the performance was more than a demonstration -- it was the sublime moment that gave the movement content. Mapping the order of events that led up to the arrival of '90s body performance, rituals, abjection, Re/Search publications, Bob and Sheree's performance work, the performers and dancers from club Fuck! -- which included adult film stars Buck Angel, Bud Cockram, model Jenny Shimizu, and the neo-burlesque stars Kitten DeVille and Michelle Hell, among others -- fully fleshed out a vital and queer scene.

Pictured: Sheree Rose

ROSE: I really feel that was one of those moments in history that changed everything, because it brought the straight SM crowd together with the art crowd -- it brought the gay crowd in. A couple of them fainted, actually, at this event. [Laughs.] There was blood. This was an intersection of art and SM. Bob Flanagan was my slave for many years. It was 1981, and we co-founded the Society of Janus here in Los Angeles. Cynthia Slater started that club in 1979 in San Francisco. What made that club special was that it was an umbrella organization. It didn't matter if you were straight, gay, black, white, trans -- we didn't care, as long as you were into SM and it was safe, sane, and consensual. It was the first time that it was brought out to a larger audience, because usually, straight people who were into SM were very closeted.

ATHEY: Absolutely. But there were a few things leading up to this moment, and Nailed was a huge kick-off. We were also soon into the AIDS pandemic, so there was constant death, and mega-empowerment via activists through ACT UP and then Queer Nation. I couldn't stop and think where my performance work would "sit" in this moment. Not only my closed inner circle of friends died, but colleagues and idols and mentors. The deaths of David Wojnarowicz and Leigh Bowery hit me hard, and I made work about it. Issues came to the forefront that I explored -- not just identity but the philosophical premise of healing. So how to take this on the road? For the longest time I found performing in art centers so dry compared to club audiences. I liked drunks and people off their faces on ecstasy that didn't come there to see me. It can be an intervention.

ROSE: As an artist who's always been considered an outsider artist, I'm now collaborating with Jeffrey Vallance. He suggested we have the Saint Bob Flanagan S&M Chapel. Someone like Jeffrey, a wonderful artist and professor, who's white, straight, and a very well-regarded artist, we're collaborating. The point is, it's not just us as outsider artists -- we need allies who are not us.

Pictured: Amelia Jones

JONES: Well, I have serious questions about this. How much do we want in the mainstream institutions?

DEHNER: A masterpiece of Tom of Finland's was going to be donated to MOMA, and because it had fist fucking in it, they actually rejected it...and this is in 2006. They felt it could actually jeopardize the whole gift that was coming from the Duder-Rothschild Foundation, and so they pulled it. All of those curators should be aligned with us.

ATHEY: But the whole point of looking at this through the lens of previous countercultures -- do we only feel relevant when embraced by big museums? What about spaces like LACE [Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions] or Barnsdall-Los Angeles Municipal Gallery?

JONES: Sometimes it should be at the Barnsdall. That's exactly the point.

HAUSER: You can turn it around. This is what I'm seeing with the current interest in counterculture from big institutions. For years the mainstream demonized and trivialized counterculture: Dirty hippies! Stupid hippies! All of a sudden high culture has turned around to re-examine the Cockettes and other hippie counterculture movements. So this is a platform. It's a seminal moment to get the message out, and get paid as well. This is the time to be anarchistic in a nonviolent way. I want to participate. I want to change the mainstream -- change the museum dialogue -- by being involved.

DEHNER: Tom of Finland Foundation has been around for 35 years, and our core supporters were gay men, up until 10 years ago. As gay culture started to break down that support went away, and we had to be resourceful. We started doing Tom of Finland products, and now merchandising is one of the main vehicles through which younger people discover Tom. We transformed the country of Finland through this product. They really didn't dig Tom of Finland. Now they have a Tom postage stamp.

ATHEY: Pluses and minuses there. Over-merchandising, it's like being a porn star and doing too many flicks in one year. No one wants to look at you anymore. There's a risk of totally losing control of context or becoming kitsch. It depends on the content. I think Tom product refers to but isn't standing in for the archive. A lot of us here are talking about working/living archives, sometimes archives of a scene rather than their own art.

CASTANO: There's a big difference between Tom of Finland, who makes these objects, which become explicit commodities, and the club Fuck! exhibition I co-curated with Lucia Fabio. If you look at the objects, there's very little story there. I think these are important conversations both about archives and about showing -- how do you show what happened at Club Fuck!?

DEHNER: The reason the Tom facility got started was because the artists couldn't find venues to show their work -- it was too sexual in its content for the galleries. And so we built our own collector base and we created our own exhibitions. I want to actually leave this property for everybody to continue to take advantage of and nurture and take care of. If it's just an archive about a period in history, it's useless. I mean, it's not useless, but it's so much more valuable if we can actually open it up and let new artists delve into it and swim into it and find things and reinterpret it, and let it become a new fountain for them.

CASTANO: Amelia started to touch on this, the cultural conditions and how they've changed. Is it late capitalism? Is it the fact that we're 40, 50 years past these social movements? I'm interested in knowing the bridge between countercultural movements from then to now.

JONES: I think we're very late capitalized, but I also think some really cool things go on, and we have to empower ourselves to understand the structures now, while also learning everything we can about these past countercultural movements. But it's not going to work try to to do what you were able to do in San Francisco in the '60s.

DEHNER: Where this all ends is that I will always remember the hammer through Bob's cock. I will always remember Ron's crown of thorns at LACE, dripping. It felt like a celestial experience. What I'm trying to say is, in the end, what we remember is visual. Something is still happening here in L.A. It was happening here when I arrived in 1970, and that L.A. still has a ground where young artists are excited about being here, and they find access to things on whatever level that they can afford, and they're creating things here.

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right