Jill Soloway's groundbreaking Amazon hit Transparent is a shrewd, affecting portrait of a transgender woman who comes out to her family at the age of 68. But the show, which has won Soloway two consecutive Emmys for best directing for a comedy series, has been more than a revelation for its viewers -- it has completely reshaped its creator's own perspectives on gender. "I look at people who don't identify as either male or female as the future of the future of the trans movement," says Soloway, whose own father came out as a trans woman in 2012. "There are a lot of people who see themselves as both, or either, or neither. I'm coming to a place where I feel like that's the way I'm going to identify soon. I stopped being straight and stopped being femme, and all this happened over the past five years, totally changing my way of moving through the world."

In March, Soloway sat down with author and activist Van Jones, the host of CNN's The Messy Truth and himself an outspoken storyteller. Here, the pair, who were both in Austin for South by Southwest, discuss living in a post-Trump world, toppling the patriarchy in Hollywood, and Soloway's new series, I Love Dick (premiering May 12 on Amazon).

Van Jones: One of the most important movements of this century is the movement for transgender liberation. Your work has been an entry point for many people's understanding of trans issues. Do you feel that responsibility as an artist?

Jill Soloway: A little bit. After my dad came out as trans, I thought, I'm going to write a 30-page script to make me feel better. It was this imaginary world I could live in: creating little dolls, giving them names, creating a sense of reality that made me feel safe. I used the pilot for Transparent to come out to people about my father. It was this intimate tool to help me with shame. Then it became this thing. I remember this moment of standing in my bedroom and thinking, I'm gonna have this mantle now -- this mantle of leadership. Get ready.

VJ: I remember talking to Prince, and he said something similar: "I didn't know I was changing what was possible in terms of gender expression. I was just trying to be myself, to get free." That's the power of art and authentic expression. You could just retire -- you're already gonna be in the history books. But tell me about your new show, I Love Dick.

JS: It started with the playwright Sarah Gubbins saying, "You gotta read this article about this woman Chris Kraus, who wrote this feminist book, I Love Dick. We both became obsessed with Chris and with this idea that a book about a woman finding her voice could be called I Love Dick. You know, dick means patriarchy. Patriarchy makes women constantly doubt their voices. If you're a woman, a person of color, or queer, you always have to step around white, hetero patriarchy to be accepted. What happens when you're always attempting to get access to the culture makers and not actually giving birth to the culture? What does that do to our sense of self? That's what it felt like for me as an 8-year-old girl in the classroom looking at all the presidents, being like, "Man, man, man." It's similar for people of color: "White, white, white." It's such a shattering feeling for a child. There is no story to explain why you're "less than." You just are.

VJ: And sometimes when women try to speak out, it's like, "Awww. It's so cute that you're upset about it."

JS: Yeah. Kevin Bacon, who plays Dick, says to Chris [Kathryn Hahn]: "You know, women make such shitty films because they're always working from behind their oppression." Chris Kraus is a real person who had a husband, Sylvere. Chris fell in love with Dick, and she started writing him these obsessive letters. Dick was like, "Leave me the fuck alone." And at some point Chris realized, I'm not in love with him. I'm not crazy. I'm a writer. This is my book. This is my voice. With this book Chris took that abject feeling of female-ness and being other-ized and dove into it. Within that shape of otherness she found her voice.

I also liked the dynamic of a woman and her husband obsessed with a guy. We never see TV shows where the husband's in on it, where he's like, "Let's talk about Dick." Which is one of the most dangerous things to say in this country. It's pretty obvious all men watch porn. Men look at dicks all day long! [Laughs.] Straight men watch other men's dicks all the time, but they never talk about it. I love exploding that myth -- like, "This couple talks about this man, they both get turned on, this is heterosexuality, and it's fine."

VJ: In your talk at the Makers Conference in February, you said, "I have to try to offer myself white male privilege and wear it through the world." How do you do that?

JS: I guess with my body. From the age of 16, I started putting on makeup, trying to be cute, and dating men, and I didn't question it. That was just who I was. My sister, Faith, is a lesbian. So I was like, "She can be the lesbian, and I'll be the straight one." But I'd hang out with dykes and be like, These are my people. I had a lot of lesbians say to me, "You're the straightest lesbian I've ever met." Like, "Jill, you're queer, what are you doing?" People were always trying to out me to myself. When I was young and single, I'd go crazy when straight women were talking about high heels and this kind of "attracting-ness" -- like, turning themselves into an object. I was enraged about the book The Rules: "You don't want to scare a man, so you have to pretend X, Y, and Z." When my dad came out, I was like, Maybe this is what's been going on. I may not be a cis woman. I may not be like all those other women. Because my parent came out as trans, it allowed me to recognize that there was a lot of gender dysphoria for me, a lot of gender trouble.

A lot of women have these same feelings: "I don't want to fucking wear Spanx. I don't want to do the fucking hair and makeup thing." I look at you, Van, and I think, Nobody spent an hour making your face look acceptable to be on TV. They put some powder on you, you go. But for me it started to feel like, what's wrong with my face that I can't just talk? What's wrong with my body that I have to hold it in? What's wrong with my posture that I need high heels so that people can listen to my ideas? Why aren't my ideas enough? I was getting hair and makeup in a bathroom in Germany, doing Transparent press, and a makeup artist was coming at me, and I was starting to feel like, What do you have against my fucking face, dude? Let me go downstairs and talk to the people. That was really part of my coming out: being able to sit across the room from somebody and say, "We're gonna talk about ideas." It wasn't like in the past when I'd feel like, "Am I cute?"

VJ: Your agenda is liberatory, but it's also disorienting for people who've never heard the word "patriarchy," who don't know what intersectional means. They just see somebody trying to change how things have been. Since November, I've spent time in the red states talking to Trump supporters. I'm actually developing empathy for a lot of these white, cisgender, heterosexual, middle-aged men, who are often unemployed or underemployed and in a lot of pain. Your responsibility is to topple the patriarchy, but the people at the top of that pyramid are having a hard time with it. What do you think about that?

JS: Well, I don't think they're at the top of it. I think they believe they're at the top. That's what Trump offers them: "Hey, at least you're white and a man." I'm with you. I'm interested in a common language about faith and God, and actually feeling somewhat bombastic about love lately. You're never gonna get anywhere saying, "You other-ize people because you're bad." They see themselves as the other-ized.

VJ: Exactly. Part of what you're seeing is, "I'm right and you're wrong." We're not talking to each other -- we're talking about each other. Everything is stuck right now. It is thesis, antithesis, thesis, antithesis. Fox, MSNBC, Fox, MSNBC. Back, forth, back, forth. There's never synthesis, that breakthrough into a new space.

JS: I think it's coming, though. I just hope I live long enough to see what happens if we can have this global synthesis that holds something as simple as love. Because, and I'm sure you notice this when you go to meet people, most people want to be in love. They don't want to be in pain. They want to sit at their kitchen table and be sweet and have people be sweet to them.

VJ: Liberals and conservatives can both be very colonial in their conversations. They first divide the country into red and blue, and then they assign their side superiority, while the other side is inferior. Then you either have to conquer or convert. You have to beat these people or, you know, "They just need to listen to more NPR and they'll be like us." There's no love in that. I'm trying to find a different conversation that's not "I'm right, you're wrong," but instead "I don't have to change you or convince you. I want to understand you, and I want to be understood." What I'm wrestling with is, if you're a progressive or a liberal, your hope is that we're the enlightened ones, we're the --

JS: Saving force.

VJ: Yeah. But I'm seeing that we're actually participating in this pattern: Both sides keep doing the same thing over and over again, and they think it's a conversation, but it's not. I think nobody wants to hear that, because basically I'm saying liberals are helping Trump. But right now, we're in danger of fighting polarization with polarization.

JS: When you talk about this polarizing, this binary, this either/or, I look at the primary elections and I'm like, My God, we were beating the fuck out of each other in the name of Bernie and Hillary. All of these supposedly loving, good people who don't like conflict -- we were learning how to kill each other, using Facebook to do so. And nobody stopped and said, "Why?"

VJ: One of my teachers told me that in a normal civilizational moment, politicians, business leaders, and generals are basically in charge. But when you get into a civilizational crisis like we're in, it's the artists, mystics, and spiritual people that wind up with more responsibility. The intellectuals wind up with more responsibility, for which they are totally unprepared. That's where we are right now. We have artists like you.

JS: Which one are you?

VJ: I'm a pundit on TV. [Laughs.]

JS: What if you ask one of your new friends in Trumpland, "What do you think about the 'pussy grabbing' thing?"

VJ: They're appalled. These are good people.

JS: But they're still glad for him to be president because they think he's going to shake things up?

VJ: This is the hardest translation for me. They say that it's like anything else distasteful or somewhat titillating: There's a bit of joy in the transgression against the liberals' delicate worldview. But then they're also parents and grandparents who wouldn't want their kids to say the things he says. They're complex. They're not these cartoons. But you know what? When Trump tweets all day, the liberals don't even see the beautiful tweets.

JS: What are Trump's beautiful tweets?

VJ: He talks about his effort to keep jobs here. If you don't have a job, or you don't have a job you're proud of, to know the president called somebody for you? That's huge. We're so busy trying to find the crazy tweets that we don't even see that. Now, Trump is a jackass who is the worst possible leader for this moment, except maybe he's gonna bring out a pro-democracy movement, which we need. If he does 99 bad things, I'll say they're bad, but if he does one good thing, I'll say it's good. That's where I'm trying to take some risks. As a liberal, it's so cheap and easy to be a bigot.

JS: Your willingness to step into that third space and say, "I'm not either/or" -- that's why I want to find a new word for you other than "pundit"! [Laughs.]

VJ: "Storyteller" is a word I've been trying on. You're actually doing it, and it's inspiring.

JS: Did you know Trump was gonna win?

VJ: Yeah, pretty much. Actually, I thought the 'pussy grabbing' thing would hurt him with the Evangelicals, but then they came back around based on the choice issue, the abortion issue.

JS: What do you think about that? How is that ever going to get solved?

VJ: We just have to beat 'em. Some things you can't compromise on.

JS: I have an imaginary compromise on it. I will make a trade. I'll give up abortion if everybody else gives up guns. A world where there are no guns means a world where there is no war. Pro-life? That means no guns, no war. Maybe if there's no patriarchy, there aren't unwanted pregnancies.

VJ: What I liked about Nelson Mandela as opposed to a Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr. is that Mandela led Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress. He wasn't willing to get pushed around forever.

JS: So you feel armies are necessary?

VJ: Sometimes you have to draw a line. For instance, Gandhi's prescription for Hitler was for the Jews to turn themselves in and, in doing so, shame the German people into replacing him.

JS: That didn't work.

VJ: Obviously I don't believe in using violence in the U.S., but I'm very glad General Patton had a different answer for Hitler than Gandhi.

JS: Do you know about the people of Rojava?

VJ: I've never heard of them.

JS: It's a women-led, feminist, egalitarian, stateless army in Syria, and they're fighting ISIS and using a council-based way of solving problems. The women are really fashionable and carry guns. So they started to move me around guns a little.

VJ: I'm not trying to make the case for guns or not guns. I'm trying to leave space in the conversation. Sometimes your opponent can be won over, and sometimes they have to be run over.

JS: Let me ask you about Trump's America and the people so excited that they might have a job. Don't you feel like in this world of artificial intelligence and self-delivering pizzas that, actually, there isn't going to be work for people?

VJ: I haven't seen Occupy Silicon Valley. Wall Street is a massive problem, but in some ways it's just financing the real problem, which is on the other side of the country, which nobody's even talking about.

JS: We're also so new at figuring out what it means to translate our feelings onto the screen. I feel like what's happening with Silicon Valley, and with the ability we have with a phone to create an experience, can't create this experience -- this feeling we have now sitting in a room together.

VJ: So how can men, in particular gay men, be involved in toppling the patriarchy?

JS: Well, you talk about the LGBTQ movement, and when you start talking about the trans movement, there's a new supposed enemy: white cis men. That includes gay men. What does it mean to be cis, to identify with the gender you were assigned at birth? Well, that does confer a whole lot of privilege. I'll be as radically honest as you are: When I look at the patriarchy, at least for me, in the television business -- the guys on the golf course, on boats, getting a tan, talking about audiences and Nielsens -- gay men were in there too. It wasn't just straight men. That's because our culture worships masculinity. Gay men have had access to a lot of rooms to which women and trans people don't have access.

I'm always talking about my struggle as a feminist, but when I'm working with African-American women, I have to ask myself, Where is my privilege from being white? I do that by asking, What is my dream conversation with the white straight men, the Steve Levitans or the Aaron Sorkins, who have seemingly run television? I just want them, the next time they see me at a party, to come up and be like, "I've been thinking, and over the past 20 years I opportunity-hoarded for all the men like me: white, Jewish, funny men. I hoarded the opportunity and shared it with them, and you didn't get hired a lot of those times because of that." Then I think, That's what I should do with my African-American sisters -- say, "I recognize that over the past 15 years, I have been hoarding opportunities for white women." I would ask gay men to do the same thing, to say that very hard thing.

VJ: It's such a powerful thing to say, because once you get into these tribalized binaries, confession is treason.

JS: Separating that confession from shame is huge, because people suffer from so much shame.

VJ: Yeah, if you're a person of color, LGBTQ, a woman -- a minority where you're one down -- shame is massive. You have these sore spots and think it's unfair to ask someone who's one down to confess. And yet it's absolutely necessary.

JS: "Why do I have to confess when they're not confessing?" That's what everybody's doing.

VJ: You've become one of the great American storytellers. What other stories would you like to tell?

JS: I don't know if it's a Jewish thing, but I have this feeling of "I'm in trouble, I did something wrong, I have to. Another TV show, hurry, another revolution. We're gonna fix this and change the world." But what I think I really want to do is start to tell the story of being OK with myself and trying to love myself. We just talked about this idea of being "one down." I think for a lot of people that feels like a rock coming down a hill, or a snowball running after them. I just want to get that thing off me, and just be like, It's OK. The world's gonna be all right. I don't have to do it all. There can be a revolution, but I don't have to start it. I've done enough.

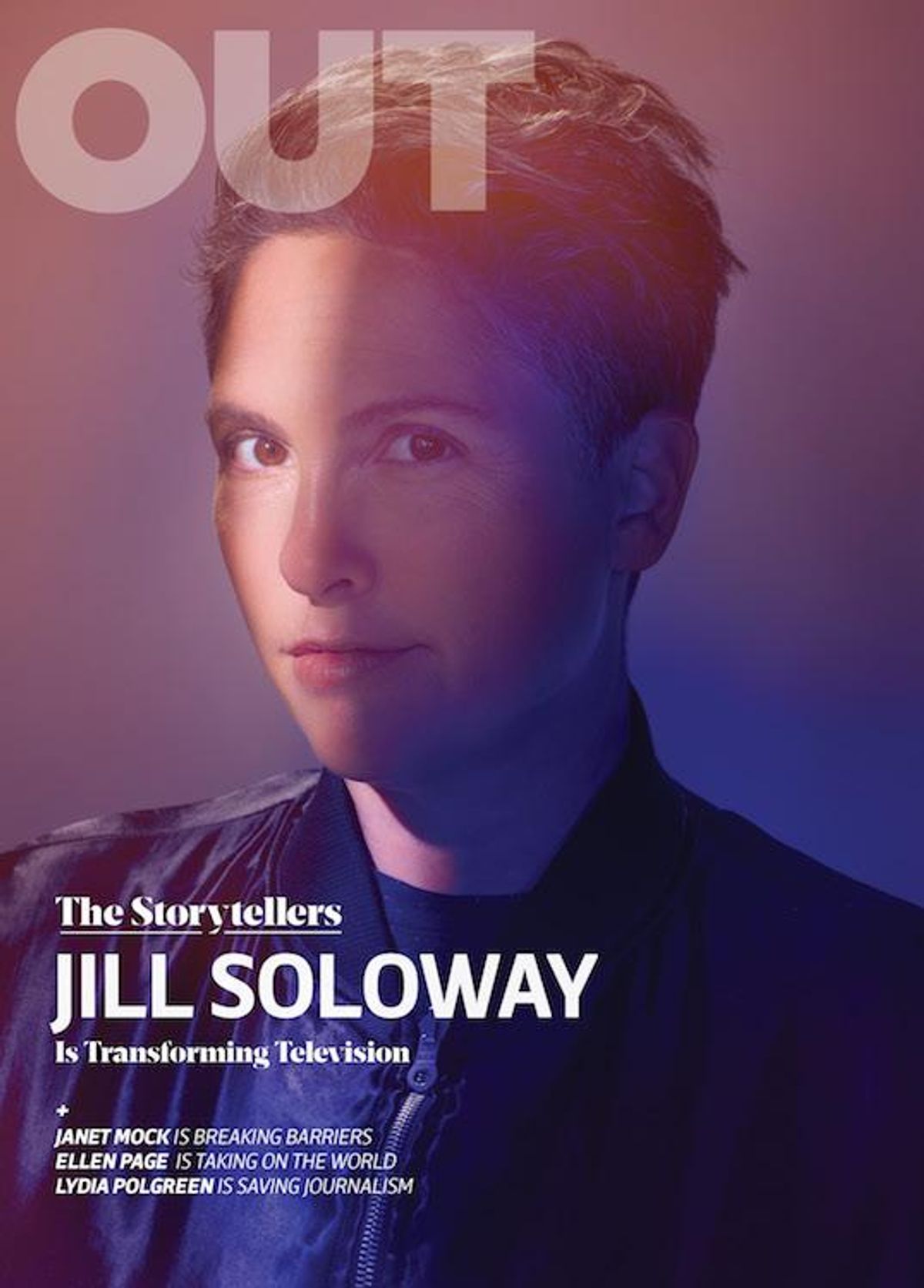

Photography: Jill Greenberg

Styling: Alison Brooks at Exclusive Artists

Hair & Makeup: Molly Greenwald (The Wall Group)

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of Out. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.