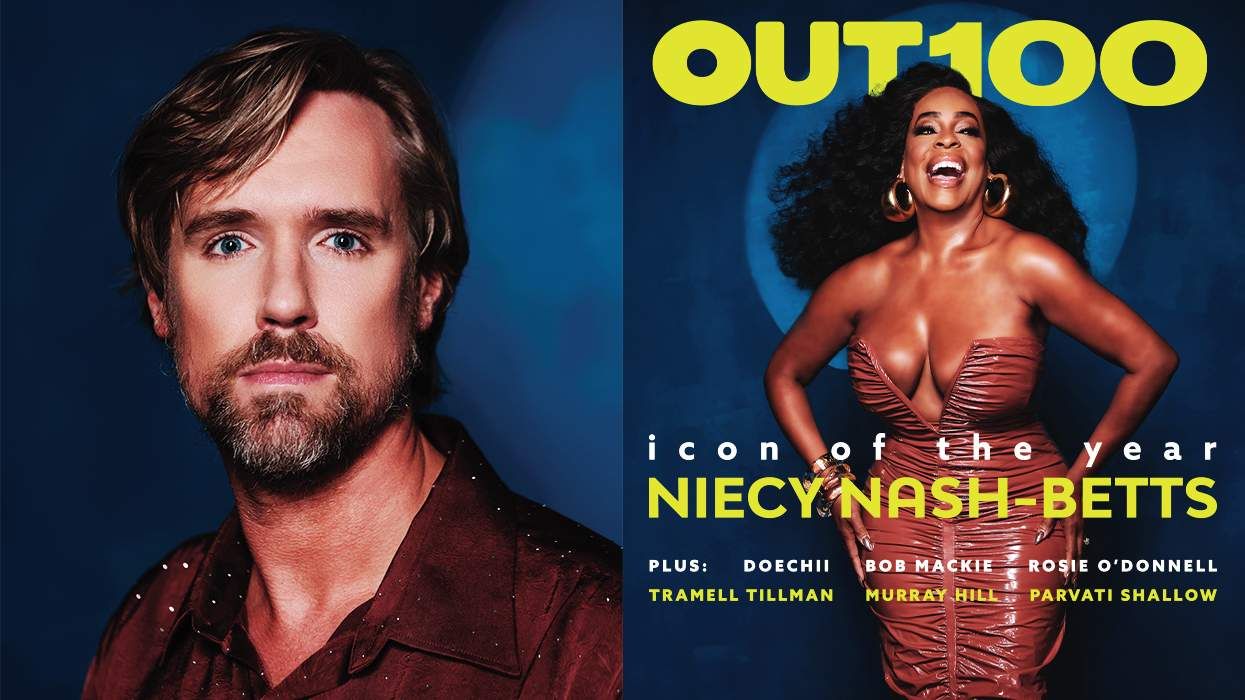

Editor's note: This conversation took place in March 2017, before allegations surfaced against PWR BTTM frontman Ben Hopkins.

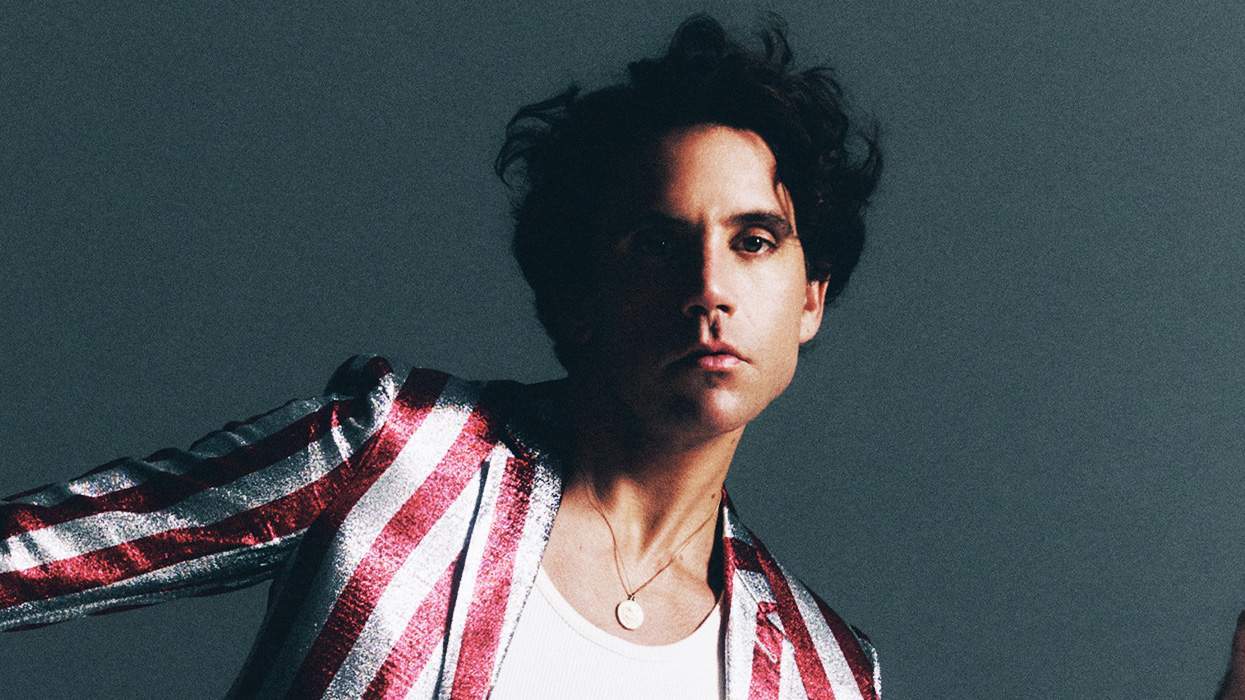

What does it mean to be punk in these turbulent times? If you're Ben Hopkins and Liv Bruce, the New York duo known as PWR BTTM, it means slipping on a flowery dress, reaching for the lipstick, and throwing caution -- and a shit ton of glitter -- to the wind.

It also means crafting sly, infectious, heartfelt anthems about otherness, confidence, and that dick who won't answer your text. On their new album, Pageant, the former dance and theater majors preach the gospel of the self, and the thrill of its mutability -- both identify as queer, and Bruce also identifies as nonbinary and transfeminine.

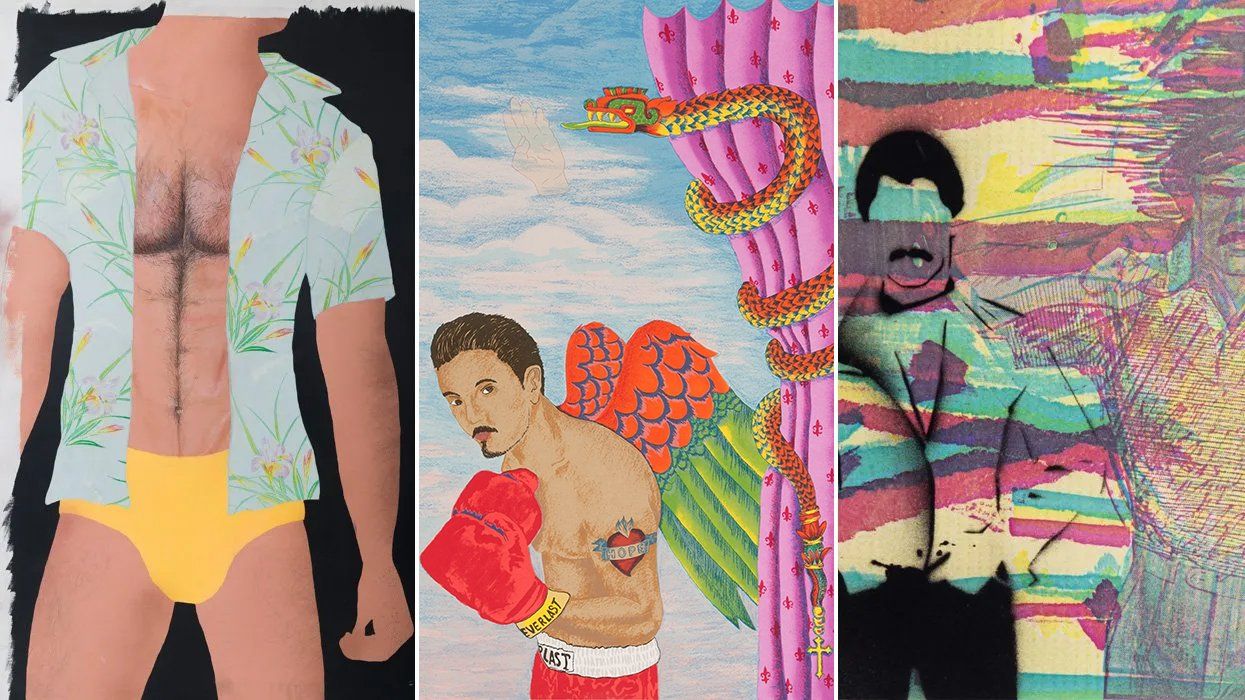

Related | Gallery: When PWR BTTM Met Priests

PWR BTTM's impassioned pleas for self-love echo the incendiary war cries of Priests, the Washington, D.C.-based punk outfit made up of queer singer Katie Alice Greer, drummer Daniele Daniele, trans bassist Taylor Mulitz, and queer guitarist G.L. Jaguar. Their debut full-length, Nothing Feels Natural (out now on their own label, Sister Polygon), pairs mordant, sneering lyrics about vacuous consumerism and patriarchal strangleholds with a punchy mix of surf rock, jazz, barroom piano, and riot grrrl angst. The result is one of the most electrifying and vital records of the year.

In March, just before both acts played South by Southwest, Priests called PWR BTTM to talk about the importance of DIY spaces, their favorite protest music, and why the personal, especially when writing from a queer perspective, is always political.

Ben Hopkins, PWR BTTM: So what's the political climate in D.C. been like since the election?

G.L. Jaguar, Priests: I've definitely noticed a change. One of my good friends, a bartender, has been called racial slurs at least five times since the day of the election.

Taylor Mulitz, Priests: Crimes against trans people in D.C. have gone up 100%. I saw that statistic yesterday. The D.C. police department put out a statement that was reported in the Post last week that said hate crimes have gone up 40%.

Katie Alice Greer, Priests: And recently there's an epidemic of young black women going missing. It's disconcerting, but these stories are being reported much more because of people sharing them on social media. How are things in New York?

Liv Bruce, PWR BTTM: I've seen articles about the crackdown on show spaces -- DIY show spaces in particular. After the fire at the Ghost Ship [an art collective in Oakland, Calif.] there were posts on 4chan that were like, "These places are where the left congregate." Sometimes when the fire marshal shows up, they had been given tips by anonymous alt-right trolls who want nothing more than for a DIY show space not to exist anymore. But if they want so badly for it to be shut down, that's a glowing testimonial that what we do works in some way. It's super important for us as bands to keep doing what we're doing.

Greer: Totally. It's important for these spaces to exist. If the only channels for making music are these incredibly professional, slick places where music is used as a backdrop to sell alcohol, that's gonna dramatically influence the way people are making music. I think our bands felt like we could carve out space to take risks and do something different, but I worry about the future for anybody making music, where there are only these narrow channels for expressing creativity.

Daniele Daniele, Priests: After the Ghost Ship fire, these trolls were like, "Yeah, burn in hell." I've seen this homophobic backlash, and it's so frightening. It makes me so angry.

Hopkins: People protested against PWR BTTM in Jackson, Mississippi, a week after the election. We just went there to play a show, but there were religious extremists with signs that said, "You'll burn in the lake of fire," which to me sounds amazing.

Daniele: That sounds nice. [Laughs.]

Bruce: Listen, I'm not a politician. There are actual activists and organizers who go on the street and knock on doors and do real political work. Ultimately, PWR BTTM is just a band, but a show space is a place where people with similar ideas can get together and become friends. You can meet someone who can make you feel less alone.

Daniele: Like a lot of young people, I found a community in DIY music spaces. Living in New York, I'd go to shows where I didn't even know who was playing because I knew my friends would be there. I wanted to come back every night.

Greer: I'm bisexual and a cis white woman, and I find myself thinking about how privilege functions in different spaces and what I can be doing for my community other than reinforcing the shitty power dynamics that already exist.

Bruce: I mean, Ben and I have privilege in that people can choose to see us as just two white boys playing around in dresses. That sucks, and it erases huge parts of our identities, but it's a way to start a conversation with someone who might otherwise be unable to see queer people as people because of their own privilege. I thought about this so much last year doing tours supporting other bands for a lot of audiences that weren't our typical demographic. When I was selling shirts to them at the merch table, they'd misgender me every night. It was clear they weren't completely understanding, but I had to remind myself that this brings them in and there's something they can learn from having seen us -- what it means to be a nonbinary or trans person, or to listen to queer people when they talk. That's productive. I see a lot of us shifting gears out of the Obama administration, when we were concerned with things that to most Americans seem like niche causes, or with fine-tuning our agenda. Now solidarity is so important across different political views.

Greer: You talking about being misgendered and having your identity erased reminds me of how strange it is to be a performer and be willing to be objectified: Every night someone's looking at you and seeing this flattened version.

Hopkins: It's so easy to be viewed as an art object because of the way you look and dress in a performance space. I feel like I'm becoming more and more glamorous, but when PWR BTTM started performing I would, like, eat cigarettes at shows. I get a very different reaction now that I have glitter on my face.

Greer: Even when I was presenting less this way, I was always pushing the "femme" agenda, for lack of a better word. It's so strange how when you're covered in glitter or wearing pink or looking glamorous, you get more attention. But a lot of times it's an attention that I think is either objectifying at best or dehumanizing at worst. Part of my presentation is just because I'm into pop stars and Nicki Minaj. It's a very simple idea: asking people to see me as a multifaceted person and also as someone who wears makeup, fake eyelashes, and six-inch heels.

Daniele: It's crazy that in 2017 you're still complicating the narrative by being like, "I'm presenting as high femme and I'm powerful and I'm smart." I remember when Katie started dressing more femme, some men were like, "Do I take you less seriously now?" Like, really? I thought we got over this with Mae West, motherfuckers.

Greer: A very well-established musician in our scene whom I love dearly told me how it seemed like I was changing directions, musically, from the rest of the band. We were playing the same songs -- I had just gotten my makeup done at the MAC counter and was wearing a wig. It was so strange. But your narrative gets flattened too -- you become just boys playing with dresses. Even that goes back to the idea that femme-ness complicates the narrative.

Hopkins: When we started touring, people would think it was fine to stick their hands up my skirt. It changes the way people interact with you.

Bruce: We're talking about what we as performers can be doing for the community, which makes me wonder: What is some protest music you really like? I'd say my favorite moment is Sinead O'Connor ripping up a picture of the pope on TV.

Daniele: Beyonce. That's the best protest music right now. She's such a badass, on a cop car, like, "Fuck all y'all." When "Formation" came out, I was like [shrieks].

Greer: Anything can be political, depending on how you're talking about it. We're all protesting this bullshit world every single day just by continuing to live. But I do love this folk artist Barbara Dane, who put out a record called I Hate the Capitalist System in the '70s. It's just really dark protest songs.

Hopkins: PWR BTTM never set out to make protest music. Obviously we write about things we care about, but I think music can just be a fantastic soundtrack to political work. A song can make you feel empowered to do actual political labor.

Greer: We live in a culture that is so deeply influenced by monotheistic religions, and so we deify pop stars and our favorite artists -- we put these expectations on them. Instead of thinking of you as just a musician, people ask, "Well, what have you done for this cause?" We live in this super-performative era where everyone confuses their characteristics as their selling points. Right now, activism, feminism, and all of these different -isms are very in. Capitalism does this to all of us: It uses our passions against us and makes us function as people who are selling these flattened concepts rather than just making music that interacts with them.

Hopkins: We become like a brand.

Greer: Right. We all exist under capitalism. Our hands are already dirty and complicit in this machine just by existing, so what can we do to try to mitigate that or reverse it in some way?

Mulitz: What you are OK and not OK with participating in, who you get money from, which things you use -- there's no hard line to draw. It's really amorphous. It's pretty much all bad.

Bruce: Sometimes I encounter someone on the Internet taking a musician to task for not being pure or untainted enough. I'm like, "Are you typing this on a computer you built yourself? Do you have solar power in your tree house that you built from trees that had already fallen down? Do you live on foraged nuts and berries? Like, what's your deal? I want to know." [Laughs.]

Greer: I think a huge problem with the left is an obsession with purity and with trying to silence other perspectives. We should be able to have conversations about what we're doing right and what we're doing wrong. We're all fucked up just by virtue of living under capitalism. We all work in a fucked industry, but so do people in the restaurant industry and people on Capitol Hill. So let's move forward. I'm not just gonna stay home and knit because that's the only un-fucked-up thing I can do.

Bruce: I do want to be fighting for queer liberation, and other liberation, but you can't keep going if you don't have time for you. I think it's important to show up in person for the causes you believe in, but it's also important to remember that everyone needs space. You should focus less on keeping attendance at the rally -- being like, "Who was here? Who wasn't?" -- and more on getting yourself out there if you're up to it, and if you're not, figuring out what you need.

Hopkins: Our theme of "the personal is political" has been around forever. That isn't something PWR BTTM drew on a giant chalkboard -- like, "OK, how are we gonna accomplish this today?" It's more this idea of, "I'm a queer person and I'm gonna write a song." There's a song on our record called "Oh, Boy," which is about a guy I hooked up with who lived across the street from my apartment. I wrote "Big Beautiful Day" about my friend who was fat-shamed at a doctor's office. Those songs are about more than just that, but the impetus for them was a very personal experience.

Greer: As a band, Priests is trying to erase this notion of "You're either yes or no, it's black or white, it's personal or political." We live in a much more nuanced, colorful world, and things are often a lot more complicated than just a sound bite. I think if you're a rich, cis, hetero, white man, maybe it sounds weird to be talking about how radical it is to make space for personal experiences, because your personal experience is being catered to you all the time. But for anyone who is not that, getting our voices and experiences out there is a very political function.

I was thinking about what you said earlier, how people come to your show and they don't really understand PWR BTTM, but you're like, "This is their entry point into it." One thing about art is that it's flexible: A personal narrative can unite a group of people. It has the flexibility to be all these different things. That's also its weakness: You could be trying to say something, and someone could read it as something totally different. But the strength of art -- why it can be this entryway, this doorway, this thing that unites -- is that it has the flexibility to be both personal and political at the same time. It can be left and right, any combination of feelings, emotions, or colors. What makes art scary and dangerous is that it can't be pinned down. But what gives it strength and makes it fly is that it can't be pinned down.

Bruce: Thank you for saying that. There is music that can't be pinned down, and that's part of its power. To me, what makes music protest music is that it has a specific message. Like, the old song "M.T.A." is trying to convince you to vote for the guy who won't raise the train fare so you can get this guy Charlie off the train. PWR BTTM isn't really making protest music.

Greer: Protest music is, and it sounds scary to say, akin to propaganda. It's not "the personal is political." It's "do this." It's instructional, indicative, didactic.

Bruce: Maybe one of the weaknesses of protest music is that, in hindsight, after the specific cause it addresses is not in the foreground anymore culturally, it can seem dated and hard to apply to a new struggle. But it also helps memorialize a struggle that might otherwise be easy to forget.

Jaguar: I really like the idea of music being the soundtrack to a revolution. I grew up during the George W. Bush administration in D.C. and was constantly going to protests, and there were bands like Black Eyes, whose music wasn't overtly political, but it felt like the soundtrack to what was going on at the time.

Hopkins: Priests, I hear your song "No Big Bang," and I can contextualize it in the moment, but also in 20 years, because it's more than just the event -- it's about the idea of the event. Protest music seems to be a part of human nature -- these are the kind of things that will last forever. Like Bikini Kill -- when will there not be a need for a rebel girl? The girl will change, but there will always be the necessity. It's about the particular event, but it's the energy put into it that speaks to something bigger, that makes it more than just one protest.

Greer: I think of Patti Smith's music as protest music. Most of her songs are not topical or trying to push an agenda, and they're not super direct, but her music has that spirit you're describing. It's always relevant.

Daniele: Nina Simone's "Mississippi Goddam" is so topical, a memorial to a moment. It's maybe the best example of that ever. But at the same time, it's timeless -- and not because racism is still such a fucking problem, but because there are so many times where you have worked and worked and thought you got somewhere, and then something happens and you're just like, "Goddamn! I'm trying so hard, and you broke my heart, and I'm hurting so badly right now, in a really beautiful way."

Bruce: The references people are bringing up are making me think of my pick for the most timeless protest song: "Oh Bondage, Up Yours!" by X-Ray Spex. It isn't pinned to a specific cultural moment -- it's addressing any sort of oppression and restriction, which I think is so cool.

Hopkins: Priests, speaking of restriction, it must be less restrictive running your own label, Sister Polygon.

Daniele: This leapfrogs off the whole purity conversation. Even though we're trying to grab more control over how our music is produced and distributed, we still have to partner with white men with capital, you know? [Laughs.] The whole idea of being an island is so false, but that's not a bad thing. We are all interdependent. When I hear someone say, "I've done it all myself," I'm like, Shut the fuck up. No, you haven't. Who ran the show space for your first show? Who played with you? Who was the first person to tell you they loved your band and make you want to keep doing it?

Greer: With Sister Polygon we're building a cultural landscape that makes more sense to us. We have so many artists making music that I want to hear and that I think other people would want to hear, but that the market doesn't necessarily make room for. We need places for these things to exist and grow so that we're not just hearing Ed Sheeran on the radio.

Hopkins: Yes. I'm using this interview as a platform to challenge the Chainsmokers to an arm-wrestling contest in Times Square. No, I'm challenging them to a Golden Girls trivia contest.

Photography: Daniel Seung Lee

Styling: Derek Nguyen

Prop Styling: Greg Garry

Hair & Makeup: Angela DiCarlo