The elevator doors open to the fourth floor of World of Wonder studios. I'm half an hour early, but RuPaul is already there, in his plaid coral-and-aqua Mr. Turk suit, engrossed with his iPad. A part of me wants to scurry back into the elevator--the domineering image of Mama Ru from nine seasons of his titular Drag Race writ large on my imagination--but finding the appropriate nerve, I introduce myself, extending a hand in greeting. He shakes it for a second, before letting his shoulders collapse in disappointment.

"You gotta give it to me harder than that."

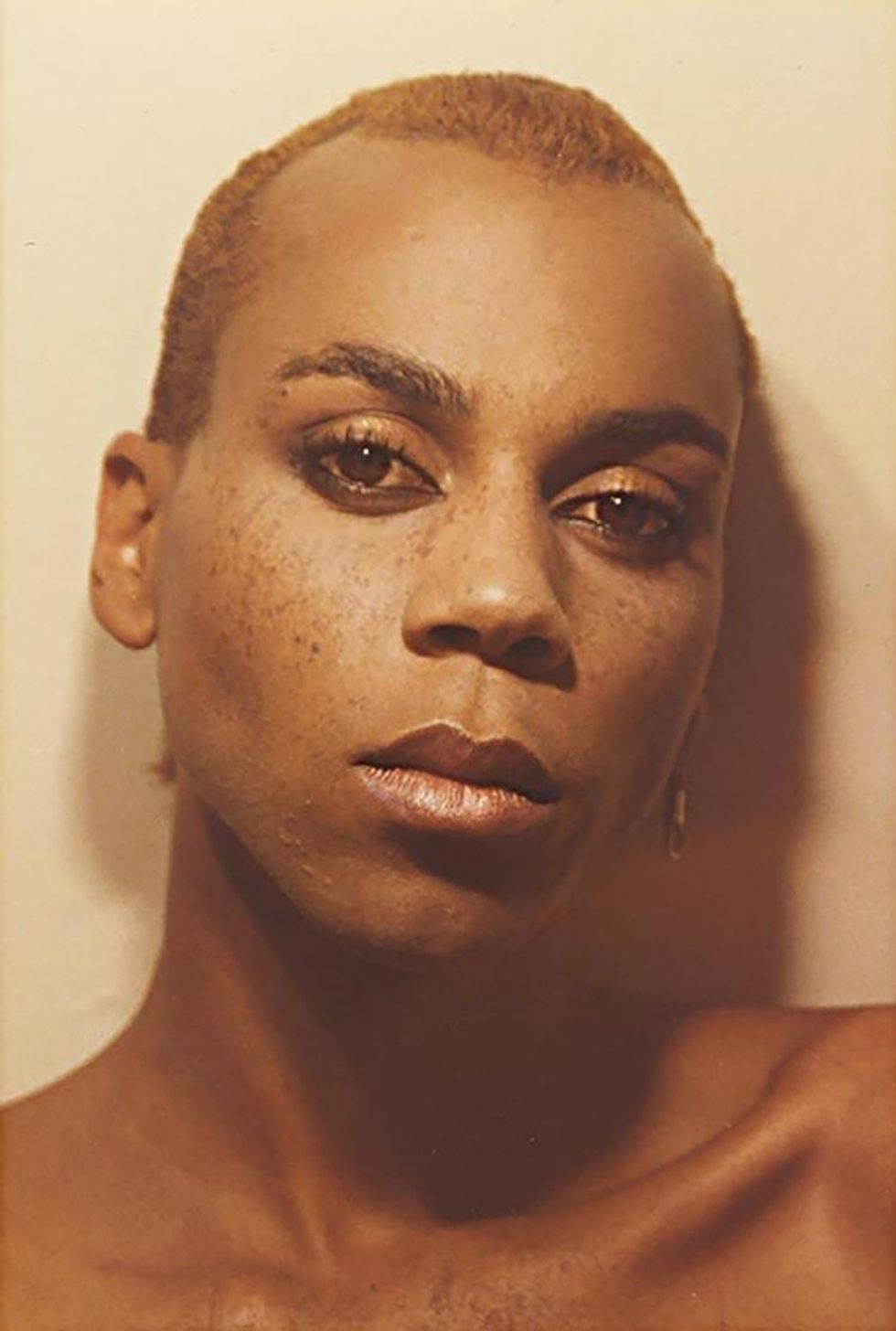

My handshake, it seems, is not firm enough. RuPaul then lectures me on the importance of a strong handshake and looking the other person squarely in the eye. If he had told me to lip-sync...for my life...right then and there, I would have. That's the authority on which all 6 feet 4 inches of RuPaul stands--a hard-won authority, born of an acute, almost innate self-awareness and the payment of many a due, with receipts at the ready. If there's anyone who can speak, authoritatively, to the past quarter-century of queer history and visibility, it's RuPaul Andre Charles.

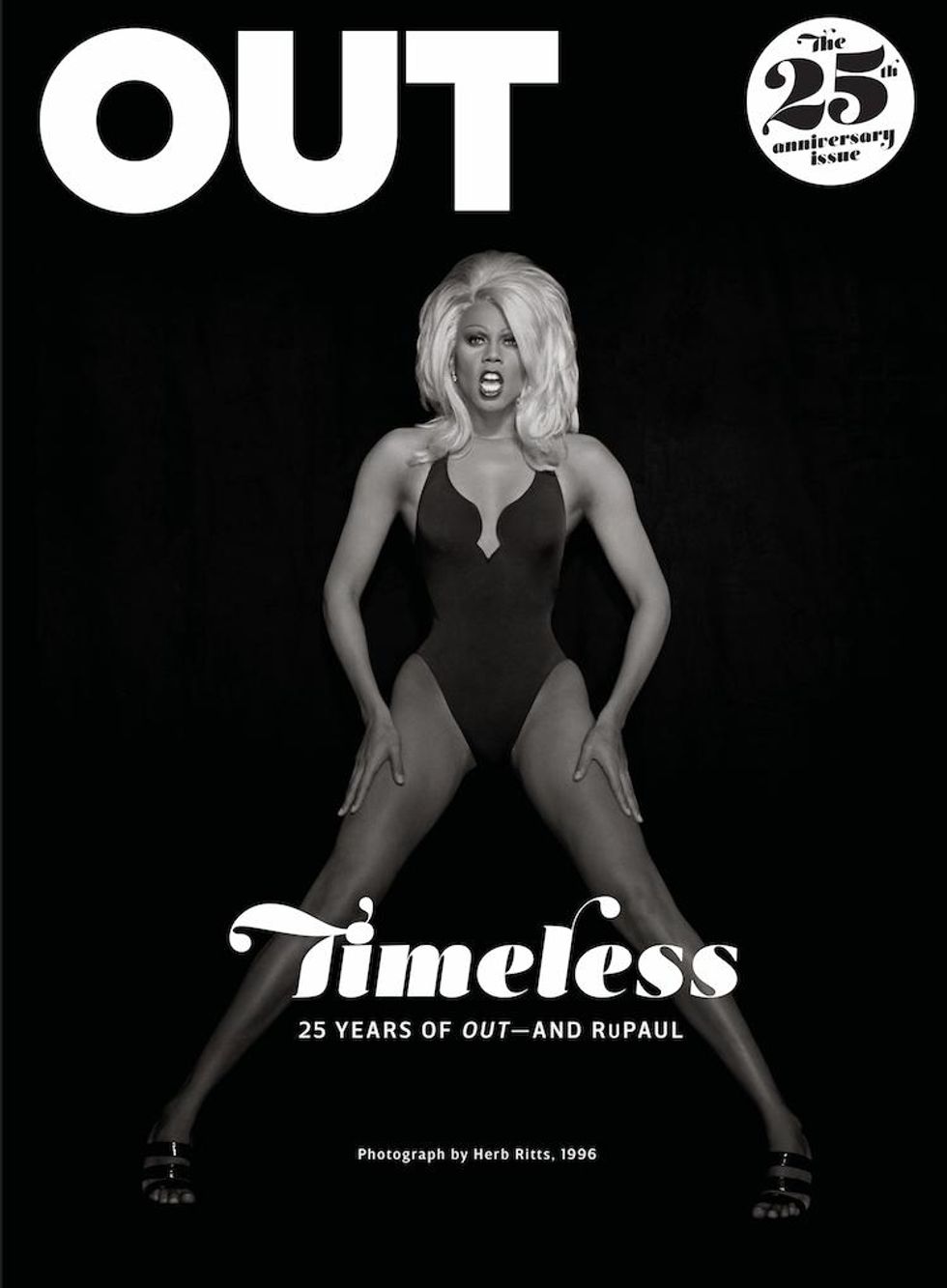

The first issue of Out hit stands in October of 1992. A month later, "Supermodel (You Better Work)" shanted its way onto the airwaves. Not one to rest on a hot iron ripe for the striking, RuPaul parlayed the success of his infectious dance song and its subsequent video into a career as the Drag Queen of All Media: hosting a radio show for New York's WKTU, publishing his memoir Lettin It All Hang Out, launching a talk show for VH1, and appearing in films like To Wong Foo, The Brady Bunch Movie, and But I'm a Cheerleader. Though his success was sudden and meteoric, it was more than a decade in the making, the result of a concerted effort between Charles and Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato, his longtime friends and collaborators.

Related | Gallery: 25 Years of RuPaul

After meeting in film school at NYU, Bailey and Barbato founded World of Wonder as a record label for their '80s synth-pop duo, The Fabulous Pop Tarts. But in RuPaul they met a kindred spirit--a kindred spirit in a Mohawk and jockstrap, with a shared affinity for Andy Warhol and the prescient knowledge to plaster posters of himself around town with a simple declaration: "RuPaul Is Everything."

"Drag has always been a tool for me," RuPaul says. "I realized early on that it worked really well to get the audience to react. I knew there was power in drag, like the Superman costume to my Clark Kent. Actually, when I met with J.J. Abrams about the show that we're doing [based on RuPaul's life], the whole pitch was explained to him and he said, 'You know what? I got it! It's the origins of a clan of superheroes.' "

Here, super friends RuPaul, Bailey, and Barbato reflect on the past 25 years of queer pop culture and where it's all headed.

RuPaul: Fenton, I met you on a Sunday afternoon in 1984 at the Pyramid in New York. You had come to listen to, I think, [The Fabulous Pop Tarts song] "New York City Beat" on the sound system.

Randy Barbato: You're kidding! Oh my God!

Ru: Then I met Randy in 1985 at the New Music Seminar at the Marriott Marquis in Times Square.

RB: And what were you wearing then?

Fenton Bailey: I remember.

Ru: I don't. There were so many different looks... It was probably a jungle story line: a Mohawk and a jockstrap...

FB: But it was with shoulder pads with the shredded thin liners, like from the sides.

RB: And you had a Wee Wee Pole record.

Ru: Yes, the record from my band Wee Wee Pole, 'cause New Music Seminar was indie groups and indie labels converging to schmooze and network.

RB: And so there were a lot of like-minded people coming together around music, but you were doing genderfuck. You've always been punk drag.

Ru: Yeah, it's a revolt to the status quo, not only the hierarchy of sexual concepts in the straight world, but really in the gay world, because boys like me didn't fit into any of the categories available. So drag was definitely a way to say, "F you, I'm gonna do my own thing."

FB: Well, that's the thing. It was really about leaping over everything, cutting through the noise and the clutter--the idea that you'd walk into this massive atrium at this hotel and your eye would just go to one place: you in the thigh-high boots and the shoulder pads. It really was, above all else, attention-shifting.

RB: The weird irony of all that, which we learned as we came to know you, is that even though it was stereotype-bashing, gender-bashing, and attention-getting, for someone who could attract so much attention, you're kind of quiet, unassuming. A loner almost. Is that fair?

Ru: It is fair. I think everybody has both. I always felt like a quiet kid, but I knew that I had a destiny to be in front of people--whether it was my mother telling me I was gonna be famous, as per the psychic she had seen when she was pregnant with me, or just the other kids in the neighborhood. I was always singled out. I could never blend in--never. Even in my family, I was the only boy, so there was them and then there was me. I like being alone and doing my own thing, but this is my destiny, you know? Being out in front. So I said, "OK. I'll do it."

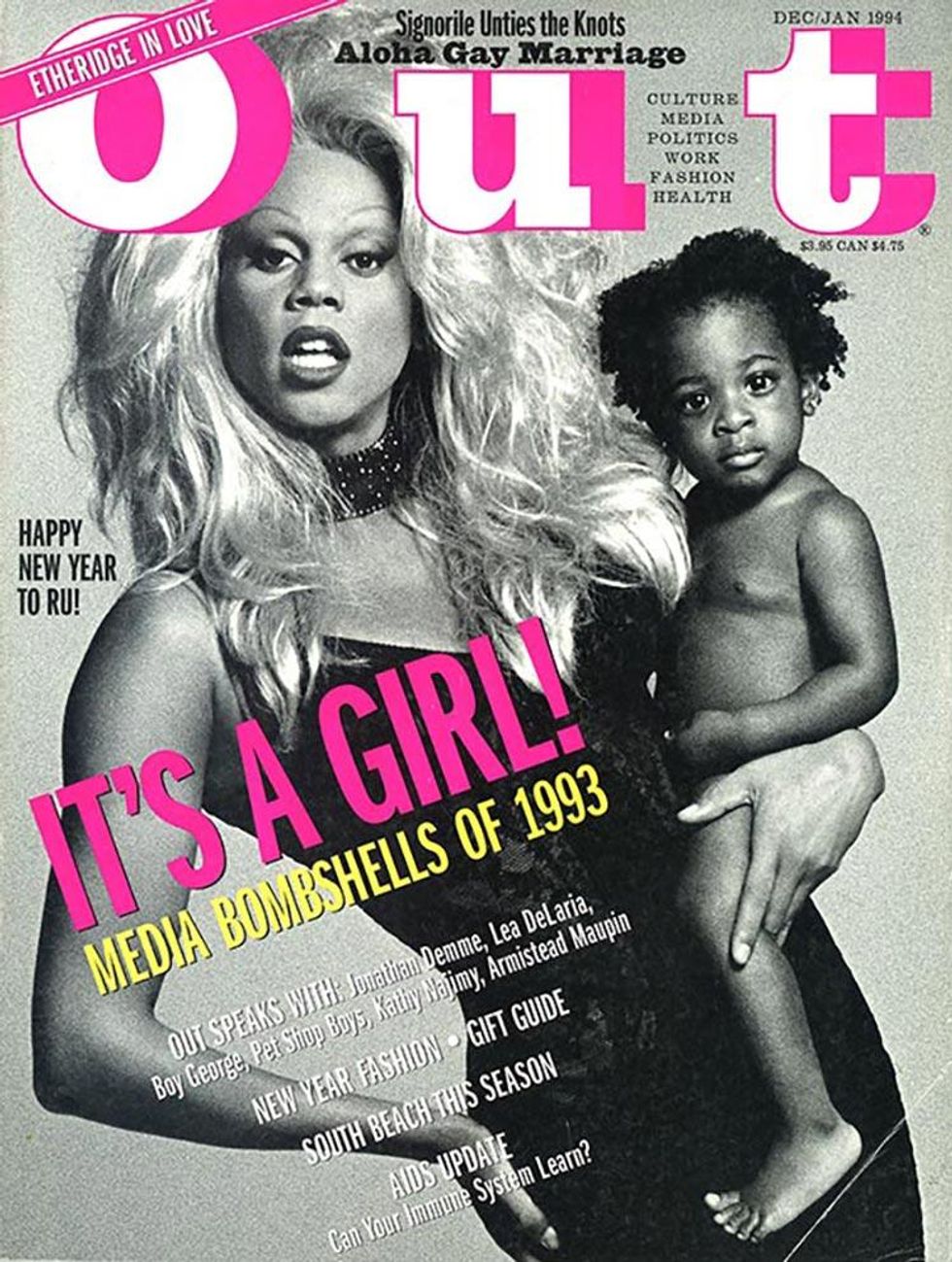

RuPaul on the cover of Out, December 1993 (Photograph by Francesco Scavullo)

RB: I think you were also such an observer, and you took being on the other side of the screen [seriously], whether it was watching Diana Ross or Merv Griffin. As a real student of pop culture, you can tap into that and tap into the audience's collective consciousness.

Ru: Politicians do it all the time. Even with what's happened with the trans ban in the military, it's a classic distraction technique away from all the losses within health care. It's a way to pull the hoi polloi, Betty and Joe Beercan, back to support you, because that plays to their fear and superstitions. That's what's happened with my career, and that's why it's so important to have people who you trust, who you can bounce ideas off of, who understand the template you're working with. That's why we've worked so well together.

RB: And we've never had to edit ourselves around each other. Everything we did, even back then, we weren't really thinking of it in a gay, activist, political way... Our essence was activism in a way, right?

Ru: Exactly. It's the bohemian creed. It was less about being in the closet or out of the closet; it was more about beauty and love and openness and colors and music and joy and expression. And that definitely fits into the gay experience, but it's not necessarily a "gay" movement. There were LGBT people in our crowd, always, but back then in New York, it was uptown, downtown, black, white, gay, straight, everybody.

RB: And we respected our differences. Not even like an earnest, Oh, I'm gonna respect you 'cause you're.... It was organic.

Ru: We were devotees of the Warhol doctrine. We grew up reading about Andy Warhol in Interview magazine, and about all the kids who came to New York, changed their names, and became downtown Warhol superstars. That was the template we had all subscribed to. And as an observer, I knew the steps of what to do in show business. Before I got into drag, it felt like I was a blurry image to people, but once I got into drag, people let me know, Oh, now I see you. The following year, after I met you two, you produced my album, RuPaul Is: Starbooty! That was '86, and then fast-forward to '91, I was ready to make that leap from downtown star to, you know, mainstream star [laughs], and so you began to manage my career.

RB: The idea of us managing you? Ru, you managed us. You were like, Do you want to do this? Here are the things. You had a list. Even when it came down to the "Supermodel" video, yes, we got to direct it, but there was clarity and it really worked. Even pre-sober, which was Starbooty, you were very focused and knew what you wanted to do.

Ru: Well, my goal was always Hollywood and mainstream stardom. I say "mainstream" just as a term, because mainstream is kind of deceptive. But you know, in those years between meeting at the Seminar and '91, when I was finally ready to do it, I got a little sidetracked from time to time. Deee-Lite blew up overnight, and they were kids from our neighborhood. We were all friends. I thought, Wait a minute, weren't they behind me in line? And I realized, Oh, bitch, you took a little nap in the poppy fields like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. And I had to wake my ass up and say, "Let's get at it."

FB: I remember sometimes feeling frustrated because we sent your demo to every single record company. Every single one, except one, said no. But of course you only need one to say yes.

RB: The record company that chose us was a hip-hop label.

Ru: That, by the way, had organized the New Music Seminar. Tommy Silverman, who's Tommy Boy, owned the New Music Seminar, where we all met. And then "Supermodel" came about because I'd started doing drag as a social commentary on synthetic identity. As I was evolving in New York--rent's gotta get paid and grandma needs a new car!--I started doing my more sexualized drag, more like a Soul Train dancer: short skirts, shaved legs. I actually put on a bra with rolled-up socks in the cups to emulate real titties. And that's when I started really making money, because people were like, Bitch, you are fucking sexy! Straight men would give me money on the go-go box. In '89 I was crowned the Queen of Manhattan, which was a big thing back then. Publicists and promoters and columnists voted on who was the "it" drag queen and the "it" drag king. So that was the pinnacle of downtown success for us in the club world. When my tenure was over in 1990, that's when--

RB: It was time to go from high school to college. It was like, you were the prom queen, and there was no place else to go.

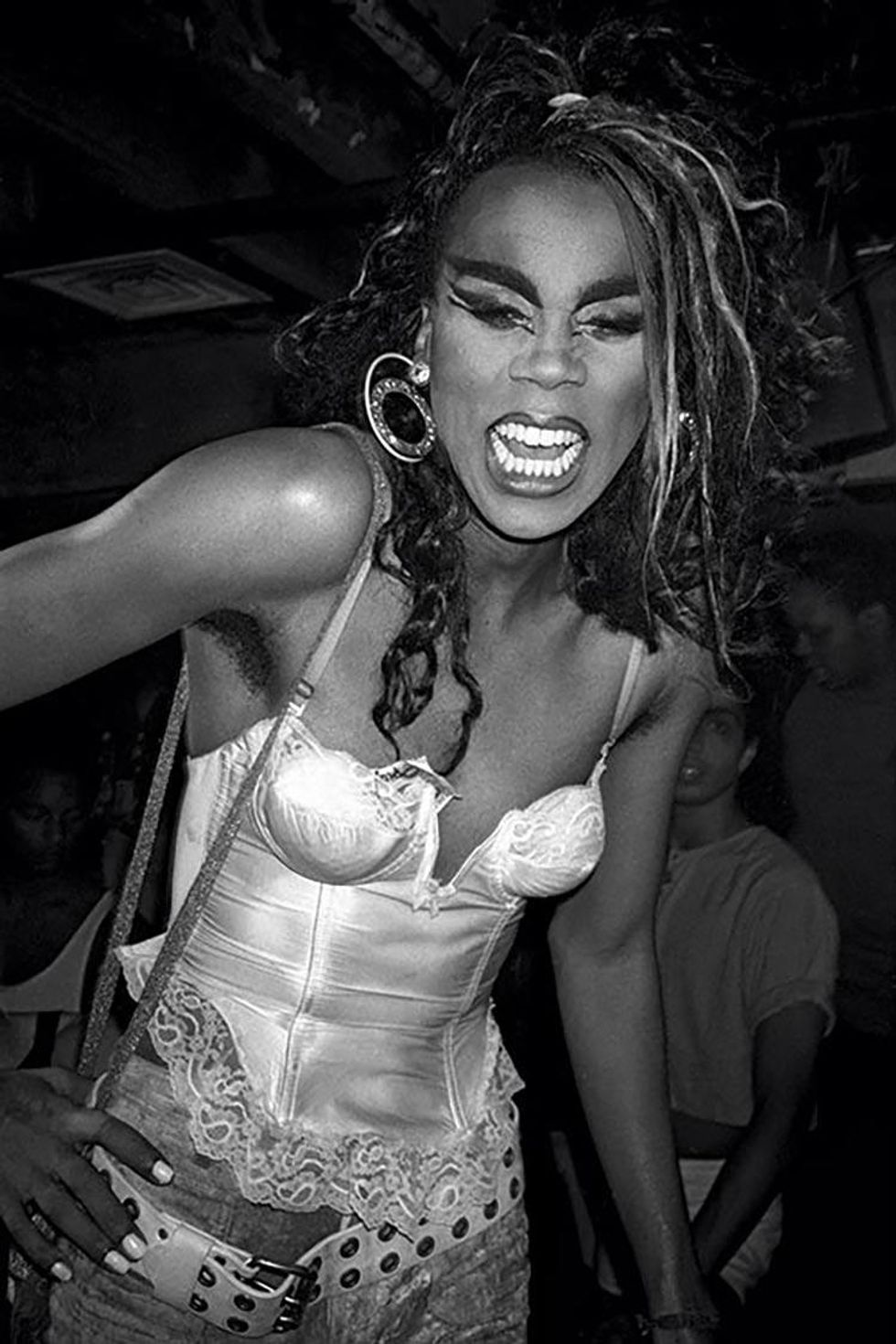

RuPaul in Manhattan's Tunnel, 1988 (Photograph by Patrick McMullan)

Ru: I stopped doing clubs. I contacted my friends and started working on a demo tape. When we got the contract for Tommy Boy, my old friend Larry Tee told me I'd been sort of working a high glam look and said, "You know, I've got an idea for a song: 'Supermodel.'" And he had written down some lyrics, a few phrases, and my music collaborator Jimmy Harry and I took what he wrote and added to that, and that became the song "Supermodel (You Better Work)."

RB: It's funny because the video is not dissimilar to so many things today, like the whole DIY approach of it. We interviewed a bunch of different directors, the budget was going to be 10 cents, and then we were all just like, Wait, we should just do this video, because that was going to be how we got the most on the screen. Ru was very clear: "Mahogany!"

Ru: Before my mother died I got to visit her, and she saw an interview on MTV that I'd done with Kurt Loder. She looked up, like, Oh my God, and said, "Nigga, you crazy." That was confirmation that she knew what my birthright was. Obviously it could have been all ridiculousness that a psychic told her I was going to be famous. But I believed it. There were times when I had my doubts, during those lean times, but "Supermodel" was like, OK, this is it.

FB: I always get struck by the story when your mom left. Because it seems to me she just felt like, My work is done, mission accomplished.

Ru: That's right, because I was performing at the Gay and Lesbian March on Washington and I was on stage. They announced my name, the sun was setting, there were these dust clouds because people were rushing to the stage, and I had never experienced that before. As I'm on stage I see a plane taking off at Dulles International Airport--I knew that my mother was ill--and in that moment, in that split second, I saw the plane and the sun setting, orange because of all the dust in the air, and I was like, Oh, my mother, my mother is taking off. It's a split second that stays in my mind. When I got home, Randy called me, and as soon he told me that my sister called, I knew exactly what that meant. That Toni--my mother--that was it. And yes, her work was done.

FB: One of the first times we saw you was out in the street wheat-pasting posters in Atlanta with "RuPaul Is Everything," which, to me, was the mission statement. It was a list of all these things that Ru had, but it was really important to do that list because it wasn't about being a pop star with a record, or about sticking in your lane. It was very important for you to have the book, to have the cosmetics deal, to have the talk show--all those things.

Ru: After the success of "Supermodel," VH1 asked me to present an award at their first fashion awards. The writers wrote something for me, but it was the old drag-queen shtick, very bitchy. I do sassy--I don't do bitchy--so I rewrote the intro that they had, and it was a hit. In fact, I remember looking at all these people and they are laughing--all my idols: There's David Bowie! And there's Tina Turner! There's Iman! And I could see Madonna right there, not reacting at all, by the way. She's not even looking at me. And all of the people with her, her stylists and hairstylists, are seated all around her like a cocoon. They're following her lead and just looking forward, not laughing. After that, VH1 contacted us and offered me a talk show. We did 100 episodes, and it was so much fun. At the time I was doing a morning-drive radio show, promoting a book, promoting an album, and promoting MAC cosmetics, and I asked my co-host on the radio to join us on the TV show: Michelle Visage. Talk about finding people! To find someone who you have chemistry with and who you can banter with in a way that you don't even need guests? [Laughs] She's one of these hidden treasures I've found along the way, like, Who are you? What are you doing?

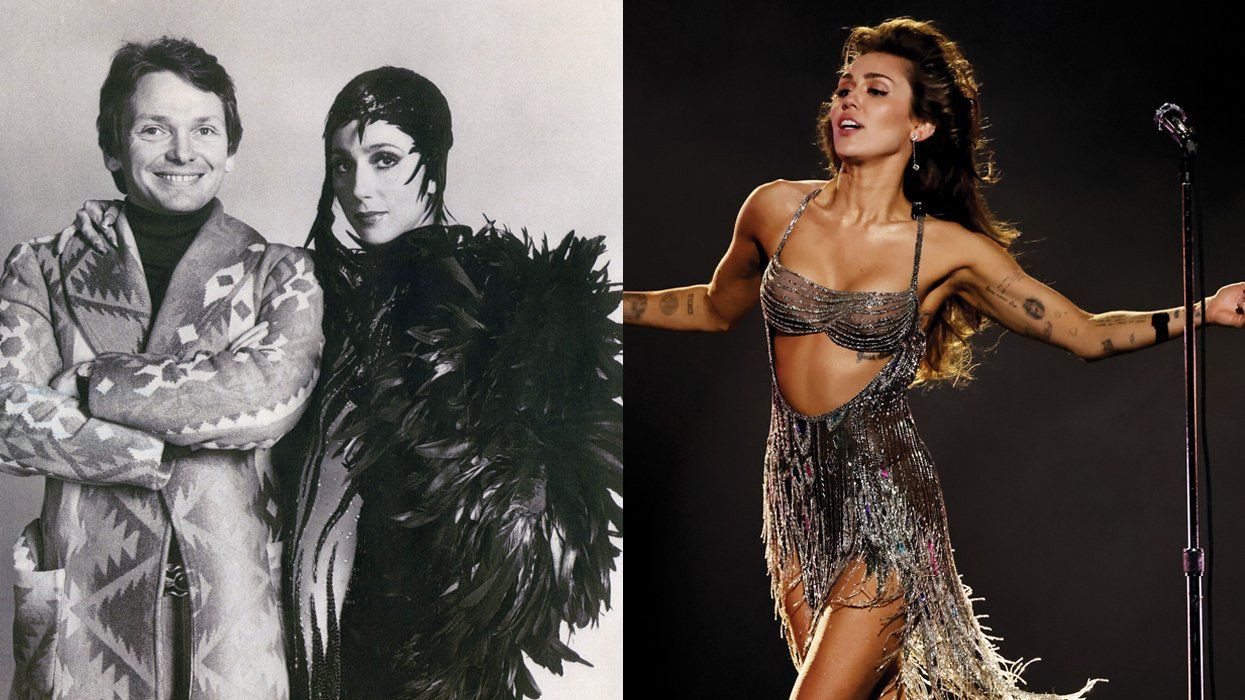

RB: And the bookings were phenomenal. La Toya Jackson, Tammy Faye Bakker, Diana Ross, Cher--

FB: Backstreet Boys, *NSYNC--

Ru: Bea Arthur. The first guest was actually Diana Ross. I met her in Paris in the waiting area for the Concorde. I was working there for MAC [Viva Glam], and I had to come back to New York to be in the movie To Wong Foo, so the MAC people got me a ticket on the Concorde.

FB: It's so Mahogany.

Ru: It's so Mahogany. And I heard her distinctive voice before I saw her: "I need to be in seat A1 because blah blah blah blah blah." I froze. I knew one day I'd meet her, so I thought to myself, Ru, stay calm, cool, collected, and come from your heart. So I walked over and said, "Hi, Ms. Ross, I'm RuPaul." She said, "Oh, hey!" She was really lovely and we talked and I said, "OK, I'm not going to bother you. I'm going to let you do your thing." And she said, "No, come sit down!" So as we sat down [former Clinton adviser and civil rights activist] Vernon Jordan came over and said, "Hey, Diana," and she said, "Ru, do you know Vernon Jordan?" I said, "Hello, pleasure to meet you. I should let you guys-- ." She said, "No, sit down." And she finished with him, and then right after that Robert De Niro came by and said, "Hey, Diana, how are you?" And she goes, "I'm fine. Bobby, do you know RuPaul?" And he said, "Yes, I do know RuPaul," because I had met him a few months earlier at a Luther Vandross concert. We sat there and talked and it was lovely and then it was time to board the plane. So then when I got on the plane, she was in seat A1. After we got up to 100,000 feet in the air, I got up to use the restroom in the front of the plane, so I had to pass her in seat A1. As I got to her, there was a line. She said, "Well, Ru, I'm after you." I said, "OK, all right." So I got in the bathroom. It was a mess--nasty, horrible. So I thought, I gotta clean this up, because I wasn't gonna let her think that I was the one who did this. So after I used the restroom I wiped things down and cleaned it up because she was gonna come in after me. [Laughs] So anyway, yeah, she was actually the first guest on the VH1 show.

RB: It was magical, when you think about it, and so ahead of its time.

Ru: Throughout history there are windows of clarity, windows of opportunity--the '90s was one of those times. Clinton was in office, there was an openness happening, and then the pendulum swung the other direction with Bush. We're witnessing that now. But it's different with this Trump administration because it's not that the openness and forward thinking has diminished--actually, the forward thinking is bigger than ever. It's that the other side feels more threatened than ever before, so they've rallied around this fool and this concept of trying to turn the clock back, which has never worked. It feels like the stakes are higher for both sides.

RB: Also, the stakes are higher because it's not just political ideology. It's disguised as political ideology, but the reality is, it is the last gasp of the old-white-male hierarchy, and Trump is at the helm. But Trump's motivations are purely selfish. He's just an evil person, so that's where I think it's unlike anything we've experienced in our lifetime.

Ru: During Bush, I retreated. I retreated and I moved away. I stepped away from the canvas, and in hindsight I realize that was the smartest thing I could have done. Because I recalibrated my mission statement. Lots of therapy and sobriety showed me that I'd been motivated so much by my father and getting his approval, and then I had to change that. And so when I did come back, my mission statement really had to be about what I love about life, which is the music and the laughter and the colors and the creativity and the problem-solving. At this very table, we sit and brainstorm these ideas and it is the most exhilarating thing I've experienced in my whole life. I still worked during that time, but I didn't have the ambition, I wasn't driven--I just paid the mortgage.

RB: Was that your second wave of sobriety? Because you stopped drinking and then you stopped smoking pot. I remember when we were doing the talk show, it hadn't happened. The pot was still--

Ru: Right, so in '91 when I started working with you guys, I quit doing chemicals [laughs], and I stopped drinking, but I still smoked pot. And then when I met [my partner] Georges [LeBar] in '94, I decided to quit smoking and then slowly stopped smoking weed. I eased back into weed a little bit, as the workload got stronger--I mean, I needed a little something that was stronger than coffee! So I started smoking weed a lot more, and that was when we were at VH1. And then in '99 I cut out everything.

RB: I only bring that up because I think that was an important part of your journey during the Bush years: the retreating, recharging the battery. There was a new level of self-awareness.

FB: But I also think the audience had to change in the sense that a big, black drag queen with blonde hair emerges--and it's amazing and exciting--but there was always that thing of like, Oh, but it's a drag queen, there's nothing more there. The audience needed to get beyond that moment. That was the point of entry, but I also oftentimes felt like people just didn't get where it was really coming from, and weren't ready to understand that idea. It was another thing to really grapple with it as more than a gimmick and a novelty. So you needed to let it all sink in for a few years.

Ru: Kick around for a couple of decades. And also, the audience did change, because young people who watch our show who don't have all the baggage from the 20th century are able to get it faster than the generation before. They're able to get the duality and the nonbinary stuff--

FB: Without your having to explain--

Ru: Exactly. They understand the importance of it, so that's a testament to sticking around long enough for your number to come up again. The mission for Drag Race was to celebrate the art of drag and, in doing so, humanize and put a face and an emotion and a political viewpoint behind it. So first drag as an art form, that's number one. And then it's about informing people of the courage it takes to excel and become fully realized as a drag queen in a male-dominated society. It is the most punk-rock thing you can do in a culture that fetishizes masculinity. And then you get the inside stories: What kind of person does this, who's behind it? That is a person who's been through fucking hell and high water. They have been ostracized and kicked out of their family. They've acknowledged what society wants of them, and they've said, "You know what? I'm not going to do that." So all of those elements inspire the viewer. The show at its core is about the tenacity of the human spirit. Same as Paris Is Burning, when you see these people who have been through horrible situations, and then they get on that floor and they bloom. And it's beautiful. It's tragic when you look from afar, but when you look closely you go, Oh my God, it's incredible.

RB: And the fact that so many of them come from the show and launch these enduring careers, it's really an anomaly in terms of TV shows. We're going into the 10th season. A lot of people who make this show have been on board since season one. When you watch it, you can tell the level of passion behind the screen is the same level of passion as the artists on the screen. That's unique.

Ru: They had come to me with reality shows for many years, but I didn't want to do it before because I saw reality shows as mean-spirited, but something had changed.

RB: And Tom Campbell, who's sort of an EP and a creative voice of the show, was a pit bull about it.

FB: Because I remember saying, "We tried that, it's never gonna sell." But I think Ru said, "I'll do anything but a competition and elimination show." [Laughs]

Ru: Probably.

FB: Then we pitched him all these ideas and he's like, You know what we need to do? We need to do a competition show.

Ru: Things had changed, not because of Obama--but Obama was part of this shift, those windows of opportunity--and I could feel it and I knew it. We took it to, I think, five different networks, and Logo pretty much bought it in the room.

RB: They have been awesome partners. Even for Chris McCarthy to make the decision in the ninth season to take it from Logo to VH1--that was a pretty smart choice. And they have let the show grow.

Ru: Part of our job as the elders of the movement, so to speak, is to curate things that are important for the young people to know. There were people in our lives, Dick Richards and Nelson Sullivan, who videotaped all that footage of us that you see on YouTube, who taught us about Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Tallulah Bankhead, Fellini films.... So to pass that along on our show is a way for us to keep the dream alive.

RB: Even in booking Debbie Harry or the B-52s--the new generation doesn't necessarily know [who they are]. We aren't PBS, but we do have a responsibility to educate the children.

Ru: At DragCon we get to see all these 13-year-old kids who are gay, straight, nonbinary, whatever, and they are the hope for the future. They don't have the baggage that people from our generation--or even the generations right before theirs--had. That's the revolution right there. These kids have their parents bring them to this event, and those parents are my age and younger even. Because all of our girls are so courageous, and they've been through so much--you see it on the show--these parents are smart enough to want their kids to learn these same tools to navigate life. Not just what's happening outside of you but what's happening inside of you. And I think that's where the revolution is. It's an inside job. And it's not just about gay people, it's about taking mankind to the next level. This whole election felt like we took this wrong turn and circled around to the exact same place we've been before. But ultimately, that will propel this conversation forward. That will wake up these kids who've been looking at their smartphones all this time and they'll say, "You know what? I gotta get involved with this." Our show has been a touchstone for this sort of forward thinking, for people who have that yearning inside to take the human story line to that next ring of evolution.