For an actor, Prior Walter might be one of the most daunting characters ever written. He's the consummately tormented, AIDS-afflicted gay man at the center of Angels in America, a 1980s-set, two-part, seven-plus-hour play that covers political, spiritual, sexual, medical, and metaphysical ground while swirling around the plights of its lead.

Related | Andrew Garfield is Among the Angels For His Broadway Return

"On some terrible level, theater has never progressed past its origin as a blood sport -- as a sacrificial ritual," says Tony Kushner, Angels' lauded playwright. "Somebody is getting cut open on the altar for the rest of us to sit safely and partake. In different ways, all eight of the characters in Angels do that, but Prior probably does it more than any other character. And you want an actor who's going to go hell-for-leather--somebody who will be unsparing. The audience wants it, needs it, and appreciates it."

Andrew Garfield, who played Prior in last summer's National Theatre production of Angels, and reprises the role on Broadway this spring, was shaken by the task. His first exposure to Kushner's opus was the 2003 HBO miniseries adaptation, starring Meryl Streep and Al Pacino, and directed by Mike Nichols. Garfield was studying at London's Central School of Speech and Drama at the time.

"Me and my [college] friends wore out the DVD," the actor says when we meet in New York. "It was a master class in acting, writing, performing, directing -- the whole deal. There were six of us who would crowd around the TV and try to drink in what was happening, because, as far as actors studying, it was perfect."

That memory prompted Garfield to immediately accept the part when asked by director Marianne Elliott and Kushner, whom he'd met while playing Biff in Broadway's 2012 run of Death of a Salesman (also directed by Nichols). But then Garfield read the material.

"I said yes because I remembered that body feeling I got from the film, and I knew it was important," he says. "I'm usually very diligent with my decision-making, but I'd never actually read it. When I did, I was like, Holy fucking shit -- how?! How is anyone supposed to do this?! It's a question for any actor who plays any of the parts in Angels, but especially with Prior -- he's dealing with the divine. How do you begin to feel like, Oh yeah, I can figure out dealing with the divine?"

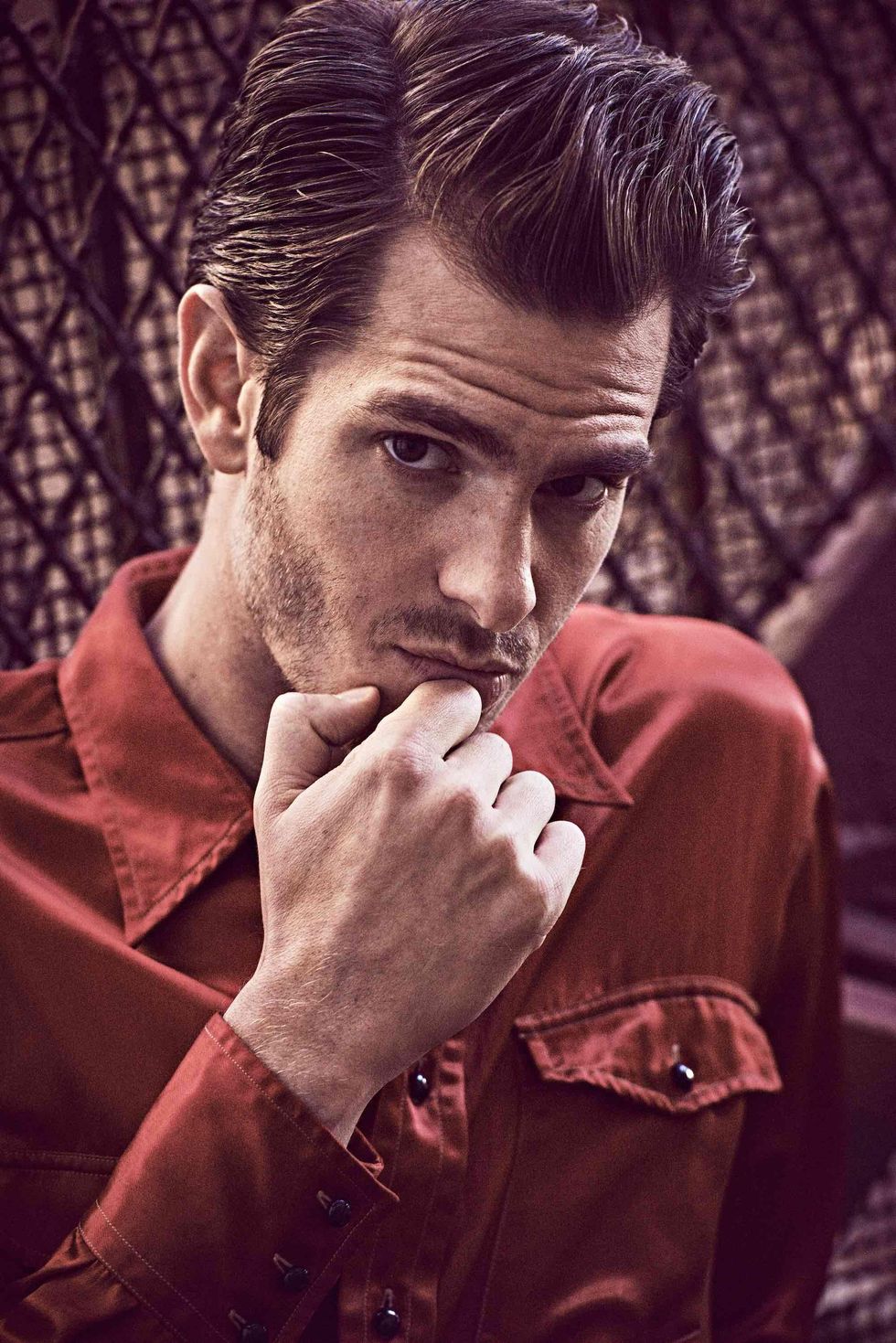

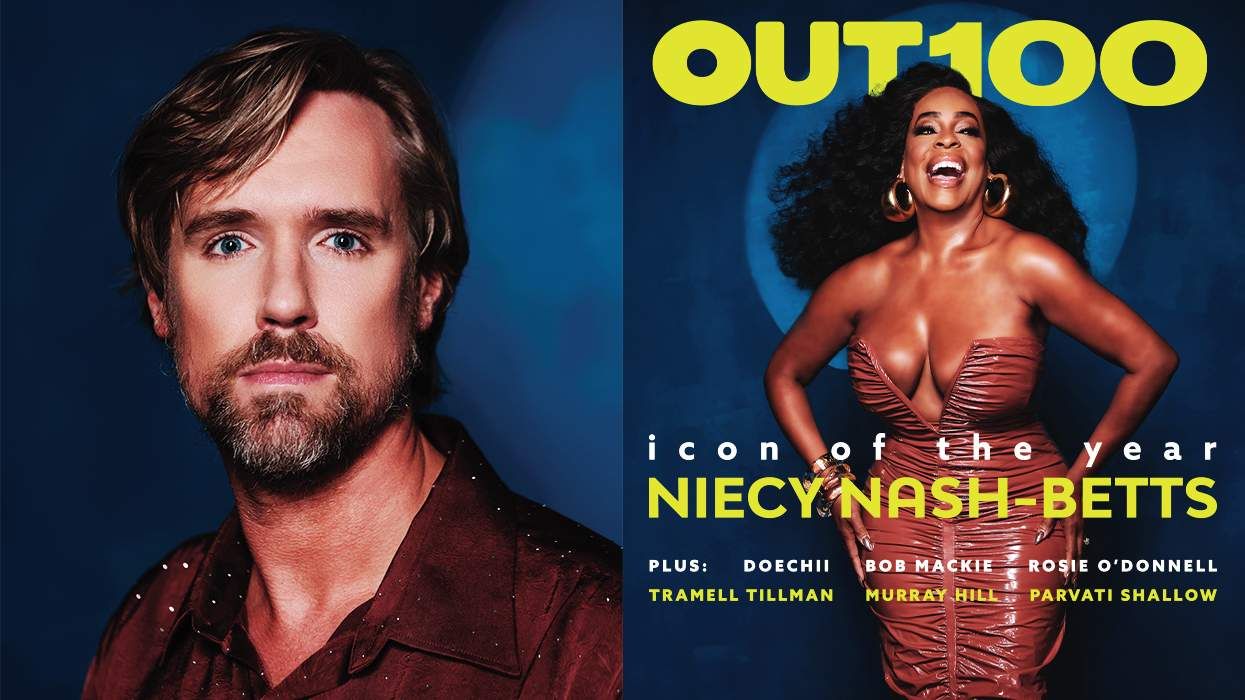

Shirt by Gucci. (Photography: Matthew Brookes)

Unlike Prior, Garfield may not be literally burdened by the heavens -- enlisted as a prophet by a hermaphroditic angel as he desperately clings to life -- but he does have the look and aura of a man who's both hopeful and feeling the world's weight. Between the U.K. run (which ended last August) and the Broadway revival (which opens in previews February 23), he's let his beard grow in a bit; his beanie, puffy coat, and skinny jeans add to his air of a millennial Moses. His speech and demeanor support the persona: He seems wide-minded, humbled by the universe, and philosophical to a fault. And despite all the theatrical demands of playing one of the most iconic queer characters in history, what plagued the Oscar-, BAFTA-, Golden Globe-, and Tony-nominated actor most was whether or not he was inherently qualified.

"Up until this point, I've only been sexually attracted to women," Garfield says. "My stance toward life, though, is that I always try to surrender to the mystery of not being in charge. I think most people -- we're intrinsically trying to control our experience here, and manage it, and put walls around what we are and who we are. I want to know as much of the garden as possible before I pass -- I have an openness to any impulses that may arise within me at any time. But, if I were to identify, I would identify as heterosexual, and being someone who identifies that way, and who's taking on this seminal role, my scariest thought was, Am I allowed to do this?"

Related | Andrew Garfield Comes Out as Gay 'Just Without the Physical Act'

Last July, Garfield was briefly hounded by the media for saying he was "a gay man...without the physical act." The quote, like many that are pounced on to either denounce celebrities or probe into their private lives, was taken out of context. It was plucked from a semi-public discussion involving the actor's preparation process in London, which included watching lots of RuPaul's Drag Race -- a warm-up for playing a character who practiced drag before falling ill. Beyond his general need for exploration, and his goal of plumbing the psyche of a wholly identifying gay man, Garfield says, "I think part of what I was trying to say was about inclusion, and about that openness to my impulses." (For the record, Garfield thinks Drag Race might be the best show he's ever seen on television.)

Since 1991, when Millennium Approaches, the first part of Angels, made its stage debut and went on to win a Pulitzer, a Tony for Best Play, and an embarrassment of additional honors, Kushner has seen dozens of actors play Prior across the world. He doesn't like to compare the performances, but he admired Garfield's willingness to be sacrificed, as it were, and he says there's a darkness in the actor's interpretation that's "a new color" for the playwright. And despite our current era of heightened identity politics, wherein straight and cis actors come under fire for stepping into queer parts, Kushner was never dismayed.

"Marianne and I both had Andrew at the top of our lists," he says. "And he was nervous, but I was certain that he wouldn't have any real difficulty making the imaginative, fantastic leap that he'd need to make. And we talked about certain aspects of it, but mostly, he did what he did on his own, and I was completely astounded. I think it's one of the most remarkable performances of a contemporary gay character by a straight guy I've ever seen. In the United States, at any rate, you sometimes see a kind of nervousness among straight actors playing gay: 'Am I making the character too queeny?'; 'Is this a stereotype?' There's a certain misunderstanding that queenly behavior has to do with a kind of abjectness or weakness. But, of course, the opposite is true. It's a gesture of real power. It is a refusal of hiding. Andrew and I had a lot of discussions about that, and I think that was the most important thing I could communicate. There's great joy in that kind of gay behavior -- great energy, great wit, and a great force of strength. There's nothing wimpy about behaving like Judy Garland or Katharine Hepburn. And Andrew really grasped that instantaneously and ran with it."

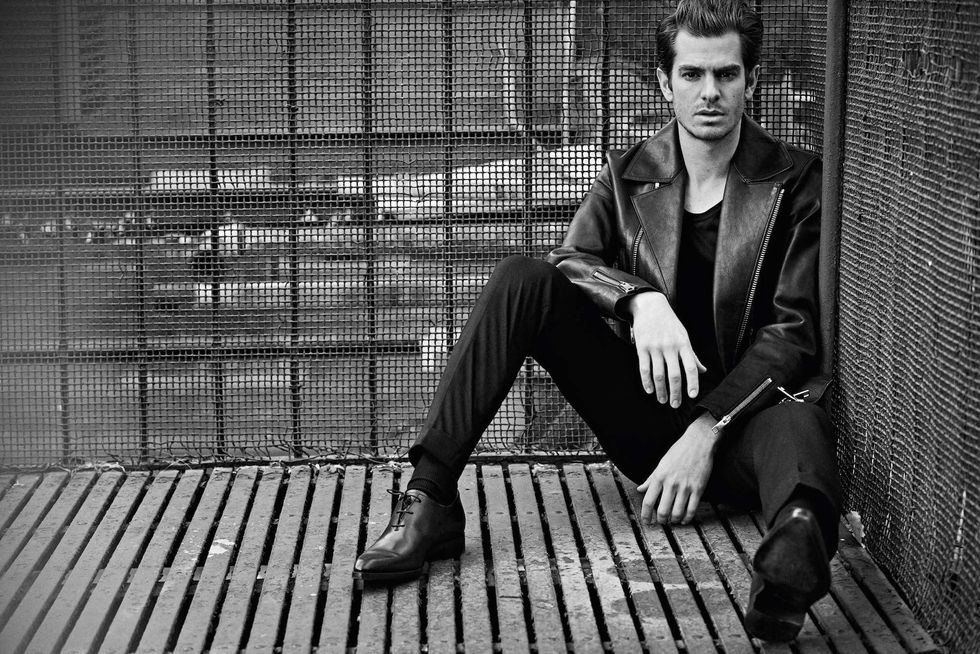

All clothing by Berluit. (Photography: Matthew Brookes)

"He certainly has all of the equipment to take on the role," adds Nathan Lane, who costars with Garfield as Roy Cohn, the real-life lawyer who succumbed to AIDS complications in 1986. "He's immensely talented. He has a real challenge in that he's at the center of this storm, and he still holds it all together. I was knocked out by that. And I don't think he was quite prepared for how funny it is. There's a lot of emotion and tragedy in Angels, but also a lot of humor. And that's what has brought people in, particularly in regard to the character of Prior. One of the most exciting things about performing at the National was that you sensed that a new generation of people was discovering the play. There were a lot of young people going to it. And I think Andrew really understood all of these layers when he started playing it for audiences."

Younger viewers may best know Garfield as a snarky web-slinger in The Amazing Spider-Man, or a jilted entrepreneur in The Social Network, but of the actor's roles, the one that might be closest to his own personality is Desmond Doss, the weapon-averse pacifist he portrayed in 2016's Hacksaw Ridge, which earned him a Best Actor Oscar nod. When we speak, Garfield conveys a startling wealth of compassion, as if he's chipped away at his ego in fear that it might minimize his experience of the world. The actor, whom Kushner calls "a spiritual explorer," repeatedly cites a slice of Mayan folklore, and while its name escapes him, its message about the hope for human decency doesn't.

"I'll sum it up -- I'll butcher it," Garfield says. "It's a creation myth, and it holds the idea that human beings were introduced into the natural world because there wasn't another species that could praise beauty, celebrate beauty consciously, or make art. The idea was that the Mayan god created humans in order to experience gratitude for the bounty, mystery, and miracle of existence. And I think that's something that Tony is getting at in his own way with Angels."

Garfield's words can sound earnest and heady, but they're all part of his effusive manifesto about wanting to put good into the world. The 34-year-old, who grew up in Surrey, a prosperous county that borders London, says that particular desire didn't blossom until he found acting, after an existential crisis in adolescence.

"When I was a teenager," he explains, "becoming more sentient and questioning everything, I was thinking, Well, if this is all there is, then I'm not interested. I thought nothing made sense, and there was no point to any of this. It felt like The Truman Show. I stopped playing sports. I had no interest in academia -- or anything, really. It was my mother who said, 'What about something creative?' A question that simple. And theater really helped open me up -- and continues to open me up -- to reality in all its complexity, diversity, uniqueness, and chaos. And that's what Angels is about. It's like a handbook on how to change, how to become who we're supposed to be, and how to live in reality rather than in a deluded state of denial. Only when the world is accepted, with all the darkness and possibility of darkness, do we get a true taste of the highest possibilities of what it is to be human."

In Garfield's favorite scene in Angels, which takes place in part two, Perestroika, Prior's estranged lover, Louis (played by James McArdle), and the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg (Susan Brown) say the Kaddish, a Jewish prayer of mourning, over Cohn's dead body. Rosenberg, another real-life figure, was wrongfully executed for treason on Cohn's corrupt watch, while Louis, a bewildered idealist, hates everything Cohn stood for. As such, the scene is one of brutally tough forgiveness -- of sympathy for the closeted gay devil. "It kills me every time," says Garfield, who was raised by a Jewish father, and is familiar with the power and gravity of the prayer.

Additionally, Cohn was once Donald Trump's lawyer, and that's just a tiny part of what makes this masterful critique of Reagan-Era horrors so stirringly relevant today.

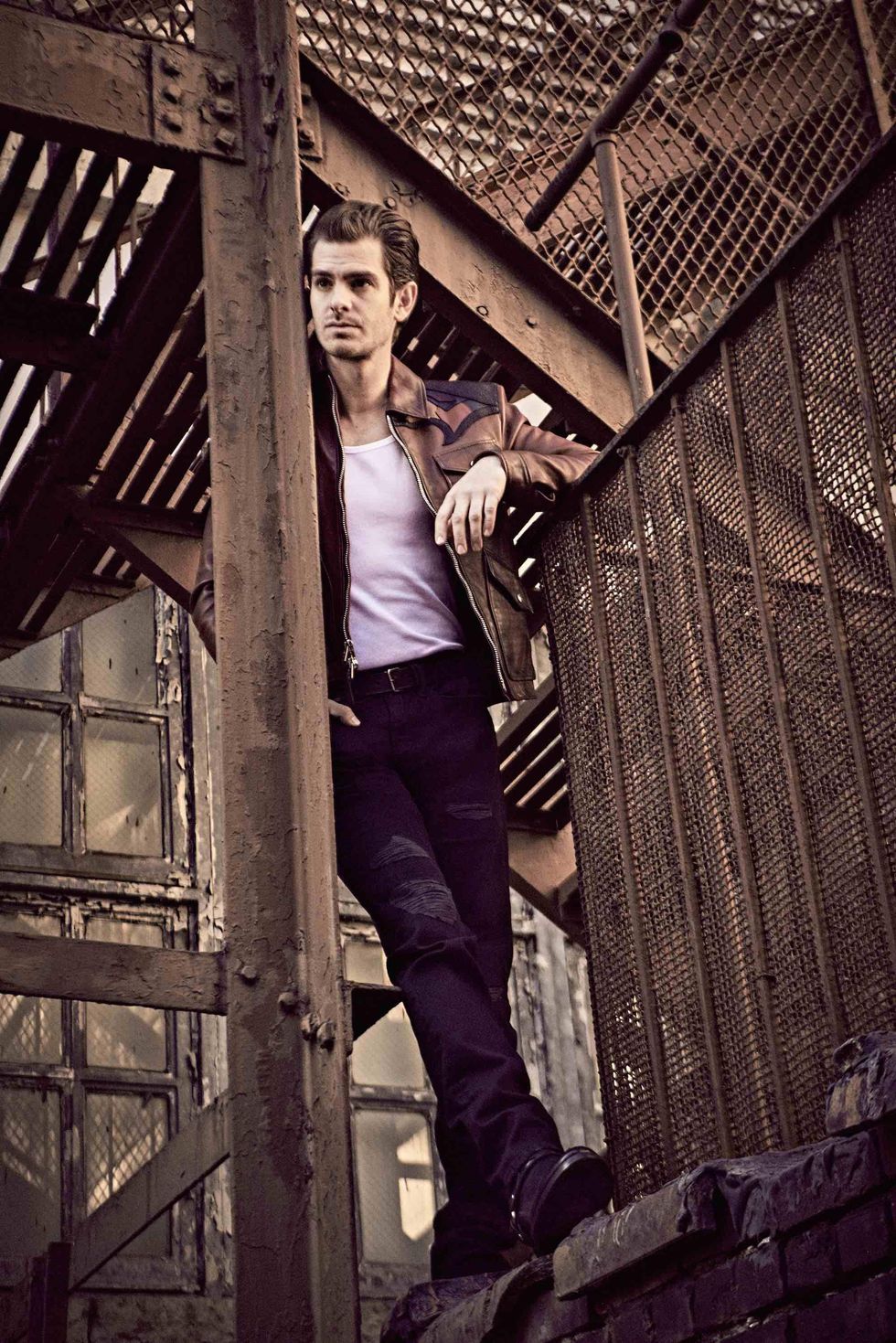

Tank top by Calvin Klein Underwear, Jeans by Frame Denim, Belt by Saint Laurent, Jacket and Boots by Coach. (Photography: Matthew Brookes)

"I wrote the play in part because I felt that Reaganism was doing staggering damage and posing a really terrible threat to American democracy and to the world," Kushner says. "And, unfortunately, I think I was right about that. But, as I've said many times, I think Roy Cohn was a much better person than Trump is. I still think he was a terrible person who did terrible things, but he did seem to have enough internal coherence for there to be a possibility of real, abiding loyalty to the people he loved. And I think he actually did love some people. He stuck by and defended Joe McCarthy even when it became unfashionable. Trump dumped Roy as soon as he found out he had AIDS. He's yelling now about how he wishes he had another lawyer like Roy, but when he found out Roy was sick, he pulled all of his business and they had almost no contact after that. On a daily basis, we're seeing that there is no place in Trump's shriveled, damaged soul for anything like object constancy or loyalty to take root. Except to himself. Everyone else is just food or a target."

And yet, in an extension of his profession of love for that Kaddish scene, Garfield finds himself grappling with his unyielding empathy for the human condition -- a topic of conversation he feels is crucial right now, what with, as he calls it, "the mass mob mentality and indiscriminate casting of stones" perpetuated by social media (which he doesn't use). It's hard times for anyone with faith in the restoration of decency, or, seen another way, in its long-awaited rise to the surface.

"How do you find compassion and love for the monsters we're living with?" Garfield asks. "How do you hate the disease and love the diseased? How do you hate the alcoholism and love the alcoholic? Maybe there are certain people who are born evil and are here to do evil deeds. Maybe there are sociopaths and psychopaths who are capable of those things and have no compassion. But in the cases of people like Roy Cohn and Donald Trump, I don't believe they were born evil. I believe, from my own pseudo-psychological standpoint, that they learned how to be -- learned how to survive. Trump somehow manages to survive with ugliness, and at all costs. But what this play is speaking to, down to the final monologue that Tony wrote for Prior, is not fire and brimstone. It's not 'we're going to kill the fuckers' or 'we're gonna cut their heads off.' It's incredibly gentle, loving, and compassionate, and it's confident in the natural propensity of the world and its benevolent forces to win."

Garfield and I are in Central Park, standing in the regal shadow of the Bethesda Fountain. It's precisely where Prior recites that final monologue of the play, and it's where Garfield tells me he's eager to see how the latest take on Angels plays in New York -- its true home and, in some ways, its ninth character. Of the triumphant speech, which is meant to send viewers aloft, and out to face the world's unceasing odds, he adds, "It assures the gradual progression of us toward those higher-conscious qualities we're given as human beings. To be a part of transmitting all that feels like the most meaningful thing I could do with my life right now."

He continues, "I'm in a privileged position, and I want to keep listening, and learning as much as I possibly can. I want to be a part of the world spinning forward as much as anyone else."

Photographry: Matthew Brookes

Styling: Grant Woolhead