Every American Apparel store had a stack of Butt magazines. The store manager would seductively place them beside the cash register or otherwise slip them behind a rack of shiny, metallic leotards. Although ostensibly part of the retail brand's highly sexualized shock-and-awe marketing efforts, the presence of Butt inside a major Main Street chain was many queer millennials' first brush with homoerotica.

Related | Butt, Revisited: 10 Years of Radical Homoerotica

Like American Apparel, Butt feels very much like a product of the last decade. It's easy to forget, but the early aughts were a remarkably strange time to grow up queer. On the cusp of mainstream acceptance, young LGBTQ people often saw themselves simultaneously reflected in mainstream advertisements and denounced by the evangelical conservative government. The George W. Bush era spread two contradictory messages to them: one of marketability centered on identity politics and one of absolute condemnation.

Meanwhile, there was a relative lull in LGBTQ activism; the 2000s were a time of transition from the fierce, ad hoc protest of AIDS crisis cohorts, like ACT UP, to today's generation of social media upstarts who partner with larger institutions like the Human Rights Campaign and The Trevor Project. Still, the fallout from the AIDS epidemic haunted the LGBTQ community. At the time, Butt was remarkable for its liberating, unapologetic reexamination of gay erotica, kink, and fetish. But after a decade in production with a modest readership, the zine ceased publication in 2011.

Before queer culture shrugged off its mortal coil and migrated to the datascape, it circulated through hush-hush newsletters and local magazines. The history of gay American mags is predominantly a postwar one, starting in 1950s Los Angeles from within the Mattachine Society. Publications like One magazine--and later the lesbian publication The Ladder--detailed a thriving (if underground) gay scene on the West Coast while resisting censorship by authorities. One Inc., the publisher of its namesake magazine, famously won its 1958 Supreme Court case against the obscenity standards of the U.S. Postal Service. It later became the foundation of today's vital One National Gay & Lesbian Archives in California.

These early iterations from gay history's "homophilia" phase quickly birthed a huge swath of zines in the '60s and '70s that ran on the psychedelic fumes of the Sexual Revolution. The Janus Society in Philadelphia started Drum magazine in 1964, featuring America's first full-frontal male nude layouts alongside news about countrywide sit-in protests against homophobic businesses.

When Butt arrived on the scene in 2001, some four decades later, talk about gay sexuality in the media was decidedly more covert. For many, the AIDS crisis had cauterized conversation about gay sex as too taboo. The politics of visibility orbited around concepts of homonormativity and respectability. The goal was to fit in.

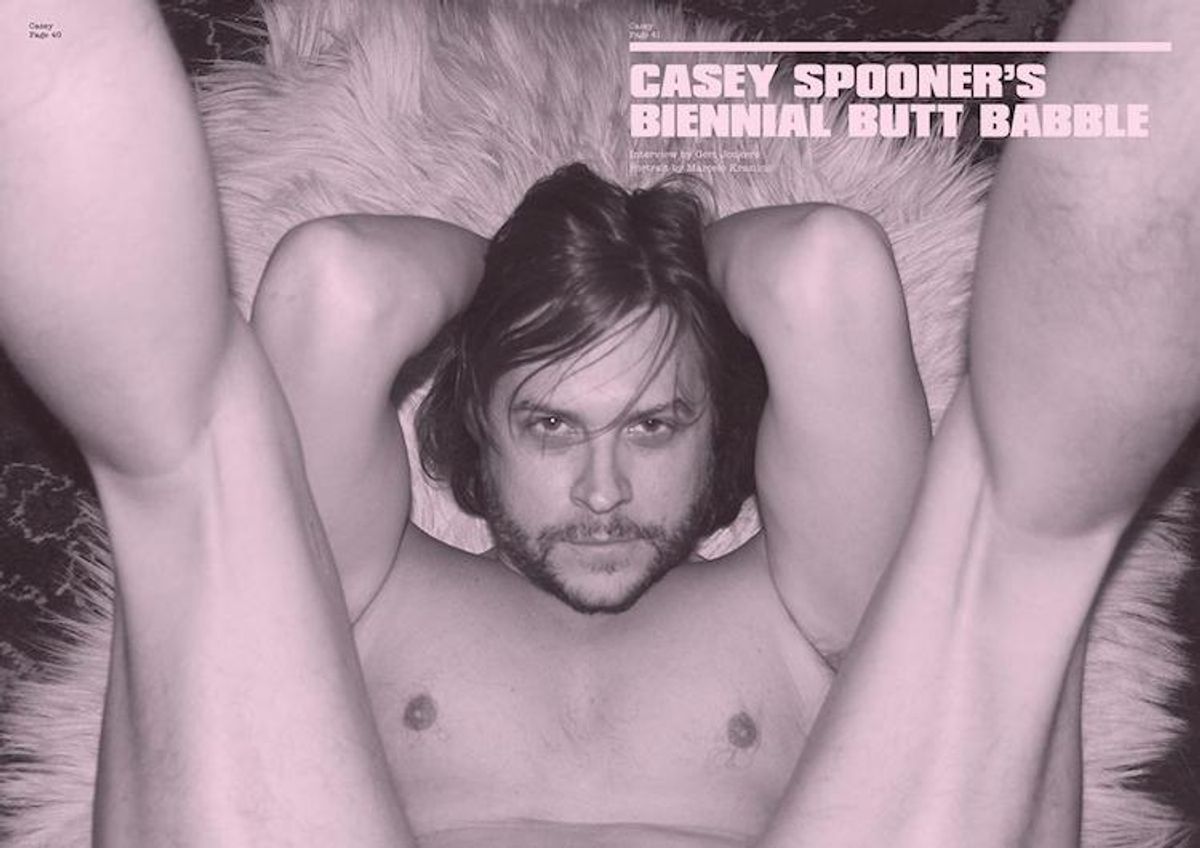

After Butt, a new documentary by artist Ian Giles that recently screened in the U.K., suggests that Gert Jonkers and Jop van Bennekom, the magazine's Dutch founders, were motivated by the desire to put the sex back into homosexuality. The two men had no business plan, just a distinctive idea and look: a low-fi, pulpy zine printed in pink that would feature hunky, hairy models on its covers. At a time when hairless men were very much in vogue, Butt's celebration of butch gays and hirsute femmes signaled a desire to expand the breadth of the queer conversation.

Jonkers and Van Bennekom cultivated an open dialogue with their readership, even printing the occasional lurid fan letter in their issues. Capitalizing on their chatroom legacy, Butt later launched Buttheads, an online social network platform for the magazine's fans. (Giles admits to having a two-month relationship with someone he connected with on the site.)

Giles stitches his various interviews with Butt's founders, fans, and editorial staff together and reenacts them through a discussion group, casting young gay men--likely too young to have been able to buy Butt themselves--to play himself and his interviewees. As a new generation gives voice to the past, we are able to appreciate the subtle dimensions of Giles's defense of Butt. He implies that homosexuality is inherently radical, and that queer zines like Butt are radical insofar as they are stridently sexy.

Perhaps this is why Butt no longer exists. Just as the magazine emerged in a more prudish era, it died in an age that demands intersectionality. Although Butt championed alternatives to machismo and gay homogeneity, it was still an overwhelmingly white magazine with traces of classism and cultural elitism. This haunts Giles's documentary. The internet is a far cry from a queer utopia, of course, but it does offer innumerable avenues for dating, hooking up, and pornography of all stripes. Stuck between Web 1.0 and Web 2.0., Butt typifies why zine culture ultimately failed to keep up with its queer audience. As Giles highlights at the end of the doc, "An independent culture magazine has a certain set of questions--and a certain amount of time."

All photos courtesy of Butt Magazine.