Last July, two full blocks in New York City's Flatiron District were cordoned off after construction workers unearthed a bomb. Vaguely World War II-looking -- silver and ovoid, with long fins -- it sat in a sunken pit of rubble while the bomb squad was called in. Photographers and news helicopters went nuts.

There was no explosive. The glimmering torpedo was a time capsule, buried in the '80s by regulars of the iconic club Danceteria, which closed in 1986. It was filled with letters to the future. "They're probably all rotted away," shrugged the club's owner when reporters tracked him down. "You weren't supposed to find that for 10,000 years."

Related | Where Are All the Angry Young Men?

Rediscoveries are slippery things. Associations and interpretations wax and wane. But this summer, the cultural grenade that was David Wojnarowicz, a former Danceteria busboy, will be reactivated in a major way.

In July, the Whitney Museum in New York City will open "History Keeps Me Awake at Night," the first retrospective of his work since 1999, along with an accompanying book by Yale University Press. It comes six years after Cynthia Carr's 600-page biography, Fire in the Belly, drew raves.

In photography, videos, collage, painting, sculpture, music, and searing books of essays written as if Kerouac and Jean Genet scribbled away on the West Side piers, Wojnarowicz left behind his own missives to the future. He created two of the most iconic images of the AIDS crisis: his mouth sewn shut with blood seeping down his chin, and his face nearly covered by sand and gravel, as if he was being reclaimed by the earth. He had the courage to raise hell in a world where the bottom was dropping out, and in some of the most eloquent language imaginable.

He also knew how to land a punch: "If I die of AIDS, don't bother with burial, just dump my body on the steps of the FDA," he stenciled on the back of a denim jacket he wore to a protest.

But his art isn't just a time capsule.

"From the very beginning, in the late '70s, David's work really had to do with the status of the outsider and American culture," says Whitney collection director David Breslin. "I think that has particular resonance now, when we're thinking about intersectionality. A lot of the things that Wojnarowicz was fighting for through his artwork -- for the rights of people with AIDS, for the First Amendment, for gay men -- could also be seen as analogous to immigrant rights or people we too frequently treat as second-class citizens."

"David expressed the sense that the majority government in America had turned their backs on people with AIDS because they found them largely undesirable and disposable," says filmmaker Joshua Sanchez. "He held nothing back, and it made people in power very frightened. Many people today, especially young people, find themselves in a similar situation with the Trump administration. People can relate to his rage and conviction because they are living through the dark times of a government that they feel does not care about them. We can see this with recent protests about gun control, police targeting of people of color, LGBTQ rights, women's rights -- you see people carrying signs with slogans that David used in his own political actions and his art. He's become a moral authority because his work is so visceral, so direct."

Just as important to rediscover are the spheres of Wojnarowicz's work that exist in a world where there is no illness or oppression, or at least where it's not front of mind. In beautiful prose passages and text-based works, he captured the universal impulses of longing, romance, and straight-up lust, and how they can feel like something close to magic.

Fundamentally, his work tells the story of a guy who always felt like he was from another planet, who voraciously sought love but didn't really know how to receive it, who struggled for success but didn't know how to define it or care much for the glimpses of it he saw. He spoke loudly in a world in which isolation and loneliness were skyrocketing, in a world of advances in which everyone was a double-edged sword.

Related | Fall Into This 'Flamingly Gay' Palestinian Artist's Cross-Cultural Web

Wojnarowicz was born in New Jersey in 1954; his father was an alcoholic, his mother diffident and distracted. Dad took off, Wojnarowicz moved with mom to Hell's Kitchen, and at some point -- even the most assiduous researchers can't agree whether it was age 15, 13, or younger -- he became a dropout, hustling in Times Square.

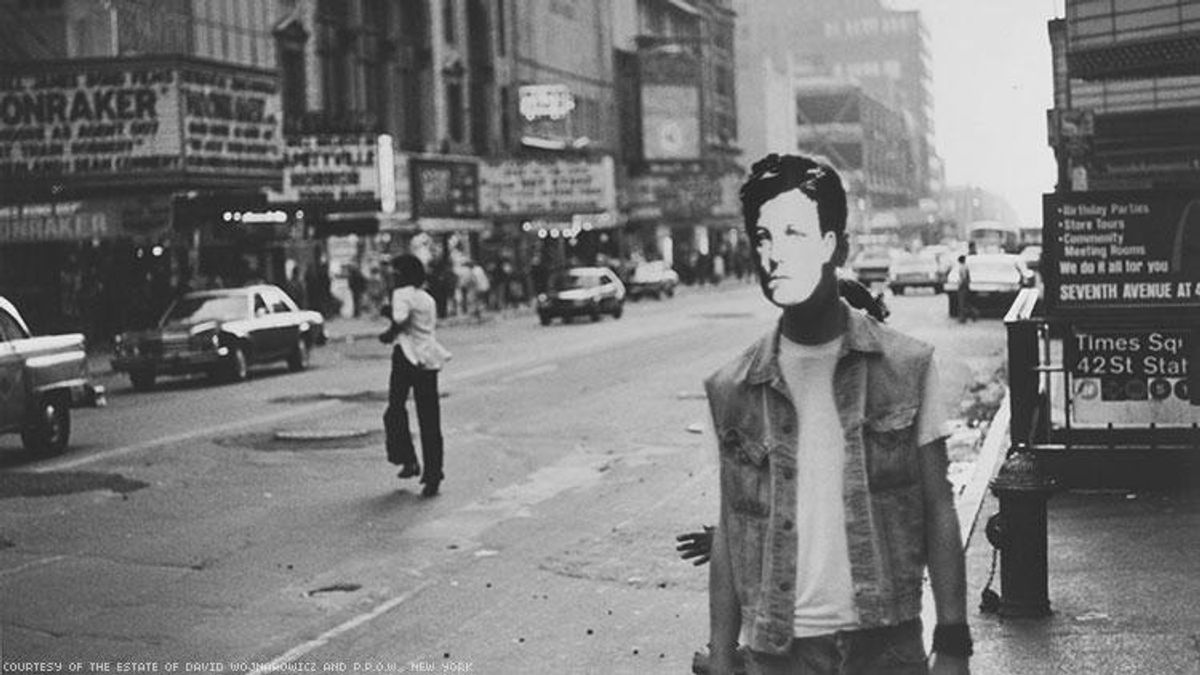

He was a completely self-taught artist. His first piece to make a splash -- and it was a wallop -- was 1979's Rimbaud in New York, a black-and-white photo series in which his friends and lovers wore a photocopied mask of the poet Arthur Rimbaud. Publicly, masturbating, wandering Times Square, and cruising around New York City, Wojnarowicz caught the eye of Peter Hujar, whose stark-but-rich monochrome images rank him as one of the greatest portrait photographers of all time. They were romantic for a month and had a mentor/mentee bond until Hujar's death from AIDS complications in 1987.

Exhibiting in East Village galleries and landing two pieces in the Whitney biennial, Wojnarowicz craved recognition but felt guilty about fame. To get out of his head, he hitchhiked across the country several times, which he used for material in several books, which together were adapted into the film Postcards From America after his death.

In 1991, the year before he died, he published a book of essays titled Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, in which he struggled to deal with his anger at being marginalized in the Reagan era: "I wake up every morning in this killing machine called America and I'm carrying this rage like a blood-filled egg... as every T-cell disappears from my body, it's replaced with 10 pounds of rage."

In the essay "In the Shadow of the American Dream," he wrote, "These are strange and dangerous times. Some of us are born with the cross hairs of a rifle scope printed on our backs or skulls. Sometimes it's a matter of thought, sometimes it's activity, and most times it's color."

But there was gobsmacking beauty throughout. In other essays, Wojnarowicz described a hookup that sparked something like a revelation in him:

"In loving him, I saw men encouraging others to lay down their arms... In loving him, I saw great houses being erected that would soon slide into the waiting and stirring seas. I saw him freeing me from the silences of the interior life."

And then this passage:

"When I put my hands on your body, on your flesh, I feel the history of that body. Not just the beginning of its forming in that distant lake but all the way beyond its ending... I am amazed at how perfectly your body fits to the curves of my hands. If I could attach our blood vessels so we could become each other, I would. If I could attach our blood vessels in order to anchor you to the earth, to this present time, I would. If I could open up your body and slip inside your skin and look out your eyes and forever have my lips fused with yours, I would. It makes me weep to feel the history of your flesh beneath my hands in a time of so much loss... All these memories will be lost in time like tears in the rain."

"I genuinely find it shocking that David Wojnarowicz is known primarily as a visual artist, because for me, his real genius is in his writings," says Christopher Bollen, a novelist and editor for Interview magazine. "His journals and essays pierce the brain with incredibly powerful, sincere, poetic, and frank descriptions of what it was like to be a criminal outcast as a gay man in America. Wojnarowicz can describe a hookup in a car parked on the West Side Highway, hustling for money in Times Square, falling in love with the young man lying next to him in bed, the apocalyptic hate-mob mentality of conservatives, or just drifting around the streets of downtown Manhattan in such a way that you feel almost scoured by his sentences."

"I want people to know how funny he was," adds Tom Rauffenbart, Wojnarowicz's last partner. "He was very goofy, and he was not miserable, although God knows he was miserable sometimes." A fair addendum. There is something hilarious about the idea of a twinky Rimbaud in a sleeveless denim vest, scrounging for dick outside Show Palace.

Another impressive Wojnarowicz production was his ongoing 'Cock-a-bunnies' piece, which featured cockroaches captured in his East Village apartment to which he attached tiny fluffy tails and ears. Feeling aggrieved at being left out of one group show, Wojnarowicz showed up to the opening, let the bunnies loose in the gallery, and put it on his resume.

Rauffenbart, a wiry, snowy-haired 72-year-old, sits in his warm one-bedroom apartment in Washington Heights. A painting of planets, which will be in the Whitney show, and puckish portraits of Wojnarowicz are on the walls. He and Wojnarowicz met in a basement sex club in the East Village, and months of crazy sex led to a seven-year relationship that lasted until Wojnarowicz's death in 1992. Rauffenbart, a preppy civil servant, wasn't into art (he says he still isn't, really); he just felt a powerful connection to this lanky type who was "so ugly he was beautiful."

Toward the end of his life, Wojnarowicz became something of a right-wing chew toy. In 1990, notorious homophobe Donald Wildmon mailed a pamphlet to members of Congress, criticizing the NEA for funding a show featuring Wojnarowicz's works. The artist sued. Even decades later, Wojnarowicz has the power to provoke conservatives: In 2010, then-House Speaker John Boehner complained about a Wojnarowicz video displayed in a show at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. It depicted ants crawling over a crucifix. The museum pulled the piece. "It was outrageous the way they buckled," says Rauffenbart. "I mean, it was really disgusting."

What would David have thought of same-sex marriage? "I can't imagine the two of us ever getting married even if we were together. Maybe weirder things have happened, but I don't think so," says Rauffenbart. "I think he'd be glad, as much as I am, that those who want to get married can get married. They should have the right to it. I doubt very much if we would get married. Or maybe he'd marry somebody else, you never know. If he was healthy, we might have split, and who knows what the future might have been?"

Rauffenbart says that Wojnarowicz would hate Trump ("Hate him!") and be just as activated about the plight of the outsider today. "David would always be angry about something," he says. "Always. It was just part of who he was. He was a warrior."

Sex was a prime motivation for Wojnarowicz, and the Whitney show will include his rarely seen "Sex Series" (1989), black-and-white depictions of the act of coupling, which he produced in Hujar's darkroom after his mentor's death and while he himself was declining.

"This is really a profoundly important work to show both the banality and everyday-ness of sex," says Breslin. "They're almost landscape depictions. But they're also about the real importance of maintaining sexuality at the height of a time when sex was really being denied -- a really fervent embrace of sexuality despite everything, or because of everything."

Wojnarowicz's life on this plane ended in 1992. In 13 years, he left behind six books, enough work that the Whitney show will stretch to 120 pieces, and, ultimately, a type of playbook for surviving the Trump era.

"To me, David is the classic American hero," says Sanchez, who has written a screenplay based on Fire in the Belly. "This is a guy that had the most brutal, abusive childhood you could possibly imagine. Somehow this guy took it upon himself to nurture his artistic gifts and harnessed them as a way out of the streets. His life ended tragically, but to me he's always been a symbol of hope and strength."

Sanchez continues, "Despite being born into a world that didn't want him, Wojnarowicz grabbed something inside him that said, 'Not only am I going to be an artist, but I'm going to be a mirror to how the world treats its outsiders. And you are going to listen.' "

Did 'The White Lotus' waste Lisa's acting debut?