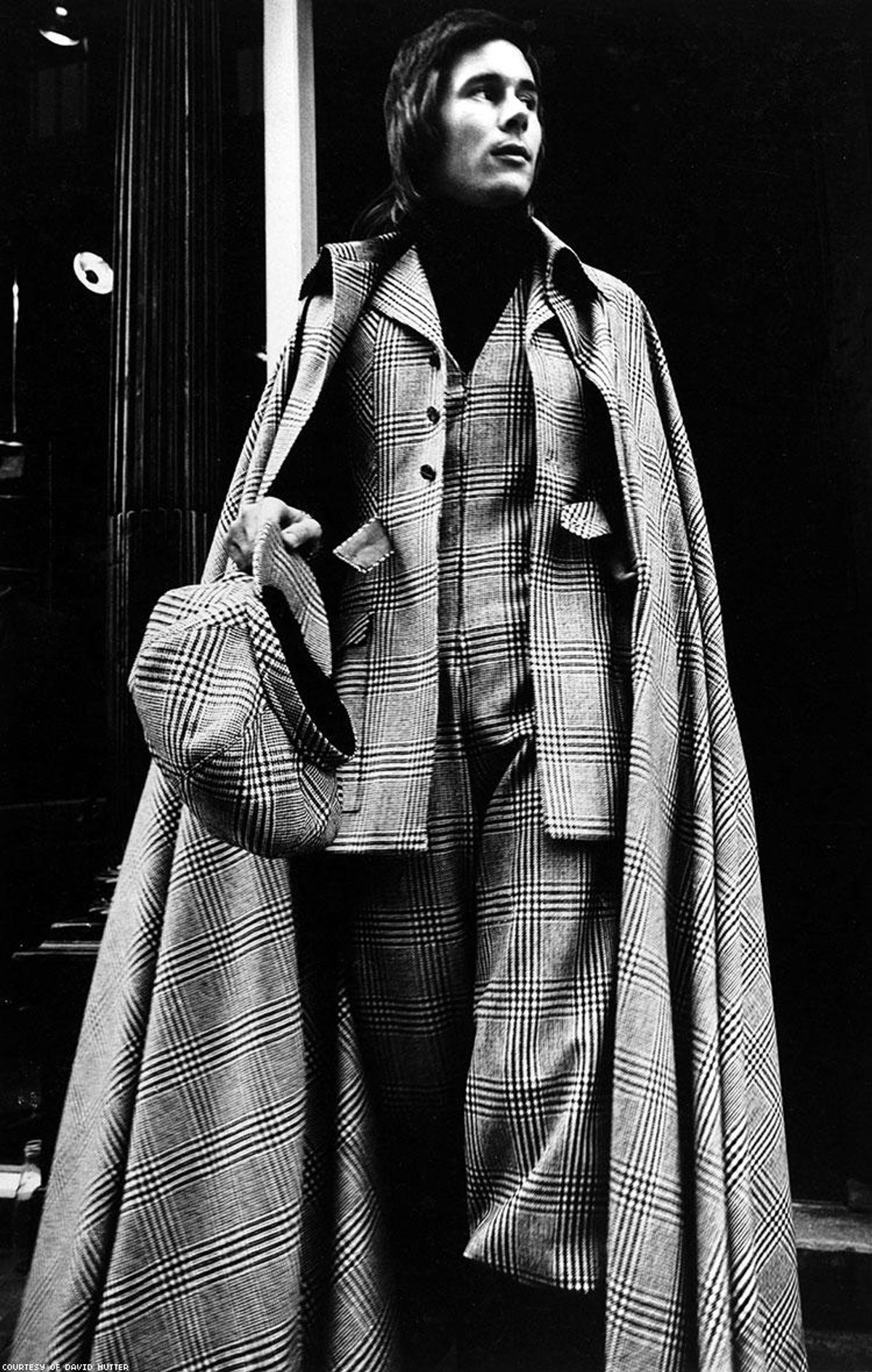

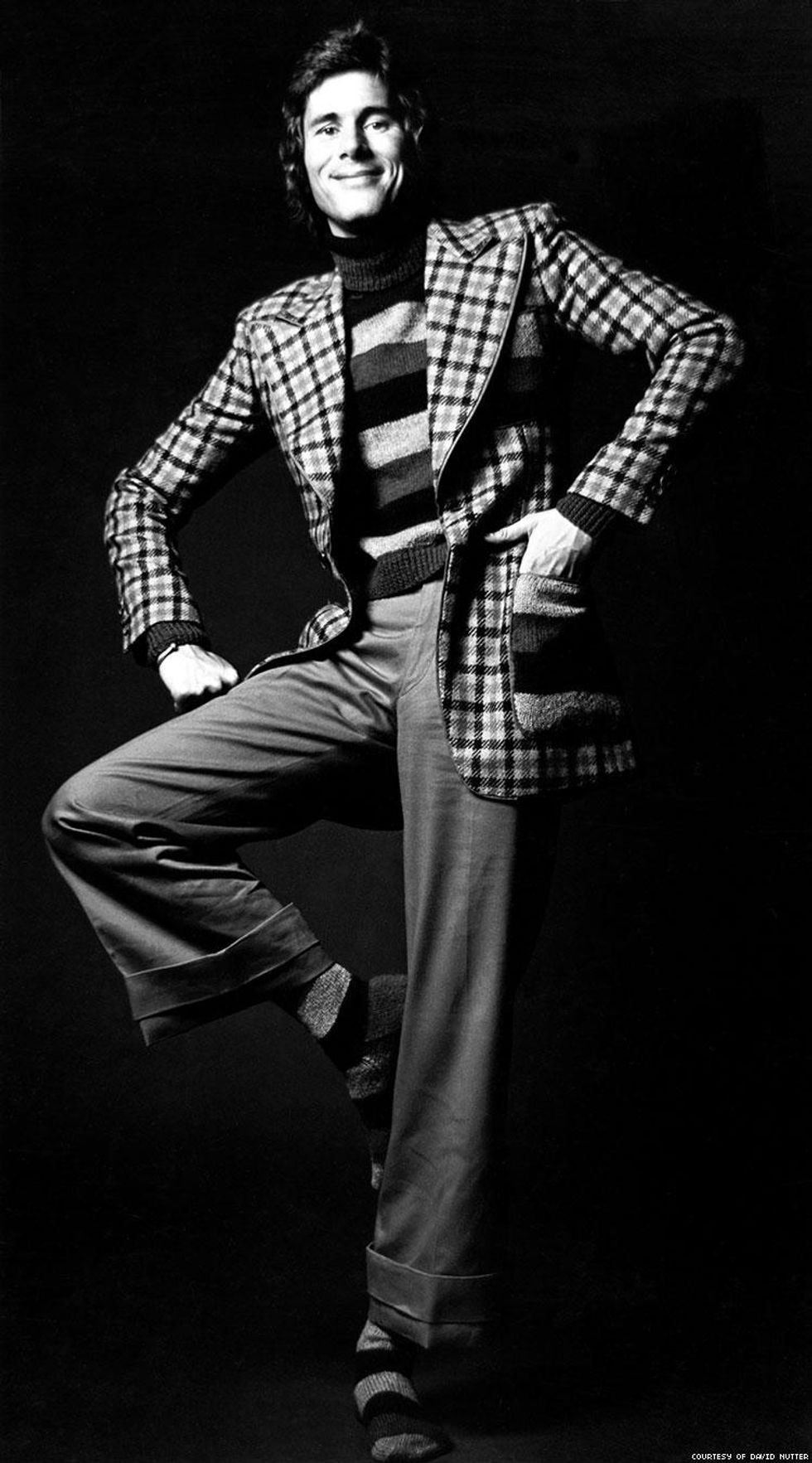

Tommy Nutter lived a life that was, to put it mildly, filled with operatic plot twists. Though most people knew him as the "Tailor to the Stars" -- the bon vivant Savile Row designer who dressed everyone from the Beatles and Elton John to Diana Ross and Twiggy -- his private life was where the most interesting things happened. From underground London clubs in the 1960s, before it was even legal to be gay, to the infamous bathhouses -- and trucks -- of hedonistic Manhattan at the height of the sexual '70s, Nutter was there, both witness and participant. His own biography is also, in miniature, the biography of gay life over the second half of the 20th century -- flagrantly joyful, traumatically brutal. In House of Nutter: The Rebel Tailor of Savile Row, Lance Richardson charts the story of one of fashion's most intriguing figures, including the AIDS diagnosis that would bring his life to an untimely end.

The crowd convened in Fulham's Eel Brook Common, opposite John Galliano's design studio. It was a brisk, blustery Sunday morning in April 1989. Clouds threatened rain with enough conviction that some people had brought their raincoats, though others were committed to their tutus and fairy wings, to showing off rainbow patch pants, Comme des Garcons jackets, antique neck scarves, and brown suede brogues. Roger Dack, the director of Fashion Acts, which had organized the event in London, strolled across the grass with a megaphone rallying his troops. Later, he would describe it as "the most chic walk ever."

More than 900 marchers had turned up, pledging some PS90,000. The official route threaded up the King's Road, through Knightsbridge and Westminster, all the way over to Covent Garden, where the finish line was a Champagne reception at Tuttons restaurant. Bruce Oldfield stood at the front of the procession, itching to go; Galliano, lingering behind a battalion of strollers, brought up the rear.

But first, before anyone could take a single step forward, 1,116 red balloons were released into the sky: one for every person in the country who had died from AIDS-related causes.

Early in the epidemic, AIDS had been dismissed by some members of the British public as "an American problem" that would never creep its way across the Atlantic. Of course, it had already arrived; in 1982, a man named Terrence Higgins had collapsed on the dance floor at Heaven and died a few months later from Pneumocystis pneumonia. "I hope you get very scared today because there is a locomotive coming down the track and it is leaving the United States," Mel Rosen, an American AIDS activist, had warned at a conference in London the following year. By late 1985, there were 241 cases of AIDS in Britain, and newspapers were reporting instances of "scared" firemen and paramedics who were refusing to perform the "kiss of life," lest they get infected. In 1987, as conservatives talked seriously about compulsory testing of all gay men and possibly even mass quarantine, the science correspondent of the London Times wrote that "leading specialists believe... between 40,000 and

100,000 people in Britain are now carriers."

As the red balloons drifted into the sky above Fulham, Tommy Nutter took swigs from a hip flask to fortify himself for the long march to Covent Garden.

The first black spot had appeared on his own leg toward the end of the 1980s: small, dark, refusing to heal.

Stewart Grimshaw, one of Tommy's close friends, first noticed it when they were summering together in Saint-Tropez. Others noticed because Tommy drew their attention to it, making light of what the mark could possibly signify. When Carol Drinkwater read an article describing Kaposi's sarcoma lesions, the reddish-purple patches often associated with AIDS, she asked Tommy if he had anything like that. He replied, "Yeah, yeah," indicated his leg, and shrugged away the question. But then the spot got worse, his health took a turn, and ignoring it became impossible.

Many of the gay men Tommy knew went to St. Mary's Hospital, in Paddington, to be screened for sexually transmitted diseases. But Tommy refused; he hated being seen in that environment. Instead, he went to see Stewart, who, Tommy knew, had been actively involved in AIDS awareness since the days it was known as the dreaded "gay cancer." As Stewart recalls, "He came to me because he had loads of questions, and he thought I'd have all the answers."

For example: How many people get over it?

Stewart told him that nobody "got over it."

And how long before...?

That depends on your T-cell count, Stewart said.

After Tommy exhausted his inquiry, Stewart convinced him to follow up with a brilliant clinician named Brian Gazzard. Having encountered his first case of what became identified as AIDS back in 1979, Gazzard was one of the leading medical authorities in Britain. He'd already seen hundreds of HIV-positive patients by the mid-1980s, and more recently, he'd been instrumental in setting up the Kobler Centre, a dedicated HIV/AIDS research and outpatient facility funded by a combination of private donations and money from the National Health Service. (Princess Diana opened the day-care wing during a well-publicized visit in 1988; it had been packed with patients ever since.) The Kobler saw "a never-ending procession," Gazzard recalls, and the atmosphere was both depressing -- with up to 10 deaths a week -- and inspiring, because "people were full of courage and determination."

Tommy made an appointment to see Dr. Gazzard, but he didn't want to go alone. He asked Stewart to keep him company.

The doctor sat them down in a quiet office. He told them that some people wanted to hear all the details, while others didn't want to hear any of the details.

Tommy said, "Tell me everything."

"But that's not really what he wanted," Stewart recalls.

What Tommy would have been told is something like this: That there is no easy way to break bad news. That, according to his test results, he was HIV-positive, with a very low CD4 cell count. That he already had opportunistic infections, and there was a good chance he would contract even more. That the treatments available to him were limited -- AZT, perhaps, though its effectiveness at prolonging life was finite and accompanied by side effects. That most types of treatment would focus on infections rather than the virus itself, which could not be cured. That there would be ways forward, however, to remain in control of the situation. Because that was the most frightening thing for patients newly cognizant of their status: the prospect of losing control.

Stewart listened carefully and understood exactly what was going to happen to his friend.

Tommy also listened, silent until the doctor finished and asked him if there was anything further he wanted to know.

Tommy thought for a moment. Then, Stewart remembers, he said, "Yes, there is one thing I'd like to know. I'd like to know when Mack and Mabel is opening in the West End."

Mack and Mabel was an American musical by Michael Stewart and Jerry Herman that had premiered on Broadway in 1974, but thus far failed to transfer to London, except for a one-off charity performance at Drury Lane, in 1988. It told the tragic "true" (heavily fictionalized) story of Mabel Normand, a working-class girl who became a glamorous star of silent cinema before sliding into scandal and ultimately dying from pulmonary tuberculosis at the premature age of 37. Tommy had acquired a cast recording, and declared to several friends that it was his new favorite show.

The doctor stared at Tommy.

"I truly think he thought that Tommy already had dementia," Stewart recalls.

When Tommy arrived home that evening, he telephoned Carol Drinkwater, whom he'd known since they met at a nightclub called La Douce in the early 1960s.

"What is it?" Carol asked. She was standing in her upstairs bedroom.

"I've got AIDS," Tommy said.

Carol took a deep breath. "Tommy, you've got to be positive."

"I just said that," he snapped. "I am 'positive.' "

Once Tommy knew for sure that he had HIV, his first response was to make jokes, and his second was to adopt a kind of optimistic denial. "In the first six months, he was very sure that something would be done and that he would be OK," recalls Tim Gallagher, one of the salesmen in Tommy's Savile Row emporium who had also become a close friend. "I think he took it very well indeed." Occasionally, Tommy called up Stewart to ask some more questions: What about that new drug mentioned in the newspaper? What about this experimental form of treatment? But mostly he preferred not to discuss the situation at all, carrying on as though absolutely nothing had changed. Which is not to say, however, that he wasn't affected. His assistant, Wendy Samimi, spent enough time with Tommy to notice cracks in the carapace. Despite his demeanor of cool unconcern, she could tell that he was rattled. "Would it affect his brain? Would he get all the sarcomas? It could manifest in so many different ways -- that's where his demons were about it."

These demons manifested most clearly whenever it came time for another doctor's appointment, now regular and essential. Visiting the Kobler meant Tommy could not pretend that everything was just the same; it forced him, for a few hours each month, to confront the full spectrum of AIDS, from patients like him with mild ailments right through to those in terminal stages -- his probable future, given it was still more than five years before the life-saving cocktail would be released.

The days leading up to his treatments were "awful," Wendy recalls, "because he'd be hell at work. You could see it: ginning himself up to go. Really didn't want to go. Probably a bit angry. A bit hard on people, which was not like him."

Adapted from Lance Richardson's 'House of Nutter: The Rebel Tailor of Savile Row,'available now through Crown Archetype.