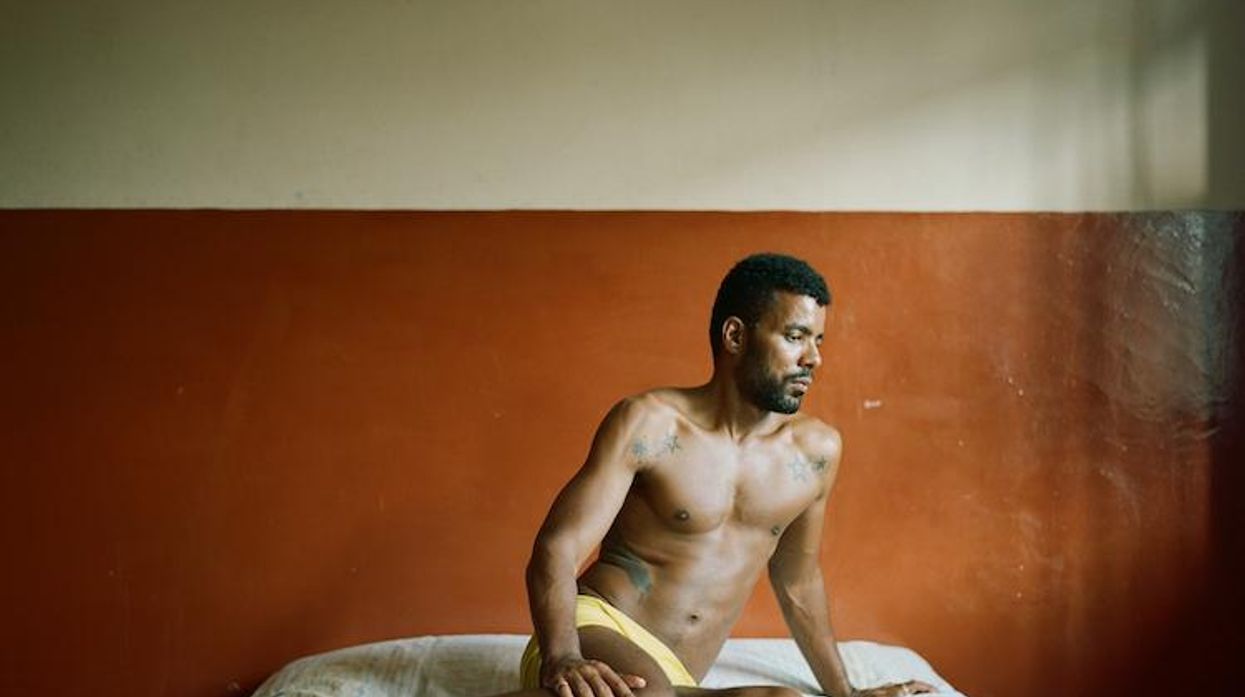

Hotel Luso is no Best Exotic Marigold or Grand Budapest establishment. You won't find a wily cast of old British actors or Dev Patel. You won't find the Wes Anderson mainstays running through painfully symmetrical sets. At Hotel Luso, an old Portuguese hotel turned pay-by-the-hour, there's a sense of safety in the art deco interiors under the lens of Daniel Jack Lyons.

For the photographer and human rights activist, the faded glory of the hotel was the perfect location to capture the spirit of some of the queer Mozambicans he's met over his years of work in the country. Since coming to the country in the mid-2000s to work on public health projects throughout the country, the New York-based advocate witnessed firsthand the evolution of LGBTQ rights in Mozambique. Still, despite the national legislature passing some of the most progressive anti-discrimination laws on the continent, he also saw the stigma that his friends within the community continued to struggle against.

Related | Mozambique's LGBTQ Community Finds a Home in 'Hotel Luso'

"Mozambique has very progressive anti-discrimination laws, but a larger cultural silence persists. That silence restricts the behavior of queer youth who live in multigenerational households and depend on their families' support," he explained over email. "So many of my collaborators did not feel comfortable taking pictures in their homes." It was while working on another photo project about sex work that Lyons found the old colonial art deco building that became the centerpiece for Hotel Luso. "It became a neutral space for us to occupy -- one that was symbolic of the kind of love that is hidden and unseen."

Following his recent photo series Displaced Youth, which documented queer Ukrainians displaced in the Russian military invasion, and 2016's MAHOTAS, visualizing the resilient patients seeking mental health services in Mozambique, Hotel Luso continues his work of championing LGBTQ communities around the world.

We caught up with the photographer while he took a break from traveling to talk about the LGBTQ Mozambican activists who helped inspire Hotel Luso and why the new generation of queer people are risking everything to live openly.

OUT: How did you come to meet the queer Mozambicans that you featured in this?

Daniel Jack Lyons: My connection to the Mozambican LGBTQ community began in the mid-2000's when I spent nearly four years working on public health projects throughout the country. During that time there were no gay organizations, let alone gay bars, clubs or public spaces for people to meet. Socializing was much more clandestine, involving mostly invite-only parties at private residences.

At one of these, I met Danilo DaSilva who founded LAMBDA -- the first, and still only, queer rights organization in Mozambique. Over the years, I kept in touch with Danilo and his associate at LAMBDA, Frank Lileza. As my work shifted towards photography and human rights, they helped connect me to a new generation of queer people growing up and coming out in Maputo. Meanwhile, I met Yuki Miranda, a Mozambican performance artist who has helped me forge connections with Maputo's new wave of visual and performance artists who have inspired my work here.

How did you decide on the hotel as the place to photograph them? Was there anything particular that you were drawn to there?

I'd been photographing Mozambique's queer community for several years, but had become frustrated trying to find authentic spaces to shoot. Much of this had to do with the still lingering taboos related to sexual orientation and gender fluidity. Mozambique has very progressive anti-discrimination laws, but a larger cultural silence persists. That silence restricts the behavior of queer youth who live in multigenerational households and depend on their families' support. So many of my collaborators did not feel comfortable taking pictures in their homes. And likewise, most public spaces felt unsafe. I tried taking portraits in my apartment, but it felt staged.

I found the hotel by chance while working on another project related to sex work. It's an old colonial art deco structure, with massive windows and doors that open up onto large balconies that hang over the street. It's mostly used at night as an hourly motel, and was completely empty during the day. This was the perfect space, available and actively ignored. I proposed the idea of shooting there to everyone I had been working with, and they really embraced it. It became a neutral space for us to occupy -- one that was symbolic of the kind of love that is hidden and unseen. Which is appropriate since this series is all about visibility and shining a light on a community that is otherwise unseen because of who they love.

You've been in Mozambique on and off since 2005. What brings you back?

My friends there have become like family over the years. Returning to Mozambique feels much like going home. I speak the language and have friends spread throughout the country that I've known for over a decade now. Through those relationships, I've also developed a network of organizations and groups who have hired me to go back to work on various human rights-related initiatives. In the last three years, I've averaged four trips a year.

How have you seen the country's attitudes toward LGBTQ equality shift in the past 13 years of visiting there?

As I mentioned, the stigma for being queer is still intense. It affects where and how my collaborators and I could document and share their experiences. And it influences more significant decisions, like whether or not to pursue a relationship [or] to live with a partner. In spite of my disappointment regarding this larger cultural stasis, I've been inspired by the new generation of young queer people who are defying those circumstances and risking everything to live openly. Those risks are real and consequential, though. And there is still a very long road ahead to achieve an enduring and visible queer community in Mozambique.

In interacting with the subjects of the series, what was the most inspiring moment or message that you took away from it?

One of the most rewarding aspects of this series was the time spent with my collaborators, getting to know each person in an intimate way and hearing their stories. As I listened, it was hard not to compare their experiences to my own as a gay man in the US. I was reminded that even when the law is on your side, the struggle continues. We've celebrated some major victories like marriage equality, but we still have a long way to go, especially as it relates to our trans sisters and brothers.

As the world continues to become more interconnected, it becomes more important than ever for us to stand up for our queer families around the world. Whether in Russia or Uganda, we are all connected and we have a responsibility to our global queer families everywhere.