In Berlin, I do not know which friends identify as queer and which do not. I love not knowing. Straight men dabble, show up at techno parties in jockstraps, harnesses, and rubber — and go for women. My grip on my own sexual identity has dissolved. This started long before moving here; my first book was, among other things, about how I never settled on a label. But Berlin has cemented this: I am label-less. In the city’s party scene, the boundaries between queer and straight collapse.

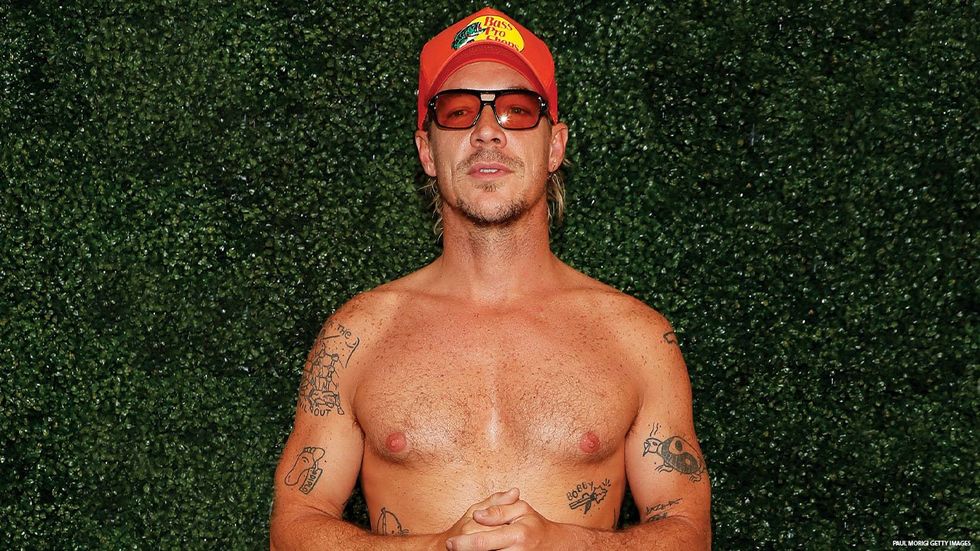

Superstar DJ Diplo has never come out as gay or queer, but he made headlines in March for saying he likes blowjobs from men and is “not not gay.” On cue, articles featuring shirtless Diplo pics appeared on the internet buzzing over his non-confession, which was not so much a coming-out as a refusal to self-label.

My two cents: His identity is his business. I see his comments as evidence of a future where “gay,” “queer,” and other labels are obsolete. A world where people are free to call themselves what they want or avoid labels entirely. A world like Berlin clubs, where sex just means asking, Do you want to fuck? Yes or no?

I work in nightlife with music people, so I decided to get feedback from some of them. An Atlanta-based DJ named NSA, who would not share pronouns, said they no longer care if an artist is queer. “I don’t relate to the idea of coming out. If sexuality and gender are irrelevant, I’ll treat them that way.” Then, as if speaking from my heart, they add: “Queer is dead. I’m a f****t.”

From Brooklyn, Boy Radio — an avant-pop artist who uses he/they pronouns — says it still matters when musicians come out, so long as they feel safe, but that queer now just means “other.” It “goes against the norm, not necessarily as an act of rebellion, but because it’s not what is expected,” he shares. “Lady Gaga is a straight woman but a queer artist. A straight person, ally or not, can be queer. Some individuals have open relationships that aren’t defined by orientation. That is a queer way of living their truth.”

For some, this is troubling. Many gay men fear their spaces are vanishing — and they are. Gay bars have shuttered across the U.S. (and the world) as gay culture dissolves into something more flexible and accessible. Queerness can now be tapped into by those who do not share the painful (and painfully unifying) experiences of social isolation, violence, rejection, and coming out. Can anyone be queer?

Yeah, I think so. That’s how it feels in Berlin, and it’s beautiful. But Berlin isn’t everywhere. In Kenya, men who have sex with men can be imprisoned for life, and transgender folks face ongoing legislative attacks from lawmakers in the U.S. Most people still see queerness as separated by hard lines. To our foes, we exist beyond this line as an altogether different class of people: threatening and unfamiliar.

Diplo and others like him should disturb our enemies’ assumptions about how human beings work — and ours too. He joins many artists, past and present (like David Bowie, Suzy Eddie Izzard, Harry Styles, Madonna, and Grace Jones), who have shown that sexuality and gender can resist easy categorization — that they are, in fact, inventions. Music is where people tend to play with all this stuff: where Katy Perry kissed a girl and liked it, where historically, Elton John and Liberace found a way to embody pure queer camp without being out.

With Pride coming and more debate on what we are now — what “queer” is, what it all means — I decided to ask a friend who could give me a glimpse of the past. Danny Fields is 83 and has been out all his life. A major figure in the history of American music, Fields signed and managed Iggy and the Stooges, signed the MC5 and managed the Ramones, and worked in various roles with Jim Morrison, the Velvet Underground, and the Modern Lovers. He was buddies with Nico and Leonard Cohen. In conversation, he casually drops names like Janis (Joplin) and Patti (Smith).

“Tell everyone to calm down,” he said. “This guy [Diplo] likes blowjobs. Who cares? Doesn’t everyone?”

I asked him if male celebrities could make comments like Diplo’s without repercussions in the ’70s and ’80s. This prompted a story about Elton John. “I was working for 16 Magazine, a celebrity fan magazine for teenage girls, when Elton came along. Our readers were obsessed with him. Then he did an interview with Rolling Stone in which he came out as bisexual. Those who knew him just chortled. Everyone in New York and London knew Elton was not bisexual — he was gay. But fans were appalled. The magazine got thousands of letters from fans asking for the truth. Their older brothers read Rolling Stone and told them Elton was bisexual, and they wanted our magazine to say he wasn’t.”

In response, Fields wrote an editor’s letter: Yes, it was true. After all, he said, it was hard to deny the words when they came from the artist’s mouth. “I wrote, ‘What does this have to do with how much we love Elton and his wonderful songs? If you are a true fan, this is a time he could use your support.’”

Even so, Fields said the fan mail vanished, and Elton had a dark time. This was the early ’70s, and there were repercussions then. But Fields was always out. “Out?” he asks. “I was never in!” He said that, back then, coming out meant telling your parents — not everyone. “Anyone who knew you and worked with you knew. It wasn’t a splashy thing. It was a matter of indifference for us in New York, Hollywood, and London. You expected that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards did blowjobs with dudes, and it was no big deal. It just didn’t matter. Everyone helped you keep all this from the press, and at some point, you had to get fake-married in your 40s or 50s. But that was the job, especially if you were in the movies. If you were in the industry, you kept your secret and helped others keep their secrets too.”

The inner sanctum of his rock world — a place of relaxed boundaries — sounded like Berlin: a bubble in which blowjobs and sex did not correspond to fixed identities. I realized that Danny and I (and Diplo and others) shared a world beyond the regular one, far removed from the homophobic towns we escaped. If queer culture starts in cities and creative hubs and spreads outward, our future is fluid: Queer will diffuse into a culture where there are no straights or gays, just people who don’t care either way.

And this is good. We can let the past go. If queerness risks being obsolete, perhaps it should be. Maybe this is what happens when everyone is truly free to be what they want, when sexuality and gender are truly fluid. Isn’t this what we’re fighting for? Our own obsoletion? A world where folks can be gay, straight, or shrug labels entirely in favor of something playful and ineffable, a true “free love” utopia?

Desire can be a loose-fitting skin, not a lockbox to live in. I used to bemoan how “queer” felt like a permeable membrane between gay culture and everyone else. But I’ve changed. I was clinging to a past that no longer defines our world. I hope we move beyond hard lines. I hope we all become people who play with and take care of each other. I don’t know how to get there, especially in places where we still experience so much hatred and violence. But I can taste that future on the dance floor — when everyone in the room feels like one body, one love.

Alexander Cheves is a writer, sex educator, and author of My Love Is a Beast: Confessions from Unbound Edition Press. @badalexcheves

This article is part of the Out May/June issue, available on newsstands May 30. Support queer media and subscribe -- or download the issue through Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.