Many people consider the Stonewall uprising to be the beginning of the modern gay rights movement. But before the raid that launched a thousand Pride parades — and many more rainbow-washing advertisements — activist entrepreneurs were leveraging capitalism to build both queer equality and community, work that later secured one of America’s earliest Supreme Court victories for gay rights.

Our cast of characters includes Bob Mizer, H. Lynn Womack, Physique Pictorial, and plenty of all too familiar “think of the children” anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric that has persisted for decades, most recently in today’s political vitriol and legislative tomfoolery regarding drag and gender.

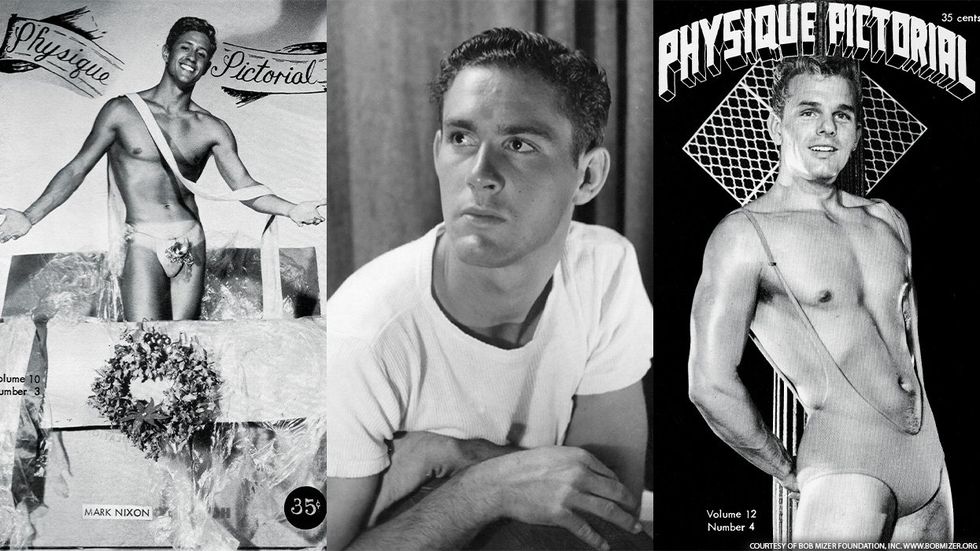

Even if you don’t know physique publications by name, you know the references when you see them. The black-and-white illustrations of muscle heads and Grecian warrior-inspired pinups are considered vintage today. But in the 1950s and ’60s, they were an entrepreneurial publishing vehicle that educated and connected tens of thousands of young gay men, many of whom otherwise felt alone. Think Minx — the Starz comedy about an erotic but erudite women’s magazine in the ’70s — but with editorials on gay stuff instead of feminism.

A frequent rallying cry of gay rights activists is that “it’s a movement, not a market.” For a community to rally, however, the community must first exist. Here’s the CliffsNotes version of some of America’s earliest gay pinup magazines, the challenges they faced along the way, and why the victories they secured have shaped modern gay male culture.

Bob Mizer and Physique Pictorial

Physique Pictorial founder Bob Mizer was outspoken from a young age. Example: He was writing columns championing queer advocacy for his high school newspaper…in 1940. Five years later, upon gaining interest in fitness culture, he submitted a notice to the pen pals section of the magazine Strength & Health, because slip-slidin’ into people’s DMs wasn’t a thing back in those days, so this was all the boys had. Mizer even included his home address in the blurb. When he received over 300 responses, the young writer’s instincts were confirmed: Gay men love a good thirst trap, but they also want companionship and a respite from loneliness.

Beefcake culture had surged in the 1940s, creating an opportunity for Mizer to enter the world of physique photography. Armed with a camera and a reasonable-enough commute to Muscle Beach in Santa Monica, Calif., he began photographing models and creating photo books, which he then advertised mail orders for in the back pages of Strength & Health and other publications. Authorities later deemed offerings like Mizer’s books obscene and threatened the magazines’ mailing permits, which were a lifeline at the time, if they continued to allow the advertisements.

Nevertheless, the demand had been proven. After being blacklisted and serving a prison sentence on a work farm for convictions of obscenity, Mizer wanted to start a magazine of his own. In May 1951, he released the first issue of Physique Photo News, and before year’s end had rebranded it to Physique Pictorial, which overtly appealed to a gay audience. Other magazines, such as Tomorrow’s Man and Grecian Guild Pictorial, soon followed. In addition to photography, issues included reporting on legal cases related to obscenity charges as well as narratives that supplemented the photographs, depicting the models as intelligent and ambitious, a departure from society’s labeling of gay men as degenerate and mentally ill.

Bob Mizer

Bob Mizer

“We think of the gay market as a by-product of the movement, but what my research shows is that the market preceded the movement,” says David K. Johnson, Ph.D., history professor at the University of South Florida and author of the book Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement. “Gay people were able to see themselves first as a market through these publications. They could see that there were thousands of other men buying these magazines and writing in.”

Mizer’s photographic style included men posing in “duos,” a format that enabled homoerotic fantasy and distinguished the brand from mainstream fitness publications. Even though the magazine was a business, Mizer didn’t copyright the issues until 1978 because he assumed the U.S. Copyright Office would deem the content obscene. As a result, issues entered public domain as soon as they were published, which helped bolster distribution of Physique Pictorial in the decades that followed.

“There was a sense of community,” says Johnson. “And then it was also seen politically as fighting back. [The magazine] is saying, ‘We need to fight back as a community, we’re a community under siege, and we’re being attacked by the government.’”

The physique photographers from this period weren’t exactly angels, though. Some photographed underage models, intentionally misreporting their ages by a year or two to get around censors. Others slid into behavior deemed lascivious at the time, resulting in arrest. Nevertheless, through storytelling and distribution, a national queer market became increasingly aware of its own existence.

The Business of Spreading a Message

COURTESY OF ONE ARCHIVES AT THE USC LIBRARY (ONE MAGAZINE)

COURTESY OF ONE ARCHIVES AT THE USC LIBRARY (ONE MAGAZINE)

Fitness magazines weren’t successful because of subscriptions or individual issue sales. Instead, they made their money in equipment sales, doubling as product catalogs for items like barbells and plates. This entrepreneurial formula for media persists even today: Grindr launched its media brand Into in 2017, for example. For Physique Pictorial and other magazines, the wares weren’t weights but instead were look books and short films. These offerings led to years of scrutiny from both government organizations and local law enforcement, often resulting in intimidation tactics directed at newsstands.

Because of this, no one could really crack this distribution problem until H. Lynn Womack came along in the late 1950s. By bolstering business relationships that ensured his magazines could be sold nationwide consistently, he was able to grow a publishing empire, acquiring properties like Trim, Grecian Guild Pictorial, and — my favorite, because I love both muscles and puns — MANual. After being arrested for sending obscene materials through the mail in 1960, Womack appealed his case all the way up to the Supreme Court.

“It was one of the first human rights cases, and it was about magazines,” says Johnson. “Everyone acknowledged it wasn’t really about the level of obscenity or showing more skin than any other magazine, but rather that they knew that the audience was gay men. [Womack] was able to make that argument in court.”

COURTESY OF DAVID K. JOHNSON (H. LYNN WOMACK)

COURTESY OF DAVID K. JOHNSON (H. LYNN WOMACK)

The size and influence of Womack’s businesses helped buoy his appeal to the Supreme Court, a consideration that eluded other important activists of the 1950s and ’60s like Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., founder Frank Kameny, a civil servant who was fired for being gay.

In 1962, a sharply divided Supreme Court found in MANual Enterprises, Inc. v. Day that lower courts had erred because they had defined materials as obscene solely because of their intended audience (gays!). The decision was a landmark gay rights ruling, and one that would protect the physique industry from censorship overreach and fuel queer activism for years to come.

“The magazines showed that there was this thirst for connection,” says Johnson. “They offered pen pal clubs, which were essentially the Grindr of 1961. People wanted to connect. You could be in a small town in North Dakota, or Tampa, Florida; it didn’t matter where you were.”

By using commerce to fund a message, activist entrepreneurs of the mid-20th century were able to cultivate a sense of belonging. Even in the face of intimidation, they took action and banded together. As the future of queer acceptance hangs in the balance, drawing upon our own history and the strength of generations past will inspire energy and action when we need it most.

A self-described “editorial mutt,” Nick Wolny is a journalist and consultant. He writes about money, business, LGBTQ+ life, and how they intertwine, and has previously contributed to Fast Company, Business Insider, and Entrepreneur magazine. Join his newsletter at NickWolny.com. A special thanks to David K. Johnson, whose scholarship inspired this article.

This article is part of the Out September/October issue, which is now available on newsstands. Support queer media and subscribe — or download the issue through Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.

Bob Mizer

Bob Mizer COURTESY OF ONE ARCHIVES AT THE USC LIBRARY (ONE MAGAZINE)

COURTESY OF ONE ARCHIVES AT THE USC LIBRARY (ONE MAGAZINE) COURTESY OF DAVID K. JOHNSON (H. LYNN WOMACK)

COURTESY OF DAVID K. JOHNSON (H. LYNN WOMACK)