This story is published in partnership with The Center for Public Integrity.

About 1.4 million people in the United States identify as transgender at a time when President Donald Trump's administration has been particularly hostile toward the "T" in LGBTQ+ -- from trying to ban transgender individuals in the military to considering a federal definition of what constitutes gender.

Meanwhile, there are zero openly transgender Americans serving in Congress. At least 51 transgender people unsuccessfully ran for state, local, and federal office last year, according to data collected by Logan Casey, a political scientist who now works with the Movement Advancement Project. Nine ran for Congress, but none emerged victorious or even won a major-party nomination.

Such political futility for transgender Americans specifically comes at a time when gay, lesbian, and bisexual political candidates are winning some of the nation's highest offices and even running for president in 2020.

A major obstacle for transgender candidates is money: Those nine transgender congressional candidates collectively raised less than $300,000 during the 2018 election cycle, a Center for Public Integrity review of federal records indicates.

Only three of them -- Democratic candidates Alexandra Chandler in Massachusetts, Brianna Westbrook in Arizona and once-imprisoned whistleblower Chelsea Manning in Maryland -- raised more than $5,000 each. (During the 2016 election cycle, the average winner of a U.S. House seat spent about $1.5 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.)

Meanwhile, there were no exclusively trans-focused political action committees or super PACs raising and spending significant amounts of money to help transgender congressional candidates' campaigns.

It wasn't supposed to be this way: Trans United Fund, a PAC organized in October 2016, sought to fill that void through its PAC and 501(c)(4) social welfare nonprofit arm. The group's launch garnered national attention, its leader spoke of involving Trans United Fund in federal elections -- including presidential campaigns -- and its emergence came with the promise that it would boost transgender political representation.

But the Washington-based PAC has not yet raised a single dollar for federal-level candidates, according to Federal Election Commission records. While Trans United Fund endorsed three winning transgender candidates who ran for state or local offices in 2017, including Democratic Virginia General Assembly Delegate Danica Roem, the PAC has struggled to convert these successes into significant cash.

Headwinds for Trans United Fund include competition from more established political groups that advocate generally for pro-LGBTQ+ candidates, the absence of wealthy, founding donors to kickstart its operations and an American public that's still understanding what it means to be transgender.

Trans United Fund's lack of financial muscle and the dearth of other organizations like it could hinder transgender candidates' viability in the future.

Creating a PAC centered on transgender candidates

Trans United Fund was founded by Minneapolis City Council member Andrea Jenkins -- the first openly transgender African-American woman elected to public office -- and political strategist Hayden Mora.

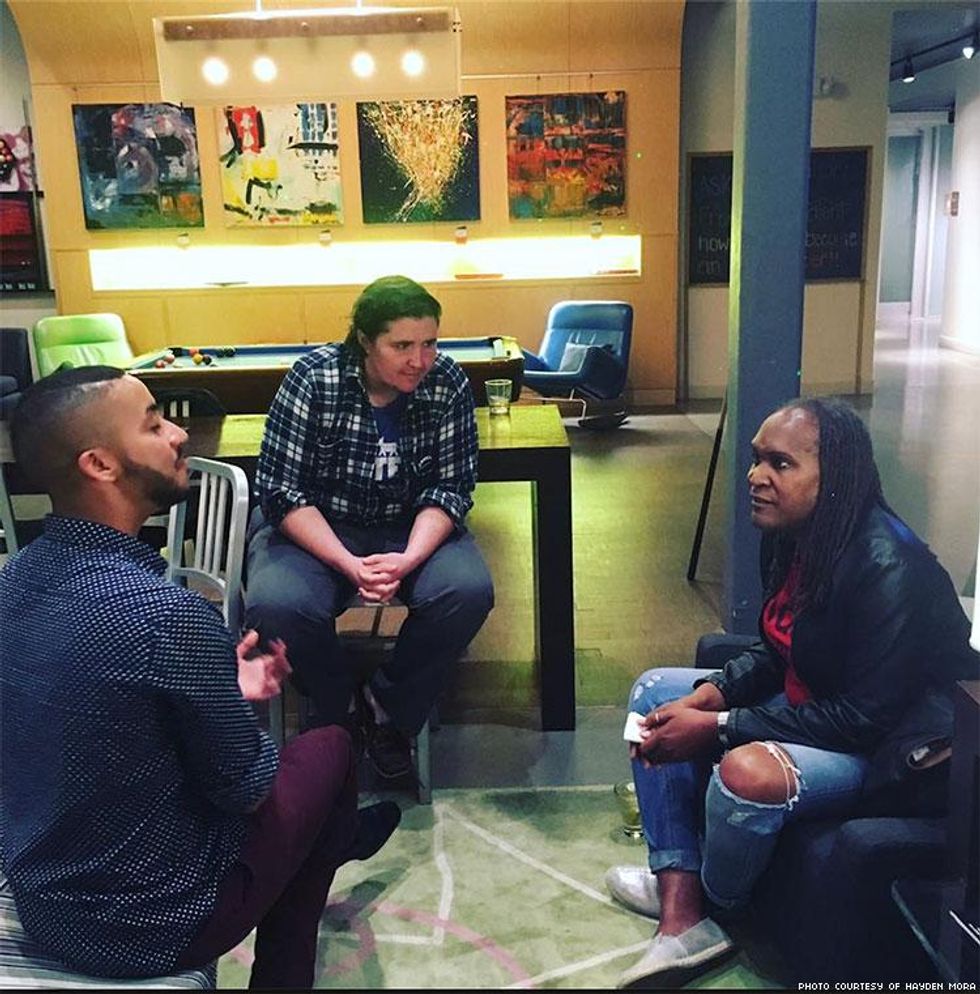

Phillipe Cunningham, Hayden Mora and Andrea Jenkins discussing goals in North Carolina in 2016.

Jenkins, who ran as a Democratic Farmer Labor Party candidate, said the vision for Trans United Fund was initially "broad," but the goal was always to have a training mechanism for transgender and gender-nonconforming candidates.

Adhering to that mission, especially on the federal level, has proven difficult. And raising money for Trans United Fund hasn't been easy.

The costs associated with running and winning federal campaigns, coupled with the relatively small number of transgender candidates running for Congress, are reasons why Trans United Fund hasn't been active in federal races, Mora said.

Phillipe Cunningham, the first black transgender man elected to office in 2017.

Among Trans United Fund's victories at the local level came in 2017, when its non-federal PAC, Breakthrough Fund, spent more than $88,000 to counteract attacks leveled at Minneapolis City Council candidate Phillipe Cunningham, a transgender man. The Democratic Farmer Labor Party candidate narrowly defeated incumbent Barbara Johnson, who had occupied the seat for nearly 20 years.

Cunningham credits Trans United Fund -- it hired a consulting group to advise on tactics such as increased door-knocking and phone-banking efforts -- with helping him survive the last months of his campaign. Groups opposing Cunningham spent money on ads and mailers targeting his financial debts.

Aside from Trans United Fund, "everybody stayed out and nobody supported me," Cunningham said.

For Mora, Cunningham's triumph was a sign that his organization could make a difference.

But victory came with a cost. Trans United Fund has struggled to fully comply with state election laws, and it's incurred significant debt.

The debt is a result of a partner pledging $45,000 and then backing out. Mora said he had to appeal to the Trans United Fund board to assume the debt so the money could be used to help Jenkins' and Cunningham's campaigns.

This left Trans United Fund exactly $45,000 in the red -- debt it's since paid down to $18,578.61 as of July 31, according to Minnesota campaign finance records. But the situation may concern prospective donors.

While federal filings show Trans United Fund has raised no money at all for congressional elections, Minnesota campaign finance records show it received state-level contributions from Minneapolis-based individuals, local LGBTQ+ organization OutFront MN Action and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Minnesota State Council Political Fund.

Trans United Fund, which describes itself as nonpartisan, spent about $13,000 on three Democratic transgender women running for governor, U.S. House or state Senate in 2018. None of them won.

Meanwhile, according to IRS records, Trans United Fund's sister charitable nonprofit organization disclosed raising less than $50,000 for the 2016 tax year.

Most notably, the Trans United Fund has endorsed Roem. It also endorsed Jenkins, one of its co-founders, who won her 2017 Minneapolis City Council race with 73 percent of the vote. With her win, the City Council now has two black, transgender members out of 13 members overall.

Transgender political candidates are entering the broader political fold

Roem's race for a Virginia General Assembly delegate seat made her the highest-profile transgender political candidate in the United States, and arguably, U.S. history.

The race garnered national attention for its acrimony: Her opponent, Republican incumbent Robert Marshall, had previously called himself the state's "chief homophobe" and hurled insults at her throughout the campaign.

In September 2017, he declared that Roem and her candidacy were "against the laws of nature and nature's God."

Roem beat Marshall by more than 1,700 votes.

Although Marshall made Roem's identity a part of his platform -- he proudly touted his sponsorship of a so-called bathroom bill in Virginia that required transgender people to use bathrooms corresponding to their gender assigned at birth -- Roem had other priorities.

For Roem, the letter "T" didn't stand for "transgender" nearly as much as it did "transportation" -- she made improving Virginia's Route 28 highway a cornerstone of her campaign.

Roem told the Center for Public Integrity that she is defined by more than her gender identity. She said her years as a news reporter in Virginia gave her critical knowledge about public policy, which led her to focus on hyperlocal issues.

As a transgender elected leader, she said, her responsibility is to represent all the people who voted for her -- and even the ones who didn't.

Roem said groups such as Trans United Fund are needed to help transgender elected officials be perceived as viable candidates and public servants. The group contributed $5,000 to Roem's campaign committee in 2017.

She continues to work with the "burgeoning organization" as she runs for re-election. Just last December, Trans United Fund hosted a re-election event for Roem in Washington, D.C.

Mora said Trans United Fund didn't contribute more money to Roem because she was already receiving large sums of money from donors across the country -- Roem outspent her opponent by more than $539,000 -- and Trans United Fund wanted to focus its attention on helping the Minnesota City Council candidates, Jenkins and Cunningham.

Money troubles

Last year, transgender candidate Alexandra Chandler ran as a Democrat for a U.S. House seat in Massachusetts but lost in her primary.

Chandler was the only federal candidate Trans United Fund endorsed, mainly because of her stances on race, gender equality and immigration, Mora said. Trans United Fund also contributed $4,493 to her campaign, according to Federal Election Commission records.

But Trans United Fund erred in doing so: The money came from the group's nonprofit arm, not its political committee. Federal law prohibits nonprofits from making direct contributions to political candidates.

Mora acknowledged the error and says he's working with the FEC to resolve it. Erin Chlopak, director of finance strategy for the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center, said an error like Trans United Fund's is unusual.

"Most sophisticated PACs and entities are careful to not make that mistake," Chlopak said. Trans United Fund will most likely have to notify the campaign committee of its misreporting and the money will need to be returned. Trans United Fund could also face a fine from the FEC, but Chlopak predicted it would not be substantial.

Mora said Chandler has been notified and the money has been returned. A correction to the error will appear in Trans United Fund's next filing with the FEC, he said.

Chandler said she also received extensive candidate training from the LGBTQ Victory Institute, whose mission is to train and to elect LGBTQ+ leaders to office. But that preparation left her feeling burdened by the amount of money she needed to raise to run a successful campaign. The LGBTQ Victory Fund also skipped over her potential groundbreaking candidacy to instead endorse former U.S. Ambassador to Denmark Rufus Gifford, who is openly gay. Gifford and Chandler both lost in the primary.

Her campaign raised slightly more than $150,000 -- decent money, but much less than most winning congressional candidates.

The road to money and success isn't always smooth in politics -- particularly if you're a black, trans, progressive man, said Mora, speaking about Cunningham. "It's like David and Goliath," Mora said.

Public perceptions of transgender candidates

As transgender political candidates become more common, many Americans are still struggling to comprehend what being transgender means. Less than half of all Americans believe that gender can be different from what a person was assigned at birth, according to a Pew Research Center poll released last year. That division becomes even starker across party lines:

- 80 percent of those polled who leaned Republican said that gender is determined by sex at birth

- 64 percent of those polled who leaned Democratic said that gender can be different from sex at birth

Jenkins, of Trans United Fund, said transgender people and issues have often been on the edges of the larger LGBTQ+ movement.

"One of the mantras of the LGBTQ+ community, and I will say mostly LGB, is that, 'We're normal. We're just like you,'" she said, stressing gay men and lesbians have received more societal acceptance. "When trans-identified people come along, it sort of disrupts that narrative."

Andrew Reynolds, a political science professor at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill who's researched LGBTQ+ political candidates around the world, said that stigma around transgender people will fade in time. But "it's a very long game," Reynolds said.

That's a game Jenkins and Mora aren't willing to wait for as transgender people face legal restrictions -- along with the threats of assault, murder, suicide and homelessness.

"We have to step forward and stand up and fight for our rights and not wait for these other organizations to come to our rescue," Jenkins said.

Protesters outside the White House on October 22, 2018 at the 'We Won't Be Erased - Rally for Trans Rights,' in Washington, D.C.

Trump and transgender Americans

The urgency is prompted in part by the Trump administration's decisions affecting transgender Americans, which has alarmed transgender rights activists across the country.

But while campaigning for president, Trump signaled he supported transgender Americans and, similarly, wanted their support.

"Thank you to the LGBT community! I will fight for you while Hillary brings in more people that will threaten your freedoms and beliefs," Trump tweeted in June 2016, two days after a gunman murdered 49 people at Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

In his 2016 Republican National Convention speech, Trump said, "I will do everything in my power to protect our LGBTQ citizens from the violence and oppression of a hateful foreign ideology."

His campaign even sold a shirt that reads, "LGBTQ for Trump." It's still on sale on Trump's re-election campaign website, reduced in price from $30 to $24.

The White House and Trump's 2020 re-election campaign did not respond to requests for comment.

Although Trump has placed transgender identity in national discourse, his tactics of targeting LGBTQ+ individuals are nothing new to the federal government, according to Nicole Elias, a political science professor at the City University of New York.

"Trump is both more vocal and more restrictive of transgender rights in policies and programs compared to past administrations," Elias said, citing the Trump administration's proposal around gender and the transgender servicemember ban.

Why trans candidates need their own dedicated resources

Political groups that support LGBTQ+ candidates broadly have found great success in recent years, giving organizations such as Trans United Fund hope for growth.

The Human Rights Campaign, the nation's largest LGBTQ+ advocacy group, also has its own PAC, which has raised more than $1 million every election cycle since the mid-1990s. It raised $1.7 million last election cycle.

The LGBTQ Victory Fund PAC raised more than $826,000 this past election -- an election-cycle record for the group -- with two of its largest donors being Milwaukee businessman Christopher Abele and a super PAC called the Committee to Elect a Progressive Congress.

But these groups don't supplant the need for Trans United Fund, Jenkins said.

"It's like saying 'Does Black Entertainment Television need to exist? How come you just can't be on NBC?'" she said. "NBC is not playing the programming that we want to watch so we need to create our own."

Neither HRC nor LGBTQ Victory gave money to the nine transgender candidates who ran for Congress last year.

One notable donor to transgender candidates is watching Trans United Fund closely.

Amy Watt, a 32-year-old entrepreneur and former oil trader from Houston, spread $8,100 among several of the transgender federal candidates who ran last year, according to federal records.

Watt, a transgender woman, said she was motivated to donate by the so-called "bathroom bills" circulating in her state and wanted to combat this "symptom of maltreatment of transgender people."

Watt donated to Chandler, the transgender congressional candidate in Massachusetts, who put her in touch with the Trans United Fund.

Watt didn't donate to Trans United Fund. But she said she likes the idea of the group and wants to learn more about its organizational structure and governance before contributing.

What's next?

Mora said he'd like for Trans United Fund to continue to recruit and train "priority" candidates, or transgender people of color or people with immigrant backgrounds.

In January more than 1,000 people attended the Creating Change Conference in Detroit, which included a Trans United Fund-led candidate and campaign school for transgender, "queer and ally leaders."

Playing at the federal level still seems like a daunting task for Trans United Fund. Moreover, none of the current Democratic presidential candidates stand out to Trans United Fund, according to Mora, even though Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., pledged her solidarity with transgender Americans just last year.

Trans United Fund would like to partner with other emergent groups that have focused on multiple issues involving race, sex and immigration, like Mijente, Movement for Black Lives and UltraViolet. The goal would be for other organizations to include Trans United Fund's priority issues, such as race and gender equality and immigration reform in candidate questionnaires.

Trans United Fund will continue to endorse candidates who champion all the issues -- pro-trans, pro-black, pro-immigrant among them -- important to Trans United Fund, and it will mobilize volunteers as needed. Mora said there is interest in exploring how Trans United Fund can help Danielle VanHelsing, an independent candidate running for a Maine U.S. Senate seat.

For now, Trans United Fund is planning to tap transgender rights advocate and TransLatin@ Coalition founder Bamby Salcedo as a leader of its "social welfare" nonprofit arm. Trans United Fund is tapping black transgender rights advocate and founder of TAKE (Transgender Advocates Knowledgeable Empowering), Daroneshia Duncan, to lead its separate charitable nonprofit.

Transgender representation in office is not a large enough goal for Trans United Fund, Mora said. It wants to turn the tiny transgender voting population into a voting bloc to which lawmakers must answer. But exactly how it will accomplish its mission and be something different from other transgender-focused groups isn't completely clear.

"There's not a straight playbook," he said. "We haven't figured it all out."

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit investigative news organization based in Washington, D.C.