This essay was originally published in January 2016, shortly after Bowie's passing.

Like most children of the '80s, I first discovered David Bowie when he played Jareth the Goblin King in the 1986 Jim Henson film Labyrinth. It was, quite honestly, love at first sight. I watched that movie a hundred times, on what seemed like an endless loop, and every time I did I wondered, Who is this mysterious, strangely handsome figure casting spells and singing these weird, beautiful songs about magic and babies and worlds falling down? This was not your run-of-the-mill children's movie villain, and when I learned that the creature inside those captivatingly snug gray tights was the same guy behind the spunky radio hits "Modern Love" and "Let's Dance" (Mom really liked that one), I knew I needed to hear more. But I didn't know how; I was a boy, there was no Internet. So I just spent a good decade "down in the underground."

It wasn't until my last few years of high school that I became properly acquainted with Bowie the musician. I bought a pretty slim greatest-hits CD at the record store in my small town in upstate New York, and it soon became my go-to as I studied and wrote term papers in my father's home office. By then I'd heard the classics "Changes," "Young Americans," and "Rebel Rebel"--lovely and catchy enough to become some of my favorite "old-school" tunes--but exploring the other highlights from the first decade or so of Bowie's career was another story entirely.

The rest of the selections on that disc weren't what I expected. Tracks like "Starman," "Aladdin Sane," "Oh! You Pretty Things," and ""Life on Mars?" didn't sound like the "classic rock" I thought Bowie must have been creating in the 1960s and '70s. Unlike music by many of his contemporaries, these songs weren't aggressive or instantly engaging or easy to pin down. They didn't have self-indulgent guitar solos, nor were they selling formulaic accounts of love and loss. They felt legitimately old-school--full of theatrical pomp and bookish lyrics and late-night cabaret brooding--and yet also incredibly alien and forward-thinking. What human would write a bizarrely wondrous song like "Space Oddity" in 1969? Only one: David Bowie.

Meanwhile, the songs that did sound like what I had decided classic rock was--"Diamond Dogs," "John, I'm Only Dancing," "Rebel Rebel"--seemed way too louche and literary and, well, queer to make sense in any sort of mainstream setting. "You've got your mother in a whirl / She's not sure if you're a boy or a girl" went the opening lines of "Rebel Rebel." How, I thought, had he ever gotten away with such a thing? How did someone this eccentric and androgynous and uncompromising manage to become so insanely famous? My peers were looking back and gushing over McCartney, Lennon, Hendrix, Joplin, Morrison. I, the lonely, budding outsider homosexual who'd take fantasy over reality any day, had found my oddball idol. This was just the beginning; there was more beyond the hits. I had real homework to do.

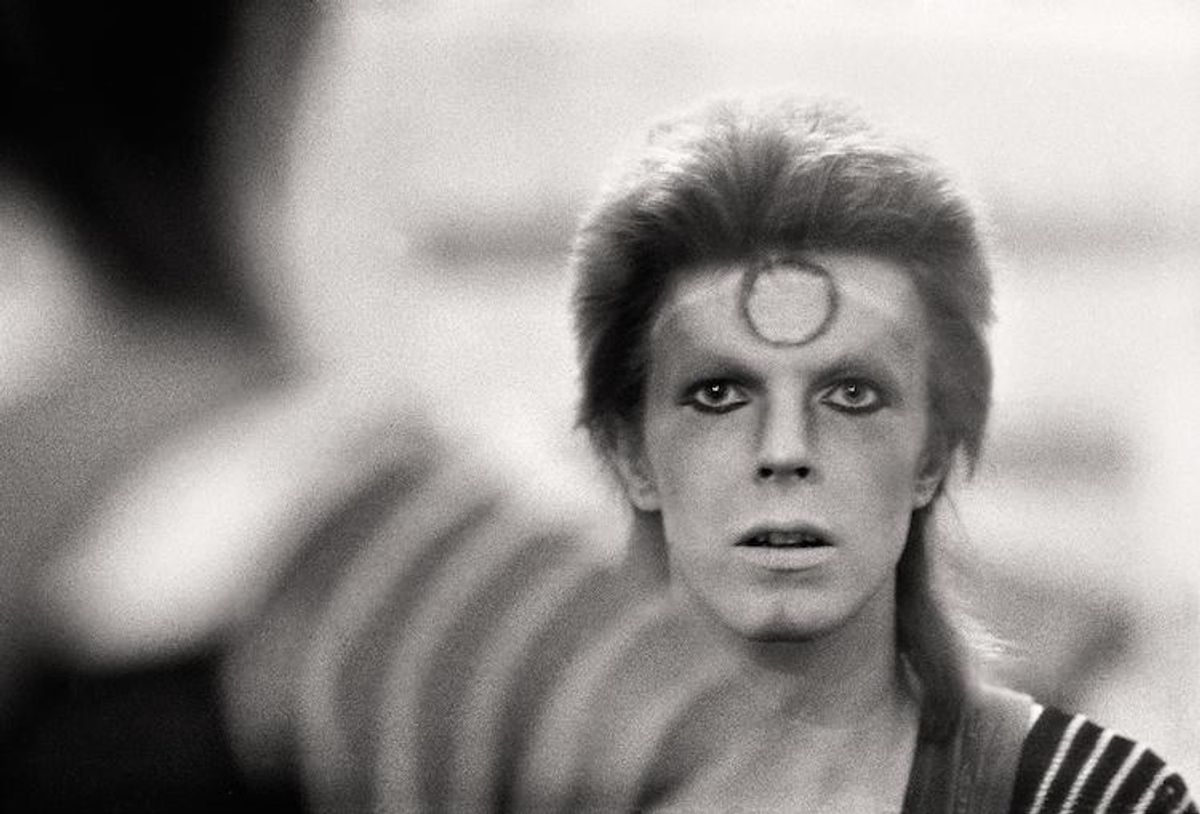

Photo by Steve Schapiro

Access was still an issue--I was a broke teenager, now with only a wonky AOL connection that made weird noises and that I only pretended to understand. While working alone during the evening shift at one of our local radio stations, where I changed music reels and played ads during timeouts in basketball games that the station aired, I found a copy of The Singles Collection, which feature twice (!) the number of songs as my Bowie disc. I played it during my downtime, sinking deeper and deeper into the complexities of the singer's catalog, and vowed that one night I'd just pilfer it. But I could never bring myself to do it for risk of getting fired. So I waited a bit longer.

Then came college, Napster download rabbit holes, grad school, and my falling head over heels for 2002's gorgeous, ethereal Heathen, arguably Bowie's best album since 1980's Scary Monsters. I was becoming more and more obsessed with hearing everything he'd ever done. I finished school and soon landed my first editor job at Out.

To this day, a highlight of my career was overseeing Out's 2008 list of "The Greatest, Gayest Albums of All Time," in which we polled more than 100 actors, musicians, writers, DJs, and label reps to determine history's most influential queer records. After tallying the votes, we revealed the album at the top spot: Bowie's 1972 genre-sweeping, gender-blurring opus, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (also on the list: 1971's Hunky Dory and 1974's Diamond Dogs). I was tasked with writing a short entry about the album--short, but of paramount importance in my mind. This was, after all, the most significant soundtrack of our queer lives. "You know he was singing for every exiled, dejected, sexually confused young kid who longed for a world of greater possibilities," I wrote of the album, trying my best to sum up the ineffable.

I spent hours and hours with all three of the albums that made that list, loving almost all of what I heard, promising myself I'd complete my mission to have absorbed Bowie's entire body of work, and within a few years I'd acquired used vinyl copies of almost every other major Bowie record: David Bowie/Space Oddity, Aladdin Sane, Pin Ups, Young Americans, Station to Station, Low, "Heroes," Lodger, Scary Monsters, Let's Dance. By then I also had Spotify to start filling in the gaps.

Last Friday, upon the release of his 25th album, Blackstar, which came out on Bowie's 69th birthday, I decided to revisit the legend's discography (most of which I'd now heard), including lives albums, soundtracks, and compilations. My goal: to pull together a list of some of my all-time favorite Bowie songs, from the well known to the more obscure. I spent the weekend listening to nothing but Bowie, reliving my childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood--and falling in love with him all over again. I ended my listening session Sunday night with the underrated gem "Thursday's Child," Bowie's 1999 brush with soft rock, a song about growing older but finding solace in the company of a loved one. My favorite line: "Maybe I'm born right out of my time / Breaking my life in two."

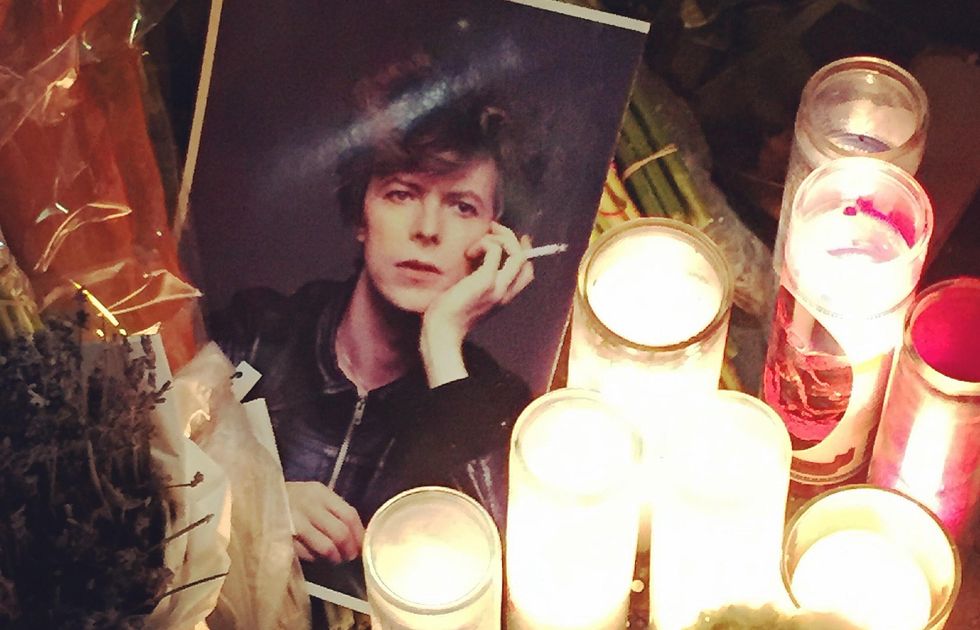

I awoke to the news of Bowie's death early Monday morning. Lying in bed, I devoured everything I could find about it online, including friends' and colleagues' posts about their shock and sorrow. In an effort to dull my pain, I played "Kooks," Bowie's baroque, buoyant ode to being proudly different. It helped, but only briefly. I spent the next four hours in my apartment, afraid to leave it and face the light of day, afraid I wouldn't be able to ride in a subway packed with grievers or order my coffee without crying. I played one of my absolute favorite Bowie songs, Ziggy's opening track, "Five Years"--in which the narrator learns that the world is ending--on repeat for half an hour. It felt appropriate, bittersweet.

It's been a difficult, devastating week, one of private and public mourning. We've witnessed an outpouring of love from fans and superfans. According to Vevo, Bowie's videos were viewed more than 51 million times in a 24-hour period on January 11, beating a record previously held by Adele. Bowie albums currently occupy 15 of the top 25 albums on the iTunes Charts. Critics have weighed in. Musicians--from Iggy Pop to Arcade Fire to Michael Stipe to Lorde--have shared their stories and expressed their deep gratitude to the artist.

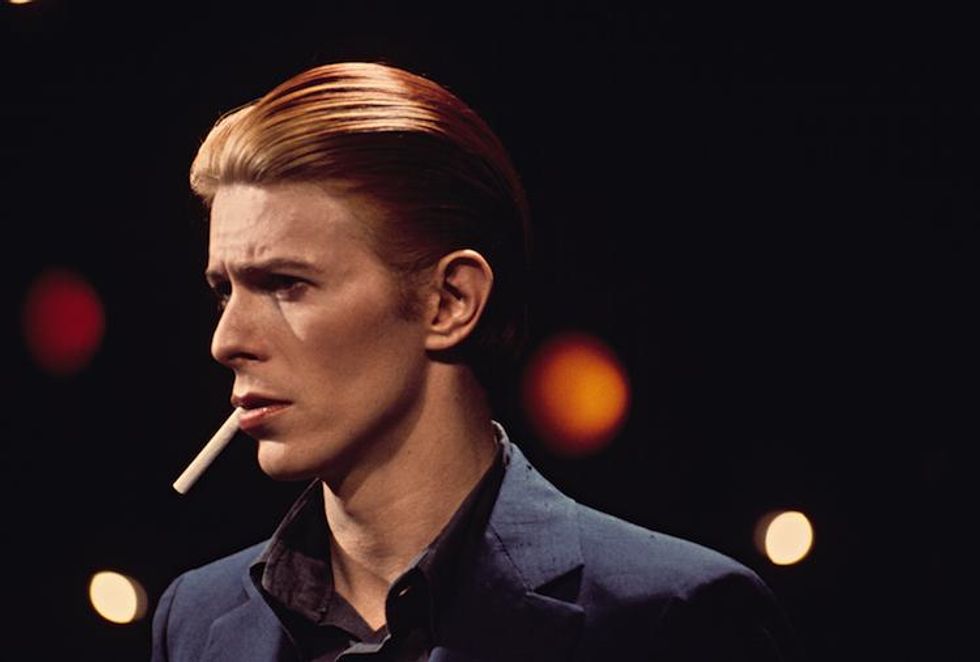

Photo by Andres Giusto

Bowie, the person, is gone. All that's left is the music. The various personas--Ziggy, Aladdin, the Thin White Duke, Jareth. The glorious saxophone solos. The ambient masterpieces. The poetic lyrics to pore over for years to come. But at this point, for me at least, talking about Bowie's music, which spans an astonishing five decades, feels like talking about air. How do you describe something that's just always been a part of your life, something you know you can't live without or ever really grasp?

"I can't give everything away," Bowie sings on the closing track of his dark and exquisite new album, Blackstar, which we now know was the icon's last gift to us. And yet it feels like he gave us everything we could have ever wanted from a pop star--the myth, the mystery, the endless surprises, the costumes, the heart, the soul.

After learning of his death, I knew I needed to continue working my way through Bowie's oeuvre and finish my list right away. So here it is. Some of these songs are hits, some are B-sides, some are old, some are from the past 10 years. Some are glam rock, some are disco, some are funk, some rank among the most poignant ballads ever written. Some will make you sad, some will make you want to explode with joy. They represent only some of my favorites, but every last one of them is excellent. There are 69 songs here, one for every year Bowie inhabited this earth, a world he was always greater than but nonetheless changed forever.

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays