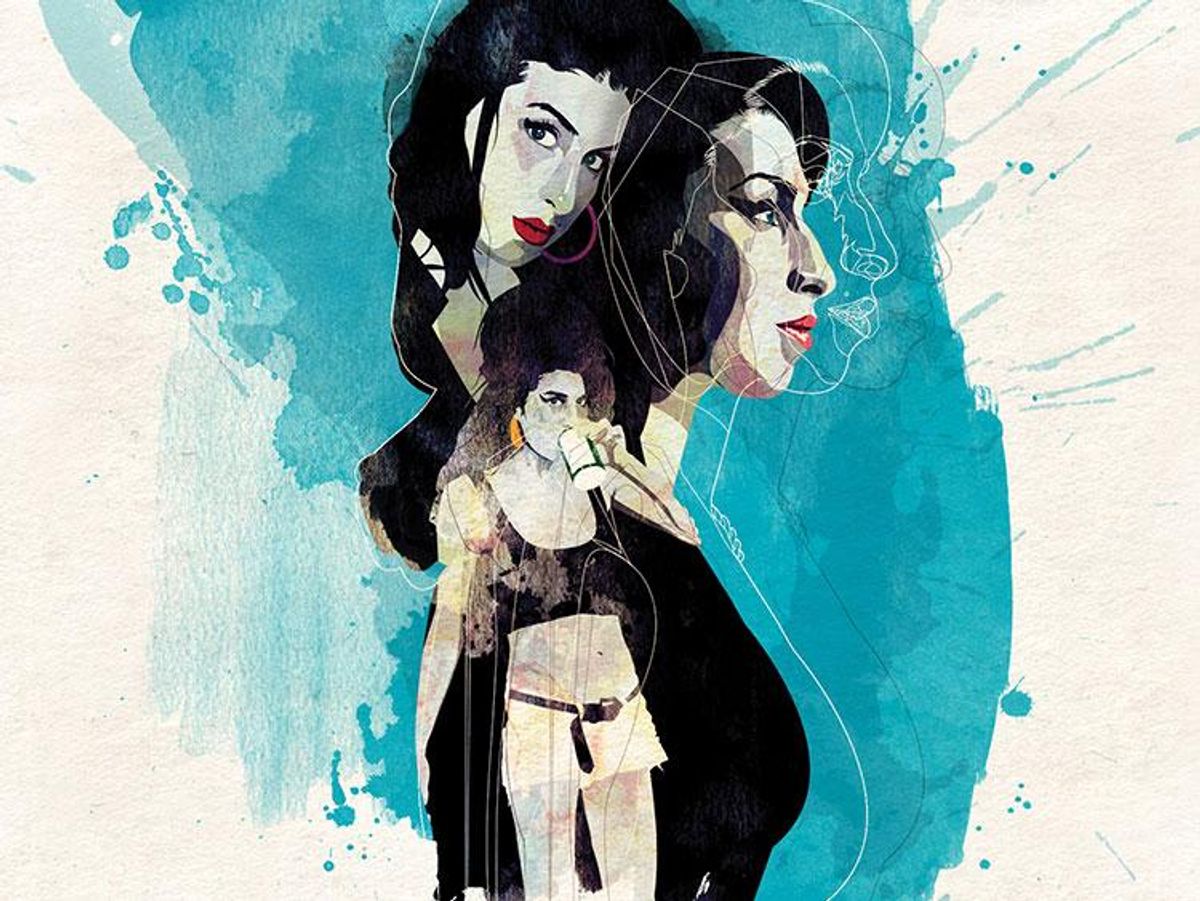

Illustration By Alvaro Tapia Hidalgo

I found my idol -- too late to do anything about it -- on an exhausting transatlantic flight to Norway. It was a brand-new carrier, so I struggled to stay awake in order to play with the high-tech video screen. When I clicked halfheartedly on a picture of a young woman with a '60s-girl-group hairdo, I found myself watching Asif Kapadia's Oscar-nominated documentary Amy. By the end of it, I was stunned. I fancy myself as something of a music lover, and couldn't understand why I hadn't been more aware of Winehouse while she was alive. At a time when the last big individualistic diva voices of soul and R&B -- women like Aretha, Whitney, or Mariah -- were fading, Winehouse's contralto voice was gushing across the airwaves in a fascinating melding of jazz, soul, R&B, and reggae -- proof that heavy sound engineering isn't the only way left to make a hit. With her lyrics, she had pushed the boundaries of the frankly sexual and embarrassingly personal. As soon as I got back to New York, I listened to all three of her albums. Somehow it wasn't enough. Little did I then understand that the music marketers and scandalmongers telling Amy's story had made it as hard to extract as a diamond dropped into a sewer.

The real Amy Winehouse existed parallel to the shameful media blitz leading to her demise. She was a fourth-generation Jewish girl from North London, and her father, Mitch, and grandfather, like many other British Jews from lower-middle-class backgrounds, were taxi drivers. Despite the girl-group look she adopted later, the party lifestyle she took too far, and the marriage to an addict that led her deeper into drugs, she never really forgot her true identity, and maintained close family ties. By the time she was born, her father had already managed to move his family from London's poor East End, where his grandfather ran a barbershop, and settled them in a more upscale northern suburb, Southgate. But the family was still in the habit of coming together every Friday night for a traditional Sabbath dinner, and Amy would attend her share of Passover celebrations and High Holy Day rituals. Just two days before she died after a prolonged struggle with bulimia and alcoholism in 2011, Amy spent an afternoon going through a newly discovered cache of family photos, urging her father to rush over to her $3 million Camden flat and enjoy them with her.

Relics of the family gatherings, as well as hundreds of other photos of the life she had lived as a typical Jewish girl, remained unseen until 2013, when London's Jewish Museum organized an exhibition of personal effects curated by her brother and sister-in-law. One could see Amy at her brother's bar mitzvah or in her grandmother's house wearing the long white socks (pulled halfway up her legs) and blue cap of the Jewish Lads' and Girls' Brigade. Her brother, Alex, summed up her identity in a caption he wrote for one of those photos: "This is a snapshot of a girl who was, to her deepest core, simply a little Jewish kid from North London with a big talent, who, more than anything else, just wanted to be true to her heritage."

It was her dad Mitch's rich collection of retro music tapes, used to while away his working hours, that launched daughter Amy on her path to fame. From the time she could walk, Amy joined her "Da'" in crooning along with Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Otis Redding, Motown artists, and gospel. Whatever charges can be brought against her father -- whom Kapadia, in his documentary, burdens in part with responsibility for her descent into addiction -- her close ties to him were not only emotional, but creatively influential, helping to shape her aesthetic. That influence never went away. Already a reigning pop star when she recorded her sophomore album, Black to Black, in 2006, she still had the habit of slapping the newly minted songs on a CD and dashing outside to see how they sounded in her father's taxi.

Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, and Dinah Washington were firmly seated in Amy's musical orbit as a pre-teen when she moved on to devour her brother's Thelonius Monk collection, and spent three obsessive months listening to Ray Charles. Just a couple of years later, she and best friend Juliette Ashby became enamored of the feisty, frankly sexual Salt-N-Pepa and formed their own hip-hop group, Sweet 'n' Sour. You can guess which of the pair Amy was. "We had two little boys to be our little bitches who would dance for us," she later boasted to an interviewer.

Frank, Winehouse's debut album, was released in 2003 when she was 20 and largely unknown. Named for her dad's idol, Sinatra, it quickly rose in the U.K. charts, boosted by word of mouth. But although her distinctive phrasing and astonishing lyricism marked her out from the crowd, she was still miles away from mastering the art of stage presence. In fact, the "little Jewish kid from North London with a big talent" was still not above picking at her nostril onstage as she sang or flicking something from between her teeth during an interview. Slightly plump and packed into a skintight budget dress, tottering on much-too-high spike heels, she expressed a certain lackadaisical attitude toward the whole performance game. Her guitar technique might have been rudimentary, but her opinions about her fellow singers were squarely in place. She didn't even attempt to stifle a yawn when an interviewer compared her to Dido, whose music she dismissed as "background music, the background to death."

Although Amy's jazz and soul singing quickly became beyond reproach, a few supercilious gatekeepers still sometimes pointed fingers at vestiges of the amateurish, and of the "pushy" Jewish kid. In a review of a 2004 concert she gave at the Jazz Cafe, music critic Neil McCormick called her, "the girl with everything -- except stage presence." The popular British TV host Jonathan Ross, himself once charged with coarsening the British airways, calmly dissed her on his talk show with a backhanded compliment: "You know what I like about you? The way you sound so common."

What had become immediately apparent besides her "common" girl's flair for '60s soul and jazz standards was the fact that she was a phenomenal lyricist. Disastrous love affairs and depressing family conflicts popped into songs of stunning frankness. In her masterpiece "What Is It About Men," she exhibits an uncanny grasp of the psychoanalytical dynamics of her family, helplessly confessing, "I can't help but demonstrate my Freudian fate." Although her father believed his affair with a woman at work that began when Amy was 18 months, and climaxed with divorce when she was 10, had barely ruffled her, "What Is It About Men" tells another story. What Dad did is "bricked up in my head / it's shoved under my bed," and is the reason why she keeps replaying the losing game of love with all her own boyfriends. In the ingeniously reductive "Take the Box," Amy sums up a failed relationship by ordering the man she is leaving to give back two symbols of their past happiness -- a gift and a Frank Sinatra album: "The Moschino bra you bought me last Christmas / Put it in the box, put it in the box / Frank's in there and I don't care / Put it in the box.... / Just take it." In "Stronger Than Me," she devalues the sensitivity that many other young women would love to find in a man, by slamming him with the complaint, "You always wanna talk it through -- I don't care / I always have to comfort you when I'm there," then further denigrates his conventional approach to courting by barking, "I'm not gonna meet your mother anytime / I just wanna grip your body over mine."

Amy's bitchy, brilliant lyrics, and her mastery of both contemporary and retro genres, had brought her to full ascendancy with her second album, Back to Black. Less than a year later, in 2007, everybody wanted a piece. That February she won Best Female Solo Artist at the Brit Awards. A little more than a month later, Back to Black reached number 7 on the Billboard chart. By then, although she still had problems controlling her legs, her stage presence had become more professional. The enormous beehive hair, Cleopatra eyes, and sex-kitten dresses created an indelible image. Amy could do soul, jazz, and hip-hop, and the songs she wrote were widely admired. But she was also living, and quite soon, dying, proof that no one is finally strong enough to withstand the packaging power of the pop machine.

From the very beginning, she had stubbornly tried to control her recording sessions. Frank, produced mainly by Salaam Remi, is probably the least electronically processed, and as close as she would ever come to recording things her way. Most of the songs are influenced by jazz, a genre she saw as her purest, and all, except two covers, are written or co-written by her. But she would later complain that even that experience had left her "only 80% behind the album" because Island Records had ignored her preferences regarding the songs and mixes to be included.

Unlike many of today's pop artists who are more than happy to be bolstered by electronic and orchestral effects, Amy was at heart a purist. "I probably earned a reputation as a difficult person because I wrote my own songs and I didn't need people in the studio with me," she told an interviewer. "Not to be rude, but these people would be trying to write pop songs! And I would say, 'Who are you writing for? What session are you on? Get out.' " When producer Mark Ronson tried speeding up her hit "Rehab" and adding his own drums, Amy put her foot down, complaining, "Are you trying to make me sound like the bloody Libertines?"

She hated strings in her arrangements, but that was a "losing game" as well. Despite her telling a recording engineer, "If you want to work with me and you love strings, then go home," the strings crept in until her music sounded the way the industry wanted. Mix engineer Tom Elmhirst manipulated the '60s soul vibe of "Rehab," so that, as he pointed out, "it would work for radio without losing any of its charm." Elmhirst may have admitted that Amy was "a very dynamic singer" and had "a lot of bite in her voice," but he wanted to "notch out specific frequencies." His problem was with the harsher tonal qualities, the very qualities that went a long way to distinguish her from the pack. Elmhirst wanted that voice to "sound warm and not take your head off." So he used an equalizer to remove sibilance.

Amy Winehouse may in fact be the last "voice" in pop music. Nearly all the rest are buried in layers of studio engineering. Yet anyone who wants to see Amy at her peak will have to comb through the welter of YouTube performances from every period, from her earliest and most primitive to the tragically erratic apparition near the end, when she can barely stand on her matchstick legs. Somewhere between the plump North London Jewish girl and the skeletal victim are breathtaking stylizations of her own songs and stunning reprisals of past hits. The very best may be her live cover performance of Donny Hathaway's "I Love You More Then You'll Ever Know."

89-year-old trouper Tony Bennett recorded duets with other pop singers like Lady Gaga to beef up his sales, but Amy Winehouse was the musician he compared to Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday, after they recorded a duet of "Body and Soul" in March 2011. In Kapadia's Amy, he recalls that he could both see her extraordinary talent and anticipate her coming danger. Yet as Amy stood in the recording studio with her idol, she still had lots of plans for the future, including recording a purist jazz album and studying how to play instruments. She wanted children, too, if only to tell grandchildren someday the story of recording with the great Tony Bennett. She was dead four months later.

Additional research by Cathleen Peters

Like what you see here? Subscribe and be the first to receive the latest issue of OUT. Subscribe to print here and receive a complimentary digital subscription.