"Hello, Papi, I am in Brazil."

A text message I received sitting in my home office after nearly a month of silence signified Victor Arellano's nine-month battle had just been won. Arellano escaped Venezuela with a bullet in his spine, fleeing across violent and treacherous terrains, to have a chance of survival in a place providing no guarantees of a better life.

Early last year, when the pandemic first began its lethal assault upon the world, Arellano, a 30-year-old gay man, was walking home from a friend's at dusk. He was shot point-blank in the face and was left with a bullet lodged between the joints of his cervical spine that missed his spinal cord by only millimeters.

"What do you mean, three men?" I asked Victor in broken Spanish at the time.

"Three men started beating me and calling me a f****t," he replies. "I tried to fight them off, but I just couldn't. Then everything went black."

In the police report from the night of Arellano's attempted murder, two witnesses reported hearing gunshots and seeing three men running out of Arellano's home with his motorcycle and several other personal possessions. Arellano says local police, with little funding and few resources, told him they are unable to follow up and are unlikely to do so in the future.

Jesus Gomez, a gay Venezuelan refugee living in Cucuta, Colombia, sits down after a long day at the hospital where he is currently training to be a nurse.

Murder is a common occurrence in Venezuela. In fact, 16,500 homicides were reported in 2019, and its murder rate was the highest in Latin America -- 60.3 violent deaths per 100,000 people, according to the U.S. State Department. But in the Hernandez Tachira Parish, a quiet evangelical community where Arellano lived and was shot, violence is not a common part of the local narrative. Quiteria Franco, a spokesperson for Union Afirmativa, an organization fighting for LGBTQ+ equality in Venezuela, believes Arellano was "targeted based on his sexuality." A GoFundMe page has since been created to help Arellano's hospital bills following the attack.

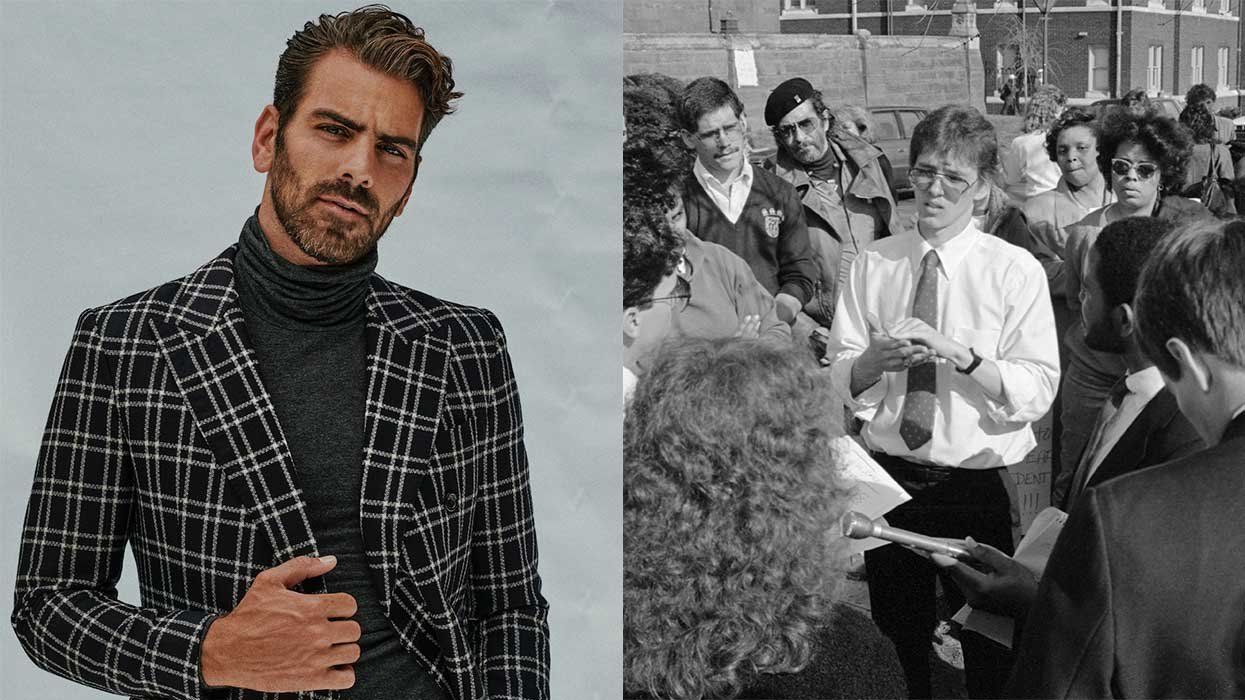

Venezuela once led the charge for LGBTQ+ acceptance in Latin America. The nation formally banned discrimination based on sexual orientation in 2012, although protections had existed in some form since 1996. In May 2016, the National Assembly unanimously approved a resolution establishing May 17 as the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia. But it was suspended a month later by Venezuela's Supreme Court, which had been stacked by Hugo Chavez, president from 1999 until his death in 2013. This was the first of many blocked resolutions for LGBTQ+ equality, including marriage rights.

Over the next few years, Venezuela deteriorated into a nation where, according to a source in the Venezuelan government who wishes to remain anonymous, at least 25,000 extrajudicial killings took place in 2019, and some of the victims have been high-profile members of the LGBTQ+ community. These people are killed for simply speaking out against their government, the same source said. Arellano is among thousands of LGBTQ+ Venezuelans who have been forced to flee due to violence, extreme poverty, and a lack of access to basic necessities such as housing, food, and medical care. As these conditions continue, a staggering 16 percent of all Venezuelans have left the nation since 2015, according to a Brookings Institution report. As of February, nearly 5.5 million Venezuelans were living outside the country, making it the largest recorded refugee crisis in the Americas.

The country's spiral into one of the world's most dire humanitarian disasters is "likened to bringing frogs to boil," explains National Assembly member Tamara Adrian, the first transgender woman elected to office in Venezuela, when asked how the crisis began. "The story of Venezuela is found in the oil."

In the early 2000s, under the Chavez administration, the price of oil, Venezuela's only export, reached $140 per barrel, allowing Chavez's Marxist-Leninist government to expand social supports for Venezuela's poor. Chavez believed that the price of oil would continue to go up, but the reality was quite different. In fact, oil prices inverted while Chavez's government continued expanding Venezuela's social services while failing to invest in oil infrastructure and leaving the country deeply in debt.

Today's Venezuela, once the wealthiest country in Latin America, remains the most oil-rich country in the world and yet extracts below 1 million barrels a day as opposed to the 3 million barrels it was extracting daily at the peak in the late 1990s. With over half of the money earned from oil being used to pay back the country's debt, Venezuela's spending continues and its economy is declining, and while inflation has eased a bit, it remains high.

Michell Lopez, Estrella Fuentes, Ruby Diaz, and Michelle Quiroz stand at the center of the Simon Bolivar International Bridge on the Venezuela-Colombia border.

Political machinations have only worsened the humanitarian crisis for Venezuelans. Nicolas Maduro, who became president upon Chavez's death in 2013, has exercised dictatorial powers. He won reelection in 2018, but there were reports of widespread fraud, and many countries, including the U.S., recognized National Assembly head Juan Guaido, a leader of the opposition to Maduro, as the nation's interim president. The actions of other countries had little effect within Venezuela, however, as Maduro has remained in office and has severed nearly all diplomatic relationships, leading to wide-ranging sanctions from the United States and its allies. With these sanctions, inflation, and a lack of infrastructure and jobs, many Venezuelans are starving and going without basic necessities.

"Look at extreme poverty numbers! People are forced to give up their children because they simply can't afford to feed them," Adrian says. "Animals are dying. People are forced to eat garbage. It's an incredibly dire situation."

As the economy of Venezuela crumbles, reports from the United Nations Human Rights Council revealed that nearly 96 percent of Venezuelans live in poverty and 70 percent live in severe poverty, meaning that most Venezuelans live on less than $1.90 per person per day, that being the international poverty benchmark. According to various monitoring groups inside Venezuela, violence and hunger have become widespread. Food shortages have reached new heights in recent months, leaving 80 percent of Venezuelan households without sufficient access to food. Grocery store shelves have remained bare, and hospitals are struggling to treat severely malnourished children. These realities, combined with the collapse of the country's public health system, are leaving many without access to lifesaving medicine and are making the survival of other queer people in Arellano's situation nothing short of a miracle.

"Life is better outside of Venezuela," Arellano says now, referring to countries that many LGBTQ+ Venezuelans escape to like Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. However, Arellano's idea of life outside of Venezuela is becoming less and less true. As countries throughout Latin America deal with the devastating economic impacts of the ongoing global pandemic, many are introduced to a bleaker reality. Vulnerable populations are subject to exploitation by criminals, further eclipsing their cherished dreams of freedom. Many migrants are forced into the dangers of living on the streets in foreign countries. Meanwhile, as the Venezuelan population is reduced, outcomes have become dire and are opening a wider door to violence than what was previously found in the country.

The hospital where Arellano was born and his life was saved 30 years later is now without medicine and nurses. And just as he was being given a new chance at life, Michell Lopez, a transgender Venezuelan migrant, was rapidly fading away.

In the valley of the Colombian Andes, on the Venezuela-Colombia border, sits Cucuta, a city with a history of violence. It now provides a safe harbor for organized crime networks that facilitate the region's cocaine trade and is home to thousands of Venezuelan migrants. It is also where Lopez works in the streets every night selling her body to survive.

Cucuta's commercial district, where many trans women like Michell Lopez resort to sex work in order to survive.

Lopez, the oldest of a family of six, arrived in Cucuta in 2017 after being held in a prison for two years for stealing food for her starving family. Upon first glance, you instantly see Lopez's glamour and the fearless confidence that comes with it. But upon closer inspection, a different story emerges.

"This is Officer Estrella, Officer Costeno, Officer Diaz," Lopez says, pointing at scars all over her body while we walk through the streets she works. "It's the names of the people who gave me these scars."

"This is the place where the police stole my phone," she continues as we turn the corner of a busy square at the center of Cucuta's commercial district. When asked what effect the trauma had on her business, she replies, "Who wants to fuck a beaten hooker?"

Disturbing pictures of Lopez's beaten body began to surface the night after she alleges police physically assaulted her, days before my arrival in Cucuta. Other sex workers I spoke to in the area claim Lopez confronted police while they were bullying a young disabled person selling candy in the square where Lopez was working that night. When asked to comment about the incident, law enforcement said protection of Venezuelan migrants is a top priority in Cucuta and that it was likely that security guards were responsible for the beating. They added that due to a lack of evidence, they were unable to pursue any charges.

"They beat her with a stick," says Michelle Quiroz, a trans migrant sex worker who reports she was present during the assault. "It happens all the time to Venezuelan trans [people]."

Colombians are growing increasingly weary of Venezuela's protracted crisis, which has led to increases in xenophobia and transphobia across the already fractured country, according to Oxford University's CONPEACE policy research center. This has been linked to a rise in reports of violence against Venezuelans, especially in cities close to the Venezuelan border such as Cucuta. The region has even seen the rise of one Colombian paramilitary group called Aguilas Negras (Black Eagles) that has threatened to kill all Venezuelans. Still, the situation has not deterred Venezuelans from entering Colombia in mass numbers.

Estrella Fuentes stands at La Trocha, a dangerous and illegal path beneath the Simon Bolivar International Bridge at the Venezuela-Colombia border. Hundreds of Venezuelans risk their lives every year by crossing La Trocha, an area that is heavily protected by police force.

Many of the migrants coming to Colombia cross the Simon Bolivar International Bridge, one of seven legal entry points at the Colombia-Venezuela border. Before the pandemic, an average of 30,000 people crossed the bridge daily. It is a few blocks away from where I met Lopez and Quiroz for the first time, three weeks before Lopez's alleged assault by police. The day I met them, they were serving Venezuelan families with little access to food at a local nongovernmental organization called Fundacion Venezolanos en Cucuta (FUNVECUC), just a short walk from the bridge. The organization was founded by Eduardo Espinel to assist Venezuelan migrants in vulnerable situations, offering guidance, counseling, legal services, and medical support at the sometimes-violent border.

As I walked through the gates of FUNVECUC, I met my interpreter and now friend, the organization's doctor, Arjenis Mena. Forced to send his children thousands of miles away into the United States and New Zealand to keep them safe, Mena stayed behind to care for his countrymen. Lider and Mena are now exiled from Venezuela but remain at the border even at the peril of their own lives to continue helping thousands of migrants.

At FUNVECUC, migrants lined up at the gate to eat the delicious food served by Lopez, Quiroz, and other members of the trans community. The atmosphere was surprisingly cheerful and full of laughter as music played in the background while Lopez and Quiroz danced and sang with children and other volunteers.

"I feel safe when I am here," a tired Lopez says while taking off the apron she wore serving lunch to nearly 1,000 people that day.

Michelle Quiroz (top) sits in Cucuta's town square, an area she works at night. Maria Angulo (bottom) is one of many queer Venezuelans speaking out for LGBTQ+ rights.

The relationship between violence and the transgender community is a story told around the world, as abuse by police, clients, and intimate partners is reported daily. Furthermore, transgender people all too often experience family rejection as well as discrimination in education, employment, and other aspects of life. This results in higher rates of unemployment, poverty, housing insecurity, and further marginalization, especially for those who are forced to migrate.

"I was diagnosed with HIV in May," says Dixon Ramirez, a software engineer who has now turned to selling on the black market. He sits with trepidation in the conference room of Dialogo Diverso, an Ecuadorian grassroots organization, which is adorned with rainbow flags. "I came here for assistance."

Dialogo Diverso sits 30 minutes from the Equator and is the only organization in Ecuador that serves the LGBTQ+ Venezuelan migrant population. Many consider it a home away from home. It was started around a kitchen table and has now grown to serve thousands of LGBTQ+ Venezuelan migrants all over Ecuador.

"We work with several members of the Venezuelan HIV community," says Danilo Manzano, its young executive director and cofounder. "Many come to Ecuador not even knowing that they are HIV-positive because of the lack of testing in Venezuela."

HIV testing is extremely limited in Venezuela and only exists in private clinics, costing nearly a year's salary to get. Without comprehensive testing, it is estimated that approximately 300,000 people are living with HIV in Venezuela. Access to lifesaving antiretroviral drugs is nearly nonexistent. Complicating matters, it has been reported by several news organizations that members of the Maduro regime have been harassing humanitarian organizations that provide HIV medication, limiting their ability to provide the treatments their clients need while disproportionately impacting members of the LGBTQ+ community. Without these medications, Venezuelans living with HIV are faced with the stark choice of leaving or dying.

Many Venezuelans living with HIV migrate to Latin American countries like Ecuador to access state-funded medication and treatment programs. But these countries do not always have the capacity to serve the growing number of migrants. Since the pandemic began, Venezuelan migrants living with HIV are faced with more challenges. With a loss of livelihood, many are evicted, and with a lack of stable housing, many find themselves in irregular living situations and without documentation. Often these compounding issues sever access to their host nation's health care and welfare programs, creating an even greater hardship. Many are left with no options and are forced back to Venezuela.

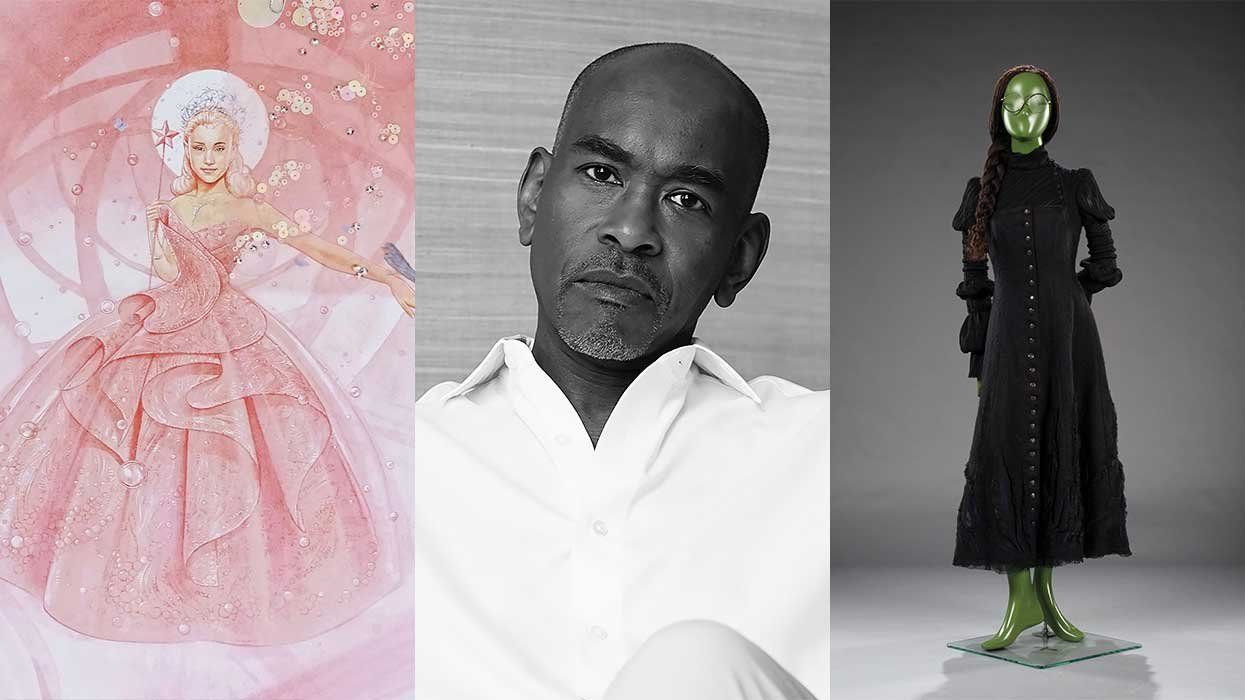

Jesus Aguais, a Venezuelan HIV activist, is now executive director of Aid for AIDS in New York City. Aguais's organization "works to provide HIV medications to people in Venezuela who do not have them," he explains.

Jesus Aguais and his son in New York City.

Aguais founded Aid for AIDS in 1996 while working at the HIV Clinic at St. Vincent's Hospital in NYC. He had noticed that many patients who changed treatment regimens would discard the unused medication left from their previous treatment. Aguais had the foresight to urge his friends and clients to pass on their leftover medication to him. After meeting an elderly woman who had sold all of her possessions to come to the U.S. in an effort to get treatment for her family in Venezuela, he realized the medications he had been saving were the ones this woman needed for her family. That one interaction inspired Aguais to create Aid for AIDS, which has grown to be the largest medication recycling organization in the world, helping thousands worldwide.

Aguais is not alone, as many organizations throughout the world work tirelessly to support the LGBTQ+ global diaspora, like HIAS (originally founded as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society).

"HIAS is the reason I survived," Arellano explains while recounting his escape to Brazil. The organization provided Arellano with lifesaving antibiotics and food weeks after his hospitalization. Established over a century ago, HIAS has helped migrants and refugees like Arellano across the globe. Recently, HIAS opened an office in Peru to help address the humanitarian crisis emerging with Venezuelan refugees.

"I was freer to be gay in Venezuela," Enmanuel Perez, one of HIAS's new social workers, explains of living in Peru, where homophobia can be worse than at home. Standing over six feet tall with tattoos adorning his body, Perez (pictured below) appears threatening at first, but everyone soon learns he is quite the opposite. "I was a lawyer in Venezuela," he explains. "Police take advantage of the fact that many Venezuelans do not know what their rights are."

This was made abundantly clear when watching Perez work with a young gay Venezuelan migrant who had come to HIAS after being physically assaulted by his Peruvian boyfriend. "Many of our LGBTQ+ clients do not realize they have the right to report abuse to the authorities," Perez says. "Unfortunately, many police in Peru are homophobic and threaten members of the Venezuelan LGBTQ+ community with deportation if they report abuse."

Peru is listed as a moderate threat to LGBTQ+ people in the Periodic Risk Intelligence and Security Monitor annual report for 2019. Furthermore, in a devastatingly revealing, first-of-its-kind study conducted in 2017 by Peru's National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, 63 percent of the 12,026 LGBTQ+ people surveyed reported experiencing violence or discrimination. Only 5 percent reported that violence to authorities. The study reveals that beatings, eviction, and loss of employment, especially among LGBTQ+ migrants, are a regular occurrence.

With Peru now becoming host to over 1 million Venezuelan refugees, second only to Colombia, HIAS has been forced to increase its services rapidly.

"We are now serving 50 to 80 clients a day," says pink-haired Erika Alfageme, HIAS's country director for Peru. "A crisis that started as a trickle has now progressed into a flood that no government or country was ready for."

While Alfageme fails to mention what role the United States has played in the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis, a history of U.S.-fueled war in the region in the 1990s has set the stage for a hands-off approach to the growing problem.

From 1898 to 1994, the United States participated directly or indirectly in 41 regime changes throughout Latin America, according an article by John Coatsworth, a historian specializing in the region, published in the Harvard Review of Latin America. The motivation was usually to support conservative and anti-Communist regimes. U.S.-supported corrupt oligarchs have now ruled for decades and shown little interest in improving the lives of the poor, worsening the refugee crisis.

The U.S. has continued its tough sanctions against Venezuela but has not taken a leading role in relief efforts. Thus Venezuela has found a partner in Russia and forged a new economic and political partnership that has served to place an even greater wedge between the U.S. and Venezuela. Even though the U.S. has provided $1.2 billion in assistance to Venezuelans inside and outside the nation since 2017, the Venezuelan refugee crisis is still the largest and most underfunded refugee crisis in modern history.

For members of the LGBTQ+ community who seek asylum in the U.S., life can be far worse than in certain parts of Latin America. Nearly 30,000 Venezuelans applied for asylum in the U.S. in 2017 and an equal number in 2018, beating China as the number 1 source of asylum seekers. Only 50 percent of those who applied for asylum were approved, forcing many into the world's largest private prison system: Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention centers.

New York City's Central Park with Gustavo Acosta, Yonatan Matheus, Wendell Oviedo, Jesus Aguias and his son Daniel, Tibisay Castaneda, and Katerine Pileggi. The group makes up only some of the city's LGBTQ+ Venezuelan diaspora.

There are approximately 289,700 undocumented LGBTQ+ immigrants in the U.S., according to the Williams Institute, a think tank at the University of California, Los Angeles. It's been estimated that 15,000 to 50,000 of these are transgender. Undocumented transgender people face a high risk of discrimination in employment, housing, and health care, in addition to violence -- 44 transgender people were killed in the U.S. in 2020 alone. Without the quick rollback of Trump-era policies, the trans community will continue to suffer worldwide.

"They masturbated themselves in an effort to excite me ... at all times of the day," Gustavo Acosta, a gay Venezuelan migrant who is currently out on bail from ICE detention, tells Out. Acosta goes on to claim he experienced 13 months of sexual harassment and abuse while in ICE custody. Sadly, his story is not unusual.

In a March 2019 letter to ICE, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center, and the Santa Fe Dreamers Project said 12 gay and transgender detainees in the Otero County Processing Center in New Mexico were regularly sexually harassed and abused. The letter further alleged that many of the detainees were placed in solitary confinement after reporting the abuse.

During Donald Trump's administration, an already fractured immigration system was turned into the acting arm of American xenophobia, destroying in its wake already fragile lives. Most of those enduring the greatest burden of this xenophobia are from the global south -- most notably Venezuela.

Yonatan Matheus and Wendell Oviedo (top) fled Venezuela for a better life, which they now share together in their New York City apartment. Tibisay Castaneda and Katerine Pileggi escaped Venezuela together and are using their love story to help LGBTQ+ migrants find their own road to freedom.

While the Trump administration plotted to overthrow the Venezuelan government, the administration was secretly deporting Venezuelans back to the country, and many of these people were members of the LGBTQ+ community. President Joe Biden's administration, however, announced in March that it would grant temporary protective status to the estimated 320,000 Venezuelans under threat of deportation, enabling them to work legally in the U.S. for the next 18 months as the Biden administration considers further moves regarding the crisis.

As the largest single donor to the crisis response in Venezuela and the region, the United States has provided more than $1.2 billion, in humanitarian, economic, development, and health assistance for Venezuelan refugees and migrants in 17 countries throughout the region, as well as vulnerable Venezuelans inside Venezuela since Fiscal Year 2017, according to the U.S. Department of State. This includes more than $1 billion in humanitarian assistance to Venezuelans inside and outside the country since 2017, the largest contribution of humanitarian assistance by any single country donor.

"The State Department will continue to build on our longstanding efforts to promote human rights by being responsive to the President's call in the February 4 memorandum to advance the human rights of LGBTQI+ persons around the world," explains acting principal deputy assistant secretary, Scott Busby, who covers LGBTQ+ issues in the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor at the U.S. Department of State.

He continues, "The Department will lead U.S. government implementation of the guidance detailed in the Presidential Memorandum and will work in coordination with relevant federal agencies to ensure that our diplomacy and foreign assistance advances nondiscrimination; combats criminalization of individuals on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, and sex characteristics; ensures swift U.S. responses to human rights violations and abuses of LGBTQ+ persons; and protects vulnerable LGBTQ+ refugees and asylum seekers."

In nearly every refugee crisis across the world, LGBTQ+ people suffer abuse, sexual harassment, and even rape and murder in their new host countries. Unfortunately, many of these cases go unreported for fear of retaliation, which includes deportation.

Furthermore, when refugees choose to claim asylum on the basis of their LGBTQ+ identity, they are met with barriers that require delicate approaches from the asylum seeker, humanitarian workers, and immigration officers. For example, to claim asylum based on sexuality or gender identity requires that evidence be provided to support the claim. This includes the provision of witness statements corroborating their claim. That task is difficult and can endanger asylum seekers and their families, especially if they are detained much like many are in the United States.

Victor Madrigal-Borloz, a gay Costa Rican lawyer, senior visiting researcher at Harvard Law School, and the United Nation's Independent Expert on Protection Against Violence and Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity, has spent most of his adult life investigating the nuances of LGBTQ+ discrimination across the globe.

"The situation of LGBT refugees and asylum seekers is of great complexity," says Madrigal-Borloz. Take the LGBTQ+ acronym, for example, which he says is "more political" and Westernized. Even though many cultures across the world might not relate to the acronym, Madrigal-Borloz explains that people are suffering "enormous violence and discrimination" due to it being weaponized. This of course complicates things further when you're dealing with matters of identity, acceptance, and policies.

Madrigal-Borloz, who began his career at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, was appointed to his latest role in January of 2018 to examine, monitor, advise, and publicly report on matters related to such human rights violations. He is only the second person to have had this role and has certainly not been shy of controversy by calling out hate speech of religious leaders and members of state.

In a July 2020 letter to the Turkish government, Madrigal-Borloz criticized Ali Erbas, the president of the directorate of religious affairs in Turkey, who blamed homosexuality and premarital sex for the spread of HIV and COVID-19 while encouraging people to "come and fight together to protect people from this kind of evil" on national TV. His comments spurred a hate campaign against the LGBTQ+ community and later gained the support of other political leaders in Turkey including President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

"It is so important that you contrast situations where you may have leaders that flatly deny the existence of LGBTQ+ persons living under the jurisdictions of their states, to those that actually not only acknowledge it, but give value to the way in which systems need to be responsive to it," Madrigal-Borloz explains. "I have seen families turn from fear to acceptance. It is through the hard work of civil society and the notion of responsibility of those that get elected politically, and choose to actually do the right thing, that good things have happened throughout my lifetime. So it is literally impossible for me not to have hope."

With a lack of funded research and little training being provided across all agencies and nongovernmental organizations, some of the world's most vulnerable populations are being failed by the systems that are meant to protect them.

"The United States stands up for and defends the human rights of LGBTQI+ persons, in Venezuela and around the world," explains Ned Price, the U.S. State Department Spokesperson. "The United States works with international and non-governmental organization partners to ensure and provide equal protection and support to at-risk populations who are particularly vulnerable due to their sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, and/or sex characteristics and those who seek to provide critical assistance to the community. We demanded and worked for the release of the five employees of Azul Positivo in January. The United States firmly opposes the targeting of and abuses against LGBTQI+ persons."

While worldwide organizations are rising to meet these challenges despite such roadblocks, which include gaps in funding for research and sensitivity training, there are still many LGBTQ+ organizations that fail to see this as a human rights issue but rather an immigration issue.

Still, despite it all, queer Venezuelans like Arellano continue to use their story in an effort to reclaim a country that was stolen from them.

"So what is next for you?" I ask Arellano, who is nearly recovered and seeking asylum in Brazil. What he says surprises me.

"The world is in pain," he answers. "We are in pain. All I can do, all we can do, is to love each other."

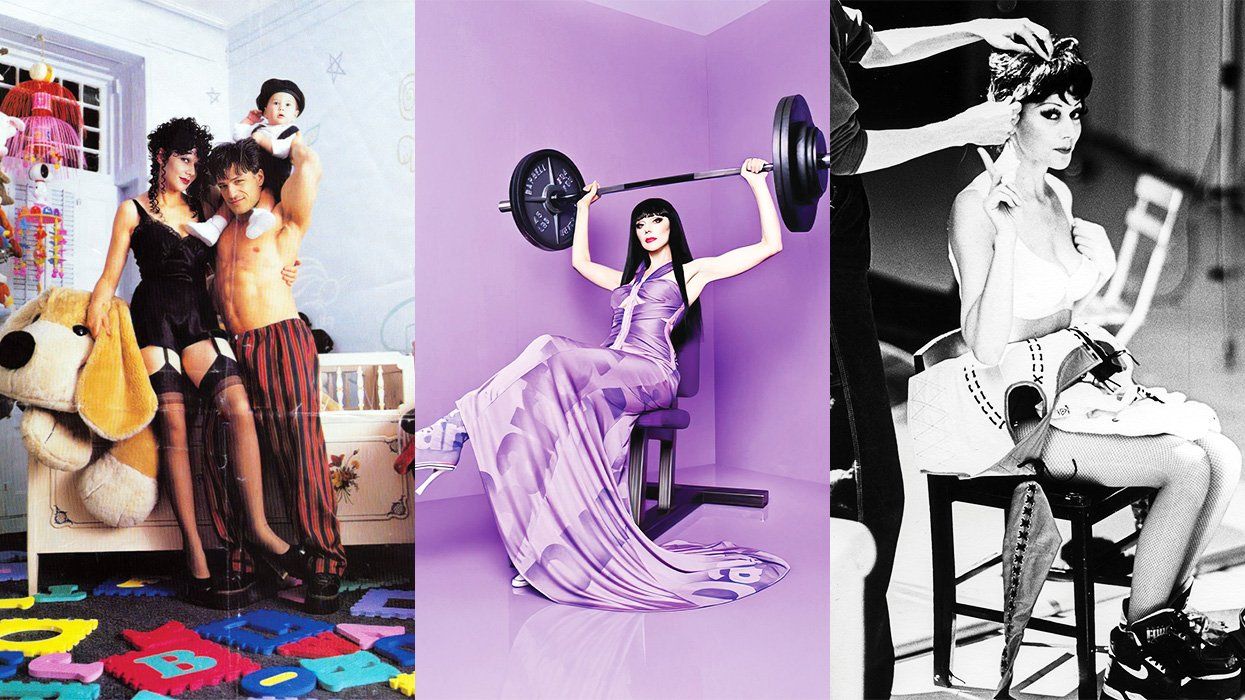

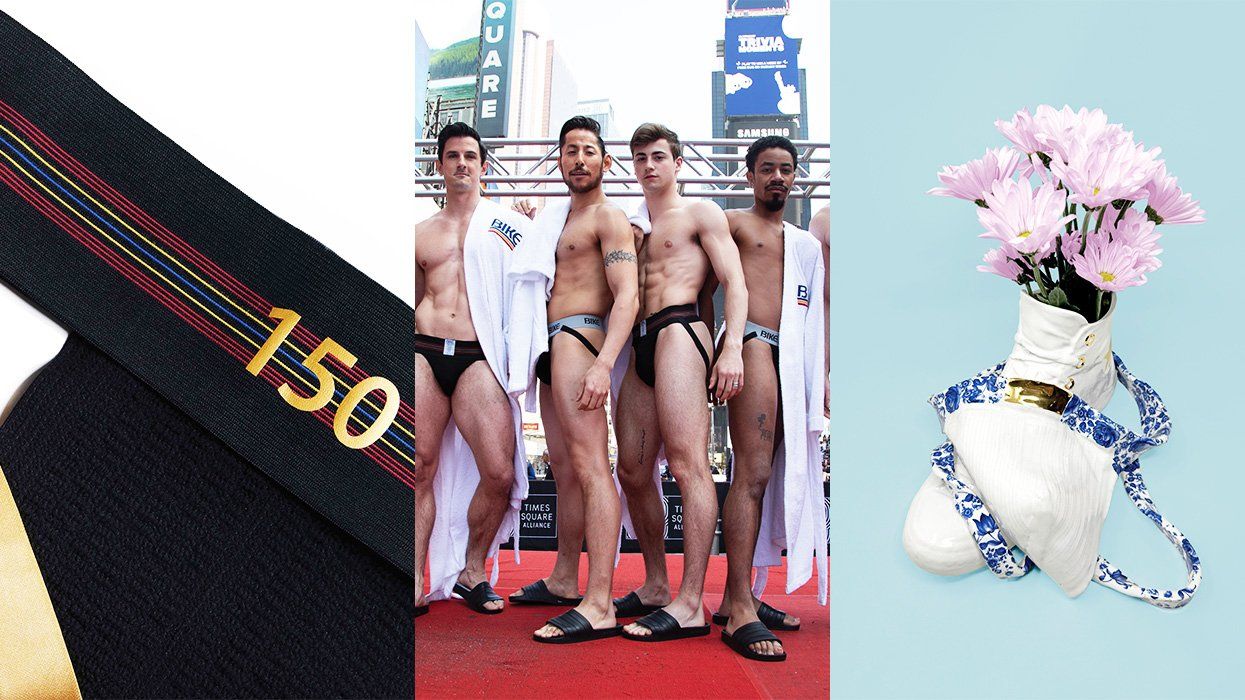

Photography by Cody Mann.

Additional reporting by David Artavia.

Translations by Camilla Olivia and Arjenis Mena.

Style assist: Claudia Torres Rondon (New York City).

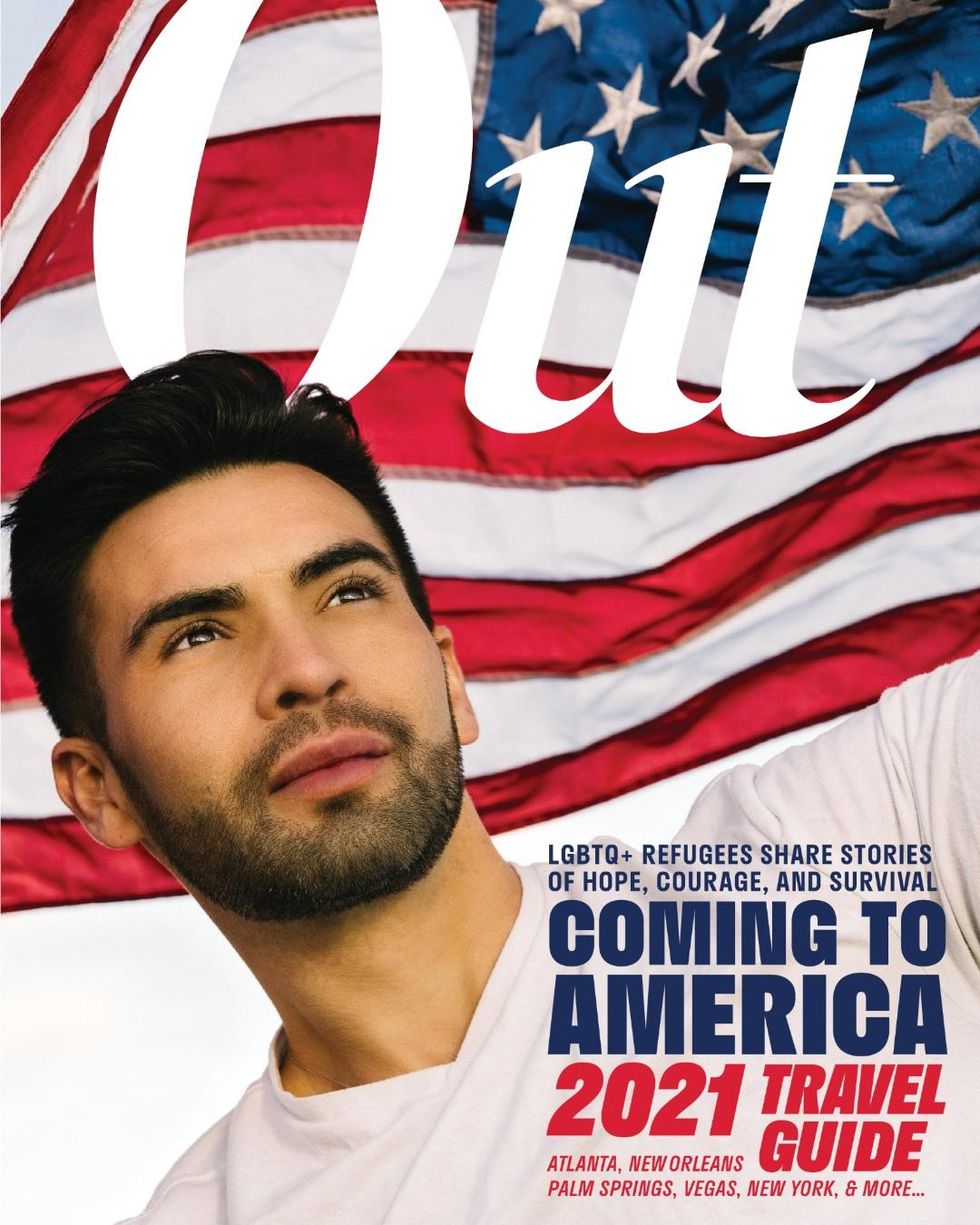

This cover story is part of an investigative series for Out's 2021 Travel Issue, the first in the magazine's history centering on Latin America. The issue is out on newsstands on April 28, 2021. To get your own copy directly, support queer media and subscribe -- or download yours for Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.