A magical fairyland with equal amounts glitter, hustle, and human excrement, early '90s New York was the ideal nexus of time and place to birth Out. Officially launched in the summer of 1992, the magazine by and for queers sprung from the minds of established Gotham journalists like founder (and editor in chief) Michael Goff and Sarah Pettit, the first editorial hire.

"Half the first issue was produced at the Esquire offices," Goff, a former editor of that iconic -- and at that point, very straight -- publication, recalls.

Even though Goff was initially wedded to naming his new publication Rogue, it became clear the magazine had to be a bold declaration of queerness. "If we're going to do this, we have to do it as a definitive act," says Goff, who had to ask Interview editor Ingrid Sischy to use the name, since her publication already had a party column called "Out."

When it came to being here and queer, Goff certainly led by example -- he was an active member of ACT UP and occasionally jailed for his activism. But Goff had an eye for commerce too, and managed to find the embryonic niche publication investors, who "asked a 26-year-old to find an audience and contributors and advertisers when there were none. The key things were not there and frankly, if I wasn't 26, I wouldn't have done it."

With design guru Roger Black establishing the magazine's visual style and some start-up money in hand, Goff could focus on the fun part: hiring LGBTQ+ journalists and producing content for an audience hungry for substantial stories and glossy escapism after years of the Moral Majority, Reagan, Bush, and a plague. While the closet was an impediment to coverage ("you had [Pedro] Almodovar and Harvey Fierstein and you were done," Goff says of out celebrities at the time), it was not for staffing. The publishing world was flush with queers, many of whom felt extremely stifled in their work lives.

"I knew a lot of people who were gay and lesbian in mainstream publishing and who weren't able to do the stuff they wanted to do where they were. It was unlike today, when [mainstream publications] fall over themselves for gay stories," Goff says. "There were all these people realizing they were in New York and not out and wanting to be out. All these people who had been basically closeted at work in mainstream media were able to do their part for gay rights."

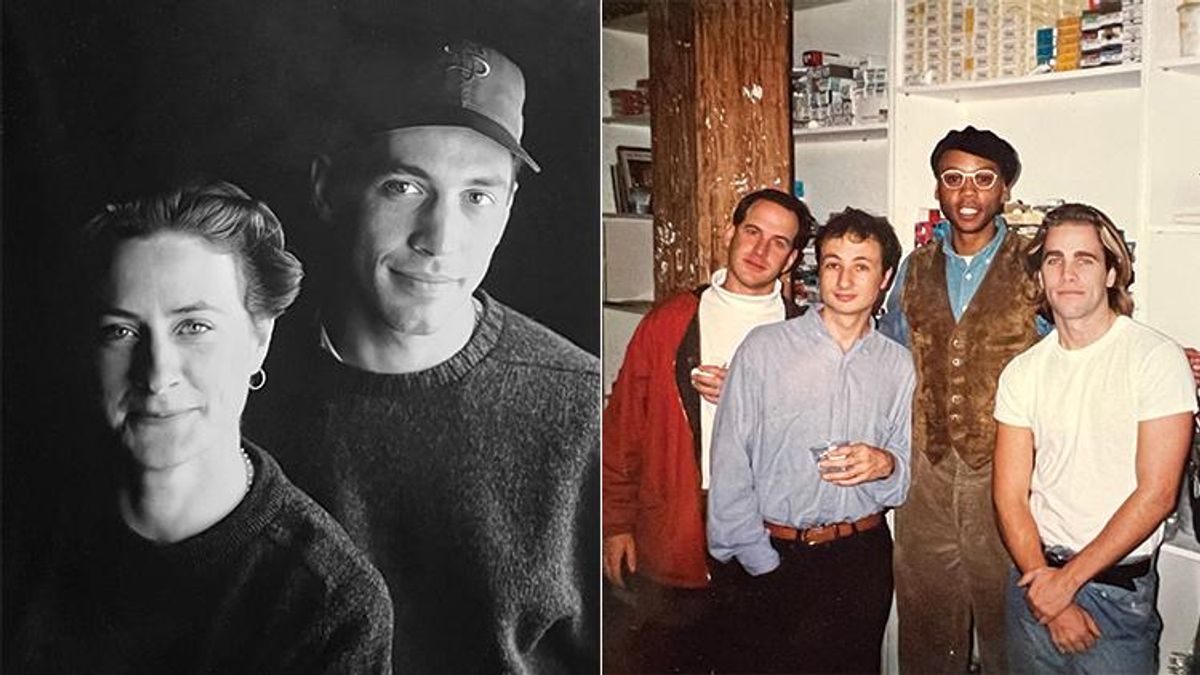

Pictured: Advertising director Mary Connelly, editors Vincent Boucher, Frank DeCaro, Michelangelo Signorile, staff writer Michael Musto, writer Jim Colucci

Pictured: Advertising director Mary Connelly, editors Vincent Boucher, Frank DeCaro, Michelangelo Signorile, staff writer Michael Musto, writer Jim Colucci

Goff's most important hire was executive editor Sarah Pettit, a lesbian Yale graduate who previously helped edit the queer alternative newspaper OutWeek, which went belly up in 1991. Pettit and Goff ran in the same East Village circles and were both involved in ACT UP. With a gay man and a lesbian partnering to create content, Out developed an identity that was more inclusive for queer publications at that time, including its main competitor, The Advocate (Out and The Advocate now have the same owner). Queer women and men worked alongside each other and generally respected each other's ideas, Goff says. "If Sarah came in and told us we had to do something -- say, about opera queens -- we'd be like, OK whatever, sure."

Though the magazine would not have a high-level editor of color for years, Goff is proud that acclaimed writers of color like Alexander Chee and Linda Villarosa and creatives like art director Anneliese Estrada cut their teeth at Out during its earliest days. Goff also sings the praises of editor Bruce Steele, who would later run The Advocate, and staff writer Anne-christine d'Adesky, revered for her HIV reporting. The staff considered themselves progressives and took their activism seriously, with most of the team attending 1993's epic March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation.

"We all got a train ride to the march, which was kind of over the top and hilarious," Goff says. "Frank DeCaro actually wrote a very fun piece about it and described me as a camp counselor, along with Sarah.... We had really good parties."

Even though most of the staff was "well under 40" they all had a sense of purpose, Goff says, and were committed to doing important work. "The thing that set us apart was we did big stories, longer stories, 10,000-word stories. We sent Mike Signorile to Hawaii where they were trying to start marriage there, which we thought was hilarious." There were features on "don't ask, don't tell," the origin of AIDS, lesbian punk rockers, and the emergence of the internet. "With a lot of the stories, we beat The New York Times by a couple of months," Goff says.

Even with its reputation growing and Madison Avenue (eventually) calling, the magazine's finances were highly precarious during the early years. Goff would depart in 1996, leaving Pettit as sole editor in chief. By that time, she had become a "fashion plate," Goff says, regularly attending the fall shows. But new executives wanted to move Out from its more egalitarian beginning and rebrand it as almost exclusively for gay men. Pettit was pushed out in 1998.

"They fired her because she was a woman," Goff says of Pettit, who ended up suing for discrimination. "She didn't get the support of a lot of lesbians in New York, which I know was very hurtful too."

Pictured: Publisher Harry A. Taylor (left) and guest at an Out party

Pictured: Publisher Harry A. Taylor (left) and guest at an Out party

Pettit quickly moved to another high-profile job as arts and entertainment editor of Newsweek. By all accounts, Pettit blossomed in that position -- until she fell ill in 2002. Pettit's lymphoma was aggressive; she died the following year at the age of 36. NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists has named an award for her, which it bestows annually to an out journalist.

Meanwhile, Goff segued to the internet after Out, working at Microsoft and currently serving as the owner of LGBTQ+ blog Towleroad. His time creating Out was a special moment, he says, where the community was riding on a wave of optimism from the Clinton administration and newly approved AIDS meds.

"Being a magazine editor at the beginning of the '90s was the best job you could ever have," he says. It wasn't just about the town cars and expense accounts, though. It was fun, Goff says, but working in journalism back then meant you could cover whatever you wanted and use that experience to glide into other fields, which were opening their doors to out employees. "You want to do fashion? Sure. You want to do politics? Sure."

Of his time at Out, Goff may be most proud of the talent fostered at the magazine, describing numerous staff members who clawed their way to the top of mastheads, wrote best sellers, nabbed awards, or became regular presences on television.

When he started the magazine, "other people thought we weren't going to make it through a year." It was the publication's authentic voice and commitment to the community that saw it through, he says. "It's hugely beneficial to be part of a movement."

Lead art: Black-and-white photo of Goff and Pettit by Todd Eberle producers; Randy Barbato (left) and Fenton Bailey, RuPaul, and designer Matt Nye celebrate Out; L.A. party images by unnamed photographer; all other images courtesy Goff

This article is part of Out's July/August 2022 issue, now on newsstands. Support queer media and subscribe -- or download the issue through Amazon, Kindle, Nook, or Apple News.

RELATED | Why Neil Patrick Harris Isn't Afraid of Aging or Dropping His Pants

Pictured: Advertising director Mary Connelly, editors Vincent Boucher, Frank DeCaro, Michelangelo Signorile, staff writer Michael Musto, writer Jim Colucci

Pictured: Advertising director Mary Connelly, editors Vincent Boucher, Frank DeCaro, Michelangelo Signorile, staff writer Michael Musto, writer Jim Colucci Pictured: Publisher Harry A. Taylor (left) and guest at an Out party

Pictured: Publisher Harry A. Taylor (left) and guest at an Out party