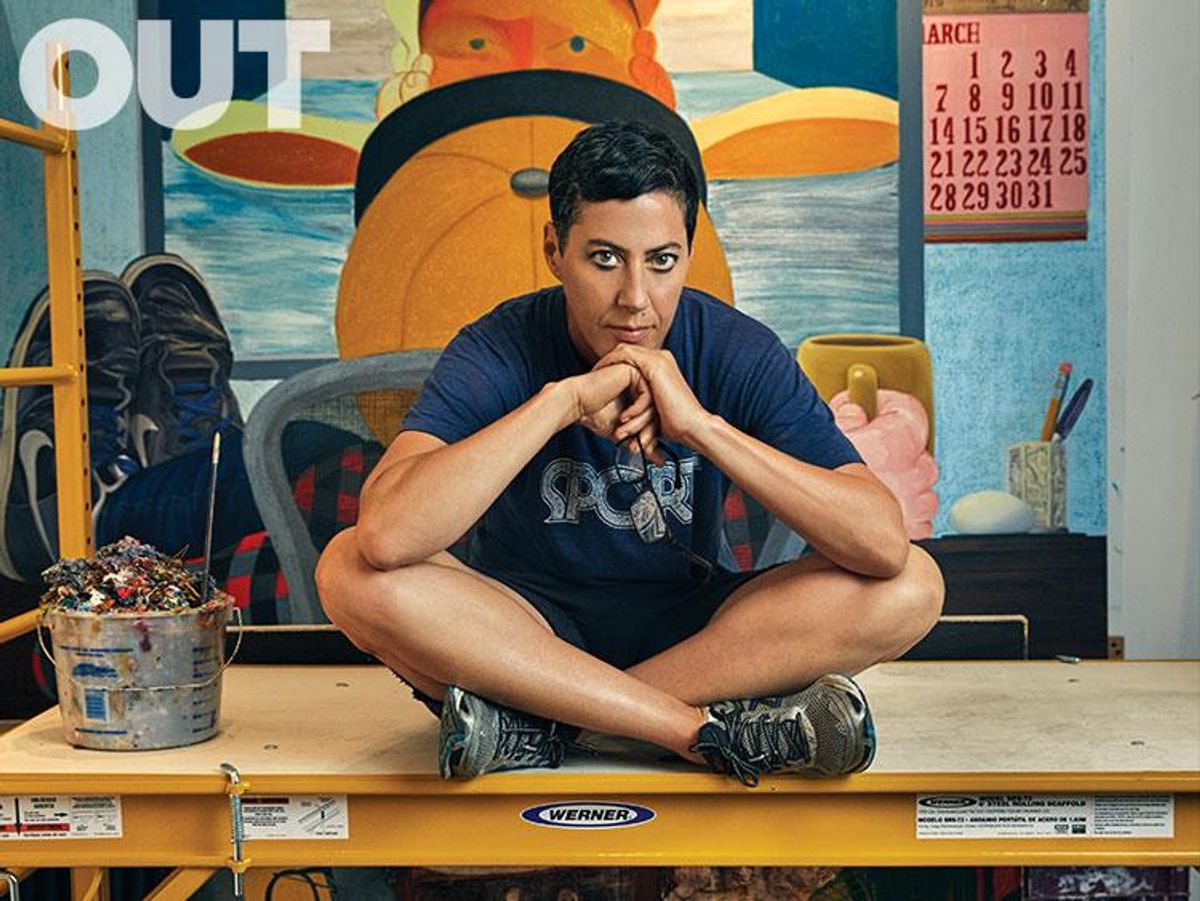

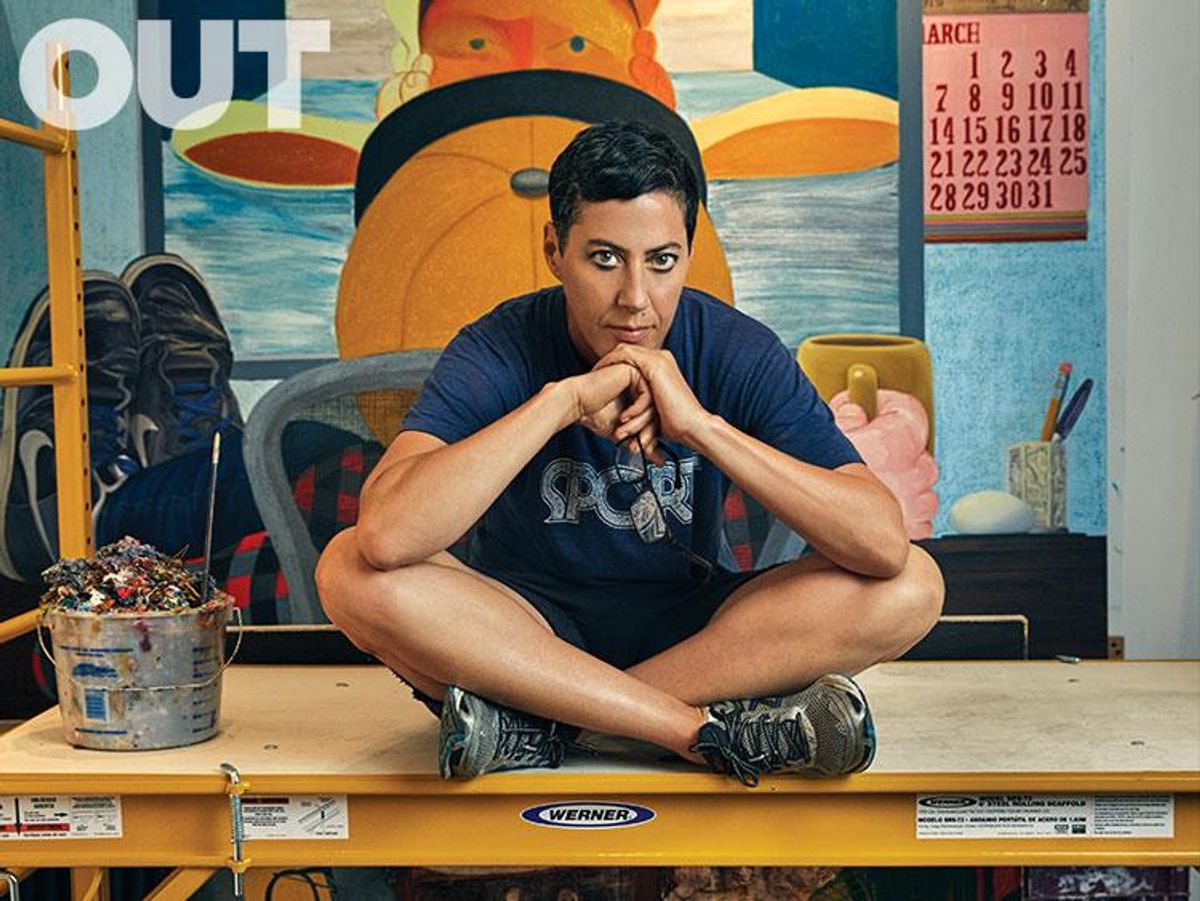

Running into the cold, restorative waves with artist Nicole Eisenman

September 16 2015 5:00 AM EST

September 16 2015 10:06 AM EST

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

Running into the cold, restorative waves with artist Nicole Eisenman

Photography by Sophy Holland. Groomer: Angela Di Carlo.

My first time visiting Fire Island -- Labor Day weekend, August 2014 -- I got lost. I'd been at a party for a resident artist and couldn't find my way back to the house I was staying in. Everything looked the same in the dark. After an hour circling the Pines, I gave up and crashed in a construction site near the ocean. A few hours later, I awoke with the sun, only to find the house just 20 feet away. The painter Nicole Eisenman, who spends much of her summer there, was having breakfast alone on the porch. "Oh, you look like shit!" she said, smiling. "Come on, let's go for a swim." We headed to the beach, stripped, and jumped into the cold water; the waves were huge, rolling, and speckled with harmless jellyfish. Eisenman never asked me to explain, and didn't need to. I felt cured.

Eisenman has spent the last three summers in the Pines at a house she shares with many other artists, curators, and writers, an informal and not so clearly defined circle of friends (most of them from New York City). They call their tiny community the Tamplex, a name bequeathed by artist K8 Hardy, who acts as a housemother through the summer, alongside her partner, curator Pati Hertling. The house has changed a few times, but the residents and their steady rotation of guests have remained largely the same. A lot of people come through, fit in, make breakfast, stare at the water, and debate whether or not to go to the underwear party. "The play of the public and the private is so interesting there," Eisenman told me over lunch recently in Brooklyn, where she lives and works. "It's down to the wood. I was talking with Sam Ashby about this" -- Ashby is the editor of Little Joe, a London-based queer film magazine -- "and he mentioned that the dock you land on is made of the same wood as everyone's homes. The boardwalks turn into these private walkways that end at homes where the doors are usually unlocked and the windows are open. The public and the private become these overlapping spheres, and everyone lives in the middle."

It's a social complexity reflected in her work, which also sits at the points where those spheres intersect. In her paintings, figures often seem as though they have struck a private pose in public, making a face they might make in a mirror except that they are making it for an audience, for "the viewer." Eisenman is perhaps best known for her portraiture, where multi-colored faces appear in the between-states of the various cycles of feisty emotions -- some of them big, some small, some devastated, some mournful, some grinning (stupidly), some neutral and contemplative. They are common expressions often made uncommon, squared in paint to curious effect. A woman sits with death. A woman performs oral sex on her lover, their bodies resting beside a stack of books and an Eve Fowler print ("It is so, / is it so, / is it so, / is it so / is it so / is it so," it reads, a quote from Gertrude Stein). Eisenman's work is big, gay, and funny, borrowing a humor that is often deeply New York, deeply lesbian, but also deeply none of this, or only ambivalently so. In her essay on Eisenman, the poet Eileen Myles writes: "Nicole has always had the gift of unselfconsciously converting her own self-consciousness into yours."

More often, she is conscious of the daily, shifting psychologies of our relationships to history, both the personal and the social. In her 2009 painting The Triumph of Poverty, the ragtag poor pose next to a beaten-up car, facing left with a resignation that almost feels determined, not so much defeated as savvy to the economic system that put them together and down. A pea-green child stands next to a man with his pants and underwear pulled down to reveal his butt is in front and not in back, and holds a cup up to no one. She stands over a tiny band of people struggling to stay up, their leader tied to a thread held by the man with his ass out. The people seem to belong to the Depression era, but, then, it's our era, too, coming on the heels of the Great Recession to remind us that things change, but often they stay the same.

What does Eisenman think about when she's on Fire Island? "Ghosts," she says, explaining that the island evokes -- or rather is haunted by -- the spirits of a generation of men and women: artists, thinkers, people of color, the affluent, the middle class, the ignored, the displaced, those let down by their government, those who caught the disease too early, those who didn't realize they had caught it at all, those who thought they would never catch it but who did, all of those who were lost to the dark times when she first came to New York City in the early 1990s, at the height of the AIDS crisis. Many gay men and women, many of whom would have been her peers, were dead and many more would die later. Her first major institutional show, a group exhibition of wall drawings at the Drawing Center in 1992, occurred the year activist Mary Fisher rebuked the Republicans for their policies of silence, tennis star Arthur Ashe had announced that he had been living with HIV for years, and the FDA approved the use of ddC in combination with AZT. It was a time of further disappearances. Crisis provokes lists: We count what's gone and what remains. Everywhere the island attests to the dead, to the bodies who are not there, the figures who might have been paintings, the figures who might have loved paintings. "You can feel them there," Eisenman says.

It's a sweltering mid-July afternoon in Crown Heights and an almost overwhelming mugginess has enveloped the whole of Brooklyn. We're both aware of how far we are from the breezy relief of the Long Island coast, where nearly a year ago we swam naked for my hangover cure. Eisenman tells me she has been recently spending her days on the island drawing her friends. Later that night, she sends me images of the small works on paper. A woman sits looking at her computer, her head held up by her left hand. A man lies naked on a towel strumming a guitar while a woman, her legs open to reveal tufts of pubic hair, listens intently. Friends lounge on the beach, make a human pyramid, and check cell phones against a backdrop of beach grass. I consider the living as she considers them. Drawing is a way of keeping them there.

Beware of the Straightors: 'The Traitors' bros vs. the women and gays