Think Memphis, think barbeque and blues. Think also of the King, who found his swiveling hips there, along the banks of the Mississippi River. The city may be home to blue suede shoes, but since 1986, it has also been home to pink satin pointe shoes. More than 25 years ago, Dorothy Gunther Pugh, a fifth generation Memphian and Vanderbilt graduate (in other words: Tennessee in the flesh) founded Ballet Memphis, which arrives at New York's Joyce Theater this week for the first time since its debut in 2007.

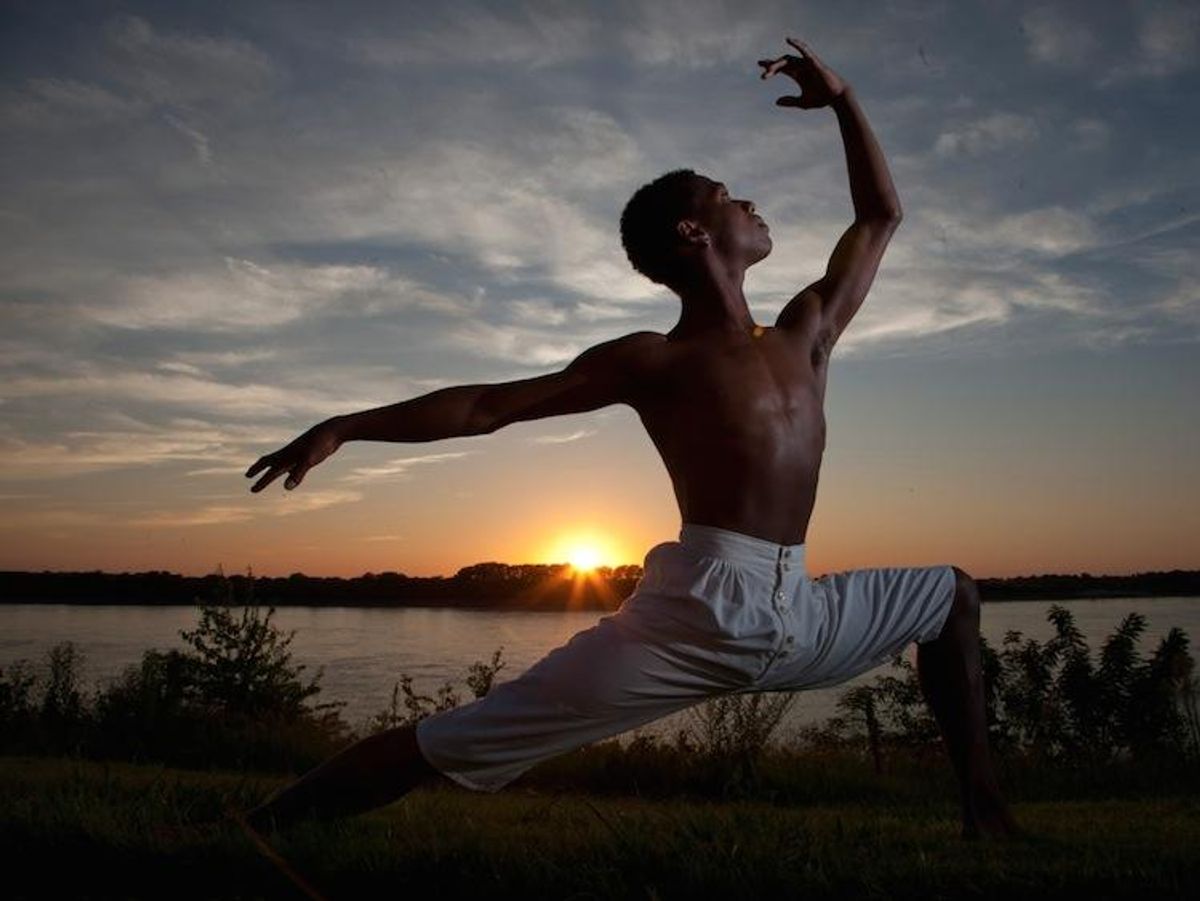

"The company was young and still trying to figure out our voice in the dance world," dancer Kendall Britt says of that visit, which was during his first season as a company member. (He was young, too: He turned 20 on the tour; at 28, he now calls himself part of the "old generation.") Audiences this time around can expect a more mature troupe, he says.

"We're more experienced," says Britt. "We've done more touring in the past 10 years. And we're also more humble."

A mid-size, Midwest ballet company would be forgiven for feeling a tad intimidated performing in the international dance mecca of New York. But Britt, a native New Yorker who studied at the La Guardia High School of the Performing Arts and used to skip school to see shows at the Joyce, dismisses that idea. "We're not trying to prove something," he says. "We're at a place where we fit in, but there's a different perspective. We have something to say there."

What Ballet Memphis has to say is a statement on homegrown creativity outside of major metropolises, and a commitment to honoring and cultivating one's local roots. Kind of like farm-to-table, for the arts. "The work we do is primarily about the city and the culture of the city," says Travis Bradley, a company dancer for 12 years.

In the past decade, Pugh has launched several major initiatives to make Memphis a muse for commissioned choreographers, including The Memphis Project and The River Project. (Works from those projects comprise much of the company's two programs this week.) That may mean using the music of local legends like B.B. King, Aretha Franklin and Elvis Presley, or drawing from the city's literary roots. "We look for stories that represent the people that have been there," says Britt. As Bradley put it: "It makes you feel a part of something."

Examples on stage this week include The Darting Eyes, choreographed by Matthew Neenan, which meditates on the tradition of baptisms in the Mississippi River, and Devil's Fruit, by Julia Adam, inspired by the rich fungi ecosystem along the river banks. More broadly, Confluence, by Steven McMahon considers the concept of community, which resonates with many of the dancers who have made Memphis home, often to their surprise.

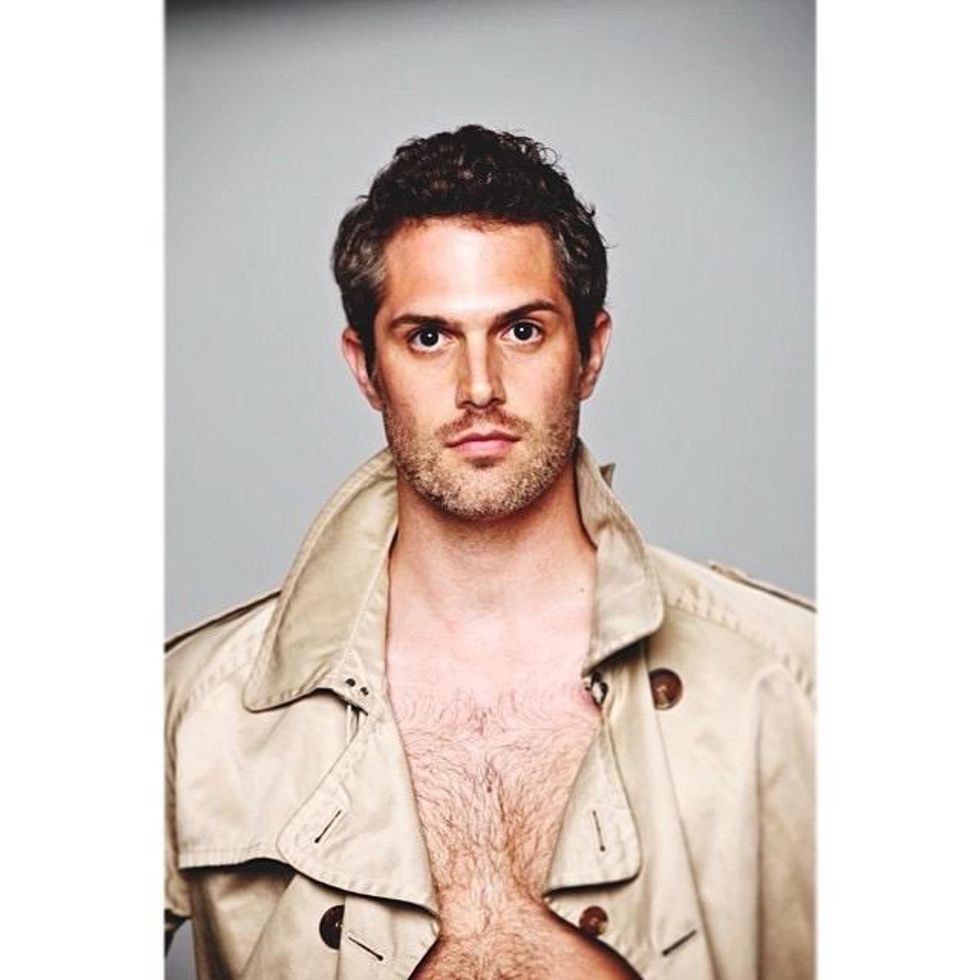

Travis Bradley

"I grew to love Memphis," says Bradley, a Southern boy who was raised in Virginia and did a stint with the Houston Ballet but found that city too big. "I love the grit, I love the honesty. It's not pretentious, just real and aware of what it wants to be." Bradley and his partner, Jordan, "a theater guy," recently bought a house in the Midtown neighborhood, which has grown in recent years into a cultural district, sprouting trendy restaurants and shops.

In June, Ballet Memphis announced that it, too, plans to move its headquarters from the suburbs and join the artistic boon in the city.

"There's kind of an urban renaissance going on, and if you look, this is happening in cities around the world," Pugh told the Memphis Daily News this summer. "I've long felt - and it's why I live in Midtown - that there's something about pockets of creative energy that are really important to communities."

Pugh sees the move from the perspective of serving the community, which is how she sees every other aspect of the company's art and operations. Outreach is a priority of the organization, which has been on the forefront of diversity efforts in dance for underserved populations and women in leadership (Pugh is one of very few women to establish and run an American ballet company).

"We're in a lot of diversity conversations at Ballet Memphis, and we've made an initiative to diversify," says Britt, who was the sole black dancer at the company when he arrived but is now one of several. "As a black male, you don't really see your image reflected in the arts."

That fact has never deterred him, but he acknowledges that being in a smaller company like Ballet Memphis has afforded him opportunities he may not have had otherwise. "I've been Prince Charming and Romeo and Puck," he says, referring to iconic ballet roles. "To be a classical lead or a romantic lead was never the path set for me."

The case may be true for many of the hundreds of dancers across the country whose careers take them to similarly modest, so-called "regional" ballet companies, which basically means any company outside New York, Chicago or San Francisco or that doesn't have a budget in the tens of millions of dollars (Ballet Memphis' budget is $4.4 million; New York City Ballet's is 12 times that).

Referring to them as regional companies may sound patronizing and New York-centric (which New Yorkers, and New York dancers, certainly are) but these companies make up a vibrant and important biome of the American dance ecology.

A 2014 report by Dance/USA, a national advocacy organization, lists over 350 dance companies nationwide with budgets over $100,000, about half of which have the word "ballet" in their name. And many hail from cities and states that a New Yorker might write off as cultureless: Ballet San Jose, Ballet Wichita, Ballet Tucson, Ballet Pensacola, Ballet Nebraska, among others.

Earlier this year, Dance Spirit Magazineexplored the professional advantages of joining one of these troupes, which include healthier working environments, new artistic perspectives and unique opportunities to grow. All of which is why Britt has stuck around in the South for so long.

"Being in Memphis is a gift because everyone can be a big fish in a medium pond," he says. And when you're a big fish, your splash matters. "I think my dancing is more valuable here because it's needed here."

Ballet Memphis performs through Nov. 1 at the Joyce Theatre in New York City.

Sexy MAGA: Viral post saying Republicans 'have two daddies now' gets a rise from the right