From America's Next Top Model's Nyle DiMarco to the Broadway stage, deaf culture is being seen, it's being heard, and it's being celebrated. Those who feel that it's too soon for a Broadway revival of Spring Awakening--the 21st-century musical adaptation of a 19th-century play about adolescence and sexual discovery that originally made stars of Lea Michele and Jonathan Groff--which closed in 2009, have clearly not yet ventured out to the Brooks Atkinson Theatre to see the current Deaf West production.

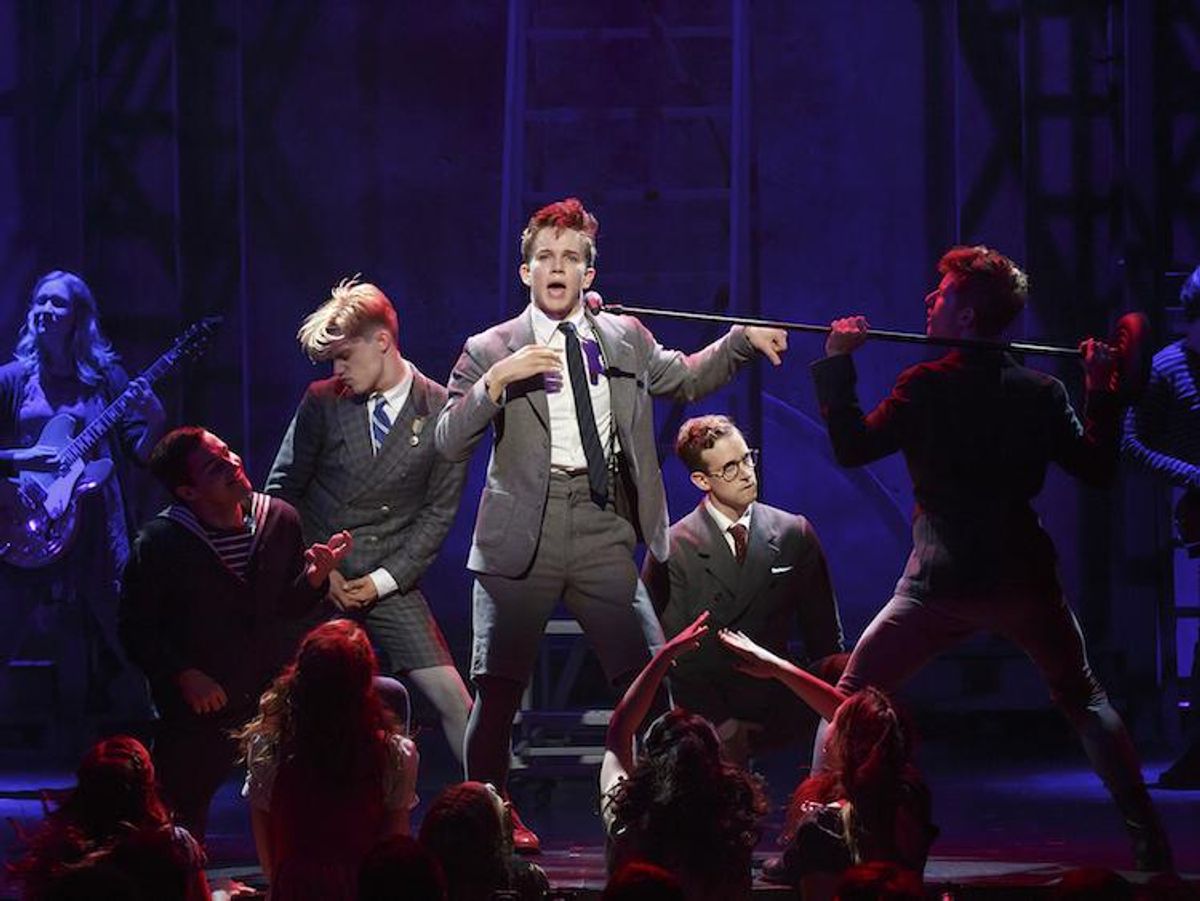

Directed by Michael Arden, the choreography by Spencer Liff incorporates the American Sign Language (ASL) translation of the lyrics and dialogue, the product of a team of ASL masters, giving meaning to even the smallest of gestures. The effect is mesmerising--more than simply doing justice to the power of the original, it adds a new layer of meaning, enriching the experience for audience and cast members alike.

RELATED | Spencer Liff: The Master of Hands and Heels

Set in a small German town in the 1890s, the show centers around the community's youth, a collection of 14 to 15 year olds living under the strict regimens of their parents and teachers. As Melchior Gabor, a rebellious and open-minded thinker (played exquisitely by Austin P. McKenzie in his theatrical debut), muses in the song "All That's Known," "thought is suspect" to the adults in their lives, who expect the young people to simply follow their teachings without question, whether it's translations of Virgil's Aeneid or the idea that a stork brings women their babies.

The show opens with Wendla Bergman (acted by Sandra Mae Frank and voiced by Katie Boeck), asking her mom to explain where children come from. Her mother, played by Golden Globe-winner Camryn Manheim (who also lends voice to the parts played by Academy Award-winner Marlee Matlin), agrees to tell her after Wendla threatens to ask their chimney sweep, only to back out of the anatomical details at the last moment. "Mama who gave me no way to handle things"--lyrics from the show's opening number--serve as a sombre allusion to Wendla's fate: becoming pregnant through an act about which she was never taught, never told to avoid, due to her mother's embarrassment at broaching a sexual taboo.

Comprised of both hearing and deaf actors, the show is fully accessible to both audiences, with every role being spoken and sung as well as signed. Scenes that are done purely through speech or fully through sign, artistic choices that add weight to the events being shown, are accompanied by projections of the dialogue. Many characters are actually split between a hearing and deaf actor, with the deaf actor playing the dominant role but displaying touching moments of intimacy and connection with their hearing counterparts, their voices. The ways in which the actors interact actually give insight into the characters themselves. For example, Joshua Castille and Daniel David Stewart, who play the content and untroubled Ernst, are very affectionate, holding hands and exchanging kisses on cheeks. Treshelle Edmond and Kathryn Gallagher, on the other hand, who split the part of the abused Martha, spend the entire show on opposite ends of the stage, coming together only to mourn the death of a friend.

Similarly, the use of sign language adds another layer of meaning, offering a complementary or, in some cases, supplementary visual message. Just as Wendla's mother is about to explain that a woman must love a man with her "vagina," she quickly moves the sign up to her heart, transforming the message to "she must love her with her whole heart." When Marianna Wheelan, played by Ali Stroker for the song "The Bitch of Living," is introduced, she rolls across stage in her wheelchair with the flick of her hair, the first person to perform on Broadway with such a disability. Later, when Hanschen (played by Andy Mientus) sets out to seduce Ernst, his seemingly innocent observation of the sound of bells tolling in the distance becomes laden in sexual innuendo as his closed fist rhythmically slams into his open palm.

While there shouldn't have to be any larger reason for a show to translated into ASL--or at least, nothing more significant than the fact that the the deaf community, like the hearing community, could find enjoyment in it--the parallels between the experiences of the young people in Spring Awakening and that of Deaf people today lend poignancy to Deaf West's production. "The children in this show are underprivileged," Joshua Castille tells Out. "They're oppressed, they're trying to make the best of a world that keeping saying no--and that's deafness! I feel like so many groups can connect with the idea of not being understood. That's why it works."

For avid fans of the show (I myself have seen it a total of 10 times over the years: five separate productions in two countries), this revival adds such a richness that, while familiar, it's an entirely new experience. For first-timers, it'd probably be hard to imagine a production without ASL, so seamless and fulfilling is its present incarnation.

Spring Awakening will finish its very limited run at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre on January 24. For tickets, visit the website.