For 25 years, OUT has celebrated queer culture. To mark our silver jubilee, we look back at some of the biggest, brightest moments of the past 9,131 days.

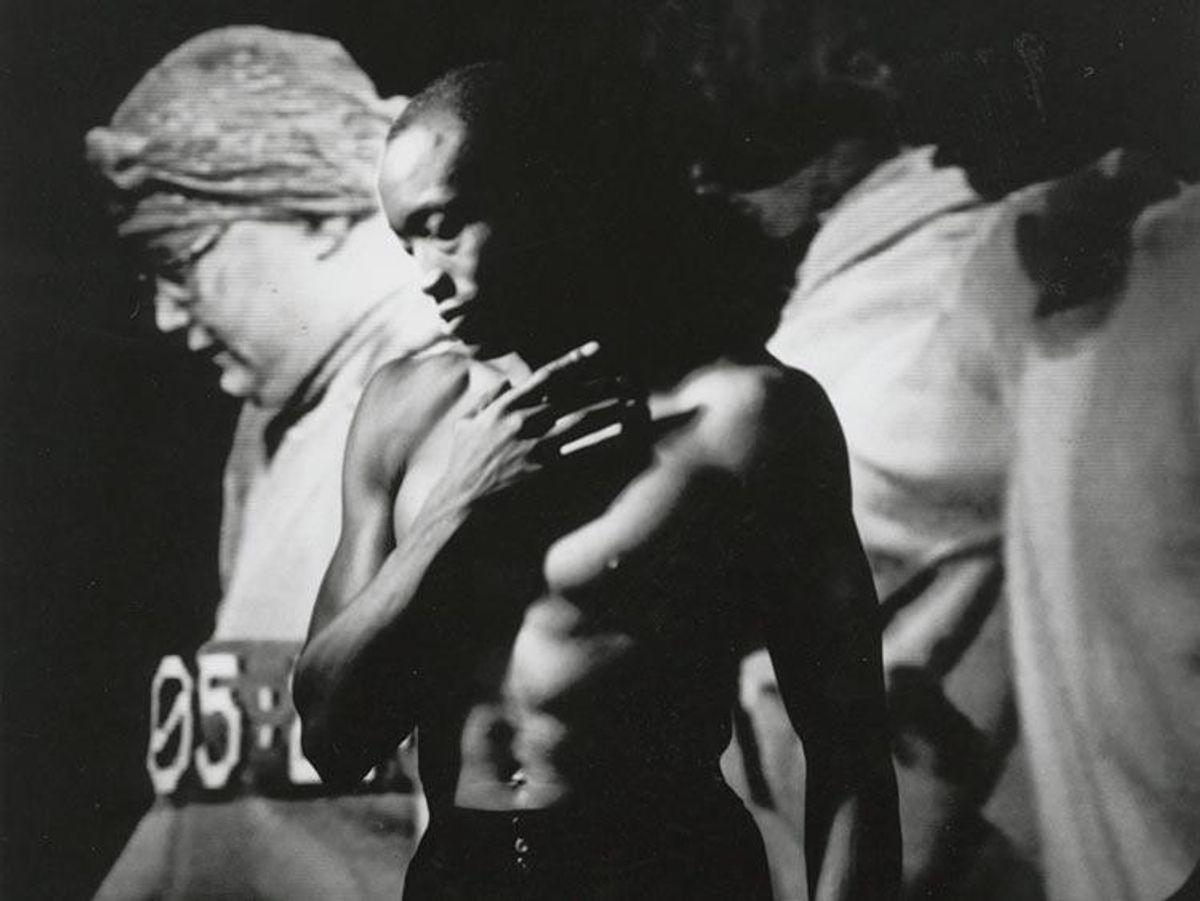

In the early 1980s,Bill T. Jones emerged as an exciting young choreographer who deftly bridged modern and post-modernist dance by mixing elegant physicality with unfussy aesthetics and pedestrian movement. As he was a black man dancing with his white, Jewish partner Arnie Zane, politics of race and sexuality were an appealing part of the package, too. By 1988, Zane had died of AIDS and Jones had been diagnosed with HIV. Fair or not, the disease became part of their legacy.

Jones didn't shy away from it. Identity--the labels we put on or that are put on us--has been, and continues to be, a primary preoccupation of his work. Terminal illness, he decided, was a label worth exploring, too. Over the course of a year, he convened Survival Workshops across the country, working with nearly 100 non-dancers of all ages facing cancer, AIDS, and cystic fibrosis, among other illnesses.

The resulting multimedia dance-theater work, Still/Here, premiered in 1994 and was hailed by critics as Jones's most important work, "a landmark of 20th-century dance." Well, most critics. In a now-infamous article called "Discussing the Undiscussable," The New Yorker's Arlene Croce refused to see or review Still/Here. In a lament veering from the state of arts funding to the diminished role of the critic, Croce dismissed artists like "disenfranchised homosexuals," whom she accused of "[making] out of victimhood victim art."

Like any good controversy, the brouhaha catapulted Jones to national fame and spawned debate over the value and validity of his methods and message. Jones, for his part, does not consider Still/Here--or any of his work--to be about AIDS.

"As a person who has to deal with his own possible early death, I was looking for people who are dealing with the same thing," he explained in a documentary with Bill Moyers. "My job is to evoke the spirit of survival."

Significantly, though, by including people with HIV and AIDS in his portraits of persistence, Jones presented them simply as individuals facing their mortality rather than as members of a stigmatized group in a political battle. Still/Here didn't differentiate between the various afflictions or dwell on how they were acquired--it was only interested in how one kept living and loving.

In contrast to the urgent activism of the late '80s with ACT UP's public protests and large-scale memorials like the AIDS quilt, Still/Here treated the disease as part of the long history of human health and suffering. Croce may have felt like a victim for having to evaluate the messiness of life through the filter of art, but for the many viewers who were deeply moved by Still/Here, Jones's dance was a powerful, participatory act of healing.