"How do you march in today's parade?" I turn around to find a teenage boy standing nervously nearby, avoiding eye contact when I answer him, saying, "You just march. This event is open to everybody." He's alone and clearly confused--his sheepish demeanor telling me this is his first time at such an event. "That's all?" he asks, before walking away to reluctantly join the others.

It's late morning in Puerto Rico and we're gathering at Parque del Indio in San Juan for Sunday's big Pride Parade. The group's been slowly building since 10 AM, and while most marchers seem well-prepared--rainbow flags in-hand with glitter caked in every crevice--the boy was a reminder that not all come to Pride as seasoned, confident queers--and especially not in PR.

Related | Gallery: Puerto Rican Pride

"The problem is more sociological than anything else," says Wilfredo Torres, PR's Pride Parade organizer. "People come to San Juan to go to bars and hang out, but this is one of the few [LGBTQ] events we have during the day. The Parade is an open space. We have press and everyone can see you, so some think, 'Maybe my parents will see me on the news, tonight.' Coming here and marching is a big step for a lot of people."

Of PR's total 3.4 million population, Torres estimates the U.S. territory has a LGBTQ community of approximately 50-75,000 people. The Parade is packed with thousands of attendees, but it's still only a small fraction of their entire queer population. Last year's march followed Orlando's Pulse shooting--a tragedy that saw 23 Puerto Ricans die--and gathered 9,000 people in response. This summer, Torres is inevitably anticipating smaller numbers, but certainly more than he would've expected when he started working on Pride a decade ago.

Related | OUT100: The Survivors & Heroes Of Pulse

"This is one of the smallest Pride Parades if you compare it to cities like New York," Torres says, though he's watched it gradually grow each year as PR becomes more tolerant of its LGBTQ population. Today, we're marching down Ashford Avenue, San Juan's main road, which is lined with dozens of hotels, restaurants and apartment buildings. For several hours, the Pride Parade will shut down the entire avenue, stretching for miles and halting regular traffic. This public action, Torres suggests, is among the strongest ways to promote queer acceptance in PR.

"Ashford is one of the most concurring avenues we have," he says. "Most of the hotels are in this area, so everyone can see the Pride Parade. They can see the LGBTQ community with their allies. Parents and kids are marching together. Employees for companies, like T-Mobile, are marching with us, as well."

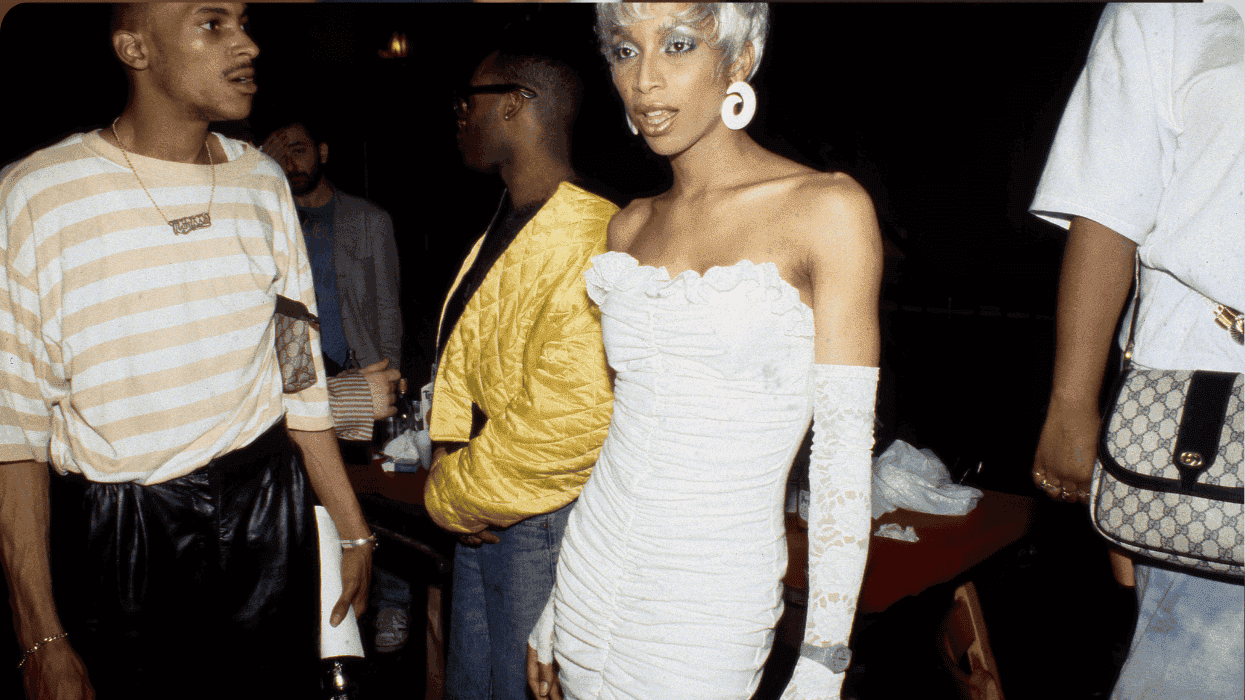

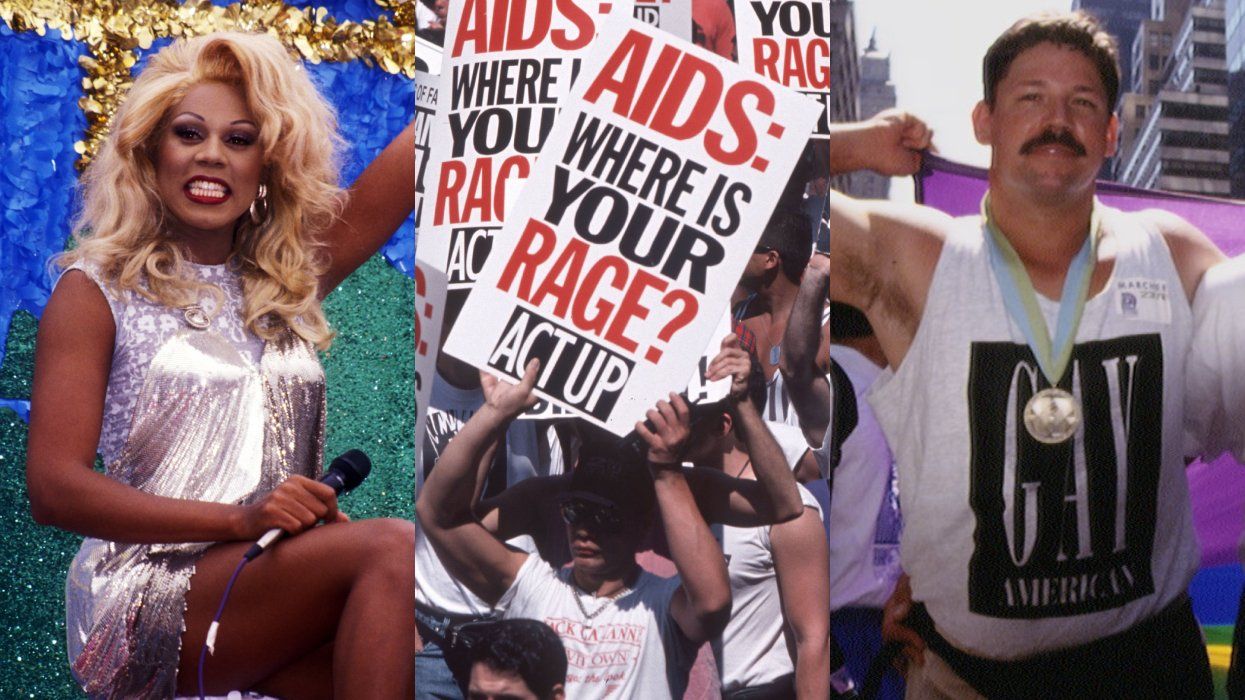

Unlike Pride in major metropolitans, PR's is largely grassroots with local clubs strapping colossal speakers onto the bed of trucks and filling the remaining space with resident drag queens who wave and hand out fliers with drink specials. T-Mobile is the Parade's only corporate sponsor, and the rest is filled with authentic queer marchers--not big businesses boasting flashy floats and an eye on the coveted pink dollar. This parade feels more genuine than most, like a true act of queer defiance and rare celebration--perhaps also because PR's homophobia is more public than in United States' larger cities.

"We have a few fundamentalists and conservative people in the state legislator working overtime to invent and pass new bills that allow discrimination against LGBTQ people," Torres says, specifically highlighting the Religious Freedom Act, which forces employers to accommodate religious practices, even if they're discriminatory. "They also have one to prohibit sexual and gender education in public schools. These bills may seem like small issues, but they have a big impact on our [queer] communities."

Among those targeted most heavily are transgender folks who have difficulties accessing health care and securing legal jobs, Torres says. On any given night, PR's street corners are densely dotted with transgender sex workers, so much so that it's become a cultural norm--integrated regularly into everyday society and accepted with far less stigma that in the States. "Our girls don't have job opportunities," Torres says. "They don't have education opportunities. So they're forced to do a few small jobs, maybe as a stylist, or prostituting themselves to get by."

Within PR Pride's crowd, trans attendees have a significant impact--their presence is not only visible, but needed, respected and celebrated. One woman wears a blue bodysuit with the trans flag hanging from her arms like angel wings. Balancing a cigarette on her lips and a tiara on her head, she twirls wildly in circles, letting the blue, pink and white fabric fly freely around her body. Photographers crowd around and friends cheer her on. Hours into the parade, I see her again further down Ashford, but now her breasts are out completely--two symbols of her womanhood and public pride. She's still smiling and onlookers still applauding.

"In a small way, we're educating our communities," Torres says, recognizing the recent rise in trans awareness throughout PR. "They are empowering themselves and our LGBTQ organizations are focused on that--on allowing people to recognize who they really are. We're fighting for their rights and collectively raising our voices to say, 'Hello, I'm here.'"

And while this impressive, expansive parade seemed impossible to ignore, I was promptly reminded why such a colorful, outlandish display is still needed when a man casually asked me on my way back from the march, "So, what's everyone celebrating, today?" Armed with a neck full of rainbow-colored beads that were gifted by a stranger along Ashford, I took advantage of the opportunity to effectively raise our voice: "Pride," I said with a smile and full eye contact, remembering the boy from earlier who'd been conditioned to hide his sexuality. "LGBTQ Pride."

Photography: Jo Cosme