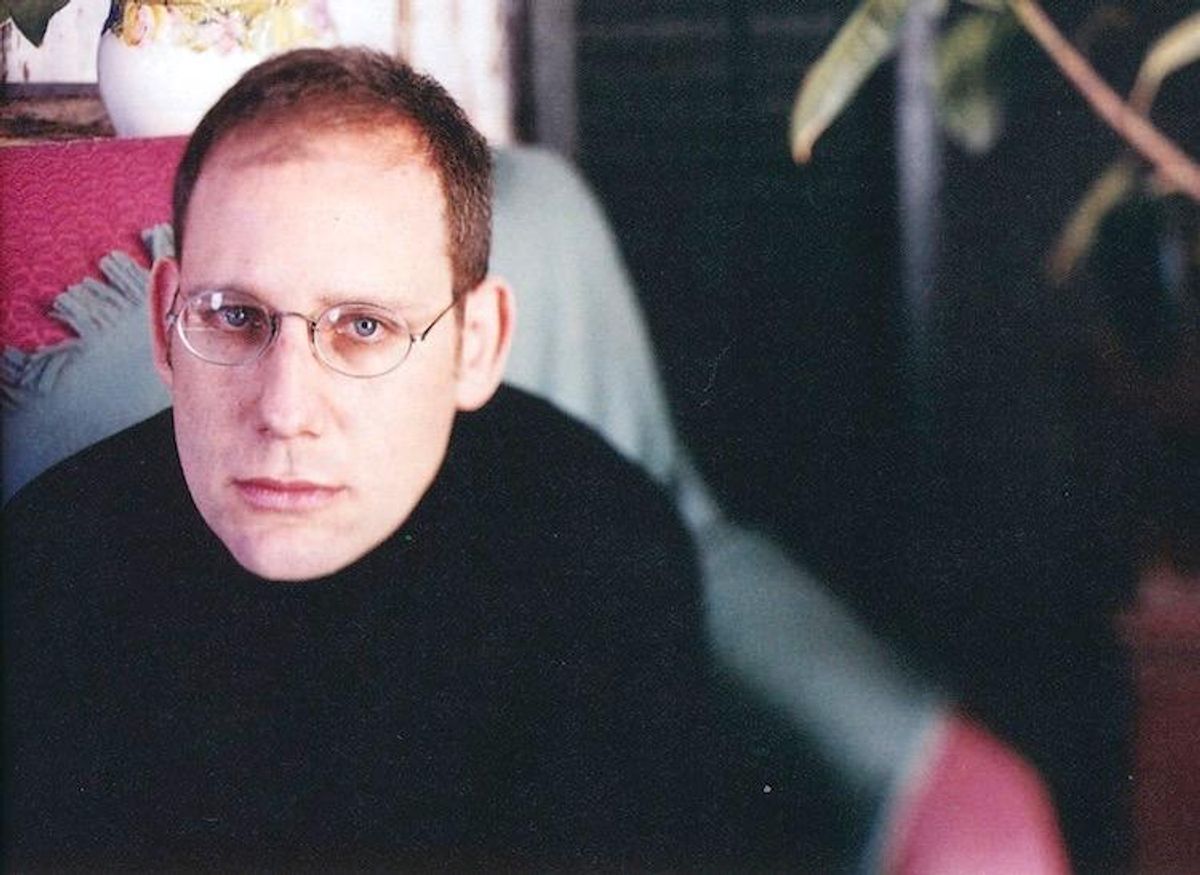

This article originally appeared in the April 1997 issue of OUT.

Some people think David Leavitt has a sex problem--not personally, but as a writer of fiction about gay men. Since the 1984 publication of his acclaimed short story collection Family Dancing, gay critics and readers alike have complained that Leavitt is unqilling or unable to deal with gay male sexuality. His stories and novels seem deeply rooted in a nice, upper-middle-class world of mothers, childhood innocence, and clean white jockey shorts. Novelist and critic Felice Picano once went so far as to claim that Leavitt wrote "as though he didn't have a penis."

Leavitt's new collection of three novellas, Arkansas, published by Houghton Mifflin in April, should change all that. "The Wooden Anniversary" is an E.M. Forster-esque erotic romp in Tuscany told as a Woody Allen comedy of mis-manners; "Saturn Street" portrays a blocked writer who delivers lunch to and falls in lust with a homebound man with AIDS. In both stories, sexual desire fuels the plot and theme. But this is nothing compared with "The Term Paper Artist," in which a novelist named David Leavitt writes term papers for cute straight male undergraduates in exchange for sex. The story was killed from the April Esquite, reportedly for its sexual content. Writing without a penis? I don't think so.

"I don't understand how I got this reputation for being hostile to sex in my work, claims Leavitt today. "I've written about sex. While England Sleeps was about a sexually obsessive affair. The Lost Language of Cranes had lots of sex; it even had a scene were Philip, the main character, shoots his come across the room and it lands, sizzling, on a radiator. I have not shied away from exploring gay sexuality."

So how did Leavitt get this serious image problem as the goody-two-shoes of homo fiction? "[It's] a response to how I presented myself to the world," says Leavitt, now 35. "A clean-cut good boy, happy and monogamous with my lover in East Hampton in our cute little country house with our cute little dog. Like many men of my generation, the open sexuality of gay life horrified me." To a gay literary world predicated, to a large degree, upon celebrating sexual extravagance, this attitude seemed, well, like Attitude.

It's hard not to see some envy at work here too. While older writers like Andrew Holleran, Edmund White, and Larry Kramer had, by the late '70s, already published openly gay material with mainstream presses, it was the wunderkind Leavitt who garnered the much-desired critical accolades and crossover audience. Leavitt became a publishing-world anomaly: a gay writer who found a sustained heterosexual readership.

In the late '80s and early '90s, Leavitt kept writing: His first novel, The Lost Language of Cranes, came out in 1986 (it was later made into a film by the BBC); another novel, Equal Affections, in 1989; a short story collection, A Place I've Never Been, appeared in 1990; the novel While England Sleeps, in 1993. Then Leavitt's seemingly secure career crashed. A devastating four-year block prevented him from writing. The crisis was no doubt exacerbated by British poet Sir Stephen Spender, who waged a high visible public-relations war and filed a lawsuit claiming that Leavitt had illegally appropriated his life as the basis of While England Sleeps. The scandal brought a deluge of negative publicity, the novel was withdrawn and reissued in a "revised" paperback edition, and Leavitt changed publishers. (Spender died in 1995). Out of this professional and personal nightmare comes Arkansas, Leavitt's first published fiction in four years.

The new David Leavitt--having shed the old skin of reputation and genteel respectability--seems less conflicted as a gay man and more assured as a writer. One of the themes of "The Term Paper Artist" is the disjunction between writing for pleasure and writing for material reward. For Leavitt, now at work on a new novel, The Page Turner, the act of writing now produces pleasure in and of itself. And, as in the story, are there material sexual benefits as well? Leavitt laughs. "Did I do it to get laud? I love the idea that if someone liked a story they might go to bed with me."